'Translating the Subaltern' : a Study of Sara Joseph's Ramayana Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Department of English MA English Course Plan 2018

SACRED HEART COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) Department of English MA English Course Plan 2018 – 19 Semester IV COURSE PLAN PROGRAMME MA ENGLISH SEMESTER 4 COURSE CODE AND 16P4ENGT16 - LITERATURE AND THE CREDIT 4 TITLE EMPIRE HOURS/WEEK 5 HOURS/SEM 90 FACULTY NAME DR. JOSEPH VARGHESE COURSE OBJECTIVES To identify the complexity of origin and development of the terminology specific to colonial and postcolonial discourses. To understand the depth and the diverse genres of postcolonial literature. To explore the discursive nature of colonialism, and the counter-discursive impulses of postcolonial theory, narratives and performance texts. To compare and contrast the issues, conflicts, preoccupations, and themes of the various post-colonial literature To critically analyse the theoretical practices based on the colonial experience and the writers’ attempt to free from colonial domination. To describe the major features of postcolonial writings and the creation and exploitation of the “other” worlds, and multiple gender repression visualized in the writing of select writings. LEARNING VALUE SESSION TOPIC REMARKS RESOURCES ADDITIONS MODULE I 1 General Introduction – Literature and PPT/Lecture video the Empire 2 Bill Ashroft, Gareth Griffiths and Helen PPT/Lecture Tiffin: Cutting the Ground: Critical Models of Post- Colonial Literatures” in the in The Empire Writes Back: Theory and Practice in Post-Colonial Literatures. Routledge, 1989. (Chapter 1 PP.15-37) 3 Bill Ashroft, Gareth Griffiths and Helen PPT/Lecture Tiffin: Cutting the Ground: Critical Models of Post- Colonial Literatures” in the in The Empire Writes Back: Theory and Practice in Post-Colonial Literatures. Routledge, 1989. (Chapter 1 PP.15-37) 4 Bill Ashroft, Gareth Griffiths and Helen PPT/Lecture E-resource Tiffin: Cutting the Ground: Critical Models of Post- Colonial Literatures” in the in The Empire Writes Back: Theory and Practice in Post-Colonial Literatures. -

Debunking Orthodoxy in Kamala Das' the Sandal

PSYCHOLOGY AND EDUCATION (2021) 58(4): 3300-3306 ISSN:00333077 DEBUNKING ORTHODOXY IN KAMALA DAS’ THE SANDAL TREES AND SARA JOSEPH’S THE SCENT OF THE OTHER SIDE Dr. S. Devika Associate Professor, English, HHMSPBNSS College for Women, Neeramankara, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India ABSTRACT: The two Malayalam novels discussed in this paper tell tales of women’s transgressions. It is a transgression of a sexual nature that forms the theme of Kamala Das’ The Sandal Trees and Sara Joseph’s The Scent of the Other Side; in the case of the latter, the violation strikes at the very core of the Roman Catholic religion as it is practised in Kerala. In both the Malayalam novels, the transgressions that challenge and resist the power structures in society, be they of caste, religion, marriage or gender, provoke strong reactions from the dominant power groups who seek to oppress and subdue the violators and to reinforce the norms of orthodoxy. This study primarily attempts to put in perspective the mapping of Kerala in fiction, with reference to the gender question. Keywords: Malayalam fiction, transgression, orthodoxy, female psyche, resistance, stoicism Article Received: 18 October 2020, Revised: 3 November 2020, Accepted: 24 December 2020 The modern state of Kerala on the western coast its sobriquet “God’s Own Country,” but to the of the Indian Union, which lies to the west of Malayali it is an intrinsic part of his consciousness Tamil Nadu and southwest of Karnataka came and identity, defining his habits, customs, rituals into existence with the unification of the provinces and mode of life in ways that have cultural, social, of Travancore, Cochin and Malabar on November economic, even political ramifications. -

