Ndance YOUR STYLE!"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Customer Order Form

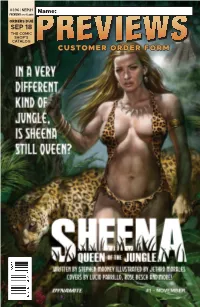

#396 | SEP21 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE SEP 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Sep21 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:51 AM GTM_Previews_ROF.indd 1 8/5/2021 8:54:18 AM PREMIER COMICS NEWBURN #1 IMAGE COMICS 34 A THING CALLED TRUTH #1 IMAGE COMICS 38 JOY OPERATIONS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 84 HELLBOY: THE BONES OF GIANTS #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 86 SONIC THE HEDGEHOG: IMPOSTER SYNDROME #1 IDW PUBLISHING 114 SHEENA, QUEEN OF THE JUNGLE #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 132 POWER RANGERS UNIVERSE #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 184 HULK #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-4 Sep21 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 8/5/2021 10:52:11 AM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Guillem March’s Laura #1 l ABLAZE The Heathens #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Fathom: The Core #1 l ASPEN COMICS Watch Dogs: Legion #1 l BEHEMOTH ENTERTAINMENT 1 Tuki Volume 1 GN l CARTOON BOOKS Mutiny Magazine #1 l FAIRSQUARE COMICS Lure HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS 1 The Overstreet Guide to Lost Universes SC/HC l GEMSTONE PUBLISHING Carbon & Silicon l MAGNETIC PRESS Petrograd TP l ONI PRESS Dreadnoughts: Breaking Ground TP l REBELLION / 2000AD Doctor Who: Empire of the Wolf #1 l TITAN COMICS Blade Runner 2029 #9 l TITAN COMICS The Man Who Shot Chris Kyle: An American Legend HC l TITAN COMICS Star Trek Explorer Magazine #1 l TITAN COMICS John Severin: Two-Fisted Comic Book Artist HC l TWOMORROWS PUBLISHING The Harbinger #2 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT Lunar Room #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 My Hero Academia: Ultra Analysis Character Guide SC l VIZ MEDIA Aidalro Illustrations: Toilet-Bound Hanako Kun Ark Book SC l YEN PRESS Rent-A-(Really Shy!)-Girlfriend Volume 1 GN l KODANSHA COMICS Lupin III (Lupin The 3rd): Greatest Heists--The Classic Manga Collection HC l SEVEN SEAS ENTERTAINMENT APPAREL 2 Halloween: “Can’t Kill the Boogeyman” T-Shirt l HORROR Trese Vol. -

Released 19Th August 2020 BOOM!

Released 19th August 2020 BOOM! STUDIOS JAN201335 ANGEL SEASON 11 LIBRARY ED HC APR201364 FAITHLESS II #3 CVR A LLOVET APR201365 FAITHLESS II #3 CVR B EROTICA CONNECTING VAR JUN200787 FIREFLY #19 CVR A MAIN ASPINALL JUN200788 FIREFLY #19 CVR B KAMBADAIS VAR FEB201290 GO GO POWER RANGERS TP VOL 07 APR201373 JIM HENSON DARK CRYSTAL AGE RESISTANCE #10 CVR A FINDEN APR201374 JIM HENSON DARK CRYSTAL AGE RESISTANCE #10 CVR B MATTHEWS CO APR201371 ONCE & FUTURE #10 FEB201340 OVER GARDEN WALL SOULFUL SYMPHONIES TP JUN200764 POWER RANGERS DRAKKON NEW DAWN #1 CVR A MAIN SECRET JUN200767 POWER RANGERS DRAKKON NEW DAWN #1 FOIL VAR JUN208619 POWER RANGERS RANGER SLAYER #1 (2ND PTG) MAR201359 QUOTABLE GIANT DAYS GN JUN208620 SOMETHING IS KILLING CHILDREN #7 (2ND PTG) DARK HORSE COMICS APR200392 ART OF DRAGON PRINCE HC JAN200399 CYBERPUNK 2077 KITSCH PUZZLE JAN200400 CYBERPUNK 2077 NEOKITSCH PUZZLE JUN200310 DRAGON AGE BLUE WRAITH HC DC COMICS MAR200619 BATMAN BY GRANT MORRISON OMNIBUS HC VOL 03 OCT190663 GREEN ARROW LONGBOW HUNTERS OMNIBUS HC VOL 01 DYNAMITE APR201139 BETTIE PAGE #1 KANO LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201140 BETTIE PAGE #1 LINSNER LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201138 BETTIE PAGE #1 YOON LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201266 GEORGE RR MARTIN A CLASH OF KINGS #6 CVR A MILLER APR201267 GEORGE RR MARTIN A CLASH OF KINGS #6 CVR B RUBI APR201154 GREEN HORNET #1 JOHNSON LTD VIRGIN VAR APR201153 GREEN HORNET #1 WEEKS LTD VIRGIN VAR MAR201221 JAMES BOND #6 RICHARDSON LTD VIRGIN CVR MAR201231 KILLING RED SONJA #3 CVR A WARD MAR201232 KILLING RED SONJA #3 CVR B GEDEON HOMAGE APR201283 -

