Rights Watch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNITED Kingdompolitical Killings in Northern Ireland EUR 45/001/94 TABLE of CONTENTS

UNITED KINGDOMPolitical Killings in Northern Ireland EUR 45/001/94 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 Killings by members of the security forces ........................................................... 3 Investigative Procedures: practice and standards ...................................... 8 The Use of Lethal Force: Laws and Regulations/International Standards ..................................................................................... 12 Collusion between security forces and armed groups ........................................ 14 The Stevens Inquiry 1989-90 ..................................................................... 14 The Case of Brian Nelson .......................................................................... 16 The Killing of Patrick Finucane .................................................................. 20 The Stevens Inquiry 1993 .......................................................................... 23 Other Allegations of Collusion .................................................................... 25 Amnesty International's Concerns about Allegations of Collusion ............ 29 Killings by Armed Political Groups ...................................................................... 34 Introduction ................................................................................................. 34 Human Rights Abuses by Republican Armed Groups .............................. 35 IRA Bombings -

THE APPARATUS of IMPUNITY? Human Rights Violations and the Northern Ireland Conflict: a Narrative of Official Limitations on Post-Agreement Investigative Mechanisms

THE APPARATUS OF IMPUNITY? Human rights violations and the Northern Ireland conflict: a narrative of official limitations on post-Agreement investigative mechanisms Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) © Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The material may be reproduced, free of charge, in any format or medium without specific permission, provided the reproduction is not for financial or material gain.The material must be reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. If the material is to be republished or issued to others, acknowledgement must be given to its source, copyright status, and date of publication. This publication is available on our website. CAJ Committee on the Administration of Justice 2nd Floor, Sturgen Building 9-15 Queen Street Belfast BT1 6EA Tel: 028 9031 6000 Fax: 028 9031 4583 [email protected] www.caj.org.uk ISBN 978 1 873285 94 7 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) THE APPARATUS OF IMPUNITY? Human rights violations and the Northern Ireland conflict: a narrative of official limitations on post-Agreement investigative mechanisms Committee on the Administration of Justice January 2015 The Apparatus of Impunity? Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ) Recent comments from key Council of Europe and UN human rights bodies in relation to existing mechanisms investigating the conflict in Northern Ireland: The absence of any plausible explanation for the failure to collect key evidence at the time when this was possible, and for attempts to even obstruct this process, should be treated with particular vigilance. -

NORTHERN IRELAND Continued Abuses by All Sides

March 1994 Vol. 6, No. 4 NORTHERN IRELAND Continued Abuses by all Sides CONTENTS Emergency laws ............................................................................................................................................................ 2 Death connected with "The Troubles" ....................................................................................................................... 2 Investigation of the use of lethal force by security forces and prosecution of those responsible for killings ............................................................................................... 3 Collusion between security forces and loyalist paramilitaries ................................................................................... 5 Coroners' inquests ........................................................................................................................................................ 5 Plastic bullets ................................................................................................................................................................ 6 Ill-treatment in detention ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Right to a fair trial ......................................................................................................................................................... 7 Harassment by security forces .................................................................................................................................... -

References Ready for Transfer to WORD

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: McIntosh, S. (2016). Open justice and investigations into deaths at the hands of the police, or in police or prison custody. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City, University of London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/15340/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Open Justice and Investigations into Deaths at the Hands of the Police, or in Police or Prison Custody By Sam McIntosh PhD Candidate CITY UNIVERSITY, LONDON LAW SCHOOL FEBRUARY 2016 i CONTENTS Table of Contents ii Table of Cases (England and Wales) x Table of Cases (ECtHR and ECmHR) xii Table of Cases (other Jurisdictions) xiv Table of Statutes and Bills xvi Table of Statutory Instruments -

The Hourly Rate

THEWRIT ISSUE 198 JANUARY - MARCH 2009 THE JOURNAL OF THE LAW SOCIETY OF NORTHERN IRELAND THIS MONTH: The Hourly Rate Journal of the LSNI January to March 2009 03 INDEX JAN-MARCH 2009 PUBLISHERS The Law Society of Northern Ireland 40 Linenhall Street BELFAST THEWRIT BT2 8BA Tel: 028 9023 1614 Fax: 028 9023 2606 ISSUE 198 JANUARY - MARCH 2009 THE JOURNAL OF THE LAW SOCIETY OF NORTHERN IRELAND E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.lawsoc-ni.org EDITOR Alan Hunter [email protected] DEPUTY EDITORS Heather Semple [email protected] Peter O’Brien [email protected] ADVERTISING MANAGER Karen Irwin [email protected] THIS MONTH: DESIGN The Walkers Communications Ltd Hourly www.walkercommunications.co.uk Rate DISCLAIMER The Law Society of Northern Ireland accepts no responsibility for the accuracy of contributed articles or statements appearing in this magazine and any views or opinions expressed are not necessarily those 04 Cover Story: of the Law Society’s Council, save where otherwise indicated. No responsibility for loss or distress occasioned to any person acting or refraining from Taxation of costs acting as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by the authors, contributors, editor or publishers. The editor reserves the right to and the hourly rate make publishing decisions on any advertisement or editorial article submitted to this magazine and to refuse publication or to edit any editorial material as seems appropriate to the editor. The Law Society 08 Responding to policy and law reform initiatives of Northern Ireland does not endorse any goods or services advertised, nor any claims or representations made in any advertisement in this magazine. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The crisis of civil-military relations in Mexico during the war against drugs: comparative reections on accountability and legal reform in the modern democratic era RAMIREZ-MENDOZA, SERGIO,LUIS How to cite: RAMIREZ-MENDOZA, SERGIO,LUIS (2017) The crisis of civil-military relations in Mexico during the war against drugs: comparative reections on accountability and legal reform in the modern democratic era, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/11977/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Sergio Luis Ramirez Mendoza The crisis of civil-military relations in Mexico during the war against drugs: comparative reflections on accountability and legal reform in the modern democratic era This research is focused on the current crisis that is taking place between Mexico’s civil society and the armed forces in the context of the “war against drugs”. -

