Korean Cabinet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Three Revolutions of Syngman Rhee

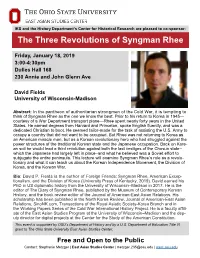

IKS and the History Department’s Center for Historical Research are pleased to co-sponsor: The Three Revolutions of Syngman Rhee Friday, January 18, 2019 3:00-4:30pm Dulles Hall 168 230 Annie and John Glenn Ave David Fields University of Wisconsin-Madison Abstract: In the pantheon of authoritarian strongmen of the Cold War, it is tempting to think of Syngman Rhee as the one we know the best. Prior to his return to Korea in 1945— courtesy of a War Department transport plane—Rhee spent nearly forty years in the United States. He earned degrees from Harvard and Princeton, spoke English fluently, and was a dedicated Christian to boot. He seemed tailor-made for the task of assisting the U.S. Army to occupy a country that did not want to be occupied. But Rhee was not returning to Korea as an American miracle man, but as a Korean revolutionary hero who had struggled against the power structures of the traditional Korean state and the Japanese occupation. Back on Kore- an soil he would lead a third revolution against both the last vestiges of the Chosun state– which the Japanese had largely left in place–and what he believed was a Soviet effort to subjugate the entire peninsula. This lecture will examine Syngman Rhee’s role as a revolu- tionary and what it can teach us about the Korean Independence Movement, the Division of Korea, and the Korean War. Bio: David P. Fields is the author of Foreign Friends: Syngman Rhee, American Excep- tionalism, and the Division of Korea (University Press of Kentucky, 2019). -

A Legal Study of the Korean War Howard S

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Review Akron Law Journals July 2015 How It All Started - And How It Ended: A Legal Study of the Korean War Howard S. Levie Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Levie, Howard S. (2002) "How It All Started - And How It Ended: A Legal Study of the Korean War," Akron Law Review: Vol. 35 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol35/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Levie: A Legal Study of the Korean War LEVIE1.DOC 3/26/02 12:29 PM HOW IT ALL STARTED - AND HOW IT ENDED: A LEGAL STUDY OF THE KOREAN WAR Howard S. Levie A. World War II Before taking up the basic subject of the discussion which follows, it would appear appropriate to ascertain just what events led to the creation of two such disparate independent nations as the Republic of Korea (hereinafter referred to as South Korea) and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (hereinafter referred to as North Korea) out of what had been a united territory for centuries, whether independent or as the possession of a more powerful neighbor, Japan — and the background of how the hostilities were initiated in Korea in June 1950. -

The Partition of Korea After World War II This Page Intentionally Left Blank the PARTITION of KOREA AFTER WORLD WAR II

The Partition of Korea after World War II This page intentionally left blank THE PARTITION OF KOREA AFTER WORLD WAR II A GLOBAL HISTORY Jongsoo Lee THE PARTITION OFKOREA AFTER WORLD WAR II © Jongsoo Lee, 2006. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2006 978-1-4039-6982-8 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. First published in 2006 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN™ 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 and Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, England RG21 6XS Companies and representatives throughout the world. PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-1-349-53150-9 ISBN 978-1-4039-8301-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9781403983015 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lee, Jongsoo. The partition of Korea after world war II : a global history / Jongsoo Lee. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Korea—History—Partition, 1945– 2. World War, 1939–1945— Diplomatic history—Soviet Union. 3. World War, 1939–1945— Diplomatic history—United States. 4. Korea—History—Allied occupation, 1945–1948. I. Title. DS917.43.L44 2006 951.904Ј1—dc22 2005054895 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Design by Newgen Imaging Systems (P) Ltd., Chennai, India. -

Surviving Through the Post-Cold War Era: the Evolution of Foreign Policy in North Korea

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal Title Surviving Through The Post-Cold War Era: The Evolution of Foreign Policy In North Korea Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4nj1x91n Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal, 21(2) ISSN 1099-5331 Author Yee, Samuel Publication Date 2008 DOI 10.5070/B3212007665 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Introduction “When the establishment of ‘diplomatic relations’ with south Korea by the Soviet Union is viewed from another angle, no matter what their subjective intentions may be, it, in the final analysis, cannot be construed otherwise than openly joining the United States in its basic strategy aimed at freezing the division of Korea into ‘two Koreas,’ isolating us internationally and guiding us to ‘opening’ and thus overthrowing the socialist system in our country [….] However, our people will march forward, full of confidence in victory, without vacillation in any wind, under the unfurled banner of the Juche1 idea and defend their socialist position as an impregnable fortress.” 2 The Rodong Sinmun article quoted above was published in October 5, 1990, and was written as a response to the establishment of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union, a critical ally for the North Korean regime, and South Korea, its archrival. The North Korean government’s main reactions to the changes taking place in the international environment during this time are illustrated clearly in this passage: fear of increased isolation, apprehension of external threats, and resistance to reform. The transformation of the international situation between the years of 1989 and 1992 presented a daunting challenge for the already struggling North Korean government. -