MA-English-2019.Pdf

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Curriculum and Syllabus for Postgraduate Programme in English Under Credit Semester System (with effect from 2019 admissions) ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I place on record my heartfelt gratitude to the members of the Board of Studies, Department of English, for their cooperation and valuable suggestions. I acknowledge their sincere efforts to scrutinize the draft curriculum and make necessary corrections. Dr. Sabu Joseph Chairman Board of Studies BOARD OF STUDIES CHAIRMAN NAME OFFICIAL ADDRESS Dr Sabu Joseph Associate Professor Department of English St Berchmans College Changanacherry - 686101 SUBJECT EXPERTS NOMINATED BY THE COLLEGE ACADEMIC COUNCIL NAME OFFICIAL ADDRESS Dr Vinod V Balakrishnan Professor of English Department of Humanities and Social Sciences National Institute of Technology Tiruchirappalli- 620015 Dr Babu Rajan P P Assistant Professor Department of English Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit Kalady EXPERT NOMINATED BY THE VICE-CHANCELLOR NAME OFFICIAL ADDRESS Dr K M Krishnan Director, School of Letters M G University, Kottayam ALUMNI REPRESENTATIVE NAME OFFICIAL ADDRESS Dr. Rekha Mathews Associate Professor and Head B K College, Amalagiri MEDIA AND ALLIED AREAS NAME OFFICIAL ADDRESS Dr Paul Manalil Former Director Kerala State Institute of Children’s Literature and Former Assistant Editor, Malayala Manorama TEACHERS FROM THE DEPARTMENT NOMINATED BY THE PRINCIPAL TO THE BOARD OF STUDIES TEACHER’S NAME AREA OF SPECIALISATION Josy Joseph Shakespeare Studies, Literary Theory Dr Benny Mathew Indian Writing -

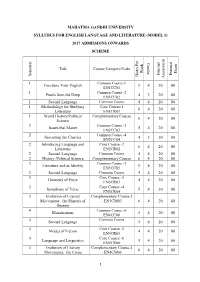

Mahatma Gandhi University Syllubus for English Language and Literature (Model 1) 2017 Admissions Onwards

MAHATMA GANDHI UNIVERSITY SYLLUBUS FOR ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE (MODEL 1) 2017 ADMISSIONS ONWARDS SCHEME Credits Title Course Category/Code Week Exam Internal Internal External External Semester Hours Per Hours Assessment 1 Common Course-1 Fine-tune Your English 5 4 20 80 EN1CC01 1 Common Course -2 Pearls from the Deep 4 3 20 80 EN1CC02 1 Second Language Common Course 4 4 20 80 1 Methodology for Studying Core Course-1 6 4 20 80 Literature EN1CR01 1 World History/Political Complementary Course 6 4 20 80 Science 2 Common Course -3 Issues that Matter 5 4 20 80 EN2CC03 2 Common Course -4 Savouring the Classics 4 3 20 80 EN2CC04 2 Introducing Language and Core Course -2 6 4 20 80 Literature EN2CR02 2 Second Language Common Course 4 4 20 80 2 History /Political Science Complementary Course 6 4 20 80 3 Common Course -5 Literature and/as Identity 5 4 20 80 EN3CC05 3 Second Language Common Course 5 4 20 80 3 Core Course -3 Harmony of Prose 4 4 20 80 EN3CR03 3 Core Course -4 Symphony of Verse 5 4 20 80 EN3CR04 3 Evolution of Literary Complementary Course 3 Movements: the Shapers of - EN3CM03 6 4 20 80 Destiny 4 Common Course -6 Illuminations 5 4 20 80 EN4CC06 4 Common Course Second Language 5 4 20 80 4 Core Course -5 Modes of Fiction 4 4 20 80 EN4CR05 4 Core Course -6 Language and Linguistics 5 4 20 80 EN4CR06 4 Evolution of Literary Complementary Course 4 6 4 20 80 Movements: the Cross - EN4CM04 1 Currents of Change 5 EN5CROP01 Appreciating Films EN5CROP02 Open Course 4 3 20 80 Theatre Studies EN5CROP03 English for Careers 5 Core Course -

