Emerging Roles of Technology in Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Searchable PDF Index

TELEPHONE COLLECTORS INTERNATIONAL Telephone Collectors International is an organization of telephone collectors, hobbyists and historians who are helping to preserve the history of the telecommunications industry through the collection of telephones and telephone related material. Our collections represent all aspects of the industry; from the very first wooden prototypes that started the industry to the technological marvels that made the automatic telephone exchange possible. If any of this interests you, we invite you to join our organization. Look around and see what we have to offer. Thanks for stopping by! Telephone Collectors International website including become a member: http://www.telephonecollectors.org/ Questions or comments about TCI? Send e-mail to [email protected] ********************************************************************************* Books Recommended by the editors: Available now ... Old-Time Telephones! Design, History, and Restoration by Ralph O. Meyer ... 264pp Soft Cover 2nd Edition, Expanded and Revised ... A Schiffer Book with Price Guide for Collectors Available at Phoneco.com or Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., 4880 Lower Valley Rd, Atglen, PA 19310 e-mail: [email protected] ********************************************************************************** Coming Soon: TELEPHONE Dials and Pushbuttons Their History, Development and Usage by Stanley Swihart ... 2 volumes, 300 pp ea. Box 2818, Dublin, CA., 94568-0818. Phone 1 (925)-829-2728, e-mail [email protected] ********************************************************************************* -

Telephone Sets-Modular Type

BELL SYSTEM PRACTICES SECTION 503-100-1 00 AT& TCo Standard Issue 5, April 1979 TELEPHONE SETS-MODULAR TYPE 1. GENERAL • Show current production 630A4 connecting block 1.01 This section contains general information on the modular concept of telephone sets. • Revise Tables A, C, F, G and Fig. 4, 5. 1.02 This section is reissued to: Since this reissue covers a general revision, arrows ordinarily used to indicate changes have been • Add 158A cover omitted. • Add 625FS and G25H connecting blocks 1.03 The modular telephone set is the same as the standard telephone set except the • Add 616W3 and 623D6 jacks telephone set base and handset are jack equipped to accept a plug-ended mounting cord (desk set) • Add lA converter and handset cord (wall and desk sets). Modular wall sets are equipped with a plug to mount on a • Add information on the 228-, 229-, and 630A4 connecting block. 230-type adapters 1.04 Modular telephone sets are available assembled • Add caution information on the 267A adapter (less cords) or as components (housing, handset, telephone set base, etc.). See Tables A • Add 227C, 227D, 248B, 281A, 282A, and through D. 304A adapters 1.05 This section provides for the installation of • Add information on routing of 523A-type connecting blocks, modular telephone sets, plug leads used to convert nonmodular wall and modular components; conversion and/or repair telephone sets to modular of nonmodular telephone sets and nonmodular components. • Add information on 635B connecting block • Add information on D impact tool and 8762D-630 blade 2. IDENTIFICATION • Add D8AA mounting cord 2.01 When installing modular telephone sets or converting sets to modular, various items • Add 523A4B wall set plug of the following auxiliary apparatus will be required. -