Korean War Module Day 01

KOREAN WAR MODULE DAY 01 MODULE OVERVIEW HISTORICAL THINKING SKILLS: CONTENT: Developments and Processes People and states around the world 1.B Explain a historical concept, development, or challenged the existing political and social process. order in varying ways, leading to Claims and Evidence in Sources unprecedented worldwide conflicts. 3.B Identify the evidence used in a source to support an argument. 3.C Compare the arguments or main ideas of two sources. 3.D Explain how claims or evidence support, modify, or refute a source’s argument Argumentation 6.D Corroborate, qualify, or modify an argument using diverse and alternative evidence in order to develop a complex argument. This argument might: o Explain the nuance of an issue by analyzing multiple variables. o Explain relevant and insightful connections within and across periods. D WAS THE KOREAN WAR A PRODUCT OF DECOLONIZATION OR THE COLD WAR? A Y CLASS ACTIVITY: Structured Academic Controversy 1 Students will engage in a Structured Academic Controversy (SAC) to develop historical thinking skills in argumentation by making historically defensible claims supported by specific and relevant evidence. AP ALIGNED ASSESSMENT: Thesis Statement Students will analyze primary and secondary sources to construct arguments with multiple claims and will focus on creating a complex thesis statement that evaluates the extent to which the Korean War was a product of decolonization and the Cold War. D EVALUATE THE EXTENT TO WHICH HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENTS IN THE POST- A WAR PERIOD WERE CAUSED BY DECOLONIZATION OR THE COLD WAR? Y CLASS ACTIVITY: Gallery Walk 2 Students will analyze multiple primary and secondary sources in a gallery walk activity. -

Abl25thesispdf.Pdf (2.788Mb)

THE HOPE AND CRISIS OF PRAGMATIC TRANSITION: POLITICS, LAW, ANTHROPOLOGY AND SOUTH KOREA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Amy Beth Levine May 2011 © 2011 Amy Beth Levine THE HOPE AND CRISIS OF PRAGMATIC TRANSITION: POLITICS, LAW, ANTHROPOLOGY AND SOUTH KOREA Amy Beth Levine, Ph.D. Cornell University 2011 This dissertation demonstrates how the urgent condition of crisis is routine for many non-governmental (NGO) and non-profit organization (NPO) workers, activists, lawyers, social movement analysts, social designers and ethnographers. The study makes a contribution to the increasing number of anthropological, legal, pedagogical, philosophical, political, and socio-legal studies concerned with pragmatism and hope by approaching crisis as ground, hope as figure, and pragmatism as transition or placeholder between them. In effect this work makes evident the agency of the past in the apprehension of the present, whose complexity is conceptualized as scale, in order to hopefully refigure ethnography’s future role as an anticipatory process rather than a pragmatic response to crisis or an always already emergent world. This dissertation is based on over two years of fieldwork inside NGOs, NPOs, and think tanks, hundreds of conversations, over a hundred interviews, and archival research in Seoul, South Korea. The transformation of the “386 generation” and Roh Moo Hyun’s presidency from 2003 to 2008 serve as both the contextual background and central figures of the study. This work replicates the historical, contemporary, and anticipated transitions of my informants by responding to the problem of agency inherent in crisis with a sense of scale and a rescaling of agency. -

Christian Communication and Its Impact on Korean Society : Past, Present and Future Soon Nim Lee University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year Christian communication and its impact on Korean society : past, present and future Soon Nim Lee University of Wollongong Lee, Soon Nim, Christian communication and its impact on Korean society : past, present and future, Doctor of Philosphy thesis, School of Journalism and Creative Writing - Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3051 This paper is posted at Research Online. Christian Communication and Its Impact on Korean Society: Past, Present and Future Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Wollongong Soon Nim Lee Faculty of Creative Arts School of Journalism & Creative writing October 2009 i CERTIFICATION I, Soon Nim, Lee, declare that this thesis, submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of Creative Arts and Writings (School of Journalism), University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Soon Nim, Lee 18 March 2009. i Table of Contents Certification i Table of Contents ii List of Tables vii Abstract viii Acknowledgements x Chapter 1: Introduction 1 Chapter 2: Christianity awakens the sleeping Hangeul 12 Introduction 12 2.1 What is the Hangeul? 12 2.2 Praise of Hangeul by Christian missionaries -

