Law Enforcement Perception of Social Media As an Influence in Mass Shootings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

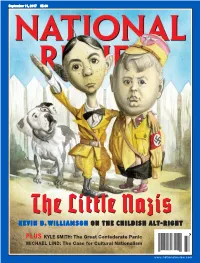

The Little Nazis KE V I N D

20170828 subscribers_cover61404-postal.qxd 8/22/2017 3:17 PM Page 1 September 11, 2017 $5.99 TheThe Little Nazis KE V I N D . W I L L I A M S O N O N T H E C HI L D I S H A L T- R I G H T $5.99 37 PLUS KYLE SMITH: The Great Confederate Panic MICHAEL LIND: The Case for Cultural Nationalism 0 73361 08155 1 www.nationalreview.com base_new_milliken-mar 22.qxd 1/3/2017 5:38 PM Page 1 !!!!!!!! ! !! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !! "e Reagan Ranch Center ! 217 State Street National Headquarters ! 11480 Commerce Park Drive, Santa Barbara, California 93101 ! 888-USA-1776 Sixth Floor ! Reston, Virginia 20191 ! 800-USA-1776 TOC-FINAL_QXP-1127940144.qxp 8/23/2017 2:41 PM Page 1 Contents SEPTEMBER 11, 2017 | VOLUME LXIX, NO. 17 | www.nationalreview.com ON THE COVER Page 22 Lucy Caldwell on Jeff Flake The ‘N’ Word p. 15 Everybody is ten feet tall on the BOOKS, ARTS Internet, and that is why the & MANNERS Internet is where the alt-right really lives, one big online 35 THE DEATH OF FREUD E. Fuller Torrey reviews Freud: group-therapy session The Making of an Illusion, masquerading as a political by Frederick Crews. movement. Kevin D. Williamson 37 ILLUMINATIONS Michael Brendan Dougherty reviews Why Buddhism Is True: The COVER: ROMAN GENN Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment, ARTICLES by Robert Wright. DIVIDED THEY STAND (OR FALL) by Ramesh Ponnuru 38 UNJUST PROSECUTION 12 David Bahnsen reviews The Anti-Trump Republicans are not facing their challenges. -

Spencer Sunshine*

Journal of Social Justice, Vol. 9, 2019 (© 2019) ISSN: 2164-7100 Looking Left at Antisemitism Spencer Sunshine* The question of antisemitism inside of the Left—referred to as “left antisemitism”—is a stubborn and persistent problem. And while the Right exaggerates both its depth and scope, the Left has repeatedly refused to face the issue. It is entangled in scandals about antisemitism at an increasing rate. On the Western Left, some antisemitism manifests in the form of conspiracy theories, but there is also a hegemonic refusal to acknowledge antisemitism’s existence and presence. This, in turn, is part of a larger refusal to deal with Jewish issues in general, or to engage with the Jewish community as a real entity. Debates around left antisemitism have risen in tandem with the spread of anti-Zionism inside of the Left, especially since the Second Intifada. Anti-Zionism is not, by itself, antisemitism. One can call for the Right of Return, as well as dissolving Israel as a Jewish state, without being antisemitic. But there is a Venn diagram between anti- Zionism and antisemitism, and the overlap is both significant and has many shades of grey to it. One of the main reasons the Left can’t acknowledge problems with antisemitism is that Jews persistently trouble categories, and the Left would have to rethink many things—including how it approaches anti- imperialism, nationalism of the oppressed, anti-Zionism, identity politics, populism, conspiracy theories, and critiques of finance capital—if it was to truly struggle with the question. The Left understands that white supremacy isn’t just the Ku Klux Klan and neo-Nazis, but that it is part of the fabric of society, and there is no shortcut to unstitching it. -

