The Endless Run Reflections on the 2008 Comrades

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comrades Marathon

Comrades Marathon 14 June 2020 Comrades Marathon is arguably the greatest Ultra Marathon in the world where athletes travel from all over the globe to combine muscle and mental strength to conquer approximately 90 kilometers between cities of Pietermaritzburg and Durban. The event owes its beginnings to the vision of one man, World War I veteran Vic Clapham. The 2019 Comrades event will be a "Down run” starting at the City Hall in Pietermaritzburg and finishing in Scottsville Racecourse in Durban. For 16 years Travelling Fit has been organising packages to the Comrades Marathon and we are delighted to be able to offer you a five (5) night Marathon package including one (1) night pre-race in Pietermaritzburg for a more much more stress free experience on race morning. Travelling Fit is an accredited travel agency which offers a full range of services to our clients. This enables us to book your flights and additional touring to help us assist you in creating your perfect holiday experience. PACKAGE 1 SOUTHERN SUN ELANGENI 4 STAR PACKAGES INCLUDE: Guaranteed Race Entry to the 2020 Comrades Marathon (runners only) 4 nights’ Accommodation in Durban at Southern Sun Elangeni Maharani (10-12 Jun and 14 Jun 2020) 1-night post-race accommodation at Southern Sun Pietermaritzburg (13 Jun 2020) Return Airport Transfers Hotel Distance from the Finish Line: 3km. Full Buffet Breakfast daily Transport will be provided from the finish line back to the hotel. Group warm up Run Exclusive to Travelling Fit clients. The Southern Sun Elangeni is just meters from the best beaches, the 4km Escort to expo for race bib collection boardwalk and Durban’s major attractions. -

Comrades Runners Snapped on the Road Wrapped up in Goodwill Local

15 June 2018 Your FREE Caxton Local Newspaper - www.higwaymail.co.za Wrapped up in goodwill Page 2 Comrades runners snapped on the road Dad to the rescue: Real life super hero and dad, station commander, Rajan Arunachallem from Queensburgh Fire Station wakes up daily with a mission to save lives even though at times it means less time to spend with his children. The editor and staff of Queensburgh News wish all dads a Happy Father's Day. PHOTO: Khethukuthula Lembethe-Xulu Page 10 Local karate Khethukuthula into a career in public service buildings,” he said. I have inspired my son to said he is not sure what the Lembethe-Xulu and help the community. Many He added that in essence, join the fi re department. My family has planned for him kids excel kids want to become police saving people's lives is the best daughter also wants to save but he hopes it involves him QUEENSBURGH resident, offi cers but I moved towards reward. lives which is why she wants spending time with them. fi refi ghter and father, Rajan being a fi refi ghter,” he said. Rajan's children look up to become a doctor,” he added. “Because it’s a Sunday, the Arunachallem has dedicated According to Rajan the best to him and see him as a hero. Rajan said he treasures the day will start off with going to 19 years of his life to serve his thing about being a fi refi ghter Titus (15) and Chloe (12) both days he has off work because church and the rest I leave to community. -

Further Enquiries

THIS RACE IS RUN UNDER THE RULES OF IAAF, ASA, KZNA & CMA REGISTRATION VENUE BEST “UP RUN” TIME PRIZE MONEY & AWARDS DURBAN PIETERMARITZBURG Should the Winners (man and woman) of the 2019 Comrades Marathon break the Best Time previously All prizes including prize money, trophies and/or special medals Comrades Marathon House Durban Exhibition Centre recorded for the “Up Run”, he or she will receive a cash payment will only be issued once Doping Control results have been 18 Connaught Road Walnut Road of R 500 000,00 received and subject to clearance. All prize money is subject to Scottsville South African tax laws and may take up to 3 months to process. Durban Pietermaritzburg THE BEST TIME PREVIOUSLY RECORDED 5:24:49 by Leonid Shvetsov in 2008 OFFICIAL CHARITY DATES & TIMES 6:09:24 by Elena Nurgalieva in 2006 The Comrades Marathon Amabeadibeadi Campaign consists of Thursday 6th June 2019 10h00 - 19h00 six official charities namely: Friday 7th June 2019 09h00 - 19h00 AGE CATEGORIES CHOC (Childhood Cancer Foundation of South Africa), An athlete is not eligible for a prize in more than one age Saturday 8th June 2019 09h00 - 17h00 Community Chest Durban & Pietermaritzburg, Hillcrest Aids category, i.e. an athlete is only eligible for a prize in the age Centre Trust, Hospice Palliative Care Association of South Africa, category applicable to him/her or the younger category chosen Wildlands Conservation Trust and World Vision South Africa. If you are unable to collect your race number package, a third by him/her provided he/she is wearing the relevant ASA An Amabeadibeadi gift will be enclosed in your race number party can collect this on your behalf providing they have approved age category tag. -

