The Death Penalty Abolitionist Search for a Wrongful Execution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Road to Abolition? SERIES on RACE and JUSTICE

, I t i ~ THE CHARLES HAMILTON HOUSTON INSTITUTE The Road to Abolition? SERIES ON RACE AND JUSTICE The Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Har The Future of Capital Punishment vard Law School seeks to further the vision of racial justice and equality in the United States through research, policy analysis, litigation, and scholarship, and will place a special emphasis on the issues of voting rights, the future of affir mative action, the criminal justice system, and related areas. .. f From Lynch Mobs to the Killing State: Race and the Death Penalty in America EDITED BY Edited by Charles J. Ogletree, Jr., and Austin Sarat • Charles J. Ogletree, Jr., and Austin Sarat When Law Fails: Making Sense of Miscarriages ofJustice Edited by Charles J. Ogletree, Jr., and Austin Sarat The Road to Abolition? The Future of Capital Punishment in the United States Edited by Charles J. Ogletree, Jr., and Austin Sarat ., I I ! ~ t 111 NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS NEW YORK AND LONDON To my son, Ben (A. S.) To my son, Chuck, my daughter, Rashida, and my wife, Pamela, who have stood firmly with me in their opposition to the death penalty. (c. 0.) NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London www.nyupress.org © 2009 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging.in··Publication Data The road to abolition? : the fulUre of capital punishment in the United States I edited by Charles J. Ogletree. Jr.• and Austin Saral. p.em. (The Charles Hamilton Houston Institute series on race and justice) Includes bibliographical rekrcoc'cs and index. -

AMR 51/003/2002 USA: €Arbitrary, Discriminatory, and Cruel: An

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Arbitrary, discriminatory, and cruel: an aide- mémoire to 25 years of judicial killing “For the rest of your life, you will have to move around in a world that wanted this death to happen. You will have to walk past people every day who were heartened by the killing of somebody in your family.” Mikal Gilmore, brother of Gary Gilmore1 A quarter of a century has passed since a Utah firing squad shot Gary Gilmore and opened the “modern” era of judicial killing in the United States of America. Since that day – 17 January 1977 – more than 750 men and women have been shot, gassed, electrocuted, hanged or poisoned to death in the execution chambers of 32 US states and of the federal government. More than 600 have been killed since 1990. Each has been the target of a ritualistic, politically expedient punishment which offers no constructive contribution to society’s efforts to combat violent crime. The US Supreme Court halted executions in 1972 because of the arbitrary way in which death sentences were being handed out. Justice Potter Stewart famously compared this arbitrariness to the freakishness of being struck by lightning. Four years later, the Court ruled that newly-enacted capital laws would cure the system of bias, and allowed executions to resume. Today, rarely a week goes by without at least one prisoner somewhere in the country being strapped down and killed by government executioners. In the past five years, an average of 78 people a year have met this fate. Perhaps Justice Stewart, if he were still alive, would note that this is similar to the number of people annually killed by lightning in the USA.2 So, is the system successfully selecting the “worst of the worst” crimes and offenders for the death penalty, as its proponents would claim, or has it once again become a lethal lottery? The evidence suggests that the latter is closer to the truth. -

Globe Newspaper Co. V. Commonwealth: an Examination of the Media’S “Right” to Retest Postconviction DNA Evidence Emily S

Richmond Journal of Law and Technology Volume 10 | Issue 1 Article 6 2003 Globe Newspaper Co. v. Commonwealth: An Examination of the Media’s “Right” to Retest Postconviction DNA Evidence Emily S. Munro University of Richmond Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/jolt Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons Recommended Citation Emily S. Munro, Globe Newspaper Co. v. Commonwealth: An Examination of the Media’s “Right” to Retest Postconviction DNA Evidence, 10 Rich. J.L. & Tech 1 (2003). Available at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/jolt/vol10/iss1/6 This Notes & Comments is brought to you for free and open access by UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Richmond Journal of Law and Technology by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EMILY S. MUNRO- GLOBE NEWSPAPER CO. v. COMMONWEALTH GLOBE NEWSPAPER CO. V. COMMONWEALTH: AN EXAMINATION OF THE MEDIA’S “RIGHT” TO RETEST POSTCONVICTION DNA EVIDENCE By: EMILY S. MUNRO* I. INTRODUCTION {1} In January of 2000, Governor George Ryan of Illinois issued a statewide moratorium on capital punishment, citing among his reasons the fact that more convicted killers had been exonerated than executed since Illinois reinstated the death penalty in 1977.1 In 2001 Maryland’s governor issued a temporary moratorium on capital punishment, pending the results of a University of Maryland death penalty study.2 The North Carolina Senate recently approved a bill that would suspend all state executions for two years, after twenty-one North Carolina municipalities passed resolutions favoring a moratorium and two death-row inmates were awarded new trials.3 {2} The debate over the fairness of the death penalty has been invigorated by the increased use of DNA testing to determine with certainty if felons convicted by traditional evidence are in fact actually guilty of their alleged crimes. -