2017-2018 Wisconsin Blue Book: Election Results

ELECTION RESULTS County vote for superintendent of public instruction, February 21, 2017 spring primary Tony Evers* Lowell E. Holtz John Humphries Total Adams . 585 264 95 948 Ashland. 893 101 49 1,047 Barron. 1,190 374 172 1,740 Bayfield . 1,457 178 96 1,732 Brown. 8,941 2,920 1,134 13,011 Buffalo . 597 178 66 843 Burnett ���������������������������������������������������������������������������� 393 165 66 625 Calumet . 1,605 594 251 2,452 Chippewa . 1,922 572 242 2,736 Clark. 891 387 166 1,447 Columbia. 2,688 680 299 3,670 Crawford ������������������������������������������������������������������������� 719 130 86 939 Dane . 60,046 4,793 2,677 67,720 Dodge . 2,407 1,606 306 4,325 Door. 1,602 350 133 2,093 Douglas. 2,089 766 809 3,701 Dunn . 1,561 342 147 2,054 Eau Claire. 5,437 912 412 6,783 Florence . 97 52 18 167 Fond du Lac ������������������������������������������������������������������� 3,151 1,726 495 5,388 Forest ������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 241 92 41 375 Grant . 2,056 329 240 2,634 Green ������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 1,888 379 160 2,439 Green Lake. 462 251 95 809 Iowa . 1,989 311 189 2,498 Iron . 344 106 43 494 Jackson . 675 187 91 955 Jefferson ������������������������������������������������������������������������� 3,149 1,544 305 5,016 Juneau . 794 287 110 1,195 Kenosha . 4,443 1,757 526 6,780 Kewaunee ���������������������������������������������������������������������� 619 218 85 923 La Crosse . 5,992 848 632 7,486 Lafayette ������������������������������������������������������������������������� 814 172 105 1,094 Langlade ������������������������������������������������������������������������� 515 201 103 820 Lincoln ���������������������������������������������������������������������������� 843 280 117 1,245 Manitowoc. 2,656 1,405 543 4,616 Marathon. -

Why Is Junk Food So Addictive?

The Z Cal Young MiddleINGER School Spring Term, 2019 Why is Junk Food so Addictive? By Laurel Bonham Have you ever gone to a chip bag just for concentrated salt added to food to enhance flavor. one chip and came back with way more than one? MSG produces a savory but salty taste when You’re not the only one. 53.12% of Americans eat added to food ,which excites your taste buds and 1-3 cans of Pringles in 30 days! That’s over half of stimulates the release of brain chemicals called the people in the U.S.! Most people know that junk neurotransmitters. The pleasant taste of MSG food is well junk. Even people who eat junk food and the release of neurotransmitters are thought aren’t fooled. They know it’s not healthy but what to be the basis for mild levels of addiction. MSG they don’t know is that it has released something makes food salty and it is cheap to make so that called dopamine in their brain. Dopamine is a they can put more of it and it will make people buy chemical that is released in the brain when you more of it because its addictive. MSG is extremely “reward” yourself. You can “reward” yourself by bad for you. Some side effects of MSG are doing pretty much anything. For example when severe headaches, sweating excessively, muscle you go on your phone that is a “reward” for your weakness, and numbness. brain. Eating junk food is just as bad as tobacco is Why do holidays encourage eating for the brain. -

Red River Radio Ascertainment Files October 2017 – December 2017 STORY LOG – Chuck Smith, NEWS PRODUCER, RED RIVER RADIO

Red River Radio Ascertainment Files October 2017 – December 2017 STORY LOG – Chuck Smith, NEWS PRODUCER, RED RIVER RADIO 2498 University of Louisiana System Raises College Grad Goals (1:08) Aired: October 10, 2017 Interview: Jim Henderson, President - University of Louisiana System Type: Interview Wrap 2499 La. Film Prize Wraps 6th Festival Season (3:28) Aired: October 11, 2017 Interview: Gregory Kallenberg, Exec. Dir.-LaFilmPrize, Shreveport, LA Type: Interview Wrap 2500 Many Still Haven't Applied For La. 2016 Flood Recovery Funds (1:53) Aired: October 12, 2017 Interview: Pat Forbes, director for the Louisiana Office of Community Development Type: Interview Wrap 2501 LSUS Pioneer Day Takes Us Back In Time This Saturday (3:28) Aired: October 13, 2017 Interview: Marty Young, Director – Pioneer Heritage Center, LSU-Shreveport Type: Interview Wrap 2502 Share A Story With StoryCorps In Shreveport (2:11) Aired: October 16, 2017 Interview: Morgan Feigalstickles, Site Manager / StoryCorps Type: Interview Wrap 2503 La. Coastal Restoration Projects $50 Billion Over 50 Years (2:15) Aired: Oct 17, 2017 Interview: Johny Bradberry, La. Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority Type: Interview Wrap 2504 Selling Pumpkins To Support Charities in Shreveport-Bossier (2:44) Aired: Oct. 19, 2017 Interview: Janice Boller, Chairman – St. Luke’s Pumpkin Patch Committee Type: Interview Wrap 2505 No Action From Bossier School Board Regarding Student Rights Allegations (1:54) Aired: Oct. 20, 2017 Interview: Charles Roads, South Texas College of Law / Houston, TX Type: Interview Wrap 2506 Caddo Commission Votes For Confederate Monument Removal (1:08) Aired: Oct. 20, 2017 Interview: Lloyd Thompson, President - Caddo Parish NAACP Type: Interview Wrap 2507 National Wildlife Refuge President Visits East Texas Wildlife Refuges (3:26) Aired: Oct 23, 2017 Interview: Geoffrey Haskett, President - National Wildlife Refuge Association Type: Interview Wrap 2508 NW La. -