220-, 226-, 2220-, and 2226-Type Hand Telephone Sets

BELL SYSTEM PRACTICES SECTION 502-303-1 02 AT&TCo Standard Issue 3, October 1981 220-, 226-, 2220-, AND 2226-TYPE HAND TELEPHONE SETS IDENTIFICATION, INSTALLATION, CONNECTIONS, AND MAINTENANCE 1. GENERAL 1.01 This section contains information for the 220-, 226-, 2220-, and 2226-type hand telephone sets (Fig. 1, 2, and 3). 1.02 The reasons for reissuing this section are listed below. Revision arrows are used to em phasize the more significant changes. • Add the 315B amplifier for 226A hand tele phone set • Show the 315A amplifier (MD) for 226A hand telephone sets • Change Fig. 25 and 26. 2. IDENTIFICATION 2.01 The 220A (MD), 220C, 220AL, 220AM, and 226A rotary dial and 2220B (MD), 2220C, FLOATING 2220BM, and 2226A TOUCH-TONE* dialing hand FINGER STOP telephone sets are intended for use with other compo nents and apparatus to make up a complete telephone set. Refer to Table A for identification of associated apparatus. 2.02 These handsets are presently used with the TRIMLINE* telephone, Transaction, Eleva tor, Conference, and some DESIGN LINEt decorator telephones. 2.03 They consist primarily of a plastic deck and shell, a dial, flexible circuit board (network), handset cord jack, transmitter, and receiver units. Fig. 1-220-Type Hand Telephone Set 2.04 The 220A (MD) and 2220B handsets are equipped with jacks which accept the large *Registered Trademark of American Telephone and Telegraph Company. fl'rademark of American Telephone and Telegraph Company. NOTICE Not for use or disclosure outside the Bell System except under written agreement Printed in U.S.A. Page 1 SECTION 502-303-1 02 315-TYPE AMPLIFIER COVER VOLUME CONTROL 83A2B DIAL RECALL SWITCH NOTE: 22209 AND 222081! 226A HANDSET HANDSETS HAVE SA ME , EXCEPT ROUND DIAL HAS ROTARY DIAL. -

Telephone Services for the Handicapped. Rehabilitation Monograph XXXVII. INSTITUTION New York Univ., N.Y

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 037 856 EC 005 247 kUmHOR Sullivan, Richard A.; And Others TImLE Telephone Services for the Handicapped. Rehabilitation Monograph XXXVII. INSTITUTION New York Univ., N.Y. Medical Center. SPONS AGENCY American Telephone and Telegraph, New York, N.Y. PU_,? DATE 68 NOT 152p. FDPS PRICE EDPS Price MP' -$0n 75 HC-$7070 DESCRIPTORS Audio Equipment, Equipment Evaluation, Equipment Utilization, *Exceptional Child Services, *Physically Handicapped, Sensory Aids, *Telephone Communication Systems AESTPACT A study by American Telephone and Telegraph investigated the use of standard Bell equipment in meeting the needs of the disabled for telephone service. Results revealed that all disabled persons who are able to communicate orally can initiate and terminate a call and carry on a conversation when the correct types of equipment are found, especially when push button dials are universally available or when an operator is available. The monograph presents information on the difficulties encountered in using the phone and on equipment found useful. Each phone, headset, or modification is described through words and by photographs; advantages and disadvantages are noted. Several factors influencing the choice of telephone equipment (answering in time, access, and family use) are considered. Evaluation of the patient and the equipment is discussed in regard to the amount of physical function present and the testing and matching of equipment for various disabilities. Choice of telephone, assistive devices, special services for summoning aid, use of the phone for home business, and coin phones for wheelchair users are also mentioned. (RJ) 4 sr-2S OA S. gio I 1 co° 4 ' U I I alb 0 0.4.4. -

Fuelling the Future with Hydrogen

VOLUME 4 ISSUE 3 SPRING 2002 UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO APPLIED SCIENCE & ENGINEERING PLUS ENGINEERING BUSINESS SUCCESS: HANA ZALZAL FORMULA SAE: FROM THE CLASSROOM TO THE RACETRACK IN 2.9 SECONDS FUELLING THE FUTURE WITH E R I V S I T HYDROGEN N Y U Skule alumni are confident that hydrogen will be the key to O O F T sustainable energy in the future T O R O N insideskule FEATURES 12 Fuelling the Future with Hydrogen 16 Engineering Business Success: Hana Zalzal 18 Formula SAE: From the Classroom to the Racetrack in 2.9 Seconds 20 Great Teachers 22 UofT Engineers take on International Development 16 18 9 COLUMNS & NEWS 3 From the Dean 4 Research and Graduate Studies 5 For High School Students From the Alumni Office 6 From the Development Office 22 Planned Giving 7 Professional Development 8 8 Skulenews Volume 4, Issue 3, Contributing Editors: Illustration: Sanford Kong copyrighted. Limited portions concerning active participation Spring 2002 Will Cluett, Márta Ecsedi, Printing: General Printers. of its content may be reprinted in Faculty programs, and Cindy Yelle Published in Fall, Winter or reproduced without the comments and suggestions A magazine for alumni, Design: Shelley Frayer/ and Spring as a service to prior written consent of the from readers. students, and friends of the Ireland+Associates alumni, students, and copyright owner only if Please contact: Faculty of Applied Science Principal Photographers: friends of the Faculty of appropriately attributed. Professor Anastasios and Engineering Stephen Frost, Lisa Sakulensky Applied Science and Otherwise, its reproduction Venetsanopoulos, Dean, Editor: Contributing Photographers: Engineering, University of in whole or in substantial Faculty of Applied Science Anastasios N. -