Vol VIII Isue 1-4.Pmd

ISSN 2249-9873 Tapasam A Quarterly Journal for Kerala Studies Adn-bm\pw Xm]kw in Malayalam - English Adn-bn-°m\pw TAPTAPASAMASAM Vol: VIII / Issue 1-4 / July 2012 - April 2013 / Reg. No: M2 11257/ 05 V. J. Varghese Hybrid Assemblages: Modernity and Exceptionalism of Kerala.............. 1 Anna Lindberg Modernization and Religious Identities in Late Colonial Madras and Malabar.... 8 Amali Philips Endogamy Revisited Marriage and Dowry among the Knanaya Syrian Christians of Kerala.............36 Aparna Nair Magic Lanterns, Mother-craft and School Medical Inspections: Fashioning Modern Bodies and Identities in Travancore...... 60 Navaneetha Mokkil Remembering the Prostitute: Unsettling Imaginations of Sexuality.....................86 Jenson Joseph Revisiting Neelakkuyil: On the Left's cultural vision, Malayali nationalism and the questions of 'regional cinema'.................................................114 Shalini Moolechalil Recasting the Marginalised: Reading Sarah Joseph's Ramayana Stories in the Context of the Dravidian Movement..........145 T tcJm-ti-J-c-Øn¬\n∂v AP thWp-tKm-]m-e-∏-Wn°¿ `mjm-N¿® - ASAM, -s{]m^. F¬. hn. cma-kzmanAø¿.................... 172 V Kth-j-W-cwKw ol. VIII, Issues 1-4, 2013 kvIdnbm k°-dnb alm-`m-K-hXw Infn-∏m-´nse Zi-a-kvI‘w ˛ kwtim-[n-X-kw-kvI-cWw cLp-hmkv F.hn./tUm.]n.-Fw. hnP-b-∏≥...........174. ]pkvX-I-]q-cWw kvIdnbm k°-dnb amXr-`m-j-bv°p th≠n-bp≈ kacw ]n. ]hn-{X≥..............................................................177 Issue Editor: Dr V. J. Varghese 1 2 TAPASAM, Vol. VIII, Issues 1-4, 2013 Hybrid Assemblages: Modernity and Exceptionalism of Kerala Partha Chatterjee’s refusal to subscribe to the formulation of Benedict Anderson on nation, as a western normative import to non-western contexts, has also significantly debunked universal biographies of modernity. -

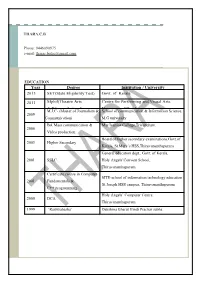

THARA.C.B Phone: 9446090975 E-Mail: [email protected] EDUCATION Year Degree Institution / University 2013 SET(State Eligibi

THARA.C.B Phone: 9446090975 e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION Year Degree Institution / University 2013 SET(State Eligibility Test) Govt. of Kerala 2011 Mphil(Theatre Arts Centre for Performing and Visual Arts, & Film aesthetics for University of Kerala M.J.C- (Master of Journalism & School of communication & Information Science, 2009 Communication) M.G university BA Mass communication & Mar Ivanios College,Trivandrum. 2006 Video production Board of higher secondary examinations,Govt.of 2003 Higher Secondary Kerala, St.Mary’s HSS,Thiruvananthapuram General education dept., Govt. of Kerala, 2001 SSLC Holy Angels’Convent School, Thiruvananthapuram Certificate course in Computer SITE-school of information technology education 2001 Fundamentals & St.Joseph HSS campus, Thiruvananthapuram C++ programming Holy Angels’ Computer Centre, 2000 DCA Thiruvananthapuram 1999 ‘Rashtrabasha’ Dakshina Bharat Hindi Prachar sabha EXPERIENCE IN PRINT MEDIA : Freelancing - Snehitha (keralakaumudi publication)- campus page -The hindu-Metro - The New Indian Express - Janmabhumi daily ARTS - ON STAGE: DANCE Practicing dances (Bharathanatyam, Mohiniyattam,Kuchipudi , Kathakali & folk dances since 1989 Specialization: Mohiniyattam Compositions: Swathithirunal Padam fusion (Aliveni,Alarsara & Kaminimani), Othello in Mohiniyattam, fusion of poems’Krishna nee enne ariyilla’of Smt.Sugathakumari &’Gopika dandakam’of Sri Ayyappa Paniker,Omanathingal in Mohiniyattam, Play’ Rithumathi’by M.P Bhattathirippad as dance drama, ‘Thaikulam’ of Sarah Joseph in Mohiniyattam. -