Charlottesville: One Year Later

Charlottesville: One Year Later Sections 1 Introduction 4 Unite the Right 2 2 The Charlottesville Backlash 5 White Supremacy Continues to Surge 3 Disunity and Division INTRODUCTION On August 11, 2017, the world watched in horror as hundreds of torch-wielding white supremacists descended on the University of Virginia campus, chanting, “Jews will not replace us!” The next day, the streets of Charlottesville exploded in violence, ringing with the racist shouts of th thththththeeee n nnneo-Nazis,eo-Nazis,eo-Nazis,eo-Nazis, Klan KlanKlanKlan m mmmembersembersembersembers an ananandddd alt altaltalt rightrightrightright agitat agitatagitatagitatorsorsorsors wh whwhwhoooo gath gathgathgathererereredededed in ininin an ananan unpr unprunprunprecedentedecedentedecedentedecedented sh shshshowowowow of ofofof unity unityunityunity. Their stated 1 / 9 common cause: To protest the removal of a Confederate statue from a local park. Their true purpose: To show to the world the strength and defiance of the white supremacist movement. The promise of Unite the Right, organized primarily by alt right activist Jason Kessler, brought white supremacists of all stripesstripesstripesstripes t tttogethogethogethogetherererer for forforfor a aaa week weekweekweekenenenendddd of ofofof prprprprotestotestotestotest that thatthatthat quickly quicklyquicklyquickly turn turnturnturnedededed t tttoooo vio viovioviolenlenlenlence,ce,ce,ce, culminating in the brutal murder of anti- racist counter-protester Heather Heyer. The white supremacist mayhem prevented the Saturday rally itself from actually occurring, as local and state police converged on the chaotic scene, urging everyone off the streets and away from the parks. Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe declared a state of emergency and authorities shut down Unite the Right. Despite this, high profile white supremacists like Richard Spencer and David Duke declardeclardeclardeclaredededed Unite UniteUniteUnite th thththeeee Right RightRightRight an ananan o ooovvvverallerallerallerall vict victvictvictororororyyyy..... -

Laura Loomer Exceeds Pre-Ban Twitter Following on Parler with 300K Followers

This publication is not affiliated with Laura Loomer for Congress. For more information visit LauraLoomerforCongress.com HOME TIP LINE CONTENT BY CATEGORY GET MY EMAILS DONATE SHOP ADVERTISE WITH US CONTACT ME SEE LAURA LOOMER ON DRUDGE REPORT Laura Loomer Exceeds Pre-Ban Twitter Following on Parler With 300k Followers Haley Kennington P O S T E D O N J U N E 2 4 , 2 0 2 0 SUPPORT LAURA’S WORK Share On Facebook Tweet It GET LAURA’S NEWSLET T ER This week marks a special milestone for investigative journalist and now Republican Congressional candidate in Florida District 21, Laura Loomer. After having been permanently banned from Twitter, Loomer moved over to free speech social media platform Parler, and not only brought her followers with her, but has now exceeded the amount of followers she had “pre-ban” on Twitter in 2018. Join Our Newsletter Enter your email Subscribe Privacy - Terms FOLLOW ME ON PARLER! FOLLOW ME ON T ELEGRAM! Loomer announced the landmark achievement Wednesday in a post on Parler: “I just became the first deplatformed person to exceed my Pre-Ban Twitter following here on @parler. When I was banned, people on the Left and Right cheered on the digital extermination of my persona. They said my career was over. FOREVER. Yet, here I am. SUBSCRIBE T O MY YOUT UBE CHANNEL Through my historic and unprecedented Congressional race in Florida’s 21st Congressional District, I am proving everyone wrong while making history. I’m on a mission to CANCEL CANCEL CULTURE and get elected to the United States Congress to ensure that no other American citizen is ever silenced the way I’ve been silenced. -