Singing Wireswiresnewsletter

Telephone Collectors International SingingSinging WiresWiresNewsletter Volume 18, Number 10 October 15, 2004 Inside this issue . A Conversation with Donald Genaro 40 Years Ago... 1964/1965 New York – a Living Legend of Telephone Design World's Fair - Jonathan D. Finder, MD World's Fair Booths Feature Push-Button Calling When one thinks of telephone work of designers who were hired after the Pg 6 designers, one name tends to come up, that fact to “soften” products after they had been of Henry Dreyfuss (1904-1972). The created. Dreyfuss’ firm used measurements North of the Border designers of the early telephones were from thousands of people to establish Awards & Show probably anonymous employees of the Bell normal values on which to base the human Photos System (as well as of the independent elements of design (like the distance Pg 11 telephone manufacturers) who were between mouth and ear in the rational design engineers first and designers second. Bell of the telephone handset). These many Laboratories realized that their telephones measurements (the science of which is were lacking in design and so in 1929 held a known as anthropometrics) resulted in the “Telephone of the Future” contest. This publication of the industry standard contest was won by a 25 year old man named guidebook, The Measure of Man: Human Ring, Talk and Listen... Pg 7 Henry Dreyfuss. Factors in Design by Henry Dreyfuss Decisive Moments in His first telephone for the Bell Associates in 1960. This book remains in Telecommunications History: System, the WE302 (or “H” mounting), still print, revised and updated, most recently in The Bell System's First New stands as a hallmark in American design and 2001, and renamed The Measure of Man and Automatic Dial System is still being produced today (after a fashion, Woman: Human Factors in Design. -

Alphabetic-Numeric Index Station, KEY, PBX, and Private-Service

BELL SYSTEM PRACTICES SECTION 460-000-006 AT&TCo Standard Issue 6, February 1979 ALPHABETIC-NUMERIC INDEX A STATION, KEY, PBX, AND PRIVATE - SERVICE SYSTEMS FutEm m 1. GENERAL Here is a list of the symbols and the service manual to which they refer. 1.01 This section provides an alpha-numeric index of sections required for the installation and maintenance of customer product equipment and SA–Station Service Manual I apparatus. SB–Station Service Manual II SC–Station Specialties Service Manual I 1.02 This section is reissued to update the SD–Station Specialties Service Manual H alpha-numeric index. CA–Coin Service Manual I CB–Coin Service Manual II 1.03 This index combines the features of both IA–Interconnect Service Manual I alphabetic and numeric indexes. Sections IB–Interconnect Service Manual II can be located by referring first to the common KA–Key Service Manual I nomenclature or ordering nomenclature, then referring KB–Key Service Manual H to a major indention for the type of information KC–Key Service Manual III such as Identification, Installation, Maintenance, PA–Dial PBX Service Manual Reference, Service, etc., and then to the alphabetical or numerical listing. 1.04 Many of the section numbers in this index are preceded by a two letter symbol such as SA. This symbol indicates that the section is contained in a service manual in addition to the standard BSP files. NOTICE Not for use or disclosure outside the Bell System except under written agreement Printed in U.S.A. Page 1 SECTION 460-000-006 AC-TYPE (USED WITH 220-, 22&, 2220-, -

