Dreams and Nightmares

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BATMAN Vs SUPERMAN What Would Superman Drive, What Should Batman Drive and Where Could Wonder Woman Store Her Outfit?

WIN A PULSAR BRUCE WAYNE’S JEEP WATCH PEUGEOT ADD FUEL OFFERS WORTH DUCHESS OF CAMBRIDGE PLAYS TENNIS £145 SHORTLISTED FOR NEWSPRESS MAGAZINE OF THE YEAR BATMAN vs SUPERMAN What would Superman drive, what should Batman drive and where could Wonder Woman store her outfit? Your magazine featuring the stars, their cars and more... freecarmag.co.uk 1 FUELLED BY FUN This ISSUEweek 30 / 2016 Batman vs Superman: Dawn of Justice. We don’t understand why there are a couple of superheroes slugging it out like a wrestling bout, with Wonder Woman watching disapprovingly. However, we are looking forward to making sense of it all very soon at the local multiplex. We’ve got a superhero of our own Free Car Mag, or possibly Margaret, but we are too frightened to call her that. Well she’s more than qualified to tell other superheroes and even super villains what to drive. There is still time to win yourself a brilliant Pulsar watch. All you have to do is sign up to get notification of the latest issue. If you have already signed up, then you are already in with a chance. Tell all your friends and family, because we don’t spam you with nonsense, or pass your details on. We are good like that. 4 News Events Celebs – Made in Chelsea We are also doing very well at the moment. Shortlisted as and Duchess of Cambridge Consumer Magazine and Editor of the Year in the Newspress 6 Batman vs Superman Awards after only being around for a year, it has taken a real 8 Supercars for Superheroes superhuman effort I can tell you. -

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text

JUSTICE LEAGUE (NEW 52) CHARACTER CARDS Original Text ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) PRINTING INSTRUCTIONS 1. From Adobe® Reader® or Adobe® Acrobat® open the print dialog box (File>Print or Ctrl/Cmd+P). 2. Click on Properties and set your Page Orientation to Landscape (11 x 8.5). 3. Under Print Range>Pages input the pages you would like to print. (See Table of Contents) 4. Under Page Handling>Page Scaling select Multiple pages per sheet. 5. Under Page Handling>Pages per sheet select Custom and enter 2 by 2. 6. If you want a crisp black border around each card as a cutting guide, click the checkbox next to Print page border. 7. Click OK. ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) TABLE OF CONTENTS Aquaman, 8 Wonder Woman, 6 Batman, 5 Zatanna, 17 Cyborg, 9 Deadman, 16 Deathstroke, 23 Enchantress, 19 Firestorm (Jason Rusch), 13 Firestorm (Ronnie Raymond), 12 The Flash, 20 Fury, 24 Green Arrow, 10 Green Lantern, 7 Hawkman, 14 John Constantine, 22 Madame Xanadu, 21 Mera, 11 Mindwarp, 18 Shade the Changing Man, 15 Superman, 4 ©2012 WizKids/NECA LLC. TM & © 2012 DC Comics (s12) 001 DC COMICS SUPERMAN Justice League, Kryptonian, Metropolis, Reporter FROM THE PLANET KRYPTON (Impervious) EMPOWERED BY EARTH’S YELLOW SUN FASTER THAN A SPEEDING BULLET (Charge) (Invulnerability) TO FIGHT FOR TRUTH, JUSTICE AND THE ABLE TO LEAP TALL BUILDINGS (Hypersonic Speed) AMERICAN WAY (Close Combat Expert) MORE POWERFUL THAN A LOCOMOTIVE (Super Strength) Gale-Force Breath Superman can use Force Blast. When he does, he may target an adjacent character and up to two characters that are adjacent to that character. -