POLTICIZING the RACE the Silent Protest of 1981

WORK IN PROGRESS. PLEASE DO NOT CITE. Jo-Anne Tiedt, ‘Contesting Comrades’: Writing the Comrades Marathon on the politically charged roads of South Africa, 1980 – 1990. (Honours dissertation, UKZN, 2009). POLTICIZING THE RACE The silent protest of 1981 …they accused us through the media… of politicizing the race… they said we were making it into a political issue, and we said in response that “no, the Comrades committee had politicized it by linking [placing it on] it to Republic Day”. Republic Day had enormous, to our way if thinking… political symbolism. Because under this Republic you are celebrating apartheid.1 The historical narrative of the Comrades Marathon is far more complicated than what is portrayed in those narratives officially endorsed by the Comrades Marathon Association (CMA). The narratives depicted, attempt to portray a road race which is almost completely isolated from the political context during which it was staged. They have endeavoured thorough such narratives, and they still do, to ignore the effect of apartheid on those living within the borders of South Africa, steadfast in the idealistic belief that sport and politics are two completely separate social endeavours. The official narratives as produced by the CMA, and those history books they endorse, cover the race from its inception until present day. They tell the history of a race considered to be one of the most prestigious ultra-marathons in the world. Yet, such a grand narrative seemingly separates itself from the different contexts in which it finds itself; it portrays the race and its runners as untainted by the racial policies and apartheid legislation which affected the country and infiltrated every aspect of South African society, including sport and therefore the Comrades Marathon. -

Comrades May2019 Presentati

You have done the hard yards You have sacrificed You have qualified You have earned your place at the starting line Do not do anything stupid that will undo all the work you have put in It is your sole responsibility to get to the start line… …Injury Free …Healthy …Well Rested & Recovered … Excited to run WCAC Starting List - 2019 • 62 have qualified and ‘said’ they are going Gender: • 195 medals amongst these • 24 Females (39%) • 17 back-to-back runners • 38 Males (61%) • 19 Novice runners (1/3rd) Seeding: • Most experienced runners: • B = 3 • Willie Coetzee – 21 medals • C = 11 • D = 11 • Martin Venter – 21 medals • E = 2 • Isabel Steenkamp – 17 medals • F = 10 • Andre Pepler – 16 medals • G = 10 • Mitch Levin – 12 Medals • H = 16 • Donald Scott – 11 medals • Marius Heydenreich – 11 medals First Male WCAC First Female WCAC Don Oliver – First Novice WCAC Comrades Up Run Route in Perspective Suikerbossie Malanshoogte Next 35km is undulating climbs Big Mama Imtinebe School Perlemoen Umlaas Rd First 35km is unrelenting climbs Bothas Hill Inchanga Radnor #@!$! Alverston Tower Polly Shortts Camperdown Little Polly’s Redhill Hillcrest Harrison Flats Chicken Farms Drummond Fields Hill Little Ou Kaapse Comrades Wall & Arthurs Seat Cowies Hill Pinetown 45th Cutting 1st Support 2nd Support Tollgate Table Table Are you Ready? Recovery Period Comrades Day Race Strategy Travel / Logistics Prep Taper Period 87 km 1650 m elevation Days leading up to Comrades – Pointers ▪You will be ratty, its normal and part of the tapering process ▪Avoid anyone who is sick ▪Don’t over-eat on junk food ▪Devise your pacing chart, all logistics, tracking apps, inform seconds/family/etc ▪Start your mental prep and Visualise the positive ▪Don’t be silly and play games that could cause injury ▪Virtual flu / niggles – ignore this. -

