Ephesians and Ecumenism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Conversation with Christos Yannaras: a Critical View of the Council of Crete

In conversation with Christos Yannaras: a Critical View of the Council of Crete Andreas Andreopoulos Much has been said and written in the last few months about the Council in Crete, both praise and criticism. We heard much about issues of authority and conciliarity that plagued the council even before it started. We heard much about the history of councils, about precedents, practices and methodologies rooted in the tradition of the Orthodox Church. We also heard much about the struggle for unity, both in terms what every council hopes to achieve, as well as in following the Gospel commandment for unity. Finally, there are several ongoing discussions about the canonical validity of the council. Most of these discussions revolve around matters of authority. I have to say that while such approaches may be useful in a certain way, inasmuch they reveal the way pastoral and theological needs were considered in a conciliar context in the past, if they become the main object of the reflection after the council, they are not helping us evaluate it properly. The main question, I believe, is not whether this council was conducted in a way that satisfies the minimum of the formal requirements that would allow us to consider it valid, but whether we can move beyond, well beyond this administrative approach, and consider the council within the wider context of the spiritual, pastoral and practical problems of the Orthodox Church today.1 Many of my observations were based on Bishop Maxim Vasiljevic’s Diary of the Council, 2 which says something not only about the official side of the council, but also about the feeling behind the scenes, even if there is a sustained effort to express this feeling in a subtle way. -

What Is Ecumenism*?

What is Ecumenism*? From the Greek meaning “inhabited house.” A worldwide movement among Christians who accept Jesus as Lord and savior and, inspired by the Holy Spirit, seek through prayer, dialogue, and other initiatives to eliminate barriers and move toward the unity Christ willed for his church (Jn 17:21; see also Eph 4:4-5, UR 1-4). Christian communities separated over the Council of Ephesus (431), over the Council of Chalcedon (451), through the East-West schism conventionally dated 1054, at the Reformation in the sixteenth century, and later. Vatican II taught that the true church “subsists in” but is not simply identified with the Catholic Church (LG 8). Belief in Christ and baptism establish a real, if imperfect, union among all Christians (LG 15). In particular, the Orthodox share with Catholics very many elements of faith and sacramental life, including the Eucharist and apostolic succession (see OE 27-30). The Church Unity Octave, eight days of prayer for religious unity of all Christians, which is celebrated each year from January 17 to 25, was stared in 1908 by the founder of the Society of Atonement, Fr. Paul Wattson (1863-1940) when still a member of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States. The following year, with other friars, sisters, and laymen of his Graymoor community, he was received into the Catholic Church * From A Concise Dictionary of Theology. Eds. Gerald O’Collins, S.J. and Edward Farrugia, S.J. Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 2000. What is Interreligious Dialogue? First, interreligious dialogue can be described as a kind of “formal conversation” with persons of non- Christian faiths. -

An Ecumenical Journey

An Ecumenical Journey A timeline of the World Council of Churches The Netherlands 1948 Zimbabwe 1998 USA 1954 Canada 1983 Sweden 1968 Australia 1991 India 1961 Kenya 1975 Brazil 2006 General Secretaries of WCC W. A. Visser ’t Hooft (1900-1985) Philip Potter (1921-) Konrad Raiser (1938-) Olav Fykse Tveit (1960-) Term: 1938-1966 Term: 1972-1985 Term: 1993-2003 Term: 2010- A brilliant and visionary Christian leader from the A Methodist pastor, missionary and youth leader from A German theologian who served on the WCC staff under A pastor from the Lutheran communion, Tveit began his Netherlands, Willem Visser ’t Hooft was named WCC general Dominica in the West Indies, Potter was called to several Philip Potter, Raiser once described his ecumenical calling as term of office in January 2010 following seven years as secretary at the 1938 meeting in which the WCC’s process of positions in the WCC. During his mandate as general “a second conversion.” During a sometimes turbulent period leader of the Church of Norway’s council on ecumenical formation began. A Reformed minister, he emphasized the secretary, he insisted on the fundamental unity of Christian for the ecumenical movement, he led the Council as general and international relations. Bringing wide experience in importance of linking the ecumenical movement to enduring witness and Christian service and the correlation of faith secretary in a redefinition of its “Common Understanding inter-religious dialogue, Tveit had also served as co-chair manifestations of the church through the ages. In 1968 he and action. and Vision” and in a fundamental review of the participation of the Palestine Israel Ecumenical Forum core group was elected honorary president of the WCC by the fourth of Orthodox member churches. -

