Counts of Frontal Air Bag Related Fatalities and Seriously Injured Persons

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diagnoses to Include in the Problem List Whenever Applicable

Diagnoses to include in the problem list whenever applicable Tips: 1. Always say acute or open when applicable 2. Always relate to the original trauma 3. Always include acid-base abnormalities, AKI due to ATN, sodium/osmolality abnormalities 4. Address in the plan of your note 5. Do NOT say possible, potential, likely… Coders can only use a real diagnosis. Make a real diagnosis. Neurological/Psych: Head: 1. Skull fracture of vault – open vs closed 2. Basilar skull fracture 3. Facial fractures 4. Nerve injury____________ 5. LOC – include duration (max duration needed is >24 hrs) and whether they returned to neurological baseline 6. Concussion with or without return to baseline consciousness 7. DAI/severe concussion with or without return to baseline consciousness 8. Type of traumatic brain injury (hemorrhages and contusions) – include size a. Tiny = <0.6 cm b. Small/moderate = 0.6-1 cm c. Large/extensive = >1 cm 9. Cerebral contusion/hemorrhage 10. Cerebral edema 11. Brainstem compression 12. Anoxic brain injury 13. Seizures 14. Brain death Spine: 1. Cervical spine fracture with (complete or incomplete) or without cord injury 2. Thoracic spine fracture with (complete or incomplete) or without cord injury 3. Lumbar spine fracture with (complete or incomplete) or without cord injury 4. Cord syndromes: central, anterior, or Brown-Sequard 5. Paraplegia or quadriplegia (any deficit in the upper extremity is consistent with quadriplegia) Cardiovascular: 1. Acute systolic heart failure 40 2. Acute diastolic heart failure 3. Chronic systolic heart failure 4. Chronic diastolic heart failure 5. Combined heart failure 6. Cardiac injury or vascular injuries 7. -

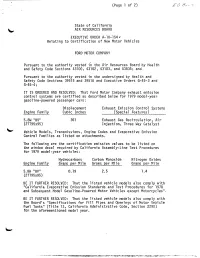

Page 1 Of.Tif

(Page 1 of 2) EO BEST State of California AIR RESOURCES BOARD EXECUTIVE ORDER A-10-154 . Relating to Certification of New Motor Vehicles FORD MOTOR COMPANY Pursuant to the authority vested in the Air Resources Board by Health and Safety Code Sections 43100, 43102, 43103, and 43835; and Pursuant to the authority vested in the undersigned by Health and Safety Code Sections 39515 and 39516 and Executive Orders G-45-3 and G-45-4; IT IS ORDERED AND RESOLVED: That Ford Motor Company exhaust emission control systems are certified as described below for 1979 model-year gasoline-powered passenger cars : Displacement Exhaust Emission Control Systems Engine Family Cubic Inches (Special Features 5. 8W "BV" 351 Exhaust Gas Recirculation, Air (2TT95x95) Injection, Three Way Catalyst Vehicle Models, Transmissions, Engine Codes and Evaporative Emission Control Families as listed on attachments. The following are the certification emission values to be listed on the window decal required by California Assembly-Line Test Procedures for 1979 model-year vehicles : Hydrocarbons Carbon Monoxide Nitrogen Oxides Engine Family Grams per Mile Grams per Mile Grams per Mile 5. 8W "BV" 0. 19 2.5 1.4 (2TT95x95) BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED: That the listed vehicle models also comply with "California Evaporative Emission Standards and Test Procedures for 1978 and Subsequent Model Gasoline-Powered Motor Vehicles except Motorcycles". BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED: That the listed vehicle models also comply with the Board's "Specifications for Fill Pipes and Openings of Motor Vehicle Fuel Tanks" (Title 13, California Administrative Code, Section 2290) for the aforementioned model year. -