32 Drsep-Dec01 Comrades

MEN: 1 Andrew KEHELE RSA 5:25:51 2 Leonid SHVETSOV RUS 5:26:28 3 Vladimir KOTOV BLR 5:27:21 Comrades 4 Alexey VOLGIN RUS 5:27:40 5 Fusi NHLAPO RSA 5:30:38 6 Grigory MURZIN RUS 5:32:59 7 Dmitry GRISHIN RUS 5:36:04 8 Sarel ACKERMANN RSA 5:36:50 at last 9 Walter NKOSI RSA 5:38:15 10 Michael MPOTOANE RSA 5:38:43 Comrades Marathon, South Africa, 16 June 2001 June 16, Youth Day, is a The author, BLANCHE MOILA, was the first probably the best thing I have special day in South Africa. It ever done in my life. Nothing black woman to win national (Springbok) could have prepared me for the commemorates the day in colours for athletics, back in apartheid 1976 on which the black overwhelming feeling of days. She has won national titles on youth of Soweto lost lives anticipation and excitement as I the road and cross-country. Her stood on the start line. The spirit protesting against the personal best times include 4:34 and cameradie of the race, and education policies of the then the ecstasy of crossing the finish apartheid government. (1500m), 75:00 (half marathon) and 2:41 (marathon). line was like nothing I had experienced before. On the same day another She beat Zola Budd to the title of special and unique event takes South African Sportswoman of the More and more international place in Kwazulu-Natal: the runners are taking part in this Comrades Marathon - the Year in 1985, and earlier this year ‘True Test of the Human Spirit’. -

The Natal Society Office Bearers 2000 - 2001

THE NATAL SOCIETY OFFICE BEARERS 2000 - 2001 President S.N. Roberts Vice-Presidents T.B. Frost Professor A. Kaniki Trustees MJ.e. Daly Professor A. Kaniki S.N. Robelis Treasurers KPMG A.L. Nonnan Auditors Messrs Thornton-Dibb, Van der Leeuw and Partners Director le. Morrison Secretary Mrs M. Maxfield COUNCIL Elected Members S.N. Roberts (Chainnan) . Professor A. Kaniki (Vice Chairman) Professor A. M. Barrett M.H. Comrie J. H. Conyngham MJ.e. Daly J.M. Deane Professor W.R. Guest Mrs M. Msomi Miss N. Naidoo A.L. Singh Ms P.A. Stabbins EDITORIAL COMMITTEE OF NATALIA Editor M.H. Comrie Dr W.H. Bizley lM. Deane T.B. Frost F.E. Prins Professor W.R. Guest Dr D. Herbert Mrs S.P.M. Spencer Dr S. Vietzen G.D.A. Whitelaw Secretary DJ. Buckley Natalia 30 (2000) Copyright © Natal Society Foundation 2010 Natalia Journal ofthe Natal Society No. 30 December 2000 Published by Natal Society Library p.a. Box 415. Pietermaritzburg 3200. South Africa SA ISSN 0085-3674 Cover Picture King Twala's royal honlestead below Otto's Bluff Tlpeset hI' i14J !lvlanrick Prinfed hr iV(/{a/ H/itlwsS CO/JI/1/('/'c;a/ Printers (Ptr) Lrd Contents EDITORIAL ................................................................................ v PREVIOUSLY UNPUBLISHED PIECE A Byrne settler's experiences in early Natal She/agh Spencer ................................................................... ARTICLES Une souvenir du France Steven K otze ................. ............. ............. ....... ............ ............. 14 King Solomon's Mines at Otto's Bluff Stephen Coan.. .......... ......... .............. ........... ................... ........ 17 Mediation efforts in turbulent times lvfichael lVuttall .................................... .................................. 24 Memories of a country doctor's daughter Esnu? llennessy ...................................................................... 31 Peace on eaIih and mercy mild (KwaZulu-Natal Anglo-Boer War Centenary deties its critics) ./. -