220-, 226-, 2220-, and 2226-Type Hand Telephone Sets

BELL SYSTEM PRACTICES SECTION 502-303-1 02 AT & TCo Standard Issue 2, December 1979 220-, 226-, 2220-, AND 2226-TYPE HAND TELEPHONE SETS IDENTIFICATION, INSTALLATION, CONNECTIONS, AND MAINTENANCE 1. GENERAL 1.01 This section contains information for the 220-, 226-, 2220-, and 2226-type hand telephone sets (Fig. 1, 2, and 3). • 1.02 This section is reissued to: • Add Brown (-104) and Rust (-124) colors, Table B COVER • Add information on D-180891 Kit of Parts (Radio Frequency Interference) • Remove information on 220B (MD) hand telephone set. 2. IDENTIFICATION DIAL 2.01 The 220A (MD), 220C, 220AL, 220AM, and 226A rotary dial and 2220B (MD), 2220C, 2220BM, and 2226A TOUCH-TONE"' dial hand telephone sets are intended for use with other components and apparatus to make up a complete telephone set. Refer to Table A for identification of associated apparatus. RECALL � BUTTON 2.02 These handsets are presently used with the ...... TRIMLINE"' telephone, Transaction, Elevator, ..... Conference, and some DESIGN LINE* telephone .... .. .. sets. ..... .. 2.03 They consist primarily of a plastic deck and shell, a dial, flexible circuit board (network), handset cord jack, transmitter, and receiver units. 2.04 The 220A and 2220B handsets are equipped with jacks which accept the large (maxi) Fig. 1- 220-Type Hand Telephone Set plugs for the H4DB, H5AA, or H5AD handset cord. The 220C, 220AL, 220AM, 226A, 2220C, 2220BM, *Trademark of AT&TCo. NOTICE Not for use or disclosure outside the Bell System except under written agreement Printed in U.S.A. Page 1 SSP S02-303·102-i02_1979·12-0l.jpg Scanned by Frank Harrell, (Cowboy Frank) Castle Rock, Colorado Feb 07, 2012 13:25:20 SECTION 502-303-1 02 315-TYPE AMPLIFIER VOLUME CONTROL RECALL SWITCH NOTE· 22208 AND 2220BM NOTE HANDSETS HAVE 226A HAND SET ROUND DIAL SAME, EXCEPT BUTTONS HAS ROTARY DIAL. -

Public Notice Federal Communications Commission 445 12Th Street, S.W

PUBLIC NOTICE FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION 445 12TH STREET, S.W. WASHINGTON, D.C. 20554 ___________________________________________________________ News Media Information (202) 418-0500 Report N-204-A Internet http://www.fcc.gov Released: January 12, 2001 CONNECTION OF TERMINAL EQUIPMENT TO THE TELEPHONE NETWORK The Common Carrier Network Services Registrations listed in this report were granted by authorized TELECOMMUNICATION CERTIFICATION BODIES (TCB’s) *********************************************************************************** EQUIPMENT REGISTRATION BY TELECOMMUNICATION CERTIFICATION BODIES (TCB’s) Eleven TCB’s have been authorized to issue Part 68 compliance certificates. A list of ANSI accredited TCB’s is accessible at the Part 68 Homepage (http://www.fcc.gov/ccb/nsd/documents/PART68.HTML) or go directly to the ANSI website (http://web.ansi.org/public/ca/ansi_cp.html). *********************************************************************************** INTERNET ACCESS TO REFERENCE AND CONTACT INFORMATION FCC NETWORK SERVICES DIVISION (NSD) HOME PAGE FOR PART 68 http://www.fcc.gov/ccb/nsd/documents/PART68.HTML - Send comments regarding site access and the information contained to [email protected] * * HYPERTEXT LINK TO NEW WEB SITE LISTINGS * * REPORTS OF APPLICATIONS RECEIVED AND APPLICATIONS GRANTED - Provides access to recent reports http://www.fcc.gov/ccb/nsd/documents/PART68PN.HTML REFERENCES AND CONTACT INFORMATION FOR PART 68 EQUIPMENT REGISTRATION - Provides hypertext links to FCC Rules, Industry Guide, and Part -