Religion and Innovation in Human Affairs (RIHA) Religion And

Religion and Innovation in Human Affairs (RIHA) Exploring the Role of Religion in the Origins of Novelty and the Diffusion of Innovation in the Progress of Civilizations Religion and Innovation: Naturalism, Scientific Progress, and Secularization Protestantism? Reflections in Advance of the 500th Anniversary of the Protestant Reformation ($75,000). Gordon College. PIs: Thomas Albert Howard (Gordon College) and Mark A. Noll (University of Notre Dame) With an eye on the approaching quincentennial, of the Protestant Reformation, the project has engaged in a fundamental inquiry into the historical significance of Protestantism, its heterogeneous trajectories of influence, and their relationship to forces of social innovation, political development, and religious change in the modern West and across the globe. The quincentennial of the Protestant Reformation in 2017 will bring into public view longstanding scholarly debates, interpretations and their revisions—along with lingering confessional animosities and more recent ecumenical overtures. For Western Christianity, a moment of historical recollection on this scale has not presented itself in recent memory. Acts of commemoration can be enlisted to reflect, shape, and introduce novel forces into history. They were not simply conduits or transmitters of the old, but definers and harbingers of the new. In this sense, we might view the past commemorations of the Reformation as being not unlike the sixteenth-century Reformation itself: a series of acts motivated by the desire of retrieval and restoration that, in the final analysis, left a legacy of profound change, disruption, and innovation in human history. Major Outputs: Books: • Howard, Thomas Albert. The Pope and the Professor: Pius IX, Ignaz von Döllinger, and the Quandary of the Modern Age (accepted, Oxford University Press) • Howard, Thomas A. -

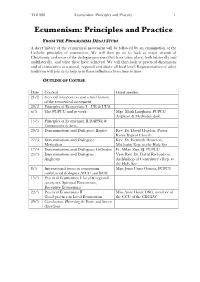

Ecumenism, Principles and Practice

TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 1 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice FROM THE PROGRAMMA DEGLI STUDI A short history of the ecumenical movement will be followed by an examination of the Catholic principles of ecumenism. We will then go on to look at major strands of Christianity and some of the dialogue processes that have taken place, both bilaterally and multilaterally, and what these have achieved. We will then look at practical dimensions and of ecumenism at national, regional and above all local level. Representatives of other traditions will join us to help us in these reflections from time to time. OUTLINE OF COURSE Date Content Guest speaker 21/2 General introduction and a brief history of the ecumenical movement 28/2 Principles of Ecumenism I – UR & UUS 6/3 The PCPCU and its work Mgr. Mark Langham, PCPCU Anglican & Methodist desk. 13/3 Principles of Ecumenism II DAPNE & Communicatio in Sacris 20/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Baptist Rev. Dr. David Hogdon, Pastor, Rome Baptist Church. 27/3 Denominations and Dialogues: Rev. Dr. Kenneth Howcroft, Methodists Methodist Rep. to the Holy See 17/4 Denominations and Dialogues: Orthodox Fr. Milan Zust SJ, PCPCU 24/4 Denominations and Dialogues : Very Rev. Dr. David Richardson, Anglicans Archbishop of Canterbury‘s Rep. to the Holy See 8/5 International issues in ecumenism, Mgr. Juan Usma Gomez, PCPCU multilateral dialogues ,WCC and BEM 15/5 Practical Ecumenism I: local & regional structures, Spiritual Ecumenism, Receptive Ecumenism 22/5 Practical Ecumenism II Miss Anne Doyle DSG, member of Good practice in Local Ecumenism the CCU of the CBCEW 29/5 Conclusion: Harvesting the Fruits and future directions TO1088 Ecumenism: Principles and Practice 2 Ecumenical Resources CHURCH DOCUMENTS Second Vatican Council Unitatis Redentigratio (1964) PCPCU Directory for the Application of the Principles and Norms of Ecumenism (1993) Pope John Paul II Ut Unum Sint. -

Neoconservatism: Origins and Evolution, 1945 – 1980

Neoconservatism: Origins and Evolution, 1945 – 1980 Robert L. Richardson, Jr. A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by, Michael H. Hunt, Chair Richard Kohn Timothy McKeown Nancy Mitchell Roger Lotchin Abstract Robert L. Richardson, Jr. Neoconservatism: Origins and Evolution, 1945 – 1985 (Under the direction of Michael H. Hunt) This dissertation examines the origins and evolution of neoconservatism as a philosophical and political movement in America from 1945 to 1980. I maintain that as the exigencies and anxieties of the Cold War fostered new intellectual and professional connections between academia, government and business, three disparate intellectual currents were brought into contact: the German philosophical tradition of anti-modernism, the strategic-analytical tradition associated with the RAND Corporation, and the early Cold War anti-Communist tradition identified with figures such as Reinhold Niebuhr. Driven by similar aims and concerns, these three intellectual currents eventually coalesced into neoconservatism. As a political movement, neoconservatism sought, from the 1950s on, to re-orient American policy away from containment and coexistence and toward confrontation and rollback through activism in academia, bureaucratic and electoral politics. Although the neoconservatives were only partially successful in promoting their transformative project, their accomplishments are historically significant. More specifically, they managed to interject their views and ideas into American political and strategic thought, discredit détente and arms control, and shift U.S. foreign policy toward a more confrontational stance vis-à-vis the Soviet Union. -