Coexistence of Culture and Nature in Gift in Green by Sarah Joseph S

======================================================================= Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 18:10 October 2018 R. Rajalakshmi, Editor: Select Papers Presented in the Conference Reading the Nation – The Global Perspective St. Joseph’s College for Women, Tirupur, Tamilnadu ======================================================================= Coexistence of Culture and Nature in Gift in Green by Sarah Joseph S. Krithika Devi ===================================================================== “The struggle forged by men at work, by men and women joined in harmony in the struggle against nature was the basic theme of all the mythologies of human life” (Rickward 130 - 131) Culture and nature may be contradictory terms in the modern sense. But the relationship between man and nature are not just interdependent but also interrelated. The regional topography plays a major role to construct a culture in a community. It is usually believed that the ethnic groups are not civilized. They are not aware of the development that is going on in the outside world. But the truth is that they are living a self-sustainable lifestyle that helps them to avoid depending on the outside sources. The human activities was molded in such a way that it co-exist with the nature. Their culture is constructed by interweaving nature and human activities. This eco spiritual life style gives the myths, legends, gods, values, and songs. So the dependence is not needed for the ingenious community. Sarah Joseph, novelist and short story writer of Malayalam, was born in a conservative Christian family at Kuriachira in Trissur city in 1946. Her father, Louis was inclined to Marxian ideology and her mother Kochumariam was a typical conservative Christian type house wife. -

University of Pondicherry U.G

UNIVERSITY OF PONDICHERRY U.G. BOARD (MALAYALAM) SYLLABUS FOR B.Com, B.A. / B.Sc.. FOUNDATION COURSE AND B.A.MALAYALAM (Effective from 2010 Admission) MINUTES OF THE MEETING DIVISION OF SYLLABUS DETAILED SYLLABUS FOR FOUNDATION COURSE DETAILED SYLLABUS FOR BA.MALAYALAM – CORE AND ALLIED SCHEME OF QUESTION PAPERS MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE BOARD OF STUDIES (U.G.MALAYALAM) (Meeting held on 06-04-2010 at 10.30 A.M in the Seminar hall, Dept. of Malayalam, M.G.Govt. Arts College,Mahe) Members and special invitees present 1) Dr.V.Sarathchandran Nair, Principal,S.R.L.C, Central Institute of Indian Languages,Mysore-6 2) Dr.P.Pavithran, Reader in Malayalam, Sree Sankaracharya Sanskrit University Centre,Thirur 3). Dr. V.A. Valsalan, Asociate Professor of Malayalam M.G.G Arts College, Mahe ( Chairman) 4). Dr. S.S. Sreekumar, Associate Professor of Malayalam , M.G.Govt. Arts College, Mahe. 5) Dr.Mahesh Mangalat,Associate Professor of Malayalam, M.G.Govt.Arts College, Mahe 6) Dr. K.M. Bharathan, Asst. Professor of Malayalam, M.G.G Arts College, Mahe. 7) Dr.K.K.Baburaj, Asst. Professor of Malayalam , M.G.G Arts College, Mahe 8) Mr.E.C.Sreesh, Asst. Professor of Malayalam, M.G.G Arts College, Mahe Proceedings: 1. The board reviewed the existing syllabus, pattern of question papers and list of textbooks. Necessary changes were effected in the syllabus, question papers and L.T.B. 2. The pattern of question paper and division of syllabus are appended herewith 3. The list of textbooks and unit wise divisions of syllabus is submitted herewith. -

Ecofeminism - Niji C

Ecoaesthetics and Literature ètude A Multidisciplinary Research Journal 1 Ecoaesthetics and Literature ètude - A Multidisciplinary Research Journal PUBLISHED IN INDIA BY The Coordinator, Internal Quality Assurance Cell (IQAC) ètude of the Panampilly Memorial Government College (PMGC) Chalakudy, Potta P.O., Thrissur District, Kerala, India. PIN 680722 A Multidisciplinary email: [email protected] / [email protected] Research Journal http://www.pmgc.ac.in © IQAC-PMGC 2015 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no production of any part may take place without the written permission of the Coordinator, IQAC, Panampilly Memorial Government College, Chalakudy, Kerala, India Published in January 2015 Managing Editor: Dr. Sreevalsa V.G., Principal Chief Editor: C.R. Murukan Babu, Coordinator, IQAC Editorial Board: K. Renuka, Dr. C. C. Babu, Dr. N. A. Jojomon, Dr. Dimpi Divakaran, Dr. B. Parvathy, Dr. N. Sreerekha, Dr. Leena Samuel Issue Editors: Dr. N. Sreerekha (English), Dr. B. Paravathy (Malayalam), Dr. Leena Samuel (Hindi) ISSN: 2394 - 6482 Etude Printed in India by Nirmala Offset Printers, Chalakudy, Kerala +91 480 2701259 Cover design & illustration by Rajiv Babu, CET, Kerala 1 2 Ecoaesthetics and Literature ètude A Multidisciplinary Research Journal Special Inaugural Edition on Ecoaesthetics and Literature Published by IQAC Panampilly Memorial Government College Chalakudy 3 Ecoaesthetics and Literature ètude - A Multidisciplinary Research Journal Contents ètude A Multidisciplinary FOREWORD 6 Research Journal PREFACE 7 SECTION ONE - ENGLISH 9 Introduction - Dr. N. Sreerekha 1. Eco Feminism - An overview - Dr. Prathibha 13 2. Revivifying Woman-Nature Equations: Politics in the Poems of Sugathakumari - Suja T. -

