You Cannot Do That Ben Stokes: Dynamically Predicting Shot Type in Cricket Using a Personalized Deep Neural Network

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

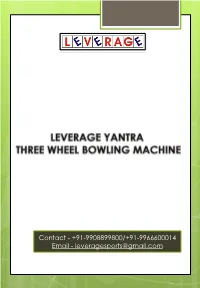

+91-9908899800/+91-9966600014 Email - [email protected] SACHIN TENDULKAR COMMENTS on LEVERAGE BOWLING MACHINES

Contact - +91-9908899800/+91-9966600014 Email - [email protected] SACHIN TENDULKAR COMMENTS ON LEVERAGE BOWLING MACHINES Contact - +91-9966600014 or +91-9908899800 RAHUL DRAVID COMMENTS ON LEVERAGE BOWLING MACHINES Contact - +91-9966600014 or +91-9908899800 A COMPUTERIZED THREE WHEEL CRICKET BOWLING MACHINE LEVERAGE YANTRA THREE WHEEL BOWLING MACHINE FEATURES: Speed – up to 170 Digital Operations MECHANICS kmph High Bounce Computerized Three Wheel Profile operations with Optimum bounce Criptex software Polyurethane wheels Low Bounce Pre-set variations Concave profile for In Swing the wheels. Specialty Variations Out Swing SEAM -GRIP technology Leg spin Programming Mode Hard and Cricket Off Spin Balls Usage Random Mode Flipper Regenerative Ready Indicator breaking system Top Spin Speed Indicator Head Cover for In swing-seam out safety Out Swing seam-in Video Analysis Micro Adjustment Software System Googly Robotic Alignment Wrong-un Battery Backup BOWLING VARIATIONS DIGITAL & PC OPERATIONS THREE WHEEL DESIGN Third wheel acts as thumb. Grip on the ball - In three wheel bowling machine grip on the ball is more due to 3 point contact of the wheels. Control Over the Ball - Having most of the surface of ball gripped, control over the ball is more compared to that in two wheel machines. Create Different Angles –Head position of the three wheel bowling machine needs no change to create right arm and left arm bowling angles ( In two wheel machines head has to be tilted manually sideways to get the desired angles). Fully covered wheels for safety Open wheels are dangerous. Hence Leverage Yantra has wheels with strong and robust outer cover. Player Benefits Numerous Variations produced by three wheel bowling machine are close to a real bowler. -

P26 Layout 1

26 Sports Thursday, June 27, 2019 Chris Gayle says he is among West Indies greats Always cherish two decades playing for the West Indies: Gayle MANCHESTER: Chris Gayle says he deserves to be West Indies host India for two Tests, three ODIs considered alongside the greats of West Indies cricket and three Twenty20 internationals in August and but is refusing to set a definite date for his retirement. September and Gayle believes that might be the time The swashbuckling opener is still hoping the West to bow out. “Maybe a Test match against India and Indies can sneak into the World Cup semi-finals, with definitely play the ODIs against India. I won’t play the India next in line at Old Trafford today, but the odds T20s. That’s my plan after the World Cup,” said a smil- are stacked heavily against them. ing Gayle, who last played Test cricket in 2014. Jason Holder’s team began the tournament with a Gayle, who has amassed more than 10,000 runs in comprehensive seven-wicket win against Pakistan but ODIs, admitted winning the World Cup would have soon lost momentum and that remains their only victo- been the ideal end to his career. Barring a freak set of ry in six matches. Self-styled “Universe Boss” Gayle, results, the two-time champions, who have three who hit 87 in his team’s heartbreaking five-run loss to games left, will be heading home before the semi- New Zealand on Saturday, said he would always cher- finals. ish his two decades playing for the West Indies. -

