Journal of Public Interest Communications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barring Immoral Speech in Patent and Copyright

SMU Law Review Volume 74 Issue 1 Article 5 2021 Barring Immoral Speech in Patent and Copyright Ned Snow University of South Carolina School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Part of the First Amendment Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Ned Snow, Barring Immoral Speech in Patent and Copyright, 74 SMU L. REV. 163 (2021) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol74/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. BARRING IMMORAL SPEECH IN PATENT AND COPYRIGHT Ned Snow* ABSTRACT In the past three years, the Supreme Court has twice ruled that Con- gress’s moral bars to trademark protection violate the First Amendment. Those rulings raise a simple question in other areas of intellectual property. Does the First Amendment preclude Congress from denying patent or cop- yright protection based on a moral reason? Congress, for instance, might deny patent protection for inventions directed toward the consumption of marijuana. Inventors would accordingly choose not to disclose knowledge about those inventions to the public, and the denial would chill their speech. Similarly, Congress would chill speech if it denied copyright pro- tection for moral reasons. A copyright bar to statues of the Confederacy, for instance, would deter artists from speaking such content. Hence, through patent and copyright, Congress might seek to influence speech in accord with its moral viewpoint. -

Mass Shooters' Understanding of Law, Politics, and Crime by Tifenn

Extremist Manifestos: Mass Shooters’ Understanding of Law, Politics, and Crime by Tifenn Drouaud B.A. in Criminal Justice & Political Science, May 2018, The George Washington University A Thesis submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of the George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Arts August 31, 2020 Thesis directed by Fran Buntman Assistant Professor of Sociology © Copyright 2020 by Tifenn Drouaud All rights reserved ii Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank Professor Fran Buntman for igniting my passion in this field and for her continued support, guidance, and encouragement throughout the many stages of this project. Her ability to challenge me has yielded my best ideas. The author also wishes to thank Professor Xolela Mangcu of George Washington University for providing his unique perspective and feedback. Additional thanks are given to the author’s parents, family, and friends for their relentless unwavering love, patience, and praise. Their support has never waned and without them, none of my accomplishments are possible. iii Abstract Extremist Manifestos: Mass Shooters’ Understanding of Law, Politics, and Crime A subset of mass shooters writes manifestos which outline the rationale for their intended violence. Most scholarly assessments focused on the psychological perspective of the shooters (Hamlett 2017; Knoll 2012; Bondü & Schneithauer 2015). Instead, this thesis considers the shooters’ socio-legal imagination as offered in their manifestos, focusing on their understanding and construal of crime, law, and politics. Most of these shooters portray their violence as a form of justice in an unjust world. -

Active Shooters Watch Movie Online

Active Shooters Watch Movie Online Active Shooters Watch Movie Online 1 / 3 2 / 3 Mass shooting contagion theory is the studied nature and effect of media coverage of mass ... The Sandy Hook shooter, Adam Lanza, was active in online commentary about U.S. mass shootings, posting in ... primary inspiration for his mass homicide included Columbine, Aurora Movie Theatre and Virginia Tech shooters.. This is the FBI's one-stop shopping webpage for information pertaining to active shooting incidents. The Bureau continues its commitment to working with its .... Discover ideas about Tv Series Online. Watch Active Shooters full hd online Directed by Mike Reeping. With Thomas Reeping, Jesse-Lee Lafferty, Nick .... Active Shooter: America Under Fire. All Episodes Now Available. Watch Now. STREAM SHOWTIME NOW. try it now for free .... Showtime Networks Inc. Purchase rights: Stream instantly Details. Format: Prime Video (streaming online video).. A hard-hitting examination of mass shootings in the US, beginning with the 2012 incident at a movie theatre in Aurora, Colorado. Episode 1. Episode 2.. A Killer on Floor 32 takes you inside the deadliest mass shooting in modern American history using never .... Military and FBI issues urgent warning ahead of 'Joker' releaseThe U.S. military has alerted service members there could be potential violence at .... Now living a quiet life, ex-Marine sniper Bob Lee Swagger agrees to help his former commander prevent the assassination of the U.S. president. Watch Exfil.. (The film uses the broader definition of mass shooting, which sets the ... The 12-minute short was released online Tuesday by Field of Vision, ... -

Callitfemicide: Understanding Gender-Related Killings of Women and Girls in Canada 2019 CAN Femicide CAN.Femicide [email protected] Femicideincanada.Ca