Gang War Erupts in Combat Zone

WEATHER & GOSSIP OPINION TECH LIFESTYLES ENTERTAINMENT BUSINESS WORLD NEWS HAZARDS Gang War Erupts in Combat Zone By jericho hunt • Night City • 2 Hours Ago Earlier today, the northern sector of the Combat Zone was body conversions and heavily augmented individuals thrust into chaos as tensions between the Iron Sights and either on the edge of or in the grip of cyberpsychosis, the Red Chrome Legion exploded into a full-scale con- lost influence and territory during the Time of the Red. It flict. Bullets flew and rippers sliced as these two violent wasn’t until a recently that the Iron Sights began to see gangs released months of pent up hostility on each other a rise in membership once again. This increase in their and any unfortunate Night City resident that wandered ranks was initially attributed to individuals suffering into their bloody feud. NCPD officers are already on from cyberpsychosis who joined their ranks after fail- the scene attempting to quell this senseless violence but ing to reincorporate into society. But recently, intrepid the sighting of multiple full-body conversions in the fray reporter Jericho Hunt unearthed a discovery that will has necessitated the involvement of C-SWAT. No doubt shock the city and most definitely sheds light on this cur- this conflict will boil over beyond the Combat Zone as rent massacre. Undercover, at a Nomad operated train it escalates. station on the outskirts of Night City, Hunt witnessed a handoff between known Iron Sights affiliates and a mys- But what could have caused this bloodbath? Could there terious cabal of men in black suits. -

Download the Full Dc Future State Checklist!

Store info: FILL OUT THIS INTERACTIVE CHECKLIST AND RETURN TO YOUR RETAILER TO MAKE SURE YOU DON’T MISS AN ISSUE OF DC: FUTURE STATE! (Tuesday availability at participating stores) DC: FUTURE STATE TITLES DC: FUTURE STATE TITLES COMING JANUARY 2021 COMING FEBRUARY AND MARCH 2021 M V M = Main V = Variant M V M = Main V = Variant Check with your retailer for variant cover details. Check with your retailer for variant cover details. Available Tuesday, January 5, 2021 Available Tuesday, February 2, 2021 _ _ Future State: The Next Batman #1 (of 4) _ _ Future State: The Next Batman #3 (of 4) _ _ Future State: The Flash #1 (of 2) _ _ Future State: The Flash #2 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Harley Quinn #1 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Harley Quinn #2 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Superman of Metropolis #1 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Superman of Metropolis #2 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Swamp Thing #1 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Swamp Thing #2 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Wonder Woman #1 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Wonder Woman #2 (of 2) Available Tuesday, January 12, 2021 Available Tuesday, February 9, 2021 _ _ Future State: Dark Detective #1 (of 4) _ _ Future State: Dark Detective #3 (of 4) _ _ Future State: Green Lantern #1 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Green Lantern #2 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Justice League #1 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Justice League #2 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Kara Zor-El, Superwoman #1 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Kara Zor-El, Superwoman #2 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Robin Eternal #1 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Robin Eternal #2 (of 2) _ _ Future State: Superman/Wonder -