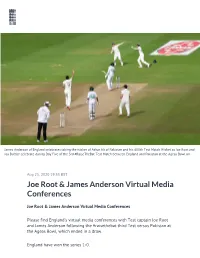

Joe Root & James Anderson Virtual Media Conferences

James Anderson of England celebrates taking the wicket of Azhar Ali of Pakistan and his 600th Test Match Wicket as Joe Root and Jos Buttler celebrate during Day Five of the 3rd #RaiseTheBat Test Match between England and Pakistan at the Ageas Bowl on Aug 25, 2020 19:33 BST Joe Root & James Anderson Virtual Media Conferences Joe Root & James Anderson Virtual Media Conferences Please find England’s virtual media conferences with Test captain Joe Root and James Anderson following the #raisethebat third Test versus Pakistan at the Ageas Bowl, which ended in a draw. England have won the series 1-0. You will find the following files: -Video and audio file of Joe Root and James Anderson’s media conferences – DOWNLOAD HERE Please credit - England and Wales Cricket Board. England Test Squad: Joe Root (Yorkshire) Captain, James Anderson (Lancashire), Jofra Archer (Sussex), Dominic Bess (Somerset), Stuart Broad (Nottinghamshire), Rory Burns (Surrey), Jos Buttler (Lancashire), Zak Crawley (Kent), Sam Curran (Surrey), Ollie Pope (Surrey), Ollie Robinson (Sussex), Dom Sibley (Warwickshire), Chris Woakes (Warwickshire), Mark Wood (Durham). Ends #raisethebat Three-match Test Series: 1st Test: England v Pakistan, 5-9 August, Emirates Old Trafford, Manchester (England win by three wickets) 2nd Test: England v Pakistan, 13-17 August, Ageas Bowl, Southampton (Match drawn) 3rd Test: England v Pakistan, 21-25 August, Ageas Bowl, Southampton (Match drawn) ____ You'll find all ECB Media Releases and associated resources on our Newsroom > Contacts Danny Reuben Press Contact Head of Team Communications England Men's team [email protected] +44 (0)7825 723 620. -

Will T20 Clean Sweep Other Formats of Cricket in Future?

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Will T20 clean sweep other formats of Cricket in future? Subhani, Muhammad Imtiaz and Hasan, Syed Akif and Osman, Ms. Amber Iqra University Research Center 2012 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/45144/ MPRA Paper No. 45144, posted 16 Mar 2013 09:41 UTC Will T20 clean sweep other formats of Cricket in future? Muhammad Imtiaz Subhani Iqra University Research Centre-IURC , Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 2010); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Amber Osman Iqra University Research Centre-IURC , Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 2010); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Syed Akif Hasan Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 1513); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Bilal Hussain Iqra University Research Centre-IURC , Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 2010); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Abstract Enthralling experience of the newest format of cricket coupled with the possibility of making it to the prestigious Olympic spectacle, T20 cricket will be the most important cricket format in times to come. The findings of this paper confirmed that comparatively test cricket is boring to tag along as it is spread over five days and one-days could be followed but on weekends, however, T20 cricket matches, which are normally played after working hours and school time in floodlights is more attractive for a larger audience. -

Ashwin Spoils Jennings Debut Ton with Three-Wicket Burst

Sports FRIDAY, DECEMBER 9, 2016 Pak has poor 1st day on Aust tour CAIRNS: Pakistan’s cricket tour of Australia got off to a shaky start yesterday when the visitors were all out for 208 on the first day of a three-day tour match against a Cricket Australia XI. Playing with a near full-strength lineup and with a pink ball in the day-night match in preparation for the first test on Dec. 15 in Brisbane - also a day-night encounter - Pakistan lost six wickets in the final session under lights. Cricket Australia XI bowler Cameron Valente claimed four wickets, including three of Pakistan’s top six. After winning the toss and electing to bat, the visitors fell to 50-3 midway through the opening session, and wickets went down steadily from there. Only veteran Younis Khan offered sustained resistance, facing 138 balls before he inside-edged a ball from Ryan Lees that swung back slightly under lights to be caught behind for 54. He was the only Pakistan batsman to reach 50. Earlier yesterday, Pakistan officials said uncapped 17-year-old left-arm spinner Mohammad Asghar would join the team as a backup for injured legspinner Yasir Shah. Shah is doubtful for the first test following a back injury which also ruled him out of the Cairns match. Asghar has taken 68 wickets in 17 first-class matches since making his debut in 2014. Shah had been pivotal to Pakistan’s suc- cess in test matches for the last two years, taking 116 wickets in only 20 tests. -