Your Guide to Understanding and Enjoying Powvwows

Indian Education for All Your Guide to Understanding and Enjoying Pow Wows Thanks to: Murton McCluskey, Ed.D. Revised January 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ...................................................................... 1 History of the Pow Wow ............................................... 2-3 The Pow Wow Committee ............................................ 4 Head Staff ............................................................. 4 Judges and Scoring................................................ 4-6 Contest Rules and Regulations ................................... 7 Singers..................................................................... 7 Dancers................................................................... 8 The Grand Entry................................................... 8 Pow Wow Participants.......................................... 9 The Announcer(s) ................................................ 9 Arena Director....................................................... 9 Head Dancers......................................................... 9 The Drum, Songs and Singers..................................... 10 The Drum...............................................................10 Singing..................................................................... 10-11 The Flag Song........................................................ 12 The Honor Song.................................................... 12 The Trick Song.......................................................12 Dances and Dancers....................................................... -

Feb 18 Customer Order Form

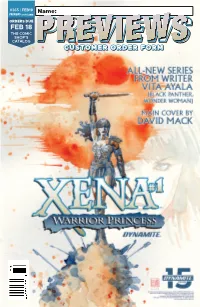

#365 | FEB19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE FEB 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Feb19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 1/10/2019 11:11:39 AM SAVE THE DATE! FREE COMICS FOR EVERYONE! Details @ www.freecomicbookday.com /freecomicbook @freecomicbook @freecomicbookday FCBD19_STD_comic size.indd 1 12/6/2018 12:40:26 PM ASCENDER #1 IMAGE COMICS LITTLE GIRLS OGN TP IMAGE COMICS AMERICAN GODS: THE MOMENT OF THE STORM #1 DARK HORSE COMICS SHE COULD FLY: THE LOST PILOT #1 DARK HORSE COMICS SIX DAYS HC DC COMICS/VERTIGO TEEN TITANS: RAVEN TP DC COMICS/DC INK TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA ASCENDER #1 TURTLES #93 STAR TREK: YEAR FIVE #1 IMAGE COMICS IDW PUBLISHING IDW PUBLISHING TEENAGE MUTANT NINJA TURTLES #93 IDW PUBLISHING THE WAR OF THE REALMS: JOURNEY INTO MYSTERY #1 MARVEL COMICS XENA: WARRIOR PRINCESS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT FAITHLESS #1 BOOM! STUDIOS SIX DAYS HC DC COMICS/VERTIGO THE WAR OF LITTLE GIRLS THE REALMS: OGN TP JOURNEY INTO IMAGE COMICS MYSTERY #1 MARVEL COMICS TEEN TITANS: RAVEN TP DC COMICS/DC INK AMERICAN GODS: THE MOMENT OF XENA: THE STORM #1 WARRIOR DARK HORSE COMICS PRINCESS #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT STAR TREK: YEAR FIVE #1 IDW PUBLISHING SHE COULD FLY: FAITHLESS #1 THE LOST PILOT #1 BOOM! STUDIOS DARK HORSE COMICS Feb19 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 1/10/2019 3:02:07 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Strangers In Paradise XXV Omnibus SC/HC l ABSTRACT STUDIOS The Replacer GN l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Mary Shelley: Monster Hunter #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Bronze Age Boogie #1 l AHOY COMICS Laurel & Hardy #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS Jughead the Hunger vs. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} the Authority Vol. 3 Earth

