UC Natural Reserve System Transect Publication 20:2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE ENVIRONMENTAL LEGACY of the UC NATURAL RESERVE SYSTEM This Page Intentionally Left Blank the Environmental Legacy of the Uc Natural Reserve System

THE ENVIRONMENTAL LEGACY OF THE UC NATURAL RESERVE SYSTEM This page intentionally left blank the environmental legacy of the uc natural reserve system edited by peggy l. fiedler, susan gee rumsey, and kathleen m. wong university of california press Berkeley Los Angeles London The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous contri- bution to this book provided by the University of California Natural Reserve System. University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2013 by The Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The environmental legacy of the UC natural reserve system / edited by Peggy L. Fiedler, Susan Gee Rumsey, and Kathleen M. Wong. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-520-27200-2 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Natural areas—California. 2. University of California Natural Reserve System—History. 3. University of California (System)—Faculty. 4. Environmental protection—California. 5. Ecology—Study and teaching— California. 6. Natural history—Study and teaching—California. I. Fiedler, Peggy Lee. II. Rumsey, Susan Gee. III. Wong, Kathleen M. (Kathleen Michelle) QH76.5.C2E59 2013 333.73'1609794—dc23 2012014651 Manufactured in China 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 2002) (Permanence of Paper). -

Indian Joe Springs Ecological Reserve Land Management Plan (LMP)

State of California California Natural Resources Agency DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE FINAL LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN for INDIAN JOE SPRINGS ECOLOGICAL RESERVE Inyo County, California April, 2018 Indian Joe Springs Ecological Reserve -1- April, 2018 Land Management Plan INDIAN JOE SPRINGS ECOLOGICAL RESERVE FINAL LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN Indian Joe Springs Ecological Reserve -ii- April, 2018 Land Management Plan This Page Intentionally Left Blank Indian Joe Springs Ecological Reserve -iv- April, 2018 Land Management Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. TABLE OF CONTENTS v LIST OF FIGURES vii LIST OF TABLES vii I. INTRODUCTION 1 A. Purpose of and History of Acquisition 1 B. Purpose of This Management Plan 1 II. PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 2 A. Geographical Setting 2 B. Property Boundaries and Adjacent Lands 2 C. Geology, Soils, Climate, Hydrology 3 D. Cultural Features 13 III. HABITAT AND SPECIES DESCRIPTION 15 A. Vegetation Communities, Habitats 15 B. Plant Species 18 C. Animal Species 20 D. Threatened, Rare or Endangered Species 22 IV. MANAGEMENT GOALS AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS 35 A. Definition of Terms Used in This Plan 35 B. Biological Elements: Goals & Environmental Impacts 35 C. Biological Monitoring Element: Goals & Environmental Impacts 39 D. Public Use Elements: Goals & Environmental Impacts 41 E. Facility Maintenance Elements: Goals & Environmental Impacts 44 F. Cultural Resource Elements: Goals & Environmental Impacts 46 G. Administrative Elements: Goals & Environmental Impacts 46 V. OPERATIONS AND MAINTENANCE SUMMARY 48 Existing Staff and Additional Personnel Needs Summary 48 VI. CLIMATE CHANGE STRATEGIES 48 VII. FUTURE REVISIONS TO LAND MANAGEMENT PLANS 51 VIII. REFERENCES 54 Indian Joe Springs Ecological Reserve -v- April, 2018 Land Management Plan APPENDICES: A. -