Delivering Justice: Food Delivery Cyclists in New York City

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Delivering Justice: Food Delivery Cyclists in New York City Do J. Lee The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2794 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] DELIVERING JUSTICE: FOOD DELIVERY CYCLISTS IN NEW YORK CITY by DO JUN LEE A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Psychology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 ii © 2016 DO JUN LEE All Rights Reserved iii DELIVERING JUSTICE: FOOD DELIVERY CYCLISTS IN NEW YORK CITY by DO JUN LEE This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Psychology to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Susan Saegert Date Chair of Examining Committee Richard Bodnar Date Executive Officer Michelle Fine Tarry Hum Adonia Lugo Melody Hoffmann Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv ABSTRACT Delivering Justice: Food Delivery Cyclists in New York City by Do Jun Lee Advisor: Dr. Susan Saegert In New York City (NYC), food delivery cyclists ride the streets all day and night long to provide convenient, affordable, hot food to New Yorkers. These working cyclists are often Latino or Asian male immigrants who are situated within intersectional and interlocking systems of global migration and capital flows, intense time pressures by restaurants and customers, precarious tip-based livelihoods, an e-bike ban and broken windows policing, and unsafe streets designed for drivers. -

Cricket Memorabilia Society Postal Auction Closing at Noon 10

CRICKET MEMORABILIA SOCIETY POSTAL AUCTION CLOSING AT NOON 10th JULY 2020 Conditions of Postal Sale The CMS reserves the right to refuse items which are damaged or unsuitable, or we have doubts about authenticity. Reserves can be placed on lots but must be agreed with the CMS. They should reflect realistic values/expectations and not be the “highest price” expected. The CMS will take 7% of the price realised, the vendor 93% which will normally be paid no later than 6 weeks after the auction. The CMS will undertake to advertise the memorabilia for auction on its website no later than 3 weeks prior to the closing date of the auction. Bids will only be accepted from CMS members. Postal bids must be in writing or e-mail by the closing date and time shown above. Generally, no item will be sold below 10% of the lower estimate without reference to the vendor.. Thus, an item with a £10-15 estimate can be sold for £9, but not £8, without approval. The incremental scale for the acceptance of bids is as follows: £2 increments up to £20, then £20/22/25/28/30 up to £50, then £5 increments to £100 and £10 increments above that. So, if there are two postal bids at £25 and £30, the item will go to the higher bidder at £28. Should there be two identical bids, the first received will win. Bids submitted between increments will be accepted, thus a £52 bid will not be rounded either up or down. Items will be sent to successful postal bidders the week after the auction and will be sent by the cheapest rate commensurate with the value and size of the item. -

Mental Strength Triumphs in Nail- Biting Finals Heroes: Ben Stokes (Left) and Novak Djokovic (Right) Triumphed in Tense Matches on Sunday

Mental strength triumphs in nail- biting finals Heroes: Ben Stokes (left) and Novak Djokovic (right) triumphed in tense matches on Sunday. Are mental powers in sport more exciting than physical skills? Cricketer Ben Stokes and Wimbledon champion Novak Djokovic performed under crushing pressure to seize victories on Sunday. Sunday 14 July, 7pm. At Lord’s Cricket Ground in north London, the Cricket World Cup final is — unbelievably — tied. England and New Zealand must battle it out in the first-eversuper over in the sport’s history. England batsman Ben Stokes has pulled his team back from the brink of defeat. He is exhausted, physically and emotionally, but the expectations of a nation rest on his shoulders. The pressure is on. He has just six balls to score enough runs to secure England’s first- ever cricket World Cup title. Meanwhile, on the other side of London, at Wimbledon’s Centre Court, the longest men’s tennis final in the history of the tournament goes to a fifth set tie-break. At last, Novak Djokovic has three championship points to close out this epic battle. But the crowd is cheering the name of his opponent, Roger Federer. Both men prevail under immense psychological pressure. Later, Djokovic admits the match was the most “mentally demanding” of his career. “For me, at least, it’s a constant battle within, more than what happens outside,” he said. The Serbian player is known to practise meditation and yoga to reach a state of calm. These mental tricks helped him play his best tennis for almost five hours, despite the majority of the 15,000 crowd backing Federer. -

Season 2015-16 Saw T20 Cricket Take Off Domestically with the Big Bash League Attracting Huge Crowds – Jumping Into the Top 10 for Average Crowd Size Globally