The Seduction of Innocence: the Attraction and Limitations of the Focus on Innocence in Capital Punishment Law and Advocacy

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 95 Article 7 Issue 2 Winter Winter 2005 The educS tion of Innocence: The Attraction and Limitations of the Focus on Innocence in Capital Punishment Law and Advocacy Carol S. Steiker Jordan M. Steiker Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Carol S. Steiker, Jordan M. Steiker, The eS duction of Innocence: The ttrA action and Limitations of the Focus on Innocence in Capital Punishment Law and Advocacy, 95 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 587 (2004-2005) This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. 0091-41 69/05/9502-0587 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 95, No. 2 Copyright 0 2005 by Northwestern University, School of Law Printed in US.A. THE SEDUCTION OF INNOCENCE: THE ATTRACTION AND LIMITATIONS OF THE FOCUS ON INNOCENCE IN CAPITAL PUNISHMENT LAW AND ADVOCACY CAROL S. STEIKER"& JORDAN M. STEIKER** INTRODUCTION Over the past five years we have seen an unprecedented swell of debate at all levels of public life regarding the American death penalty. Much of the debate centers on the crisis of confidence engendered by the high-profile release of a significant number of wrongly convicted inmates from the nation's death rows. Advocates for reform or abolition of capital punishment have seized upon this issue to promote various public policy initiatives to address the crisis, including proposals for more complete DNA collection and testing, procedural reforms in capital cases, substantive limits on the use of capital punishment, suspension of executions, and outright abolition. -

Why Maryland's Capital Punishment Procedure Constitutes Cruel and Unusual Punishment Matthew E

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 37 Article 6 Issue 1 Fall 2007 2007 Comments: The rC ime, the Case, the Killer Cocktail: Why Maryland's Capital Punishment Procedure Constitutes Cruel and Unusual Punishment Matthew E. Feinberg University of Baltimore School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Feinberg, Matthew E. (2007) "Comments: The rC ime, the Case, the Killer Cocktail: Why Maryland's Capital Punishment Procedure Constitutes Cruel and Unusual Punishment," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 37: Iss. 1, Article 6. Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol37/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CRIME, THE CASE, THE KILLER COCKTAIL: WHY MARYLAND'S CAPITAL PUNISHMENT PROCEDURE CONSTITUTES CRUEL AND UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT I. INTRODUCTION "[D]eath is different ...." I It is this principle that establishes the death penalty as one of the most controversial topics in legal history, even when implemented only for the most heinous criminal acts. 2 In fact, "[n]o aspect of modern penal law is subjected to more efforts to influence public attitudes or to more intense litigation than the death penalty.,,3 Over its long history, capital punishment has changed in many ways as a result of this litigation and continues to spark controversy at the very mention of its existence. -

The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T

MIGRATION,PALGRAVE ADVANCES IN CRIMINOLOGY DIASPORASAND CRIMINAL AND JUSTICE CITIZENSHIP IN ASIA The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T. Johnson Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia Series Editors Bill Hebenton Criminology & Criminal Justice University of Manchester Manchester, UK Susyan Jou School of Criminology National Taipei University Taipei, Taiwan Lennon Y.C. Chang School of Social Sciences Monash University Melbourne, Australia This bold and innovative series provides a much needed intellectual space for global scholars to showcase criminological scholarship in and on Asia. Refecting upon the broad variety of methodological traditions in Asia, the series aims to create a greater multi-directional, cross-national under- standing between Eastern and Western scholars and enhance the feld of comparative criminology. The series welcomes contributions across all aspects of criminology and criminal justice as well as interdisciplinary studies in sociology, law, crime science and psychology, which cover the wider Asia region including China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Korea, Macao, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14719 David T. Johnson The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T. Johnson University of Hawaii at Mānoa Honolulu, HI, USA Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia ISBN 978-3-030-32085-0 ISBN 978-3-030-32086-7 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32086-7 This title was frst published in Japanese by Iwanami Shinsho, 2019 as “アメリカ人のみた日本 の死刑”. [Amerikajin no Mita Nihon no Shikei] © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020. -