Two Types of Delayed Post-Traumatic Intracerebral Hematoma

Two Types of Delayed Post-Traumatic Intracerebral Hematoma Takashi TSUBOKAWA Department of Neurological Surgery, Nihon University School of Medicine, Tokyo 173 Summary The findings of repeated CT scans, clinicalcourses and pathologicalstudies in 28 cases of delayed post-traumatic intracerebral hematoma were studied retrospectivelyto elucidate the mechanism of bleeding and to establish adequate treatment. Based on the results obtained, it became clear that there are two types of delayed hematoma. In 10 of the 28 cases, initial CT findings within 6 hours after head injury revealed cerebral contusion or hemorrhagic contusion, and spots of high density scattered in the low density zone gradually became confluent to form an irregularly shaped hematoma according to follow-up CT findings. This was termed "hematoma within a contusional area." In 15 of the 28 cases, initial CT findings within 6 hours after head injury revealed no abnormal density within the brain and the hematoma appeared suddenly 3 6 days after the injury. In eight of the 15 cases, emergency surgery was performed for the removal of epidural or subdural hematoma. This type of hematoma is termed "contusional hem atoma" and constitutes the second group. In three of the 28 cases, both types of hematoma were observed. Based on histological findings for the two types of delayed hematoma. The first group may be induced by an anoxic vasodilation mechanism (Evans et al.9)), while the second group may be derived from a different mechanism related to ishemic changes and the free radical reaction caused by the reflow phenomenon (Tsubokawa et al.14-16)1 It is important to establish correct diagnoses 1for delayed hematomas based on differences between follow-up findings of repeated CT and an initial CT performed within 6 hours after head injury since the operative indications and operative results for the two groups are different as indicated by our 28 cases. -

Management of the Head Injury Patient

Management of the Head Injury Patient William Schecter, MD Epidemilogy • 1.6 million head injury patients in the U.S. annually • 250,000 head injury hospital admissions annually • 60,000 deaths • 70-90,000 permanent disability • Estimated cost: $100 billion per year Causes of Brain Injury • Motor Vehicle Accidents • Falls • Anoxic Encephalopathy • Penetrating Trauma • Air Embolus after blast injury • Ischemia • Intracerebral hemorrhage from Htn/aneurysm • Infection • tumor Brain Injury • Primary Brain Injury • Secondary Brain Injury Primary Brain Injury • Focal Brain Injury – Skull Fracture – Epidural Hematoma – Subdural Hematoma – Subarachnoid Hemorrhage – Intracerebral Hematorma – Cerebral Contusion • Diffuse Axonal Injury Fracture at the Base of the Skull Battle’s Sign • Periorbital Hematoma • Battle’s Sign • CSF Rhinorhea • CSF Otorrhea • Hemotympanum • Possible cranial nerve palsy http://health.allrefer.com/pictures-images/ Fracture of maxillary sinus causing CSF Rhinorrhea battles-sign-behind-the-ear.html Skull Fractures Non-depressed vs Depressed Open vs Closed Linear vs Egg Shell Linear and Depressed Normal Depressed http://www.emedicine.com/med/topic2894.htm Temporal Bone Fracture http://www.vh.org/adult/provider/anatomy/ http://www.bartleby.com/107/illus510.html AnatomicVariants/Cardiovascular/Images0300/0386.html Epidural Hematoma http://www.chestjournal.org/cgi/content/full/122/2/699 http://www.bartleby.com/107/illus769.html Epidural Hematoma • Uncommon (<1% of all head injuries, 10% of post traumatic coma patients) • Located -

Blood Pressure Control in Neurological ICU Patients: What Is Too High and What Is Too Low? Gulrukh Zaidi*,1, Astha Chichra1, Michael Weitzen2 and Mangala Narasimhan1

Send Orders for Reprints to [email protected] 46 The Open Critical Care Medicine Journal, 2013, 6, (Suppl 1: M3) 46-55 Open Access Blood Pressure Control in Neurological ICU Patients: What is Too High and What is Too Low? Gulrukh Zaidi*,1, Astha Chichra1, Michael Weitzen2 and Mangala Narasimhan1 1The Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine, The North Shore, Long-Island Jewish Health System, The Hofstra-North Shore LIJ School of Medicine, USA 2Department of Surgery, Phelps Memorial Hospital, USA Abstract: The optimal blood pressure (BP) management in critically ill patients with neurological emergencies in the intensive care unit poses several challenges. Both over and under correction of the blood pressure are associated with increased morbidity and mortality in this population. Target blood pressures and therapeutic management are based on guidelines including those from the American Stroke Association and the Joint National Committee guidelines. We review these recommendations and the current concepts of blood pressure management in neurological emergencies. A variety of therapeutic agents including nicardipine, labetalol, nitroprusside are used for blood pressure management in patients with ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes. Currently, the role of inducing hypertension remains unclear. Hypertensive crises include hypertensive urgencies where elevated blood pressures are seen without end organ damage and can usually be managed by oral agents, and hypertensive emergencies where end organ damage is present and requires immediate treatment with intravenous drugs. Keywords: Ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, hypertension, hypotension, thrombolytic therapy, hypertensive urgency and emergency, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome. INTRODUCTION However, an understanding of cerebral autoregulation is essential prior to discussing the management of either hyper The optimization of blood pressure in patients admitted or hypotension in these patients. -