#CallItFemicide Understanding gender-related killings of women and girls in Canada 2019 https://femicideincanada.ca CAN_Femicide CAN.Femicide [email protected] femicideincanada.ca Table of Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................... 4 Why is it important to identify gender-related motives and indicators in femicide? ......................................... 43 Foreword ......................................................................... 5 What is a gender-related motive or indicator for Dedication ....................................................................... 6 femicide? ..................................................................... 45 Executive Summary .......................................................... 7 GRMI #1: Committed previous physical, psychological, Introduction ..................................................................... 9 and/or sexual violence ................................................ 47 The Canadian Femicide Observatory for Justice and GRMI #2: Coercive-controlling behaviours .................. 47 Accountability .............................................................. 11 GRMI #3: Separation (or in the process of separation) 48 Structure of this report ................................................ 12 GRMI #4: Victim declined to establish or re-establish a Section I: The Growing Global Fem[in]icide Movement .... 15 relationship .................................................................. 50 Latin America .............................................................. -

Characteristics of Fame-Seeking Individuals Who Completed Or Attempted Mass Murder in the United States Angelica Wills Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2019 Characteristics of Fame-Seeking Individuals Who Completed or Attempted Mass Murder in the United States Angelica Wills Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Personality and Social Contexts Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Social and Behavioral Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Angelica Wills has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Eric Hickey, Committee Chairperson, Psychology Faculty Dr. Christopher Bass, Committee Member, Psychology Faculty Dr. John Schmidt, University Reviewer, Psychology Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2019 Abstract Characteristics of Fame-Seeking Individuals Who Completed or Attempted Mass Murder in the United States by Angelica Wills MS, Walden University, 2016 BA, Stockton University, 2008 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Clinical Psychology Walden University June 2019 Abstract Previous researchers have found mass murderers characterized as loners, victims of bullying, goths, and individuals who had a psychotic break. A gap in the literature that remained concerned the motive and mindset of mass murderers before their attack, particularly those who seek fame, and why they are motivated by such violent intentions. -

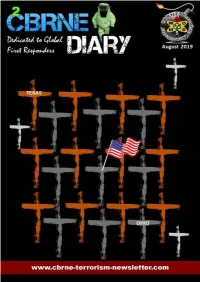

AUG 2019 Part A.Pdf

1 C2BRNE DIARY – August 2019 www.cbrne-terrorism-newsletter.com 2 C2BRNE DIARY – August 2019 C2BRNE DIARY– 2019© August 2019 Website: www.cbrne-terrorism-newsletter.com Editor-in-Chief BrigGEN (ret) Ioannis Galatas MD, MA, MC (Army) PhD cand Consultant in Allergy & Clinical Immunology Medical/Hospital CBRNE Planner & Instructor Senior Asymmetric Threats Analyst Manager, CBRN Knowledge Center @ International CBRNE Institute (BE) Athens, Greece Contact e-mail: [email protected] Editorial Team ⚫ Bellanca Giada, MD, MSc (Italy) ⚫ Hopmeier Michael, BSc/MSc MechEngin (USA) ⚫ Kiourktsoglou George, BSc, Dipl, MSc, MBA, PhD (cand) (UK) ⚫ Photiou Steve, MD, MSc EmDisaster (Italy) ⚫ Tarlow Peter, PhD Sociol (USA) Advertise with us! CBRNE-Terrorism Newsletter is published on-line monthly and distributed free of charge. ⚫ Sponsors of the International CBRNE Institute can advertise for free. ⚫ CBRNE related companies can advertise for free. PUBLISHER Mendor Editions S.A. 3 Selinountos Street 14231 Nea Ionia Athens, Greece Tel: +30 210 2723094/-5 Fax: +30 210 2723698 Contact e-mail: Valia Kalantzi [email protected] DISCLAIMER: The CBRNE-Terrorism Newsletter® is a free online publication for the fellow civilian/military First Responders worldwide. The Newsletter is a collection of papers/articles related to the stated thematology. Relevant sources/authors are included and all info provided herein is from open Internet sources. Opinions and comments from the Editor, the Editorial group or the authors publishing in the Newsletter do not necessarily represent those of the Publisher or the International CBRNE Institute. www.cbrne-terrorism-newsletter.com 3 C2BRNE DIARY – August 2019 C2BRNE DIARY is: 1. Read by First Responders in more than 80 countries around the globe; 2. -