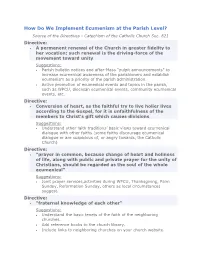

How Do We Implement Ecumenism at the Parish Level? Source of the Directives - Catechism of the Catholic Church Sec

How Do We Implement Ecumenism at the Parish Level? Source of the Directives - Catechism of the Catholic Church Sec. 821 Directive: A permanent renewal of the Church in greater fidelity to her vocation; such renewal is the driving-force of the movement toward unity Suggestions: Parish bulletin notices and after-Mass "pulpit announcements" to increase ecumenical awareness of the parishioners and establish ecumenism as a priority of the parish administration. Active promotion of ecumenical events and topics in the parish, such as WPCU, diocesan ecumenical events, community ecumenical events, etc. Directive: Conversion of heart, as the faithful try to live holier lives according to the Gospel, for it is unfaithfulness of the members to Christ's gift which causes divisions Suggestions: Understand other faith traditions’ basic views toward ecumenical dialogue with other faiths (some faiths discourage ecumenical dialogue or are suspicious of, or angry towards, the Catholic Church) Directive: "prayer in common, because change of heart and holiness of life, along with public and private prayer for the unity of Christians, should be regarded as the soul of the whole ecumenical" Suggestions: Joint prayer services,activities during WPCU, Thanksgiving, Palm Sunday, Reformation Sunday, others as local circumstances suggest. Directive: "fraternal knowledge of each other" Suggestions: Understand the basic tenets of the faith of the neighboring churches. Add reference books to the church library. Include links to neighboring churches on your church website. Directive: "ecumenical formation, of the faithful and especially of priests" Suggestions: For larger parishes, form an ecumenical and interreligious commission. For smaller parishes, appoint an appropriate person as the ecumenical & interfaith liaison. -

Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 104 Rev1 Page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 105 Rev1 Page 105

Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_103 rev1 page 103 part iii Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_104 rev1 page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_105 rev1 page 105 chapter five The Neoconservative Journey Jacob Heilbrunn The Neoconservative Conspiracy The longer the United States struggles to impose order in postwar Iraq, the harsher indictments of the George W. Bush administration’s foreign policy are becoming. “Acquiring additional burdens by engag- ing in new wars of liberation is the last thing the United States needs,” declared one Bush critic in Foreign Affairs. “The principal problem is the mistaken belief that democracy is a talisman for all the world’s ills, and that the United States has a responsibility to promote dem- ocratic government wherever in the world it is lacking.”1 Does this sound like a Democratic pundit bashing Bush for par- tisan gain? Quite the contrary. The swipe came from Dimitri Simes, president of the Nixon Center and copublisher of National Interest. Simes is not alone in calling on the administration to reclaim the party’s pre-Reagan heritage—to abandon the moralistic, Wilsonian, neoconservative dream of exporting democracy and return to a more limited and realistic foreign policy that avoids the pitfalls of Iraq. 1. Dimitri K. Simes, “America’s Imperial Dilemma,” Foreign Affairs (Novem- ber/December 2003): 97, 100. Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_106 rev1 page 106 106 jacob heilbrunn In fact, critics on the Left and Right are remarkably united in their assessment of the administration. Both believe a neoconservative cabal has hijacked the administration’s foreign policy and has now overplayed its hand. -

Synodality” – Results and Challenges of the Theological Dialogue Between the Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church

“SYNODALITY” – RESULTS AND CHALLENGES OF THE THEOLOGICAL DIALOGUE BETWEEN THE ORTHODOX CHURCH AND THE CATHOLIC CHURCH Archbishop Job of Telmessos I. The results of the Joint International Commission for the Theological Dialogue between the Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church The Joint International Commission for the Theological Dialogue between the Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church has been focusing on the topic of “Primacy and Synodality” over the last twelve years. This is not surprising, since the issue of the exercise of papal primacy has been an object of disagreement between Orthodox and Catholics over a millennium. The Orthodox contribution has been to point out that primacy and synodality are both inseparable: there cannot be a gathering (synodos) without a president (protos), and no one cannot be first (protos) if there is no gathering (synodos). As the Metropolitan of Pergamon, John Zizioulas, pointed out: “The logic of synodality leads to primacy”, since “synods without primates never existed in the Orthodox Church, and this indicates clearly that if synodality is an ecclesiological, that is, dogmatical, necessity so must primacy [be]”1. The Ravenna Document (2007) The document of the Joint International Commission for the Theological Dialogue between the Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church, referred as the “Ravenna Document” (2007), speaks of synodality and conciliarity as synonyms, “as signifying that each member of the Body of Christ, by virtue of baptism, has his or her place and proper responsibility in eucharistic koinonia (communio in Latin)”. It then affirms that “conciliarity reflects the Trinitarian mystery and finds therein its ultimate foundation”2 and from there, considers that “the Eucharist manifests the Trinitarian koinônia actualized in the faithful as an organic unity of several members each of whom has a charism, a service or a proper ministry, necessary in their variety and diversity for the edification of all in the one ecclesial Body of Christ”3. -