Sports-Related Concussions: Diagnosis, Complications, and Current Management Strategies

NEUROSURGICAL FOCUS Neurosurg Focus 40 (4):E5, 2016 Sports-related concussions: diagnosis, complications, and current management strategies Jonathan G. Hobbs, MD,1 Jacob S. Young, BS,1 and Julian E. Bailes, MD2 1Department of Surgery, Section of Neurosurgery, The University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, Chicago; and 2Department of Neurosurgery, NorthShore University HealthSystem, The University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, Evanston, Illinois Sports-related concussions (SRCs) are traumatic events that affect up to 3.8 million athletes per year. The initial diag- nosis and management is often instituted on the field of play by coaches, athletic trainers, and team physicians. SRCs are usually transient episodes of neurological dysfunction following a traumatic impact, with most symptoms resolving in 7–10 days; however, a small percentage of patients will suffer protracted symptoms for years after the event and may develop chronic neurodegenerative disease. Rarely, SRCs are associated with complications, such as skull fractures, epidural or subdural hematomas, and edema requiring neurosurgical evaluation. Current standards of care are based on a paradigm of rest and gradual return to play, with decisions driven by subjective and objective information gleaned from a detailed history and physical examination. Advanced imaging techniques such as functional MRI, and detailed understanding of the complex pathophysiological process underlying SRCs and how they affect the athletes acutely and long-term, may change the way physicians treat athletes who suffer a concussion. It is hoped that these advances will allow a more accurate assessment of when an athlete is truly safe to return to play, decreasing the risk of secondary impact injuries, and provide avenues for therapeutic strategies targeting the complex biochemical cascade that results from a traumatic injury to the brain. -

Anesthetic Management of a Patient with Obstructive Prosthetic Aortic Valve Dysfunction -A Case Report

Korean J Anesthesiol 2014 February 66(2): 160-163 Case Report http://dx.doi.org/10.4097/kjae.2014.66.2.160 Anesthetic management of a patient with obstructive prosthetic aortic valve dysfunction -a case report- Bo Ra Lee, Jeong-Rim Lee, and Min Soo Kim Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Anesthesia and Pain Research Institute, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea We present a 55-year-old female patient who underwent burr-hole drainage due to chronic subdural hematoma, with obstructive prosthetic aortic valve dysfunction. Anesthetic management of a patient with severe obstructive prosthetic aortic valve dysfunction can be challenging. Similar considerations should be given to patients with aortic stenosis with an additional emphasis on thrombotic complication due to discontinuation of anticoagulation, which may further jeop- ardize the valve dysfunction. This case emphasizes the importance of a comprehensive understanding of the etiology and hemodynamic consequences of obstructive prosthetic valve dysfunction and the adequacy of anticoagulation for patients undergoing noncardiac surgery even after a successful valve replacement. (Korean J Anesthesiol 2014; 66: 160-163) Key Words: Aortic valve stenosis, Echocardiography, Heart valve prosthesis, Thrombosis. Even after a successful heart valve replacement without pros- valves, discontinuation of anticoagulation for other medico- thetic valve malfunction, obstructive prosthetic valvular dys- surgical conditions may further aggravate the pressure imposed function (PVD) may occur due to prosthesis-patient mismatch on the LV due to thrombus formation [4]. We herein report a (PPM), pannus formation, and thrombus formation [1]. Consid- case of a patient with obstructive PVD after mechanical aortic ering the relatively narrow anatomic feature of the left ventricu- valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis, requiring burr-hole lar (LV) outflow tract, the aortic valve is more prone to develop drainage for a subdural hematoma. -