UC San Diego Capstone Papers

UC San Diego Capstone Papers Title Developing a Draft Management Plan for the Dike Rock Intertidal Area Scripps Coastal Reserve, La Jolla, California Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4c57b1bc Author Som, Marina Publication Date 2015-04-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California !"#"$%&'()*+*!,+-.*/+(+)"0"(.*1$+(*-%,*.2"*!'3"*4%53*6(.",.'7+$*8,"+* 95,'&&:*;%+:.+$*4":",#"* <+*=%$$+>*;+$'-%,('+* ! ! ! ! ! "#$%&#!'()! "#*+,$!(-!./0#&1,/!'+2/%,*! "#$%&,!3%(/%0,$%*+4!5!6(&*,$0#+%(&! '1$%77*!8&*+%+2+%(&!(-!91,#&(:$#7;4! <&%0,$*%+4!(-!6#=%-($&%#>!'#&!?%,:(! ! @2&,!ABCD! ! 6#7*+(&,!6())%++,,E! 8*#F,==,!G#4>!<&%0,$*%+4!(-!6#=%-($&%#!H#+2$#=!I,*,$0,!'4*+,)!J6;#%$K! @,&&%-,$!')%+;>!L;M?M>!'1$%77*!8&*+%+2+%(&!(-!91,#&(:$#7;4! ! !"#$%!&$' ! !"#$%&'())*$+,-*.-/$0#*#'1#$2%+03$(*$,4#$,5$67$'#*#'1#*$(4$."#$84(1#'*(.9$,5$+-/(5,'4(-$28+3$ :-.;'-/$0#*#'1#$%9*.#<$2:0%3$#*.-=/(*"#>$=9$."#$8+$?,-'>$,5$0#@#4.*$.,$*;)),'.$;4(1#'*(.9A/#1#/$ '#*#-'&"B$#>;&-.(,4B$-4>$);=/(&$*#'1(&#C$$D$.#4A9#-'$'#1(#E$2F-9$GHHI3$,5$."#$%+0$(>#4.(5(#>$."-.$ ."#$'#*#'1#$5-&#*$#J.#'4-/$."'#-.*$.,$(.*$/,4@A.#'<$1(-=(/(.9$5',<$"#-19$);=/(&$;*#B$)-'.(&;/-'/9$(4$ ."#$*",'#/(4#K<-'(4#$),'.(,4$,5$."#$%+0B$-4>$'#&,<<#4>#>$."-.$."#$8+$%-4$L(#@,$.-M#$-$ *.',4@#'$',/#$(4$)',.#&.(4@$."#$4-.;'-/$'#*,;'&#*$/,&-.#>$E(."(4$."#$%+0C$$!"(*$>'-5.$<-4-@#<#4.$ )/-4$"-*$=##4$>#1#/,)#>$5,'$."#$-))',J(<-.#/9$NA-&'#$-'#-$',&M9$(4.#'.(>-/$),'.(,4$,5$."#$%+0$ M4,E4$-*$L(M#$0,&MC$!"#$);'),*#$,5$."(*$>'-5.$<-4-@#<#4.$)/-4$(*$.,$)',1(>#$-$<#&"-4(*<$5,'$ ."#$(4.#@'-.(,4$,5$(45,'<-.(,4$-4>$-$*.';&.;'#$5,'$."#$)',.#&.(,4B$<-4-@#<#4.B$-4>$;*#$,5$."#$ -

University of California Real Property Report

University of California Real Property Report Street Address / Other User Type Recording Date State or Consideration/ ID # Surplus City County Country Common Name Acres Parcel Number(s) Recording Data Use Book Value 01-00007 2612 Haste St. UCB Pur 055-1874-023-01 12/20/1957 Stu Hsg $67,500 Berkeley Alameda CA Unit 2 Residence Halls 0.069 Bk 8551 Page 39 01-00008 2644 Haste St. UCB Pur 12/19/1957 Stu Hsg $24,000 Berkeley Alameda CA Unit 2 Residence Halls 0.097 Bk 8550 Page 232 01-00009 2647 Dwight Way UCB Pur 1/6/1958 Stu Hsg $62,500 Berkeley Alameda CA Unit 2 Residence Halls 0.155 Bk 8560 Page 573 01-00010 2635 Dwight Way UCB Pur 11/27/1957 Stu Hsg $190,000 Berkeley Alameda CA Unit 2 Residence Halls Bk 8532 Page 144 01-00011 2649-51-53 Dwight Way UCB Pur 057-2042-004 1/31/1958 Stu Hsg $26,500 Berkeley Alameda CA Unit 2 Residence Halls 0.155 Bk 8584 Page 477 01-00012 2649-51-53 Dwight Way UCB Pur 1/31/1958 Stu Hsg Berkeley Alameda CA Unit 2 Residence Halls 0.155 Bk 8584 Page 482 01-00013 2649-51-53 Dwight Way UCB 1/31/1958 Stu Hsg Berkeley Alameda CA Unit 2 Residence Halls 0.155 Bk 8584 Page 468 01-00014 2411 Atherton St. UCB 2/25/1958 Child Study Ctr $20,000 Berkeley Alameda CA Jones Child Study Center 0.154 Bk 8603 Page 294 01-00015 2411 Atherton St. UCB 2/25/1958 Child Study Ctr $20,000 Berkeley Alameda CA Jones Child Study Center 0.154 Bk 8603 Page 292 01-00016 2634 Channing Way UCB Pur 3/20/1958 Land Bnkg $30,000 Berkeley Alameda CA Underhill Area 0.139 Bk 8624 Page 557 01-00017 2416 College Ave. -