Homicide by Necessity

119-186 COHAN.DOC 12/26/2006 11:34:38 AM Homicide by Necessity John Alan Cohan* INTRODUCTION...........................................................................120 I. ELEMENTS OF THE NECESSITY DEFENSE ................................123 II. HISTORICAL EXAMPLES OF HOMICIDE BY NECESSITY............127 III. HOMICIDE BY NECESSITY: THE MINORITY VIEW ..................133 IV. THE NAZI HOLOCAUST CASE ................................................137 V. STATUTORY LAW ADDRESSING HOMICIDE BY NECESSITY ......139 VI. THE LANDMARK HOMICIDE BY NECESSITY CASES................141 A. United States v. Holmes.............................................141 B. Regina v. Dudley & Stephens ....................................160 VII. THE SPELUNCEAN EXPLORERS ...........................................170 VIII. INNOCENT SHIELDS OF THREATS.......................................177 A. The Choice of Evils Prong..........................................179 B. The Imminence Prong................................................181 C. The Causal Nexus Prong ...........................................181 D. The Legal Way Out Prong.........................................182 E. The Preemption Prong...............................................182 F. The Clean Hands Prong.............................................182 IX. HOMICIDE BY NECESSITY: THE FUTURE...............................182 CONCLUSION ..............................................................................183 * J.D., Loyola Law School, magna cum laude, 1972; B.A., University of Southern -

Using Genre Theory to Reduce Mass Shootings

College of DuPage DigitalCommons@COD Student Scholarship English 1-31-2020 Using Genre Theory to Reduce Mass Shootings Meghna Israni College of DuPage Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.cod.edu/englishpub_student_pubs Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Israni, Meghna, "Using Genre Theory to Reduce Mass Shootings" (2020). Student Scholarship. 1. https://dc.cod.edu/englishpub_student_pubs/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at DigitalCommons@COD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@COD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Using Genre Theory to Reduce Mass Shootings Meghna Israni | College of DuPage “Suicide contagion” is a well-established phenomenon in which highly publicized suicides are followed by a spike in the general suicide rate. In recent years, scholars have proposed a similar media contagion effect in mass shootings, a claim that’s supported by a growing body of statistical and sociological evi- dence. The fact that increased media coverage is linked to an increase in the probability of another mass shooting suggests that news media exercise some power over mass shootings. This paper, drawing attention to the “genres” within mass shootings, explores how news media can rewrite these narratives in order to craft a more responsible response. In 1974, sociologist David Phillips noticed a (Towers et al. 7) and that incidents rise in worrying trend in suicides. After each response to increased media coverage (Lee highly publicized suicide, the national sui- 33). Several have noted the significance of cide rate increased. -

The Journal Investigative Reporters & Editors

Backgrounding Investigating Abuse Fact-Checking New tools to boost your research into Two data-driven stories shed light on A step-by-step guide to make your work people and companies abuse behind closed doors bulletproof The Investigative Reporters & Editors Journal FOURTH QUaRTeR 2018 COVERING GUNS CRIME • PUBLIC HEALTH • MASS SHOOTINGS KNOW FIRST. ACT FASTER. Newsrooms around the “If it’s a world use Dataminr to breaking find stories that matter story, nine times out of most and bring them to 10 we see it audiences first. on Dataminr before we see it anywhere else.” Learn more: dataminr.com/news 2 The IRE Journal IRE Journal FOURTH QUARTER 2018 2 Director’s Note Unity after a turbulent year 3 IRE News + Ask IRE Data diaries, fellowships and training news 4 Investigator’s Toolbox Backgrounding people and companies 6 Data Dive REPORTING ON GUNS Shedding light on abuse behind closed doors 8 Show Your Work The ultimate fact- Collected Public health items of checking workflow Guns and dementia 14 a teen deemed a 10 Florida's youngest shooting victims 18 potential Under occupation threat to A Q&A with Valentyna his school. Samar of Ukraine’s BETH Center for Investigative Mass shootings NAKAMURA/ THE Reporting OREGONIAN/ Preventing mass shooting contagion 22 OREGONLIVE 12 Stopping the next school shooter 24 Distributed data Newsrooms team up to The Basics purchase voter data A journalist’s guide to gun terminology 30 36 FOI Files New digital tools for Crime finding data to request Tracing stolen guns across America 33 37 Collected Wisdom Small newsrooms can produce big stories Fourth Quarter 2018 1 DIRECTOR’S NOTE MASTHEAD VOL. -

Jennifer B. Johnston Behavioral Sciences Department Western New Mexico University 1000 College Ave., Silver City, NM 88061 [email protected] (575)538-6303