An Imprint of Harpercollins Publishers 1

@HarperCollinsIN An Imprint of HarperCollins Publishers 1 Let’s Talk Translation! Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, showcases the finest writing from the various languages of the Indian subcontinent in English translation. Here is a library of powerful writers and books that will go on to become classics; here is a wealth of writing in translation; here are stories, anti-stories, novels, poetry, political manifestos, travelogues and memoirs. Harper Perennial is as much about literature that is rooted, as it is about finding ways to make it travel. So, as an additional feature, every title comes with a P.S. Section that allows readers to explore the books more intimately through translator’s notes, essays and author interviews. 2 3 CELEBRATING 10 YEARS OF HARPER PERENNIAL IN INDIA FROM THE PUBLISHER'S DESK In 2017, Harper Perennial, a dedicated imprint for translations, completes ten years of publishing in India. Over the past decade, Perennial books have showcased the finest and most compelling narratives from the Indian languages, books that are timeless and stories that capture the essence of their times and the region from which they emanate. In its entirety, the Perennial library which features over a hundred titles presents the kaleidoscope of India as seen through the eyes of the greatest modern writers writing in the local languages, comprising award-winning and well-loved novels, short fiction, poetry, plays, memoirs, biographies and travelogues. Over the last few months, Harper Perennial has published a select list of titles in translation that readers will have enjoyed – including Gulzar’s first novel Two and his collection of Partition writings Footprints on Zero Line, Rabindranath Tagore’s The Boat-wreck, Kiran Nagarkar’s first novel Seven Sixes Are Forty-three, Ranjit Desai’s Shivaji: The Great Maratha, Pran Kishore’s Gul Gulshan Gulfam, Vinod Kumar Shukla’s Moonrise from the Green Grass Roof, Rahi Masoom Raza’s Scene: 75, and Jayant Kaikini’s book of Mumbai stories No Presents Please. -

Review of Research Impact Factor : 5.7631(Uif) Ugc Approved Journal No

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.7631(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 7 | issUe - 11 | aUGUst - 2018 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ ECOFEMINISM: RECOGNITION OF SELF EXISTENT IN OTHHAPPU: THE SCENT OF THE OTHER SIDE BY SARAH JOSEPH Anjali Daudbhai Parmar Ph.D Scholar, Asst. Prof. ABSTRACT The women of today need to seek the power within them. The present paper is an attempt to emphasize on the recognition of self existent, quest for identity,and struggle for survival of women in Otthappu: The Scent of the other side.Ecofeminism as an ideology and movement finds that the oppression of women is interlinked to the oppression of nature with the same masculine centered attitudes and practices concerning to the patriarchal society. Ecofeminism has its roots in literature also. As Carolyn Merchant points out, “We make by act trees and flowers to come earlier or later than their seasons, and to come up and bear more speedily than their natural course they do. We make them by act greater, much more than their nature, and their fruit greater and sweeter and of differing taste, smell, color and figure from their nature.” KEYWORDS: self existent, quest for identity , patriarchal society. INTRODUCTION: Thus nature came to be seen as more like a woman to be raped and even the violation of nature is linked with the violation of women. The protagonist of Sarah Joseph’s novel rightly gives the answer of Ayn Rand’s the question, isn’t who is going to let me; its’ who is going to stop me by their revolutionary steps throughout the novel.This paper will also examine the cultural and spiritual ecofeminism as ecofeminism is an ideology for the recognition of women, for the preservation of nature and for the sustenance of life on earth.