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The Authority Vol. 3 Earth Inferno and Other Stories by Mark Millar Authority Earth Inferno and Other Stories TPB (2002 DC/Wildstorm) comic books. Authority: Book 3 - 1st printing. Collects Authority (1999-2002 1st Series) #17-20 and Authority Annual (2000). Written by Mark Millar, Joe Casey, Warren Ellis, and Paul Jenkins. Art by Chris Weston, Frank Quitely, Cully Hamner, Georges Jeanty, Garry Leach, Trevor Scott, Karl Story, and Ray Snyder. WildStorm's wildest super-team returns in its third trade paperback - an anthology of outrageousness collecting some of the Authority's most unforgettable tales. Included is the much talked-about 'Earth Inferno' where the very planet we live on rebels against its inhabitants. Plus, THE AUTHORITY 2000 ANNUAL, and two tales from the WILDSTORM SUMMER SPECIAL: an introspective look at Jack Hawksmoor and a peek into the private life of the nanotech-enhanced Engineer. MATURE READERS Softcover, 160 pages, full color. Cover price $14.99. Authority: Book 3 - 2nd and later printings. Collects Authority (1999-2002 1st Series) #17-20 and Authority Annual (2000). Written by Mark Millar, Joe Casey, Warren Ellis, and Paul Jenkins. Art by Chris Weston, Frank Quitely, Cully Hamner, Georges Jeanty, Garry Leach, Trevor Scott, Karl Story, and Ray Snyder. WildStorm's wildest super-team returns in its third trade paperback - an anthology of outrageousness collecting some of the Authority's most unforgettable tales. Included is the much talked-about 'Earth Inferno' where the very planet we live on rebels against its inhabitants. Plus, THE AUTHORITY 2000 ANNUAL, and two tales from the WILDSTORM SUMMER SPECIAL: an introspective look at Jack Hawksmoor and a peek into the private life of the nanotech-enhanced Engineer. -

Download 2015 Manito Ahbee Festival Program

Celebrating 10 Years! Presented By FESTival pRogRaM SEpTEMbER 9-13 2015 MTS CENTRE WINNIPEG, MANITOBA, CANADA indigenousmusicawards.com manitoahbee.com NeedNeed fundingfunding forfor youryour nextnext project?project? ApplyApply for for FACTOR FACTOR fundingfunding atat www.factor.cawww.factor.ca to to get get help help for for tours, tours, sound sound recordings,recordings, andand music music videos. videos. We acknowledge the financial support We ofacknowledge Canada’s private the financial radio broadcasters. support of Canada’s private radio broadcasters. contentsTABLE OF About Manito Ahbee ............................................................................. 4 Welcome/Messages ............................................................................. 5 Board of Governors .............................................................................. 6 Greetings ............................................................................................... 8 Event Staff ............................................................................................ 12 Special Thanks .................................................................................... 23 Our Sponsors ...................................................................................... 32 Official Schedule .................................................................................. 34 IMA EvEnts >>> Red Carpet ........................................................................................... 25 The Hosts ........................................................................................... -