UC Natural Reserve System Transect Publication 18:1

University of California TransectS u m m e r 2 0 0 0 • Volume 18, No.1 A few words from the NRS systemwide office oday the NRS’s 33 reserve sites,* encompassing roughly T 130,000 acres, are protected and managed in support of teaching, research, and outreach activities. The only people who live there now are a handful of reserve personnel — mostly resident managers and stewards — who care for these wildlands, their resources and facilities, and who enable the teaching and research to continue across California. But this was not always the case. Long before even the concept of Cali- fornia, other people lived out their lives on these lands. Hundreds and thou- sands of years ago, other people were finding ways to feed, clothe, shelter, Photo by Susan Gee Rumsey and protect themselves, trying their The past is nonrenewable: Continued on page 32 Natural reserves protect rich cultural resources 4 Firsthand impressions of a Santa Cruz Island dig ’ve done research at the UC Natural Reserve System’s site on Santa Cruz Island for over 20 years, including archaeological field schools (10 summers) 7 Archaeology sheds light on and National Science Foundation-supported research (6 years) since 1985. I Big Creek mussel mystery I also did my Ph.D. on the island (1980-83) and recorded the major chert quar- 17 Of mammoths and men ries of El Montañon and the microblade production industries in the China Harbor area. 20 Picturing the past in the East Mojave Desert Santa Cruz Island is a remarkable place, and its pre-European cultural resources 25 And a useful glossary of are among the most important and exceptionally well-preserved in the United anthropology terms, too! States. -

University of California Mildred E. Mathias Graduate

University of California NATURAL'RESERVE'SYSTEM' Mildred E. Mathias Graduate Student Research Grants 2014-15 ' APPLICANT'' Second'applicant' First'applicant' INFORMATION' (Joint'application'only)' First'/'given'name' ' ' Middle'name'(if'used)' ' ' Last'/'family'name' ' ' eHmail'address' ' ' ' ' U.S.'Postal'Service'' ' ' mailing'address' ' ' Daytime'phone'number(s)' ' ' Campus' ' ' ' Department' ' ' ' ' Advisor(s)' ' ' ' Year'in'program' ' ' ' RESEARCH'PROJECT' Title' ' ' ' ' Time'schedule' ' ' ' ' ' Other'Funding' sources' ' ' ' Select'each'reserve'where'you'intend'to'conduct'your'research' ' ' Angelo Coast Range Reserve Fort Ord Natural Reserve San Joaquin Marsh Reserve ' Año Nuevo Island Reserve Hastings Natural History Reservation Santa Cruz Island Reserve ' Blue Oak Ranch Reserve James San Jacinto Mountains Reserve Scripps Coastal Reserve ' Bodega Marine Reserve Jenny Pygmy Forest Reserve Sedgwick Reserve ' Box Springs Reserve Jepson Prairie Reserve SNRS – Yosemite Field Station ' Boyd Deep Canyon DRC Kendall-Frost Mission Bay Marsh Res. Stebbins Cold Canyon Reserve ' Burns Piñon Ridge Reserve Landels-Hill Big Creek Reserve Steele/Burnand Anza-Borrego DRC ' Carpinteria Salt Marsh Reserve McLaughlin Natural Reserve Stunt Ranch Santa Monica Mntns. Res. ' Chickering American River Reserve Merced Vernal Pools & Grassland Res. Sweeney Granite Mountains DRC ' Coal Oil Point Natural Reserve Motte Rimrock Reserve VESR – Sierra Nevada Aquatics Res Lab ' Dawson Los Monos Reserve Kenneth S. Norris Rancho Marino Res. VESR – Valentine Camp ' Elliott Chaparral Reserve Quail Ridge Reserve White Mountain Research Center ' Emerson Oaks Reserve Sagehen Creek Field Station Younger Lagoon Reserve ' ' How'is'the'use'of'NRS'reserve(s)'important'to'your'project?' ' ' ' ' ' ' ' BUDGET' Funding may be requested for: necessary supplies and minor equipment; reserve user fees; actual cost of food and travel to, from and at the reserve; special logistical costs; computer support; access to special analytical equipment, etc. -

Federal Register June 24,1997 Tuesday Office (GPO)