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard)

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard) Friday 6 July 2012 Volume 76, No WA3 This publication contains the written answers to questions tabled by Members. The content of the responses is as received at the time from the relevant Minister or representative of the Assembly Commission and has not been subject to the official reporting process or changed in any way. Contents Written Answers to Questions Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister ............................................................... WA 299 Department of Agriculture and Rural Development .................................................................. WA 303 Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure ................................................................................ WA 335 Department of Education ...................................................................................................... WA 341 Department for Employment and Learning .............................................................................. WA 376 Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment .................................................................... WA 383 Department of Finance and Personnel ................................................................................... WA 392 Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety ......................................................... WA 394 Department of Justice .......................................................................................................... WA 399 Department -

The UK and the European Court of Human Rights

Equality and Human Rights Commission Research report 83 The UK and the European Court of Human Rights Alice Donald, Jane Gordon and Philip Leach Human Rights and Social Justice Research Institute London Metropolitan University The UK and the European Court of Human Rights Alice Donald, Jane Gordon and Philip Leach Human Rights and Social Justice Research Institute London Metropolitan University © Equality and Human Rights Commission 2012 First published Spring 2012 ISBN 978 1 84206 434 4 Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report Series The Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report Series publishes research carried out for the Commission by commissioned researchers. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Commission. The Commission is publishing the report as a contribution to discussion and debate. Please contact the Research Team for further information about other Commission research reports, or visit our website: Research Team Equality and Human Rights Commission Arndale House The Arndale Centre Manchester M4 3AQ Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0161 829 8500 Website: www.equalityhumanrights.com You can download a copy of this report as a PDF from our website: http://www.equalityhumanrights.com/ If you require this publication in an alternative format, please contact the Communications Team to discuss your needs at: [email protected] Contents Page Tables i Acknowledgments ii Abbreviations iii Executive summary v 1. Introduction 1 1.1 Aims of the report 1 1.2 Context of the report 1 1.3 Methodology 3 1.4 Scope of the report 4 1.5 Guide to the report 5 2. -

1 Appendix Table of Contents Songs

1 Appendix Table of Contents Songs and Classifications 1 Selective Timeline 2 Belfast and Derry Religious Demographics 6 “The Men Behind The Wire” 7 Belfast Murals 8 Songs and Classifications When working with these songs, I divided them into four categories - Aggressive/Militant Support for the conflict (along with which side it seemed to support), Passive/Non-violent Support (also with which side), Aggressive/Militant Opposition, and Passive/Non-violent Opposition. While some of these divisions were fairly clear, others were based on personal interpretation. As such, this is a list of the music I looked at and which category I placed them in, both for easy reference and later research. AS - Aggressive Support PS - Passive Support AO - Aggressive Opposition PO - Passive Opposition N/R - Nationalist/Republican U/L - Unionist/Loyalist Unknown Date “The Sash My Father Wore” - Unknown Artist - Unknown Date - PS-U “Daddy’s Uniform” - Unknown Artist - Unknown Date - AS-L (I couldn’t find a solid date for either of these, but because the former may be from a nineteenth-century tune and the latter seems to be post-WWII in origin, I discussed them in the 1960s-70s category because presumably they were already known by that point.) 1960s-1970s “Only Her Rivers Run Free” - Mickey MacConnell - 1965 - PS-N “Four Green Fields” - Tommy Makem - 1967 - PS-N “The Men Behind the Wire” - Paddy McGuigan - 1971 - PS-N “The Men Behind the Wire” - Unknown - 1972 - PS-U “Give Ireland Back to the Irish” - Paul McCartney - 1972 - PO “Go On Home, British Soldiers” -