Jennifer B. Johnston Behavioral Sciences Department Western New Mexico University 1000 College Ave., Silver City, NM 88061 [email protected] (575)538-6303 ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS WNMU Assistant Professor of Psychology 2015-present EDUCATION Ph.D. Psychology, emphasis media, Fielding Graduate University, Santa Barbara, CA 2009-2013 Committee: Karen Dill-Shackleford, Jean-Pierre Isbouts, Erica Scharrer, William Marelich M.A. Counseling, Webster University, Albuquerque, NM 1994-1996 B.S. Psychology, Santa Clara University, Santa Clara, CA 1990-1994 Honors: cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa SCHOLARLY ACTIVITY Publications (bold indicates student collaborator) Johnston, J.B., Joy, A.T., & Marin-Echazarreta, K. (under review). Does parasocial relating to mass shooters increase hostility and encourage acceptance of mass homicide? Media Psychology. Johnston, J.B. (2018). Effects of press coverage on mass shootings. (Federal Commission on School Safety). Washington, D.C.: Department of Education. https://www2.ed.gov/documents/press-releases/201806-fcss-jennifer-johnston.pdf Johnston, J.B. (2014). Early exposure to pornography and later sexual satisfaction: Gender as Moderator. Fielding Monograph, 3, 49-81. Johnston, J.B. (2012). Early exposure to pornography: Indirect and direct effects on sexual satisfaction in adulthood. Doctoral dissertation. Fielding Graduate University, Santa Barbara, CA. Book Chapters Johnston, J.B. & Dill-Shackleford, K.E. (2019). Rape-myth acceptance. In J. Van den Bulck (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of Media Psychology (pp. xx-xx). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley- Blackwell. Johnston, J.B. (2019). What do we know about porn? In S.L. Chemaly (Ed.), GenXXX: Why You Should Talk to Your Kids About Porn (pp. xx-xx). Undetermined publisher. Johnston, J.B. -

Violence and Disorder in the Sede Vacante of Early Modern Rome, 1559-1655

VIOLENCE AND DISORDER IN THE SEDE VACANTE OF EARLY MODERN ROME, 1559-1655 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By John M. Hunt, M. A. ***** The Ohio State University 2009 Dissertation Committee Professor Robert C. Davis Professor Noel G. Parker ______________________________ Professor Barbara A. Hanawalt Advisor History Graduate Program Professor Terri Hessler ABSTRACT From the death of every pope until the election of his successor in the early modern era, the entire bureaucratic and judicial apparatus of the state in Rome and the Papal States effectively ceased to function. During this interregnum, known as the sede vacante (literally, “the vacant see”), violence and disorder dramatically increased as the papal government temporarily lost its control over the populace and its monopoly of violence. The College of Cardinals and local civic governments throughout the Papal States, authorities deputized to regulate affairs during sede vacante, failed to quell the upsurge of violence that commenced immediately upon the pope’s death. Contemporary observers and modern scholars have labeled the violence of sede vacante as meaningless and irrational. I argue, rather, that this period of unrest gave Romans and subjects of the Papal States an opportunity to perform actions increasingly forbidden by the centralizing papal government—and thus ultimately to limit the power of the government and prevent the development of the papacy into an absolute monarchy. Acting as individuals or as collectivities, Romans and papal subjects sought revenge against old enemies, attacked hated outsiders, criticized papal policies, and commented on the papal election. -

An Examination of School Shootings and Mental Health: a Comparative Case Study Emily Kaufman

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 3-2018 An Examination of School Shootings and Mental Health: A Comparative Case Study Emily Kaufman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Child Psychology Commons, Counseling Commons, Educational Psychology Commons, Health and Physical Education Commons, and the School Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Kaufman, Emily, "An Examination of School Shootings and Mental Health: A Comparative Case Study" (2018). Honors Theses. 1684. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1684 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. An Examination of School Shootings and Mental Health: A Comparative Case Study By Emily A. Kaufman ********** Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for honors in the Department of Sociology Union College 2018 Abstract KAUFMAN, EMILY. An Examination of School Shootings and Mental Health: A Comparative Case Study. Department of Sociology, March 2018. ADVISOR: Deidre Hill Butler School shootings have become more relevant in our society over the past few decades, yet the debate over the cause of these shootings never seems to reach a conclusion. The current study looks at the connection between mental illness and school shootings, as well as the roles that media, gun control, violence, and masculinity play in the common phenomena. Prior literature has debated over the main causes of school shootings, but many researchers state differing opinions regarding the motivations for perpetrators.