Experiencing South Korea FPRI/Korea Society 2015 Korean

Experiencing South Korea FPRI/Korea Society 2015 Korean Presidents: an Evaluation of Effective Leadership Author: Ellen Resnek: Downingtown East High School Lesson Overview: Through the use of various primary and secondary sources, students in this lesson will identify, understand and be able to explain the Korean President Power Ranking: Technically, the Republic of Korea has had ten heads of government since its birth in 1948: (1) Syngmn Rhee (1948-1960); (2) Chang Myon (1960-1961); (3) Park Chung-hee (1961-1979); (4) Choi Gyu-ha (1979-1980); (5) Chun Doo-hwan (1980-1987); (6) Roh Tae-woo (1987-1992); (7) Kim Young-sam (1992-1997); (8) Kim Dae-jung (1997-2002); (9) Roh Moo-hyun (2002-2007) ; (10) Lee Myeong-bak (2007-2012).; and Park Geun-hye, 2013–current. But one can see that Chang Myon and Choi Gyu-ha did not last very long, because they abdicated from their posts when their successors rolled into Seoul with tanks. Objectives: 1. Students will learn background information regarding Korean President Power 2. Students will develop an appreciation of people who have helped shape the history and culture of Korea. 3. Students will become aware of some of the most important events in Korean history. 4. Students will examine various leadership styles and determine those the students might want to emulate. Materials Required Handouts provided Computers for research While this lesson is complete in itself, it can be enriched by books on Korea and updated regularly by checking the Internet for current information. Experiencing South Korea FPRI/Korea Society 2015 Procedure: Lesson Objectives: Students will be able to: Evaluate authors’ differing points of view on the same historical event or issue by assessing the authors’ claims, reasoning, and evidence Determine an author’s point of view or purpose in analyzing how style and content contribute to the power, persuasiveness, or beauty of the text. -

![September 30, 1949 Letter, Syngman Rhee to Dr. Robert T. Oliver [Soviet Translation]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6467/september-30-1949-letter-syngman-rhee-to-dr-robert-t-oliver-soviet-translation-696467.webp)

September 30, 1949 Letter, Syngman Rhee to Dr. Robert T. Oliver [Soviet Translation]

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified September 30, 1949 Letter, Syngman Rhee to Dr. Robert T. Oliver [Soviet Translation] Citation: “Letter, Syngman Rhee to Dr. Robert T. Oliver [Soviet Translation],” September 30, 1949, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, CWIHP Archive. Translated by Gary Goldberg. https://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/119385 Summary: Letter from Syngman Rhee translated into Russian. The original was likely found when the Communists seized Seoul. Syngman Rhee urges Oliver to come to South Korea to help develop the nation independent of foreign invaders and restore order to his country. Credits: This document was made possible with support from the Leon Levy Foundation. Original Language: Russian Contents: English Translation Scan of Original Document continuation of CABLE Nº 600081/sh “30 September 1949 to: DR. ROBERT T. OLIVER from: PRESIDENT SYNGMAN RHEE I have received your letters and thank you for them. I do not intend to qualify Mr. KROCK [sic] as a lobbyist or anything of that sort. Please, in strict confidence get in contact with Mr. K. [SIC] and with Mr. MEADE [sic] and find out everything that is necessary. If you think it would be inadvisable to use Mr. K with respect to what Mr. K told you, we can leave this matter without consequences. In my last letter I asked you to inquire more about K. in the National Press Club. We simply cannot use someone who does not have a good business reputation. Please be very careful in this matter. There is some criticism about the work which we are doing. -

Foreign Aid and the Development of the Republic of Korea: the Effectiveness of Concessional Assistance