The Murals of Northern Ireland and the Management of History

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Faculty Publications and Research Scripps Faculty Scholarship 1-1-2011 The Art of Memory: The urM als of Northern Ireland and the Management of History Tony Crowley Scripps College Recommended Citation Crowley, Tony. "The Art of Memory: The urM als of Northern Ireland and the Management of History." Field Day Review 7 (2011): 22-49. Print. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Faculty Publications and Research by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FIElD DAy REVIEw Fig. 1: West Belfast Taxi Tours. Divis St., Belfast, 2002. 22 1 Robert McLiam Wilson, Eureka Street (New York, 2007), 63–64 The Art of 2 ccdl.libraries.claremont. edu/col/mni/ (accessed 20 July 2011). Memory: The Murals of Northern Ireland and the Management of History Tony Crowley It was Povertyland. It was the land where the bad things happened … It was the land where they wrote things on the walls. Robert McLiam Wilson, Eureka Street1 Introduction The online archive Murals of Northern Ireland, held in Claremont Colleges Digital Library and covering the period from the late 1970s to the recent past,2 shows how the nature and function of murals in Northern Ireland have changed. In Derry and Belfast, they are the focal FielD DAy Review 7 2011 23 FIElD DAy REVIEw Fig. 2: Islandbawn Street, Belfast, 1983. point of a tourist trail that has been the locally based organizations provide 3 http://www. -

Statewatch Bulletin Vol 4 No 3 May – June 1994

Statewatch bulletin More and more asylum-seekers are being sent from the country where they claim asylum to a country of transit deemed`safe', a number of those countries Vol 4 no 3 May – June 1994 turn out not to be so safe. Austria has been condemned as unsafe by the UN High IMMIGRATION Commissioner for Refugees, in a recent report which says there is no guarantee that asylum-seekers will Refugees = terrorists be given the right to apply for asylum there. Refugee agencies say that Austria has sent back As part of its efforts to define the world as `safe' for asylum-seekers to Iran, Iraq and Syria. Switzerland's refugees (as opposed to trying to make it safe) the policies have been condemned by the UN Home Office has recently devised some new Committee against Torture, which is not satisfied formulae. with the criteria governing the inclusion of countries The Indian government, and in particular the Punjab on the `safe' list; Switzerland deems all central regional government, has come in for a lot of severe European states safe, as well as India and Senegal criticism for human rights abuses by the security and, of course, Sri Lanka, where up to 11,000 forces and police. An estimated 22,000 Sikhs are in rejected asylum-seekers are to be returned. The UN prison, and another 50,000 have been killed in the Committee fears that asylum-seekers could be sent last decade, many in false `encounters' with the back to countries where they run the risk of being security forces (where they are captured, shot and tortured. -

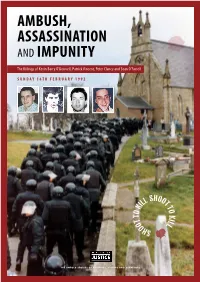

Clonoe-Report-Lres

AMBUSH, ASSASSINATION AND IMPUNITY The Killings of Kevin Barry O’Donnell, Patrick Vincent, Peter Clancy and Sean O’Farrell SUNDAY 16TH FEBRUARY 1992 L SHOOT IL T O K O K T I L T L O O H S THE UNTOLD STORIES OF RELATIVES, VICTIMS AND SURVIVORS AMBUSH, ASSASSINATION AND IMPUNITY The Killings of Peter Clancy, Sean Farrell, Kevin Barry O’Donnell and Patrick Vincent Relatives for Justice 39 Glen Road Belfast BT11 8BB Tel: 028 9062 7171 Fax: 028 9060 5558 Email: [email protected] www.relativesforjustice.com Relatives for Justice 42 Irish Street Dungannon Co. Tyrone BT70 1DQ Tel: 028 8775 1697 Email: [email protected] RELATIVES FOR JUSTICE Contents Introduction 3 The Harassment of Kevin Barry O’Donnell and Sean O’Farrell 4 Clonoe 16th February 1992 4 The Funerals 8 Pre-Meditated and Pre-Planned 10 Belfast High Court finds shooting “unjustified” 12 Who sanctioned the killings in Clonoe? 14 Shoot-To-Kill Policy 16 International Intervention 22 1 HUMAN RIGhts New opportunities 23 International standards 23 Families Developing Article 2 Standards 25 Inquests 25 The Right to Legal Representation 27 Conclusion 27 Key Points 28 The Families make the Following Calls 29 Biographies of Deceased 30 Acknowledgements 32 PETER CLANCY, SEAN FARRELL, KEVIN BARRY O’DONNELL, PATRICK VINCENT PETER CLANCY, SEAN FARRELL, KEVIN BARRY O’DONNELL, PATRICK VINCENT PETER CLANCY, SEAN FARRELL, KEVIN BARRY O’DONNELL, PATRICK VINCENT PETER CLANCY, SEAN FARRELL, KEVIN BARRY O’DONNELL, PATRICK VINCENT PETER CLANCY, SEAN FARRELL, KEVIN BARRY O’DONNELL,