Alt-Reality Leaves Its Mark on Presidential

Fall Dispatches > CHARLES J. SYKES Alt-reality leaves its mark on presidential campaign With the arrival of fall, an anxious electorate increas- ingly feels like the kids in the back seat asking their parents, “Are we there … yet?” Some of us are even old enough to remember when round-the-clock television commercials were the most annoying aspect of our endless political campaigns. That now seems a calmer, gentler time. support is not a wise decision of his,” Palin continued. Palin soon was joined by such conservative luminaries as Ann Coulter and Michelle Malkin, who parachuted into None of the above Ryan’s district on behalf of his opponent, Paul Nehlen, who The current mood was captured in a late August focus also enjoyed the full-throated group held in Brookfield, Wisconsin. Reported The Washing- support of the alt-reality ton Post: conservative media. Foremost “For a small group of undecided among Nehlen’s media cheer- voters here, the presidential choices leaders was Breibart.com, this year are bleak: Hillary Clinton which headlined his momen- is a ‘liar’ with a lifetime of political tum on a nearly daily basis. skullduggery and a ruthless agenda for “Ann Coulter lights Wis- power, while Donald Trump is your consin on fire for Paul Nehlen ‘drunk uncle’ who can’t be trusted against Paul Ryan: ‘This to listen even to the good advice he’s is it, this is your last chance paying for. to save America,’ ” Breitbart “Describing the election as a headlined. On the day of cesspool, 12 swing voters participat- the Aug. -

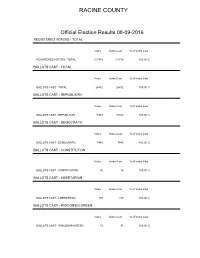

Final Summary Report 8-9-2016

RACINE COUNTY Official Election Results 08-09-2016 REGISTERED VOTERS - TOTAL Votes Votes Cast % of Votes Cast REGISTERED VOTERS - TOTAL 113718 113718 100.00 % BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL Votes Votes Cast % of Votes Cast BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL 26472 26472 100.00 % BALLOTS CAST - REPUBLICAN Votes Votes Cast % of Votes Cast BALLOTS CAST - REPUBLICAN 18342 18342 100.00 % BALLOTS CAST - DEMOCRATIC Votes Votes Cast % of Votes Cast BALLOTS CAST - DEMOCRATIC 7845 7845 100.00 % BALLOTS CAST - CONSTITUTION Votes Votes Cast % of Votes Cast BALLOTS CAST - CONSTITUTION 16 16 100.00 % BALLOTS CAST - LIBERTARIAN Votes Votes Cast % of Votes Cast BALLOTS CAST - LIBERTARIAN 107 107 100.00 % BALLOTS CAST - WISCONSIN GREEN Votes Votes Cast % of Votes Cast BALLOTS CAST - WISCONSIN GREEN 31 31 100.00 % RACINE COUNTY Party Preference Votes Votes Cast % of Votes Cast Republican 16532 26470 62.46 % Democratic 6295 26470 23.78 % Constitution 14 26470 0.05 % Libertarian 63 26470 0.24 % Wisconsin Green 18 26470 0.07 % OVER VOTES 7 26470 0.03 % UNDER VOTES 3541 26470 13.38 % United States Senator Votes Votes Cast % of Votes Cast Ron Johnson 15284 18357 83.26 % WRITE-IN 0 18357 0.00 % OVER VOTES 0 18357 0.00 % UNDER VOTES 3073 18357 16.74 % Representative in Congress, District 1 Votes Votes Cast % of Votes Cast Paul Ryan 15214 18356 82.88 % Paul Nehlen 2666 18356 14.52 % WRITE-IN 0 18356 0.00 % OVER VOTES 0 18356 0.00 % UNDER VOTES 476 18356 2.59 % State Senator, District 22 Votes Votes Cast % of Votes Cast WRITE-IN 14 2779 0.50 % OVER VOTES 0 2779 0.00 % UNDER VOTES 2765 -