6±24±97 Tuesday Vol. 62 No. 121 June 24, 1997 Pages 33971±34156 Now Available Online Code of Federal Regulations via GPO Access (Selected Volumes) Free, easy, online access to selected Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) volumes is now available via GPO Access, a service of the United States Government Printing Office (GPO). CFR titles will be added to GPO Access incrementally throughout calendar years 1996 and 1997 until a complete set is available. GPO is taking steps so that the online and printed versions of the CFR will be released concurrently. The CFR and Federal Register on GPO Access, are the official online editions authorized by the Administrative Committee of the Federal Register. New titles and/or volumes will be added to this online service as they become available. http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr For additional information on GPO Access products, services and access methods, see page II or contact the GPO Access User Support Team via: ★ Phone: toll-free: 1-888-293-6498 ★ Email: [email protected] federal register 1 II Federal Register / Vol. 62, No. 121 / Tuesday, June 24, 1997 SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES PUBLIC Subscriptions: Paper or fiche 202±512±1800 Assistance with public subscriptions 512±1806 General online information 202±512±1530; 1±888±293±6498 FEDERAL REGISTER Published daily, Monday through Friday, (not published on Saturdays, Sundays, or on official holidays), Single copies/back copies: by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Paper or fiche 512±1800 Records Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Assistance with public single copies 512±1803 Register Act (49 Stat. -

California Institute of of Wireless Networked, Durable, Low- Technology Power, Terrestrial and Aquatic In-Situ Sensing Systems

University of California Natural Reserve System Special Research Projects National Centers & Other Landscape-scale Projects that Utilize NRS Reserves The UC Natural Reserve System plays an enabling role in major research projects that are of nationwide significance. By providing protected, landscape- scale locales, as well as support facilities, dedicated to research, these sites attract specialists in a wide diversity of fields ranging from ecology, engineering, and marine biology to computer Interdisciplinary teams science, geology, and forestry. of researchers working at NRS reserves are The UC Natural Reserve System provides unmatched research opportunities. developing systems Over two thousand researchers from the University of California, as well as from many other institutions across the country and around the world, cur- and techniques that rently work on hundreds of research projects on NRS reserves. will lead to the next generation of scientific This compendium highlights fifteen large-scale investigations that involve collaborative efforts of interdisciplinary teams of scientists from multiple breakthroughs. institutions in research that is part of a larger national or international effort. These projects all aim at gaining more complete understanding of the basic physical and ecological processes that govern the functioning of the biosphere. Such understanding is critically important to the sustainable wise management of natural resources, whether they be terrestrial or marine. The list includes national centers funded by the National Science Foundation, as well as landscape-scale projects funded by both federal agencies and private foundations. Addressing today’s global environmental problems requires that scientists work together in new ways, employing new tools, and on a scale that was unimaginable just a few years ago. -

Obfs Annual Report 2011

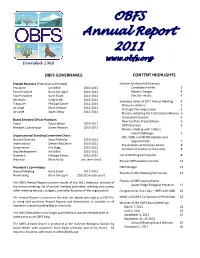

OOBBFFSS AAnnnnuuaall RReeppoorrtt 22001111 www.obfs.org Founded 1968 Founded 1968 OBFS GOVERNANCE CONTENT HIGHLIGHTS Elected Positions (Executive Committee) Election for Board of Directors President Ian Billick 2010‐2012 Candidate Profiles 2 Past President Brian Kloeppel 2010‐2012 Bylaws Changes 4 Vice President Karie Slavik 2011‐2013 Election results 4 Secretary Greg Smith 2010‐2012 Secretary notes of 2011 Annual Meeting 4 Treasurer Philippe Cohen 2011‐2013 Welcome Address 4 At‐Large Mark Schulze 2011‐2013 Strategic Planning Session 5 At‐Large Sarah Oktay 2010‐2012 Plenary: Adapting the Field Station Mission 5 Concurrent Sessions 6 Board Selected Officer Positions New Facilities Presentations 6 Editor David White 2010‐2012 OBFS Business 6 Network Coordinator Gwen Pearson 2010‐2012 Plenary: Dealing with Today’s Fiscal Challenges 7 Organizational Standing Committee Chairs NSF, FSML and NEON Updates and Human Diversity Stacy McNulty 2010‐2012 Opportunities 7 International Deedra McClearn 2010‐2012 Presentation of Diversity Award 8 Governance Eric Nagy 2010‐2012 Concurrent Sessions (continued) 8 Org Development Ian Billick 2010‐2012 Outreach Philippe Cohen 2010‐2012 List of Meeting Participants 8 Historian Mary Hufty (no term limit) Annual OBFS Auction Income 13 President’s Committees OBFS Budget 13 Annual Meeting Karie Slavik 2011‐2013 Results of 2011 Meeting Exit Survey 14 Nominating Brian Kloeppel 2011 (Calendar year) The OBFS Annual Report contains results of the 2011 elections, minutes of Friends of OBFS Special Event Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve 21 the annual meeting, list of annual meeting attendees, meeting exit survey, other meeting minutes, budgets, and other business of the organization. Congressional Visits Day – OBFS with AIBS 22 The Annual Report is posted on the web site (www.obfs.org) as a PDF file. -