Comrades Marathon 2018 Men – Profiles

COMRADES MARATHON 2018 MEN – PROFILES Nedbank Running Club - Administrative Head Office Tel: (012) 541 0577 Fax: (012) 541 3752 www.nedbankrunningclub.co.za CURRICULUM VITAE: Ludwick MAMABOLO PERSONAL INFORMATION SURNAME: Mamabolo FIRST NAMES: Ludwick COUNTRY: R.S.A DATE OF BIRTH: 14 April 1977 CLUB: Nedbank Running Club PERSONAL BEST PERFORMANCES Half Marathon 1:07:37 Marathon 2:20:48 50 km Road 2:49:55 Comrades Marathon Results Two Oceans 56km Results 2010 Down, 05:35:29, 2nd 2004, 03:19:44, 21st 2011 Up, 05:50:18, 7th 2008, 03:18:02, 11th 2012 Down, 05:31:03, 1st 2009, 03:14:43, 7th 2013 Up, 05:45:49, 4th 2010, 03:20:52, 18th 2014 Down, 05:33:14, 2nd 2011, 03:16:33, 18th 2016 Down, 05:24:05, 2nd 2012, 03:22:48, 25th 2017 Up, 05:42:40, 4th 2016, 03:17:52, 6th 2017, 03:21:42, 15th 2018, 03:35:27, 45th Annual Bests 2018 3rd Mall of The North (lima) 42km 02:34:58 5th Marula Festival (lima) 21km 01:11:58 Nedbank Running Club - Administrative Head Office Tel: (012) 541 0577 Fax: (012) 541 3752 www.nedbankrunningclub.co.za CURRICULUM VITAE: Lungile GONGQA PERSONAL INFORMATION SURNAME : Gongqa FIRST NAMES: Lungile COUNTRY: South-African DATE OF BIRTH: 22/02/1979 CLUB: Nedbank Running Club PERSONAL BEST PERFORMANCES Distance Time Area Date 5000m 14:12.47 Durban (RSA) 21.03.2010 10,000m 30:10.31 Stellenbosch (RSA) 13.03.2009 10 km Road 29:09 Mdantsane (RSA) 01.09.2013 12 km Road 35:39 Cape Town (RSA) 17.05.2015 15 km Road 45:20 Cape Town (RSA) 09.03.2013 Half Marathon 1:03:57 Port Elizabeth (RSA) 30.07.2016 Marathon 2:11:59 Cape Town (RSA) 20.09.2015 -

South African Distance Runners: Issues Involving Their Ni Ternational Careers During and After Apartheid Carrie A

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1999 South African Distance Runners: Issues Involving Their nI ternational Careers During and After Apartheid Carrie A. Lane Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Physical Education at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Lane, Carrie A., "South African Distance Runners: Issues Involving Their nI ternational Careers During and After Apartheid" (1999). Masters Theses. 1530. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1530 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates (who have written formal theses) SUBJECT: Permission to Reproduce Theses The University Library is receiving a number of request from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow these to be copied. PLEASE SIGN ONE OF THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university or the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University NOT allow my thesis to be reproduced because: Author's Signature Date thesis4.form South African Distance Runners: Issues Involving Their International Careers During and After Apartheid (TITLE) BY Carrie A. -