Aliens of Marvel Universe

Index DEM's Foreword: 2 GUNA 42 RIGELLIANS 26 AJM’s Foreword: 2 HERMS 42 R'MALK'I 26 TO THE STARS: 4 HIBERS 16 ROCLITES 26 Building a Starship: 5 HORUSIANS 17 R'ZAHNIANS 27 The Milky Way Galaxy: 8 HUJAH 17 SAGITTARIANS 27 The Races of the Milky Way: 9 INTERDITES 17 SARKS 27 The Andromeda Galaxy: 35 JUDANS 17 Saurids 47 Races of the Skrull Empire: 36 KALLUSIANS 39 sidri 47 Races Opposing the Skrulls: 39 KAMADO 18 SIRIANS 27 Neutral/Noncombatant Races: 41 KAWA 42 SIRIS 28 Races from Other Galaxies 45 KLKLX 18 SIRUSITES 28 Reference points on the net 50 KODABAKS 18 SKRULLS 36 AAKON 9 Korbinites 45 SLIGS 28 A'ASKAVARII 9 KOSMOSIANS 18 S'MGGANI 28 ACHERNONIANS 9 KRONANS 19 SNEEPERS 29 A-CHILTARIANS 9 KRYLORIANS 43 SOLONS 29 ALPHA CENTAURIANS 10 KT'KN 19 SSSTH 29 ARCTURANS 10 KYMELLIANS 19 stenth 29 ASTRANS 10 LANDLAKS 20 STONIANS 30 AUTOCRONS 11 LAXIDAZIANS 20 TAURIANS 30 axi-tun 45 LEM 20 technarchy 30 BA-BANI 11 LEVIANS 20 TEKTONS 38 BADOON 11 LUMINA 21 THUVRIANS 31 BETANS 11 MAKLUANS 21 TRIBBITES 31 CENTAURIANS 12 MANDOS 43 tribunals 48 CENTURII 12 MEGANS 21 TSILN 31 CIEGRIMITES 41 MEKKANS 21 tsyrani 48 CHR’YLITES 45 mephitisoids 46 UL'LULA'NS 32 CLAVIANS 12 m'ndavians 22 VEGANS 32 CONTRAXIANS 12 MOBIANS 43 vorms 49 COURGA 13 MORANI 36 VRELLNEXIANS 32 DAKKAMITES 13 MYNDAI 22 WILAMEANIS 40 DEONISTS 13 nanda 22 WOBBS 44 DIRE WRAITHS 39 NYMENIANS 44 XANDARIANS 40 DRUFFS 41 OVOIDS 23 XANTAREANS 33 ELAN 13 PEGASUSIANS 23 XANTHA 33 ENTEMEN 14 PHANTOMS 23 Xartans 49 ERGONS 14 PHERAGOTS 44 XERONIANS 33 FLB'DBI 14 plodex 46 XIXIX 33 FOMALHAUTI 14 POPPUPIANS 24 YIRBEK 38 FONABI 15 PROCYONITES 24 YRDS 49 FORTESQUIANS 15 QUEEGA 36 ZENN-LAVIANS 34 FROMA 15 QUISTS 24 Z'NOX 38 GEGKU 39 QUONS 25 ZN'RX (Snarks) 34 GLX 16 rajaks 47 ZUNDAMITES 34 GRAMOSIANS 16 REPTOIDS 25 Races Reference Table 51 GRUNDS 16 Rhunians 25 Blank Alien Race Sheet 54 1 The Universe of Marvel: Spacecraft and Aliens for the Marvel Super Heroes Game By David Edward Martin & Andrew James McFayden With help by TY_STATES , Aunt P and the crowd from www.classicmarvel.com . -

Is There a Doctor at the Beach ?

l) BEAUTE 1l,y a un homme derriere les peaux radieuses des habituees du tapis rouge. Rencontre aJ Vew York avec le Dr Colbert dermatologue de renom etfidele de Saint-BarthJ dont beaucoup revent dJavoir fa ligne directe. There is a man behind the glowing complexions of red carpet stars. In New Yor( we make an appointment with acclaimed dermatologist and St Barth regular Dr. Colbert, whom many dream of having on speed dial. TEXTE KARE ROUACH IS THERE A DOCTOR AT THE BEACH ? lateau de tournage, casting creur de Manhattan. "Mes patients doivent - Is this a film set, a model casting, or a de defile de mode, ou centre rester naturels, simplement une meilleure doctor's office? It can all get a bit confusing, medical? Dans le cabinet du version d 'eux-m emes." Le fameux soin but pleasantly so. In Dr. Colbert's Fifth Ave Dr Colbert, sur Ia s• Avenue, "Triad", qui lui vaut sa notoriete, est un nue office, you could easily brush shoulders on peut facilement croiser traitement laser specialise, en 30 minutes with Karen Elson in the elevator, Naomi KarPen Elson dans l'ascenseur, Naomi chrono, qui commence par un lissage tres \1\'atts in the waiting room, or Alessandra Watts en salle d'attente ou Alessandra Ieger, puis un laser tonifiant, et enfin une Ambrosio leaning on the reception desk, Ambrosio accoudee au comptoir de l'ac exfoliation aux acides de fleurs. Dans son all of them there to undergo the signature cueil, toutes venues abuser du soin signa premier livre, Th e High School Reunion "Triad" treatment of this skincare star, or ture de ce dermato-star, le "Triad", ou bien Diet, Dr Colbert demontre le lien direct to covertly beat the signs of aging (well, se rajeunir incognito (enfin presque). -