Desert Fever: an Overview of Mining History of the California Desert Conservation Area

Desert Fever: An Overview of Mining History of the California Desert Conservation Area DESERT FEVER: An Overview of Mining in the California Desert Conservation Area Contract No. CA·060·CT7·2776 Prepared For: DESERT PLANNING STAFF BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR 3610 Central Avenue, Suite 402 Riverside, California 92506 Prepared By: Gary L. Shumway Larry Vredenburgh Russell Hartill February, 1980 1 Desert Fever: An Overview of Mining History of the California Desert Conservation Area Copyright © 1980 by Russ Hartill Larry Vredenburgh Gary Shumway 2 Desert Fever: An Overview of Mining History of the California Desert Conservation Area Table of Contents PREFACE .................................................................................................................................................. 7 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................... 9 IMPERIAL COUNTY................................................................................................................................. 12 CALIFORNIA'S FIRST SPANISH MINERS............................................................................................ 12 CARGO MUCHACHO MINE ............................................................................................................. 13 TUMCO MINE ................................................................................................................................ 13 PASADENA MINE -

Exploring Home: a Recreational Day Use and Interpretive Trail at Putah Creek Exploring Home: a Recreational Day Use and Interpretive Trail for Putah Creek

Exploring Home: A Recreational Day Use and Interpretive Trail at Putah Creek Exploring Home: A Recreational Day Use and Interpretive Trail for Putah Creek Sage Millar Senior Project June 2008 University of California, Davis Department of Environmental Sciences Landscape Architecture Program A Senior Project Presented to the Faculty of the Landscape Architecture program University of California,Davis in fulfillment of the Requirement Exploring Home: for the Degree of A Recreational Day Use and Interpretive Bachelors of Science of Landscape Architecture Trail for Putah Creek Rob Thayer, Senior Project Advisor Presented by: Patsy Owens, Senior Project Advisor Sage Millar at University of California, Davis Steve McNeil, Committee Member on the Thirteenth day of June, 2008 This senior project consists of background research and site analysis as well as a final site plan for a recreational day use area and interpretive trail on Putah Creek. This document contains the background research, site analysis, and program develop- Abstract ment I completed before designing the final site plan. The site is 10 miles west of Winters on Hwy 128 at the base of Monticello Dam where Cold Creek enters Putah Creek. The site is in the Pu- tah Creek Wildlife area and is approximately 25 acres. Because of it’s location near the trailhead into Stebbins Reserve, and Putah and Cold Creeks, the site provides and excellent opportunity to create an educational and interpretive experience for visitors to the area. Hiking trails, informational kiosks and signage will highlight the history and various natural processes that are occur- ring on and around the site. A small interpretive center or outdoor teaching area will enhance the experience of visitors, and also provide an outdoor classroom for gatherings such as field trips. -

Natural Reserve System Map Flyer

Natural Reserve System Natural Reserve System UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA university of california 1111 Franklin St., 6th Floor Oakland, CA 94607-5200 The UC Natural Reserve System provides a nrs.ucop.edu library of ecosystems throughout California. Reserves offer outdoor laboratories to field scientists, classrooms without walls for students, and nature’s inspiration to all. Founded in 1965 to provide a network of wildland sites available for scientific study, the NRS has grown to include more than 40 locations encompassing more than 756,000 acres across the state. The NRS is the world’s largest university- Reserves are listed by administering campus operated system of natural reserves; no Berkeley Los Angeles San Diego other network of field sites can match its 1 Angelo Coast Range Reserve 15 Stunt Ranch Santa Monica 25 Dawson Los Monos LOBSANG WANGDU size, scope, and ecological diversity. 2 Blue Oak Ranch Reserve Mountains Reserve Canyon Reserve 3 Chickering American River Reserve 16 White Mountain Research Center 26 Elliott Chaparral Reserve 4 Hastings Natural History Merced 27 Kendall-Frost Mission Bay Reservation Marsh Reserve Sierra Nevada Research Stations: 5 Jenny Pygmy Forest Reserve 28 Scripps Coastal Reserve 17 Merced Vernal Pools and 6 Sagehen Creek Field Station Grassland Reserve Santa Barbara 29 Carpinteria Salt Marsh Reserve Davis 18 Yosemite Field Station 30 Coal Oil Point Natural Reserve 7 Bodega Marine Reserve Riverside 31 Kenneth S. Norris Rancho 8 Jepson Prairie Reserve 19 Box Springs Reserve Marino Reserve 9 McLaughlin