Meaning, Choice and Human Truth

Journal of Theoretical & Philosophical Criminology Response to mass shooting 2020, July/August Vol 12: 80-97 DeValve Journal of Theoretical & Philosophical Criminology ISSN: 2166-8094 Jtpcrim July/August 2020: 12:80-97 ______________________________________ Reconsidering the Response to Mass Violence: Meaning, choice and human truth. 1 Michael DeValve, Bridgewater State University Corresponding Author: Michael J. DeValve, PhD, Department of Criminal Justice Fayetteville State University 321K LTB 1200 Murchison Road Fayetteville, NC 28301 [email protected] 910.489.9157 @Karunaprof (Twitter) 1 The author wishes to express deepest gratitude to J.B. Goss, Richard Quinney, John DeValve, Jeanne DeValve and Aaron Pycroft and David Polizzi for their kind and constructive feedback on this work. 80 Journal of Theoretical & Philosophical Criminology Response to mass shooting 2020, July/August Vol 12: 80-97 DeValve Introduction On the first day of August, 1966, an Eagle Scout and honorably discharged Marine killed his mother and wife, then carried weapons, ammunition, and supplies to the roof of the University of Texas tower. From his perch and with his training, he was able to kill fifteen and wound more than twenty. Some years later a retired accountant living in a sleepy community outside of Las Vegas, having squirreled away more than twenty weapons, hundreds of rounds of ammunition, and tools to make camera peepholes and barricades in a high hotel suite overlooking an outdoor music venue, authored the bloodiest mass shooting in American history. Cheri Maples was a police officer, district attorney, and dharma teacher. She was a beacon of wisdom, inspiration and lovingkindness to thousands, me included. -

Barring Immoral Speech in Patent and Copyright

SMU Law Review Volume 74 Issue 1 Article 5 2021 Barring Immoral Speech in Patent and Copyright Ned Snow University of South Carolina School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Part of the First Amendment Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Ned Snow, Barring Immoral Speech in Patent and Copyright, 74 SMU L. REV. 163 (2021) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol74/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. BARRING IMMORAL SPEECH IN PATENT AND COPYRIGHT Ned Snow* ABSTRACT In the past three years, the Supreme Court has twice ruled that Con- gress’s moral bars to trademark protection violate the First Amendment. Those rulings raise a simple question in other areas of intellectual property. Does the First Amendment preclude Congress from denying patent or cop- yright protection based on a moral reason? Congress, for instance, might deny patent protection for inventions directed toward the consumption of marijuana. Inventors would accordingly choose not to disclose knowledge about those inventions to the public, and the denial would chill their speech. Similarly, Congress would chill speech if it denied copyright pro- tection for moral reasons. A copyright bar to statues of the Confederacy, for instance, would deter artists from speaking such content. Hence, through patent and copyright, Congress might seek to influence speech in accord with its moral viewpoint. -

JIHADIST TERRORISM 17 YEARS AFTER 9/11 a Threat Assessment

PETER BERGEN AND DAVID STERMAN JIHADIST TERRORISM 17 YEARS AFTER 9/11 A Threat Assessment SEPTEMBER 2018 About the Author(s) Acknowledgments Peter Bergen is a journalist, documentary producer, The authors would like to thank Wesley Je�eries, John vice president for global studies & fellows at New Luebke, Melissa Salyk-Virk, Daiva Scovil, and Tala Al- America, CNN national security analyst, professor of Shabboot for their research support on this paper. The practice at Arizona State University where he co- authors also thank Alyssa Sims and Albert Ford, who directs the Center on the Future of War, and the co-authored the previous year’s assessment which author or editor of seven books, three of which were forms the basis of much of this report. New York Times bestsellers and four of which were named among the best non-�ction books of the year by The Washington Post. David Sterman is a senior policy analyst at New America and holds a master's degree from Georgetown’s Center for Security Studies. About New America We are dedicated to renewing America by continuing the quest to realize our nation’s highest ideals, honestly confronting the challenges caused by rapid technological and social change, and seizing the opportunities those changes create. About International Security The International Security program aims to provide evidence-based analysis of some of the thorniest questions facing American policymakers and the public. We are focused on South Asia and the Middle East, extremist groups such as ISIS, al Qaeda and allied groups, the proliferation of drones, homeland security, and the activities of U.S.