En 13-Correlation Between.P65

Morgado FL et al. CorrelaçãoARTIGO entre ORIGINAL a ECG e •achados ORIGINAL de imagem ARTICLE de TC no TCE Correlação entre a escala de coma de Glasgow e os achados de imagem de tomografia computadorizada em pacientes vítimas de traumatismo cranioencefálico* Correlation between the Glasgow Coma Scale and computed tomography imaging findings in patients with traumatic brain injury Fabiana Lenharo Morgado1, Luiz Antônio Rossi2 Resumo Objetivo: Determinar a correlação da escala de coma de Glasgow, fatores causais e de risco, idade, sexo e intubação orotraqueal com os achados tomográficos em pacientes com traumatismo cranioencefálico. Materiais e Métodos: Foi realizado estudo transversal prospectivo de 102 pacientes, atendidos nas primeiras 12 horas, os quais receberam pontuação segundo a escala de coma de Glasgow e foram submetidos a exame tomográfico. Resultados: A idade média dos pacientes foi de 37,77 ± 18,69 anos, com predomínio do sexo masculino (80,4%). As causas foram: acidente automobilístico (52,9%), queda de outro nível (20,6%), atropelamento (10,8%), queda ao solo ou do mesmo nível (7,8%) e agressão (6,9%). No presente estudo, 82,4% dos pacientes apresentaram traumatismo cranioencefálico de classificação leve, 2,0% moderado e 15,6% grave. Foram observadas alterações tomográficas (hematoma subgaleal, fraturas ósseas da calota craniana, hemorragia subaracnoidea, contusão cerebral, coleção sanguínea extra-axial, edema cerebral difuso) em 79,42% dos pacientes. Os achados tomográficos de trauma craniano grave ocorreram em maior número em pacientes acima de 50 anos (93,7%), e neste grupo todos necessitaram de intubação orotraqueal. Con- clusão: Houve significância estatística entre a escala de coma de Glasgow, idade acima de 50 anos (p < 0,0001), necessidade de intubação orotraqueal (p < 0,0001) e os achados tomográficos. -

Traumatic Brain Injury(Tbi)

TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY(TBI) B.K NANDA, LECTURER(PHYSIOTHERAPY) S. K. HALDAR, SR. OCCUPATIONAL THERAPIST CUM JR. LECTURER What is Traumatic Brain injury? Traumatic brain injury is defined as damage to the brain resulting from external mechanical force, such as rapid acceleration or deceleration impact, blast waves, or penetration by a projectile, leading to temporary or permanent impairment of brain function. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) has a dramatic impact on the health of the nation: it accounts for 15–20% of deaths in people aged 5–35 yr old, and is responsible for 1% of all adult deaths. TBI is a major cause of death and disability worldwide, especially in children and young adults. Males sustain traumatic brain injuries more frequently than do females. Approximately 1.4 million people in the UK suffer a head injury every year, resulting in nearly 150 000 hospital admissions per year. Of these, approximately 3500 patients require admission to ICU. The overall mortality in severe TBI, defined as a post-resuscitation Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) ≤8, is 23%. In addition to the high mortality, approximately 60% of survivors have significant ongoing deficits including cognitive competency, major activity, and leisure and recreation. This has a severe financial, emotional, and social impact on survivors left with lifelong disability and on their families. It is well established that the major determinant of outcome from TBI is the severity of the primary injury, which is irreversible. However, secondary injury, primarily cerebral ischaemia, occurring in the post-injury phase, may be due to intracranial hypertension, systemic hypotension, hypoxia, hyperpyrexia, hypocapnia and hypoglycaemia, all of which have been shown to independently worsen survival after TBI. -

Anticoagulant-Related Subdural Hematoma in Patients with Mechanical Heart Valves

Neurology Asia 2005; 10 : 13 – 19 ORIGINAL ARTICLES Anticoagulant-related subdural hematoma in patients with mechanical heart valves GVS Chowdary MD DM, T Jaishree Naryanan MD PhD, *P Syed Ameer Basha MBBS MCh, *TVRK Murthy MBBS MCh, JMK Murthy MD DM Department of Neurology and *Neurosurgery, The Institute of Neurological Sciences, CARE Hospital, Nampally, Hyderabad, India Abstract Introduction: There is uncertainty on the timing of surgery in patients with anticoagulant-related subdural hematoma (SDH) and also on the timing of reintroduction of anticoagulants. Methods: We retrospectively analyzed records of 7 patients with mechanical heart valves and anticoagulant-related SDH. Results: Of the 7 patients, 6 (83%) survived to discharge with good functional outcome, modified Rankin Scale 0-1. Reversal of anticoagulation (INR < 1.4) could be achieved in 5 patients. Three patients with minimal deficit and no CT evidence of midline shifts were managed non-surgically. Three patients had surgical evacuation, 2 with acute SDH and midline shift and one patient with bilateral subacute SDH and no midline shift. The mean duration of anticoagulation withholding was 20.3 days (range 8-28). None had thrombolic events while off anticoagulation. Five patients were restarted on acenocumarol/warfarin when follow-up cranial CT showed decrease or resolution of SDH. High risk for thromboembolism was the indication for early anticoagulation in the patient with mitral position of the prosthesis and atrial fibrillation. One of the patient with subacute SDH who had post surgical residual SDH and echocardiographic evidence of valve dysfunction was initially started on unfractionated heparin followed by nadroparin calcium and subsequently on acenocumarol. -