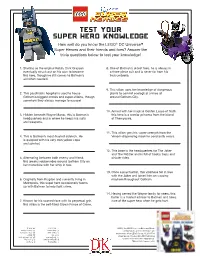

Test Your Super Hero Knowledge

Test Your Super Hero Knowledge How well do you know the LEGO® DC Universe™ Super Heroes and their friends and foes? Answer the trivia questions below to test your knowledge! 1. Starting as the original Robin, Dick Grayson 8. One of Batman’s oldest foes, he is always in eventually struck out on his own to become a three-piece suit and is never far from his this hero, though he still comes to Batman’s trick umbrella. aid when needed! 9. This villain uses her knowledge of dangerous 2. This psychiatric hospital is used to house plants to commit ecological crimes all Gotham’s biggest crooks and super-villains, though around Gotham City. somehow they always manage to escape! 10. Armed with her magical Golden Lasso of Truth, 3. Hidden beneath Wayne Manor, this is Batman’s this hero is a warrior princess from the island headquarters and is where he keeps his suits of Themyscira. and weapons. 11. This villain gets his super-strength from the 4. This is Batman’s most-trusted sidekick. He Venom-dispensing mask he constantly wears. is quipped with his very own yellow cape and symbol. 12. This base is the headquarters for The Joker and The Riddler and is full of booby traps and 5. Alternating between both enemy and friend, sinister rides. this jewelry robber rides around Gotham City on her motorbike with her whip in tow. 13. Once a psychiatrist, this villainess fell in love with the Joker and joined him on causing 6. Originally from Krypton and currently living in mayhem throughout Gotham. -

Fantastic Four Compendium

MA4 6889 Advanced Game Official Accessory The FANTASTIC FOUR™ Compendium by David E. Martin All Marvel characters and the distinctive likenesses thereof The names of characters used herein are fictitious and do are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. not refer to any person living or dead. Any descriptions MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS including similarities to persons living or dead are merely co- are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. incidental. PRODUCTS OF YOUR IMAGINATION and the ©Copyright 1987 Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. All TSR logo are trademarks owned by TSR, Inc. Game Design Rights Reserved. Printed in USA. PDF version 1.0, 2000. ©1987 TSR, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Table of Contents Introduction . 2 A Brief History of the FANTASTIC FOUR . 2 The Fantastic Four . 3 Friends of the FF. 11 Races and Organizations . 25 Fiends and Foes . 38 Travel Guide . 76 Vehicles . 93 “From The Beginning Comes the End!” — A Fantastic Four Adventure . 96 Index. 102 This book is protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America. Any reproduction or other unauthorized use of the material or artwork contained herein is prohibited without the express written consent of TSR, Inc., and Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. Distributed to the book trade in the United States by Random House, Inc., and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Ltd. Distributed to the toy and hobby trade by regional distributors. All characters appearing in this gamebook and the distinctive likenesses thereof are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. MARVEL SUPER HEROES and MARVEL SUPER VILLAINS are trademarks of the Marvel Entertainment Group, Inc. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Mapping Black Ash Dominated Stands Using Geospatial and Forest Inventory Data in Northern Minnesota, USA Peder S