Customer Order Form

#376 | JAN20 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE JAN 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 Jan20 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 12/5/2019 4:59:33 PM Jan20 Ad DST Catwoman.indd 1 12/5/2019 3:43:15 PM PREMIER COMICS DECORUM #1 IMAGE COMICS 50 MIRKA ANDOLFO’S MERCY #1 IMAGE COMICS 54 X-RAY ROBOT #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 94 STARSHIP DOWN #1 DARK HORSE COMICS 96 ROBIN 80TH ANNIVERSARY 100-PAGE SPECTACULAR #1 DC COMICS DCP-1 STRANGE ADVENTURES #1 DC COMICS DCP-3 TRANSFORMERS VS. TERMINATOR #1 IDW PUBLISHING 130 SONIC THE HEDGEHOG ANNUAL 2020 IDW PUBLISHING 137 SPIDER-WOMAN #1 MARVEL COMICS MP-8 KILLING RED SONJA #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT 168 KING OF NOWHERE #1 BOOM! STUDIOS 204 Jan20 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 12/5/2019 10:58:38 AM COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Vampire State Building HC l ABLAZE The Man Who Effed Up Time #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Second Coming Volume 1 TP l AHOY COMICS The Spirit 80th Anniversary Celebration TP l CLOVER PRESS Marvel: We Are Super Heroes HC l DK PUBLISHING CO FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS 1 Amazing Spider-Man: My Mighty Marvel First Book Board Book l ABRAMS APPLESEED Captain America: My Mighty Marvel First Book Board Book l ABRAMS APPLESEED Artemis and the Assassin #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS Billionaire Island #1 l AHOY COMICS Hatchet: Unstoppable Horror #1 l AMERICAN MYTHOLOGY PRODUCTIONS 1 Cayrel’s Ring HC l A WAVE BLUE WORLD INC Resistance #1 l ARTISTS WRITERS & ARTISANS INC Doctor Who: At Childhood’s End HC l BBC BOOKS Tarot: Witch of the Black Rose #121 l BROADSWORD COMICS Butcher Knight TP l CLOVER PRESS, LLC Dragon Hoops HC l :01 FIRST SECOND The Fire Never Goes Out: A Memoir In Pictures HC l HARPER TEEN Hexagon #1 l IMPACT THEORY, LLC Star Trek: Kirk-Fu Manual HC l INSIGHT EDITIONS Dryad #1 l ONI PRESS The Mythics Vol. -

Music-Week-1998-10-2

PROFILE: The A&R: Having won A&R: It's quietly does industry is to gather the bidding war for it as Food slowly in salute to SIR SEAL, Warner Bros brings Scottish four - GEORGE MARTIN as has high hopes for his piece IDLEWILD to a he retires from music third album larger audience A life in music 10 Talent 15 Talent 17 FOR EVERYONE IN THE BUSINESS OF MUSIC 24 OCT"en music week Phillips set for Warner role by Robert Ashton not sat behind his desk since the contender for the job of running ing directorJeff Golembo has Nick Phillipsis expected to be beginning of the month. the combined PolyGram/Universal taken control of the company on a installed as Rob Dickins' succes- The exact circumstances of his UK operation, a post that is now day-to-daybasis. Onesenior sor at Warner Music following his departure still remain a source of set to be assumed by Kennedy. It source says no immediate sudden departure last week from speculation. Universal refused to is understood that legal discus- changes are expected at Universal the post of managing director at elaborate on a statement issued sions over the nature of Phillips's this side of Christmas, although Universal Music. on Thursday saying:"Itiswith contract with Universal have taken thesituationislikelytobe Hisexit was confirmedat a regret that we announce that Nick place in recent weeks. addressed early in the New Year. meeting attended by senior staff Phillipshas decided toleave Phillips was one of two top Phillips began his career in the atUniversal'sMandeville Place Universal Music (UK). -