Supporting Papers for the Faith and Order Commission Report, Communion and Disagreement

SUPPORTING PAPERS FOR THE FAITH AND ORDER COMMISSION REPORT, COMMUNION AND DISAGREEMENT 1 Copyright © The Archbishops’ Council 2016 2 Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................................. 5 1 Communion, Disagreement and Conscience Loveday Alexander and Joshua Hordern ........................................................................................ 6 Listening to Scripture ..................................................................................................................... 6 Conscience: Points of Agreement ................................................................................................ 9 Conscience and Persuasion in Paul – Joshua Hordern .......................................................... 10 Further Reflections – Loveday Alexander .................................................................................. 15 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................................ 17 2 Irenaeus and the date of Easter Loveday Alexander and Morwenna Ludlow ................................................................................ 19 Irenaeus and the Unity of the Church – Loveday Alexander ................................................ 19 A Response – Morwenna Ludlow.................................................................................................. 23 Further Reflections – Loveday -

Ekklesia and Ecumenism in the Body of Christ: Unity from the Ground-Up

religions Article Ekklesia and Ecumenism in the Body of Christ: Unity from the Ground-Up Anastasia Wendlinder Gonzaga University, 502 East Boone Avenue, Spokane, WA 99258-0102, USA; [email protected] Received: 9 October 2018; Accepted: 22 November 2018; Published: 28 November 2018 Abstract: This article explores the implications for Christian unity from the perspective of the lived faith community, the ekklesia. While bilateral and multilateral dialogues have borne great fruit in bringing Christian denominations closer together, as indeed it will continue to do so, considering how the ecclesiological identity of the faith community both forms and reflects its members may be helpful in moving forward in our ecumenical efforts. This calls for a ground-up approach as opposed to a top-down approach. By “ground-up” it is meant that the starting point for theological reflection on ecumenism begins not with doctrine but with praxis, particularly as it relates to the common believer in the pew. The ecclesiological model “Body of Christ” provides a helpful vocabulary in this exploration for a number of reasons, none the least that it is scripturally-based, presumes diversity and employs concrete imagery relating to everyday life. Further, “Body of Christ” language is used by numerous Christian denominations in their statements of self-identity, regardless of where they lie on the doctrinal or political spectrum. In this article, potential benefits and challenges of this ground-up perspective will be considered, and a way forward will be proposed to promote ecumenical unity across denomination borders. Keywords: ecumenism; ecumenical; ecclesiology; ekklesia; body of Christ; Christianity; denomination; unity-in-diversity; bilateral dialogue; ressourcement; aggiornamento 1. -

THE JESUIT MISSION to CANADA and the FRENCH WARS of RELIGION, 1540-1635 Dissertation P

“POOR SAVAGES AND CHURLISH HERETICS”: THE JESUIT MISSION TO CANADA AND THE FRENCH WARS OF RELIGION, 1540-1635 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Joseph R. Wachtel, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Professor Alan Gallay, Adviser Professor Dale K. Van Kley Professor John L. Brooke Copyright by Joseph R. Wachtel 2013 Abstract My dissertation connects the Jesuit missions in Canada to the global Jesuit missionary project in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries by exploring the impact of French religious politics on the organizing of the first Canadian mission, established at Port Royal, Acadia, in 1611. After the Wars of Religion, Gallican Catholics blamed the Society for the violence between French Catholics and Protestants, portraying Jesuits as underhanded usurpers of royal authority in the name of the Pope—even accusing the priests of advocating regicide. As a result, both Port Royal’s settlers and its proprietor, Jean de Poutrincourt, never trusted the missionaries, and the mission collapsed within two years. After Virginia pirates destroyed Port Royal, Poutrincourt drew upon popular anti- Jesuit stereotypes to blame the Jesuits for conspiring with the English. Father Pierre Biard, one of the missionaries, responded with his 1616 Relation de la Nouvelle France, which described Port Royal’s Indians and narrated the Jesuits’ adventures in North America, but served primarily as a defense of their enterprise. Religio-political infighting profoundly influenced the interaction between Indians and Europeans in the earliest years of Canadian settlement.