892 ARTICLE Mapping black ash dominated stands using geospatial and forest inventory data in northern Minnesota, USA Peder S. Engelstad, Michael J. Falkowski, Anthony W. D’Amato, Robert A. Slesak, Brian J. Palik, Grant M. Domke, and Matthew B. Russell Abstract: Emerald ash borer (EAB; Agrilus planipennis Fairmaire, 1888) has been a persistent disturbance for ash forests in the United States since 2002. Of particular concern is the impact that EAB will have on the ecosystem functioning of wetlands dominated by black ash (Fraxinus nigra Marsh.). In preparation, forest managers need reliable and complete maps of black ash dominated stands. Traditionally, forest survey data from the United States Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) Program have provided rigorous measures of tree species at large spatial extents but are limited when providing estimates for smaller management units (e.g., stands). Fortunately, geospatial data can extend forest survey information by generating predictions of forest attributes at scales finer than those of the FIA sampling grid. In this study, geospatial data were integrated with FIA data in a randomForest model to estimate and map black ash dominated stands in northern Minnesota in the United States. The model produced low error rates (overall error = 14.5%; area under the curve (AUC) = 0.92) and was strongly informed by predictors from soil saturation and phenology. These results improve upon FIA-based spatial estimates at national extents by providing forest managers with accurate, fine-scale maps (30 m spatial resolution) of black ash stand dominance that could ultimately support landscape-level EAB risk and vulnerability assessments. Key words: compound topographic index (CTI), remote sensing, black ash, emerald ash borer, forest inventory. -

Translating Expertise Across Work Contexts: U.S. Puppeteers Move

ASRXXX10.1177/0003122420987199American Sociological ReviewAnteby and Holm 987199research-article2021 American Sociological Review 2021, Vol. 86(2) 310 –340 Translating Expertise across © American Sociological Association 2021 https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122420987199DOI: 10.1177/0003122420987199 Work Contexts: U.S. Puppeteers journals.sagepub.com/home/asr Move from Stage to Screen Michel Antebya and Audrey L. Holma Abstract Expertise is a key currency in today’s knowledge economy. Yet as experts increasingly move across work contexts, how expertise translates across contexts is less well understood. Here, we examine how a shift in context—which reorders the relative attention experts pay to distinct types of audiences—redefines what it means to be an expert. Our study’s setting is an established expertise in the creative industry: puppet manipulation. Through an examination of U.S. puppeteers’ move from stage to screen (i.e., film and television), we show that, although the two settings call on mostly similar techniques, puppeteers on stage ground their claims to expertise in a dialogue with spectators and view expertise as achieving believability; by contrast, puppeteers on screen invoke the need to deliver on cue when dealing with producers, directors, and co-workers and view expertise as achieving task mastery. When moving between stage and screen, puppeteers therefore prioritize the needs of certain audiences over others’ and gradually reshape their own views of expertise. Our findings embed the nature of expertise in experts’ ordering of types of audiences to attend to and provide insights for explaining how expertise can shift and become co-opted by workplaces. Keywords expertise, audiences, puppetry, film and television Expertise has become a fundamental currency of cases (Abbott 1988:8). -

Cineworld.Pdf

Cineworld Unlimited Survey * 1. What is your gender? Female Male * 2. What Region do you live in? Scotland North East North West East Midlands West Midlands Wales East Anglia South East South West Ireland * 3. How many times have you been to the cinema in the past three months? 03 times 45 times 68 times 9+ times * 4. What Genre of films have you seen most in the last three months? Drama Romance Comedy Thriller SciFi Non English Language Animated Musical Family * 5. Who did you go to the cinema with most over the last three months? Partner/Husband or Wife Friends Children Date By yourself * 6. Who do you think is the sexiest actress of all time? Angeline Jolie Scarlett Johansson Natalie Portman Marilyn Monroe Grace Kelly Cameron Diaz Emma Stone Brigitte Bardot Halle Berry Julia Roberts * 7. Who to you think it the sexiest actress from the upcoming films this summer? Cary Mulligan The Great Gatsby Amy Adams Man of Steel Tao Okamoto The Wolverine Kristen Bell Stuck In Love Vera Farmiga The Conjuring * 8. Which of these superhero characters would you most like to date in real life? Tobey Maguire Spiderman Christian Bale Batman Robert Downey Jnr Iron Man Henry Cavil Superman Chris Evans Captain America Nicholas Cage Big Daddy (Kick Ass) Chris Hemsworth Thor Mark Ruffalo The Hulk Hugh Jackman Wolverine * 9. If you could play the part of a superheroes' love interest which character would you choose? Lois Lane Superman Pepper Pots Iron Man Jane Foster Thor Rachel Dawes Batman Mary Jane Spiderman Betty Ross the Hulk Penny Carter Captain America * 10.