Prison Magazine List Texas

Texas Prison Approved Magazines March 2020 ReqDate Publication MoDayYr Volume Number 2/1/2008 0:00 N74 Winter 2008 N13 8/26/2016 0:00 Teoria Del Mim Inviernode 1996 N1 5/19/2015 0:00 '68 Bad Sign One Shot 04/15 11/13/2013 0:00 '68 Hallowed Ground 11/13 1/14/2015 0:00 '68 Homefront 12/14 N4 12/19/2014 0:00 '68 Homefront 11/14 N3 10/9/2014 0:00 '68 Homefront 09/14 N1 11/26/2014 0:00 '68 Homefront 10/14 N2 8/18/2014 0:00 '68 Rule of War 07/14 N4 4/30/2014 0:00 '68 Rule of War 04/14 N1 7/10/2014 0:00 '68 Rule of War 05/14 N2 8/26/2014 0:00 '68 V1: Better Run Through the Jungle 2013 V1 8/26/2014 0:00 '68 V2: Scars 2013 V2 4/16/2015 0:00 '68: Jungle Jim: Guts n' Glory One-shot 03/15 2/19/2016 0:00 '68: Last Rites 01/16 N4 8/25/2015 0:00 '68: Last Rites 07/15 N1 10/21/2015 0:00 '68: Last Rites 09/15 N2 4/14/2008 0:00 ( 05/08 V12 N5 N125 1/23/2008 0:00 - voice N78 4/9/2009 0:00 0-60 Winter 2009 7/1/2010 0:00 0-60F Summer 2010 2/20/2009 0:00 002 Houston 02/09 V11 V122 2/20/2009 0:00 002 Houston 01/09 V11 V121 4/12/2012 0:00 002 Houston 01/12 V14 N157 4/19/2013 0:00 002 Houston 04/13 V15 N172 4/12/2012 0:00 002 Houston 02/12 V14 N158 10/29/2010 0:00 51 12/08 N17 7/6/2009 0:00 9 09/09 V38 N9 9/28/2017 0:00 1 World (Hip Hop Underground Magazine) 2017/2018 N3 11/13/2014 0:00 1-800-Homeopathy Catalog 11/14 3/7/2012 0:00 10-4 03/12 V19 N9 9/26/2011 0:00 10-4 10/11 V19 N4 4/3/2012 0:00 10-4 Magazine *AL* 04/12 V19 N10 11/14/2014 0:00 100 Bullets 03/08 N87 11/14/2014 0:00 100 Bullets 11/07 N85 !1 11/14/2014 0:00 100 Bullets 05/05 N59 11/14/2014 0:00 100 -

Pow Wow Dances

Pow Wow Dances Activity Information Grade Appropriate Level: Grade K - 3 Duration : Three, 30 minute classes. Materials: Classroom or library access to internet. Paper for drawing, markers, pencil colours, crayons, large area for movement. Objective • Children will gain a greater appreciation for other cultures and their ceremonies and traditions by learning about Pow Wow style dances and their connections to the environment. Prescribed Learning Outcomes It is expected that students will: • move expressively to a variety of sounds and music. • create movements that represent patterns, characters, and other aspects of their world. • organize information into sequenced presentations that include a beginning, middle, and end. • demonstrate awareness of British Columbia's and Canada's diverse heritage. Skills Researching, analyzing results, singing, dancing, presenting material Introductory Activity • The teacher reads a brief description of the history and purpose of the Pow Wow to the class from the “About Pow Wows” sheet (included in package) • Have students listen to dance music and songs. Children can view and discover different Pow Wow dance styles, music and dress from the following website: http://www.ktca.org/powwow/dances.html Some information from the website has been included as .pdf files at the end of this lesson plan in the event the website is down or can’t be accessed. Suggested Instructional Strategies 1. List the different competition categories for Pow Wow dancers on the board. ie. Fancy dancers. (Found in “About Pow Wow” from INAC sheet included in resource package.) 2. Dancers wear regalia with fringes of yarn or fabric on their aprons, capes, and leggings. -