The Comrades Marathon

August 2011 Issue No. 184 The Comrades Marathon By Maurice Lee Comrades Marathon is actually an ultramarathon of about 90 kilometers (56 miles) that is run between Durban and Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. The race alternates each year between the “up” course starting in Durban and “down” course starting in Pietermaritzburg. The race was the idea of World War I veteran Vic Clapham to commemorate the South African soldiers killed during the war. Clapham, who had endured a 2,700 kilometer march through sweltering East Africa, wanted the run to be a unique test of the physical endurance of the entrants. Since the marathon distance was not defined as 26.2 miles until 1921, it was common to call any long distance run a “marathon”. On Monday, May 23, I boarded a Delta jet to begin my journey to Durban, South Africa. My journey took me from Oklahoma City to Atlanta where I boarded a 777 for the 15 hour non-stop flight to Johannesburg. From Johannesburg I boarded a South African Airways plane for the hour and 15 minute flight to Durban. The long flight from Atlanta to Johannesburg included three full meals, none of which were good, and all the individual entertainment I wanted. I went back and forth from watching movies or TV series to napping. They served plenty of water, and every few hours I walked around the plane. The short flight to Durban also included a meal which surprised me. You would be lucky to get peanuts on a flight that short in the U S. -

Comrades Marathon

COLLEGIANS HARRIERS By Mike Bath Collegians Harriers is one of the oldest athletic clubs in South Africa, and in its 70 year history has made a huge and lasting contribution to athletics in the country. Collegians Harriers began its existence on 24th January 1933 as the Maritzburg Harriers Athletic Cub, when the inaugural meeting of the small group of founders was presided over by the President of the Natal Amateur Athletic Association C.E.Sax Young with other members being Bert Bendzulla (first captain and secretary), B.du Toit, (vice- captain), F.van Vuuren, O.Mattison, H. McLeary, F.M. van Loenen, and D.J.Botha (Treasurer). Several prominent citizens of Pietermaritzburg supported the newly formed club. The club produced numerous athletic stars, to name but a few – Bert Bendzulla, for many years Natal 880 yards champion and record holder, SA champion and Empire Games trialist; Skonk Nicholson of Maritzburg College fame, SA 1000 yards record holder and S.A.Varsities champion, and many others who brought honour and glory to the club. In later years as Collegians Harriers, there emerged such greats as Piet van der Leeuw Springbok and SA .record holder, Dave Piper and Gordon Baker who performed and excelled at distances from the mile to the Comrades Marathon. As organisers of Comrades Marathon, perhaps the club’s crowning glory came in 1979 when the popular Collegians Harriers athlete Piet Vorster won the Comrades Marathon, in a time of 5:45:02, establishing a new record time for the up run. The club, over the years has organized numerous road races in the province. -

How It All Began

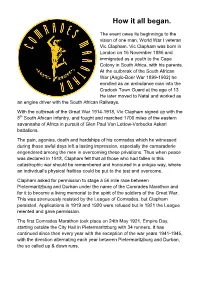

How it all began. The event owes its beginnings to the vision of one man, World War I veteran Vic Clapham. Vic Clapham was born in London on 16 November 1886 and immigrated as a youth to the Cape Colony in South Africa, with his parents. At the outbreak of the South African War (Anglo-Boer War 1899-1902) he enrolled as an ambulance man into the Cradock Town Guard at the age of 13. He later moved to Natal and worked as an engine driver with the South African Railways. With the outbreak of the Great War 1914-1918, Vic Clapham signed up with the 8th South African Infantry, and fought and marched 1700 miles of the eastern savannahs of Africa in pursuit of Glen Paul Von Lettow-Vorbecks Askari battalions. The pain, agonies, death and hardships of his comrades which he witnessed during those awful days left a lasting impression, especially the camaraderie engendered among the men in overcoming these privations. Thus when peace was declared in 1918, Clapham felt that all those who had fallen in this catastrophic war should be remembered and honoured in a unique way, where an individual’s physical frailties could be put to the test and overcome. Clapham asked for permission to stage a 56 mile race between Pietermaritzburg and Durban under the name of the Comrades Marathon and for it to become a living memorial to the spirit of the soldiers of the Great War. This was strenuously resisted by the League of Comrades, but Clapham persisted. Applications in 1919 and 1920 were refused but in 1921 the League relented and gave permission.