AID Evaluation Special Study No. 42 Foreign Aid and the Development of the Republic of Korea: The Effectiveness of Concessional Assistance December 1985 Agency for International Development (AID) Washington, D.C. 20523 PN-AAL-075 FOREIGN AID AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA: THE EFFECTIVENESS OF CONCESSIONAL ASSISTANCE AID SPECIAL STUDY NO. 42 by David I. Steinberg u.s. Agency for International Development October 1985 The views in this report are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Agency for International Development. TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface . ................................................... v Summary . ................................................... vii Glossary . .................................................. x Map . ...•.........•..••........••..•••••.•..•••...•.......•. xi 1 • In trod u c t ion . .• . • • • . • • . • • . • . • . 1 1.1 Background . ...................................... 1 1.2 On Folklore and Definitions ..•...•.•.........•.••• 3 1. 2 .1 Growth . .................................... 7 1. 2. 2 Equity . .................................... 7 1.3 Factors in Korean Growth and Equity •.••.•......... 9 1. 3.1 Ethnici ty an~ Culture .•.•.................. 9 1. 3. 2 Land Reform ................................ 11 1.3.3 Education ..•...........•.......•........... l3 1. 3. 4 The Mer i tocratic State ......•....•......... 16 2. Korean Growth ..•••..................................... 1 7 2.1 Economic Accomplishments of the Republic of Korea, 1953-1983 ....•......................••.. -

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT in the REPUBLIC of KOREA a Policy Perspective

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA A Policy Perspective Edited by Lee-Jay Cho and Yoon Hyung Kim ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA 126°E 130 ° E DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE'S ( REPUBLIC OF KOREA / (North Korea) .,/------ .. - .. - .--.-/ I ' .... rrl f" .,)~ ....... ~ 38°N .... : ' , ,/ KANGWON East Sea ,, -, , (Sea of Japan) ,( , KVONGGI j ,_~~-~ '" ,_..... ( /-/NORTH / "-~/ CH'UNGCH'ONG / " .-J-,_J _, r NORTH KVONGSANG -.... -- 36°N r ....... -\ Yellow Sea / .T~egu NORTH \ 'J ...... I CHOLLA , ,r- ' - ..... _"' .... ,--/ ... -- SOUTH KVONGSANG o {l.SUSHIMA 00 0 c[4o 0 0 :WON D' IS' :w ON 0 ---""'; f USS P Cheju SI,.it ;' po.t:' "5" :;:;!)A. I ~ SOlfJ1;l-KOREA (ROK) 5fI miles Pacific lr r Ocean 50 100 150 200 kilometers 126"E ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN THE REPUBLIC OF KOREA A Policy Perspective Edited by Lee-Jay Cho and Yoon Hyung Kim An East-West Center Book Distributed by the University of Hawaii Press © 1991 by the East-West Center All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Economic development in the Republic of Korea I edited by Lee-Jay Cho and Yoon Hyung Kim. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-86638-131-7 : $49.50 1. Korea (South)-Economic policy-1960- 2. Korea (South)-Social policy. 3. Industry and state-Korea (South) I. Cho, Lee-Jay. II. Kim, Yoon Hyung. HC467.E266 1991 338.95195-dc20 90-20706 CIP Published in 1991 by the East-West Center 1777 East-West Road, Honolulu, Hawaii 96848 Distributed by the University of Hawaii Press 2840 I<olowalu Street, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Contents List of Figures ix List of Tables xi Contributors xix Acknowledgments xxiii Preface xxv PART I: POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC BACKGROUND 1. -

Killing Hope U.S

Killing Hope U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II – Part I William Blum Zed Books London Killing Hope was first published outside of North America by Zed Books Ltd, 7 Cynthia Street, London NI 9JF, UK in 2003. Second impression, 2004 Printed by Gopsons Papers Limited, Noida, India w w w.zedbooks .demon .co .uk Published in South Africa by Spearhead, a division of New Africa Books, PO Box 23408, Claremont 7735 This is a wholly revised, extended and updated edition of a book originally published under the title The CIA: A Forgotten History (Zed Books, 1986) Copyright © William Blum 2003 The right of William Blum to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Cover design by Andrew Corbett ISBN 1 84277 368 2 hb ISBN 1 84277 369 0 pb Spearhead ISBN 0 86486 560 0 pb 2 Contents PART I Introduction 6 1. China 1945 to 1960s: Was Mao Tse-tung just paranoid? 20 2. Italy 1947-1948: Free elections, Hollywood style 27 3. Greece 1947 to early 1950s: From cradle of democracy to client state 33 4. The Philippines 1940s and 1950s: America's oldest colony 38 5. Korea 1945-1953: Was it all that it appeared to be? 44 6. Albania 1949-1953: The proper English spy 54 7. Eastern Europe 1948-1956: Operation Splinter Factor 56 8. Germany 1950s: Everything from juvenile delinquency to terrorism 60 9. Iran 1953: Making it safe for the King of Kings 63 10.