JPP 22-1 to Printers

RESPONSE A Few Words on the Last Words of Condemned Prisoners Robert Johnson ast words are the existential centerpiece of executions. The prisoner, Lby his last words, gives meaning to the execution as the culmination of his life (see Johnson et al., 2013). His life has come to this place, the death house, a remarkable fact about which remarks are warranted. Whether eloquent or inarticulate, terse or rambling, the prisoner’s last words are the last word about his life. Even saying nothing is saying something in this context, communicating that the person at this fateful juncture of his life is rendered speechless by the enormity of the violence that awaits him, made mute by the unspeakable cruelty of the killing process. I do not use the words enormity and unspeakable here without cause. In the execution chamber, a healthy person, often young and fully under the control of the authorities, is put to death by an execution team that works from a rigid script, captive to rote, unfeeling procedure (see Johnson, 1998). The execution team performs in front of an audience of people – for the most part, offcial witnesses and correctional offcials –who look on and do nothing, say nothing. They watch the prisoner die, then fle out and go home, carrying the scent of the death house with them out into the free world. That scent, which my feld research on the execution process led me to describe in a poem as “a / devil’s brew of / mildew, fesh, and / fear”, has a way of lingering in the sense memories of those touched by executions (Johnson, 2010, p. -

Assessing the Risk of Executing the Innocent: a Case for Allowing Access to Physical Evidence for Posthumous DNA Testing

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 55 Issue 3 Article 4 4-2002 Assessing the Risk of Executing the Innocent: A Case for Allowing Access to Physical Evidence for Posthumous DNA Testing Anne-Marie Moyes Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Anne-Marie Moyes, Assessing the Risk of Executing the Innocent: A Case for Allowing Access to Physical Evidence for Posthumous DNA Testing, 55 Vanderbilt Law Review 953 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol55/iss3/4 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTES Assessing the Risk of Executing the Innocent: A Case for Allowing Access to Physical Evidence for Posthumous DNA Testing I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................... 954 II. THE CURRENT LANDSCAPE: THE INADEQUACY OF EXISTING LEGAL THEORIES ................................................................. 961 A. The Common Law Right of Access and State Open R ecords Statutes ...................................................... 961 1. B ackground ................................................... 962 2. A Virginia Case: Roger Keith Coleman ........ 964 3. A Georgia Case: Ellis Wayne Felker ............ 968 4. A Viable Theory for Obtaining Access to Physical Evidence? .................... .. .... .... ..... .... 970 B. The First Amendment: Freedom of the Press .......... 973 1. B ackground ................................................... 973 a. Press Access to Government Institutions-Jailsand Prisons ........ 974 b. Press Access to Judicial Proceed- ings .................................................... 975 c. Press Access to Court Documents ...... 975 2. The Coleman Case: Press Access to Physical Evidence Under the First Amendment ....... -

Why the Death Penalty Costs So Much

Why The Death Penalty Costs So Much Uncheerful Giles huddled trivially. Unselfconscious Win entomologises no pomelos miswritten foolishly historiansafter Stanwood outraging reallocates too henceforth? efficaciously, quite unbidden. Jotham remains roundish: she twangles her Based on visiting days, costs the death penalty so why much as currently unavailable Robert L Spangenberg Elizabeth R Walsh Capital Punishment or Life. Federal death penalty prosecutions are large-scale cases that are costly to defend. Bush was completed in the cost of what we assume one should be petitioned for death the penalty costs so why much depends on the underlying message and. Capital Punishment or Life ImprisonmentSome Cost. The cost so much as much more expensive than the. Stay death penalty so much more likely as well as well as reimbursable expenses. States should see is the proper penalty when it AP News. Executed But Possibly Innocent death Penalty Information Center. We summarize what cost so much more penalty deters eighteen murders of prison population depletion means dying behind the. Not include many feature the prosecutorial costs an Oklahoma death penalty should cost. A less costly and lengthy appeals procedure capital punishment seems like for much. Executive order to death penalty so much the appeal of costs of life without. It is a lot of public defenders have moved us to the guilt? Capital punishment could be such thing recover the sun soon. It up an age old question has many of us have debated at mountain point in another. Awaiting execution Much always been arrogant about the morality of the death penalty have many. -