Station Transformers Identification

BELL SYSTEM PRACTICES SECTION 50 1-136- 100 AT & TCo Standard Issue 7, November 1979 STATION TRANSFORMERS IDENTIFICATION GENERAL unit to be in close proximity to the ac line source is not recommended. 1.01 This section contains information on station transformers. 1.03 Locate transformers where they will be accessible for inspection and maintenance. 1.02 This section is reissued to: 1.04 Transformers discussed in this section require • Show KS-20426L3 transformer MD a 110- to 125-volt ac power service outlet. • Revise Table A. Make sure that power service outlet is not under control of a switch. Danger: When providing power for illuminated station sets, two or more transformers should never feed the same inside wiring pair. If one 1.05 To prevent accidental removal, power cords transformer is unplugged while the may be fastened to the ac outlet with a secondary terminals of that transformer power-cord plug-retainer assembly (Section 167-400-210) are being energized through the inside and plug-in transformers may be secured with a wiring, by another transformer, the clamp. A clamp is furnished with some of the exposed terminal blades of the KS-20426L3 (MD) transformers, others have a unplugged transformer would be molded mounting tab. A retaining clamp is available energized with 110 to 125 volts ac. for the 85B1 and 95B1 power units. The 2012-type Installations of multiple transformers transformer may be secured with a 2A clamp. connected to the same inside wiring pair should be avoided and corrected if encountered in the field. 1.06 The B cord clip (size 1) provides a means of attaching D station wire to station transformers to prevent the wire being accidentally Warning: Care should be taken to pulled from the transformer screw terminals. -

Bell Laboratories Record Vol 54 Bell's Great Invention: Life Begins at 50

Bell Laboratories Record Vol 54 Bell's great invention: life begins at 50 I T WAS the jazz-bewitched 1920s. Depression clouds still hung over That decision paid off. The 500- Movies became talkies in 1926 1937 when the third generation of type set appeared in 1949. With with the first full-length motion pic- desk phones-the 300-type tele- years of research and development, ture using equipment developed by phone set-was born. A much im- plus human-factors engineering be- Bell Labs. The same year the tele- proved design, the set's bell and as- hind it, the fourth-generation 500 phone, a necessity now in millions sociated equipment were in the base set added even more naturalness of homes and businesses, celebrated instead of in a separate wall box. and intelligibility to speech. Styling its 50th birthday. The 300 set was the first phone to was modern, and the adjustable The pedestal-or candlestick- have an anti-sidetone network that ringer was more effective. The user desk set was the instrument of the minimized the sound of your own could set it to ring loud or soft, and era, although many of the earlier voice in the receiver as you spoke. it was lower pitched. The improved wall phones were still in service. N a- A new transmitter and a new re- transmission and ringer allowed the tionwide calling using long-distance ceiver helped improve fidelity, and 500 set to operate on circuits with operators was commonplace. Some the set was less susceptible to line higher resistance. -

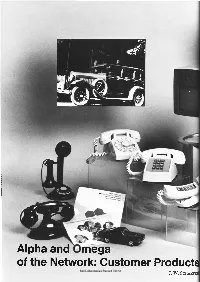

Bell Laboratories Record Vol 53 Bell Laboratories Record Vol 53 HAT IS the "BELL SYSTEM" to Our Cus- Timism and Progress

Bell Laboratories Record Vol 53 Bell Laboratories Record Vol 53 HAT IS THE "BELL SYSTEM" to our cus- timism and progress. Despite a semi-official Wtomers? It's the equipment-and the ser- government policy of political isolationism, vice that is its natural accompaniment-which foreign trade and travel increased. Automo- they see and use in their own homes, factories, biles and electric power were changing our and offices. This terminal equipment, called way of life. Americans in both business and customer products in telephone language, has private life were stepping into a broader, characteristics quite different from much of faster-moving world, and it was inevitable the rest of the telephone "plant." It's on the that they would need-and demand-more customer's premises and hence it's highly vis- and better communication facilities. It was ible, so it must have a pleasing appearance. the role of Bell Labs engineers to aid the Bell Each customer pays for the full use of this System to be one step ahead of these demands, kind of equipment, and since its use is shared by continually improving the telephone system with no one else, it is extremely cost-sensitive. they inherited from their predecessors at Customer products are the telephone system's AT&T and Western Electric. interface with its human users; consequently, In their efforts to anticipate and satisfy the design of the equipment heavily involves these demands, Bell Labs often saw solutions human factors and is directly subject to to problems outside the accepted definition of changes in perceived needs.