Determination of Prognostic Factors in Cerebral Contusions Serebral Kontüzyonlarda Prognostik Faktörlerin Belirlenmesi

ORIGINAL RESEARCH Bagcilar Med Bull 2019;4(3):78-85 DO I: 10.4274/BMB.galenos.2019.08.013 Determination of Prognostic Factors in Cerebral Contusions Serebral Kontüzyonlarda Prognostik Faktörlerin Belirlenmesi Neşe Keser1, Murat Servan Döşoğlu2 1University of Health Sciences, Fatih Sultan Mehmet Training and Research Hospital, Clinic of Neurosurgery, İstanbul, Turkey 2İçerenköy Bayındır Hospital, Clinic of Neurosurgery, İstanbul, Turkey Abstract Öz Objective: Cerebral contusion (CC) is vital because it is one of the Amaç: Kontüzyo serebri, en sık karşılaşılan travmatik beyin yaralanması most common traumatic brain injury (TBI) types and can lead to lifelong olması ve ömür boyu süren fiziksel, bilişsel ve psikolojik bozukluklara physical, cognitive, and psychological disorders. As with all other types of yol açabilmesi nedeniyle önem taşımaktadır. Diğer tüm kraniyoserebral craniocerebral trauma, the correlation of prognosis with specific criteria travma tiplerinde olduğu gibi kontüzyon serebride de prognozun belli in CC can provide more effective treatment methods with objective kriterlere bağlanması objektif yaklaşımlarla vakit geçirmeden daha efektif approaches. tedavi yöntemlerinin belirlenmesini sağlayabilir. Method: The results of 105 patients who were hospitalized in the Yöntem: Acil poliklinikte kontüzyon serebri saptanılarak yatırılan, emergency clinic with the diagnosis of CC and whose lesion did not lezyonu cerrahi müdahale gerektirmeyen 105 olgu araştırıldı. Demografik require surgical intervention were evaluated. The demographic variables, değişkenler, Glasgow koma skalası (GKS) skoru, radyografik bulgular, Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score, radiographic findings, coexisting eşlik eden travmalar, kraniyal bilgisayarlı tomografide (BT) saptanılan traumas and, type, number, and the midline shift of the contusions kontüzyonların tipi, sayısı, ile oluşturduğu orta hat şiftine göre sonuçları detected in computerized tomography (CT) were evaluated as a guide in bir aylık dönemde prognoz tayininde yol gösterici olarak değerlendirildi. -

Acute Subdural Hematoma in Patients on Oral Anticoagulant Therapy: Management and Outcome

NEUROSURGICAL FOCUS Neurosurg Focus 43 (5):E12, 2017 Acute subdural hematoma in patients on oral anticoagulant therapy: management and outcome Sae-Yeon Won, MD, Daniel Dubinski, MD, MSc, Markus Bruder, MD, Adriano Cattani, MD, PhD, Volker Seifert, MD, PhD, and Juergen Konczalla, MD Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital, Goethe-University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany OBJECTIVE Isolated acute subdural hematoma (aSDH) is increasing in older populations and so is the use of oral anticoagulant therapy (OAT). The dramatic increase of OAT—with direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) as well as with conventional anticoagulants—is leading to changes in the care of patients who present with aSDH while receiving OAT. The purpose of this study was to determine the management and outcome of patients being treated with OAT at the time of aSDH presentation. METHODS In this single-center, retrospective study, the authors analyzed 116 consecutive cases involving patients with aSDH treated from January 2007 to June 2016. The following parameters were assessed: patient characteristics, admission status, anticoagulation status, perioperative management, comorbidities, clinical course, and outcome as determined at discharge and through 6 months of follow-up. Oral anticoagulants were classified as thrombocyte inhibi- tors, vitamin K antagonists, and DOACs. Patients were stratified based on which type of medication they were taking, and subgroup analyses were performed. Predictors of unfavorable outcome at discharge and follow-up were identified. RESULTS Of 116 patients, 74 (64%) had been following an OAT regimen at presentation with aSDH. The patients who were taking oral anticoagulants (OAT group) were significantly older (OR 12.5), more often comatose 24 hours postop- eratively (OR 2.4), and more often had ≥ 4 comorbidities (OR 3.2) than patients who were not taking oral anticoagulants (no-OAT group).