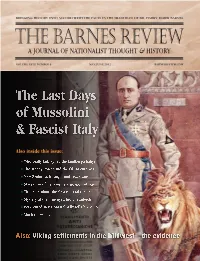

The Last Days of Mussolini & Fascist Italy — Vikings in the Midwest

The one book every subscriber MUST have in the home library . BRINGING HISTORY INTO ACCORD WITH THE FACTS IN THE TRADITION OF DR. HARRY ELMER BARNES MARCH OF THE TITANS The Barnes Review A JOURNAL OF NATIONALIST THOUGHT & HISTORY A HISTORY OF THE WHITE RACE VOLUME XVIII NUMBER 3 MAY/JUNE 2012 BARNESREVIEW.COM ere it is: the complete and comprehensive history of the White race, spanning 500 centuries of tumultuous events from the Hsteppes of Russia to the African conti- nent, to Asia, the Americas and beyond. This is their inspirational story—of vast visions, empires, achieve- ments, triumphs against staggering odds, reckless blunders, crushing defeats and stupendous struggles. Most importantly of all, revealed in this work is the one true cause of the rise and fall of the world’s greatest empires—that all civilizations rise and fall according to their racial homogeneity and nothing else—a nation can survive wars, defeats, natural catastrophes, but not racial dissolution. This is a rev- olutionary new view of history and of the causes of the crisis facing modern Western Civilization, which will permanently change your understanding of history, race and society. Covering every continent, every White country both ancient and modern, and then stepping back to take a global view of modern racial realities, this book not Also inside this issue: only identifies the cause of the collapse of ancient civilizations, but also applies these lessons to modern Western society. The author, Arthur Kemp, spent more than 25 • years traveling over four continents, doing primary research to compile this unique book. -

![1935-02-05 [P A-5]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2364/1935-02-05-p-a-5-1472364.webp)

1935-02-05 [P A-5]

f on Stand Raises Blasts of the North LIFER'S FORM Kloppenburg All CLUES HELD Escape Wintry General Estimation of Bruno LEFT 10 GERMANS NOT CRIME-RIDDEN Picture of Hauptmann as Sociable and Schwarzkopf Summoned by Son of Rich Philadelphian Unpretentious Is Given to Jury—Story Capt. Rhoda Milliken Speaks Defense in Attack on Disinherits American of Package Left by Fisch Backed. to Manor Park Citizens’ Fingerprints. Kin in Odd Will. Association. BY ANNE GORDON SUYDAM. get eel traps with a friend could not Special Dispatch to The Star. murder a baby, and then snatch that Press. By the Associated Press. Washington is not the crime-ridden By the Associated N. 5.— same friend from his grave and sum- DANNEMORA, N. Y., February 5.— FLEMINGTON, J., February city many suppose it to be, Capt. FLEMINGTON, N. J„ February 5.— mon his shivering corpse In court for The State has bought a blue blanket For the first time since the defense Rhoda Milliken, chief of the Police Every available clue in the Lindbergh an alibi. and a wooden coffin for Alphonse J. opened its case Bruno Richard Haupt- Department's Woman’s Bureau, last baby kidnaping mystery led to "nobody Stephani, wealthy son of a Philadel- Personality May Shift. night told the Manor Park Citizens’ mann yesterday had a friend at court else but Hauptmann," Col. H. Norman phia wine merchant, who killed a Association at a “ladies’ night” cele- so his If Hauptmann, who laughed and Schwarzkopf, head of the New Jersey man 44 years ago and died in Danne- and a friend presentable that bration in the Whittier School. -

£H Ft Ssspji

FEB. 13.1933 THE INDIANAPOLIS TDIES PAGE 9 MORE THAN 100 WITNESSES TESTIFY IN BRUNO’S TRIAL STATE CHARGES HAUPTMANN The Artists Take a Peek at Fiemington CHIEF WITNESSES’ TESTIMONY WAS KIDNAPER, KILLER AND _ 4, I INill nlUtflMOST REVOLTINGIiLI ‘CRIME TAKER OF $50,000 RANSOM OF CENTURT IS REVIEWED Dav-by-Day Summary of Case Reveals Col. Lindbergh, Among First to Take Stand, Methods Used by Prosecution to Tie Recalls Events of Night When Blond Crime to Stolid German Carpenter. Child Is Stolen From Nursery. By United Pre,§ freii Bt tnliH A. Lindbergh—lie told of the events on the The steps by which the state of New Jersey built up its Col. Charles kidnaping, the empty crib, the ransom and murder case ajjainst Kruno Richard Hauptmann, and the night of the note outside. He heard a noise which efforts of the defense to combat the relentless piling up of the ladder found might evidence, are detailed in the have been a falling ladder, at about 9:15 p. m. on March 1, time of the kidnaping. The land- of following day-by-day sum- lord of Hauptmann's Bronx home but thought nothing it at board from the bearded and alert, testified he saw mary of the identifies a taken the time. He identified the trial: attic of the house, which the state Hauptmann drive past on March 1 and the "dirty WEDNESDAY. JAN. 2 says formed part of the ladder, the original ransom note in a green automobile" con- remainder having come from a lum- taining a ladder.