Magazines V17N9.Qxd

May COF C1:COF C1.qxd 4/16/2009 1:23 PM Page 1 David Petersen's Acclaimed Mouse Guard Returns In Archaia's New Hardcover Collection May 2009 DUE DATE: MAY 16, 2009 Name Project2:Layout 1 4/16/2009 9:20 AM Page 1 COF Gem Page May:gem page v18n1.qxd 4/16/2009 3:26 PM Page 1 BLACKEST NIGHT #1 DC COMICS STAR WARS: INVASION #1 DARK HORSE COMICS CREEPY #1 DARK HORSE COMICS GREEK STREET #1 DC COMICS/VERTIGO CRIME THE MICE TEMPLAR: DESTINY #1 IMAGE COMICS MAGAZINE GEM OF THE MONTH HULK #600 MARVEL COMICS CYBERFORCE/ HUNTER-KILLER #1 WIZARD IMAGE COMICS/TOP COW STUDIOS MAGAZINE #214 COF FI Page May:COF FI Page December.qxd 4/16/2009 10:38 AM Page 1 featuredfeatured itemsitems PREMIER (GEMS) TOYS & MODELS Star Wars: Invasion #1 G Dark Horse Comics The Exorcist: Possessed Regan Electronic Creepy Comics #1 G Dark Horse Comics Deluxe Box Set G Horror Blackest Night #1 G DC Comics Little Big Planet 4-Inch Figures Series 1 G Video Games Greek Street #1 G DC Comics/Vertigo Walt Disney Classics Collection: Mice Templar: Destiny #1 G Image Comics Runaway Brain Figurines G Disney Cyberforce/Hunter-Killer #1 G Star Wars: Boba Fett with Han in Carbonite Statue G Star Wars Image Comics/Top Cow Productions Incredible Hulk #600 G Marvel Comics Wizard Magazine #214 G Wizard Entertainment DESIGNER TOYS COMICS Barack Obama 6-Inch D.I.Y. Version Action Figure G Designer Toys Mouse Guard Volume 2: Winter 1152 HC G Mickey Mouse: Runaway Brain Archaia Studios Press “Candy Flake Version” Vinyl Figure G Designer Toys Political Power #1: Colin Powell G Bluewater Productions -

Liste Des Titres Famille / Série / Titre 1244 Enregistrements

Liste des titres Famille / Série / Titre 1244 enregistrements Titre Édition EO Etat Cote Prix 1244 COMICS 15 2099 COMICS n° 11238 2099 - N° 11 01/06/1994 Non Bon 0,00 € 8,00 € Couverture Cartonnée SEMIC Descriptif Défauts plats un peu frottés n° 11231 2099 - N° 14 01/09/1994 Non Bon 0,00 € 6,00 € Couverture Cartonnée SEMIC Descriptif Défauts n° 11230 2099 - N° 15 01/10/1994 Non Bon 0,00 € 6,00 € Couverture Cartonnée SEMIC Descriptif Défauts n° 11237 2099 - N° 18 01/01/1995 Non Très bon 0,00 € 8,00 € Couverture Cartonnée SEMIC Descriptif Défauts n° 11236 2099 - N° 20 01/03/1995 Non Bon 0,00 € 6,00 € Couverture Cartonnée SEMIC Descriptif Défauts n° 11235 2099 - N° 6 01/01/1994 Non Bon 0,00 € 6,00 € Couverture Cartonnée SEMIC Descriptif Défauts plats un peu frottés n° 11234 2099 - N° 7 01/02/1994 Non Bon 0,00 € 6,00 € Couverture Cartonnée SEMIC Descriptif Défauts plats un peu frottés jeudi 23 septembre 2021 Page 1 sur 180 Titre Édition EO Etat Cote Prix n° 11233 2099 - N° 8 01/03/1994 Non Bon 0,00 € 6,00 € Couverture Cartonnée SEMIC Descriptif Défauts plats un peu frottés n° 11232 2099 - N° 9 01/04/1994 Non Bon 0,00 € 6,00 € Couverture Cartonnée SEMIC Descriptif Défauts plats un peu frottés n° 11229 2099 - N°16 01/11/1994 Non Bon 0,00 € 6,00 € Couverture Cartonnée SEMIC Descriptif Défauts n° 16387 2099 - N°2 01/09/1993 Non Bon 10,00 € 7,00 € Couverture Brochée SEMIC Descriptif Défauts léger manque sur bas couverture arrière n° 16388 2099 - N°3 01/10/1993 Oui Bon 10,00 € 7,00 € Couverture Brochée SEMIC Descriptif Défauts n° 11228 2099 - N°5