Edinburgh Cricket Club Edinburgh Cricket Club Junior Season Report 2015-2016 [Type the abstract of the document here. The abstract is typically a short summary of the contents of the document. Type the abstract of the document here. The abstract is typically a short summary of the contents of the document.] Edinburgh Cricket Club Junior Season Report 2015-2016 In the past 12 months Edinburgh Cricket Club has grown to become the second largest cricket club in Victoria. This has come about in part due to A LOOK a demographic surge in area but also, we like to think, because the Burra BACK AT is a great place for players of all ages to enjoy cricket. The number of junior SEASON teams has doubled in the past 3 years from 8 teams in season 2012-13 to 16 2015-2016 teams in 2015-16. The most exciting development this season has been the advent of our under 15 girls’ team. Women’s cricket at the Burra has been up and running for over a decade now with the woman this year taking out the WCCC North West Premiership. This season our number one priority was getting a girls’ team up and running. Slowly over the preseason numbers gathered and we just had enough players for the start of the ECA Anna Lanning Spirit competition, which runs on a Wednesday evening. Despite their ages ranging from 8 to 13, the girls quickly bonded into a team and before long were playing some great cricket. Word spread and numbers grew over the season so that next season we hope to have 2 teams. -

T20 Rules Cheat Sheet

T20 Rules Cheat Sheet ON CALL UMPIRE CONTACTS POWER PLAY Ramesh Ailaveni 480-252-0243 Overs in Innings Power Play Overs Unmil Patel 952-393-6992 19-20 6 Abhijeet Surve 651-983-5502 15-18 5 Tulsie 952-250-4178 12-14 4 SriKrishnan 612-345-1779 9-11 3 Nitin Reddy Pasula 214-226-7768 5-8 2 Basic Rules 1. During power play only 2 fielders are permitted to be outside 30 yards, fielders in catching position not required. 2. During non power play no more than 5 fielders can be outside 30 yards. 3. A batsmen can be out on free hit, if he is run out or handled the ball or hit the ball twice or obstructs the field. 4. Apply duck-worth for any interruption that requires over reductions. 5. A minimum of 5 overs constitutes a match. 6. Play can be extended beyond scheduled cut off , if there is enough light just to complete minimum overs to get a result. 7. Beamer 1. A delivery which is other than a slow paced one and passes on the full above waist height or 2. A delivery which is slow paced and passes on the full above shoulder. 3. First instance of beamer is called no ball with warning. Second instance any time in the innings is called no ball and bowler can not bowl further in that innings. 8. Bouncer - above shoulder height but not above the head. Bouncer above head is called wide. 1. If bowled in same over 1. first one allowed, second one no ball with first warning, third one no ball with final warning, fourth one no ball and bowler can not bowl further in that innings. -

Name – Nitin Kumar Class – 12Th 'B' Roll No. – 9752*** Teacher

ON Name – Nitin Kumar Class – 12th ‘B’ Roll No. – 9752*** Teacher – Rajender Sir http://www.facebook.com/nitinkumarnik Govt. Boys Sr. Sec. School No. 3 INTRODUCTION Cricket is a bat-and-ball game played between two teams of 11 players on a field, at the centre of which is a rectangular 22-yard long pitch. One team bats, trying to score as many runs as possible while the other team bowls and fields, trying to dismiss the batsmen and thus limit the runs scored by the batting team. A run is scored by the striking batsman hitting the ball with his bat, running to the opposite end of the pitch and touching the crease there without being dismissed. The teams switch between batting and fielding at the end of an innings. In professional cricket the length of a game ranges from 20 overs of six bowling deliveries per side to Test cricket played over five days. The Laws of Cricket are maintained by the International Cricket Council (ICC) and the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) with additional Standard Playing Conditions for Test matches and One Day Internationals. Cricket was first played in southern England in the 16th century. By the end of the 18th century, it had developed into the national sport of England. The expansion of the British Empire led to cricket being played overseas and by the mid-19th century the first international matches were being held. The ICC, the game's governing body, has 10 full members. The game is most popular in Australasia, England, the Indian subcontinent, the West Indies and Southern Africa. -

FACT SHEET - DAY 1 LIBRARY Beginning with the Inaugural Test Match in March 1877, 107 Tests Have Been Staged at the MCG

AUSTRALIA V. WEST INDIES DECEMBER 26, 2015 BOXING DAY TEST FACT SHEET - DAY 1 LIBRARY Beginning with the inaugural Test match in March 1877, 107 Tests have been staged at the MCG. One Test, in 1970/71, was abandoned without a ball bowled and is not counted in the records. Fourteen of the matches have involved West Indies, Australia winning 10 of those contests, West Indies three, with the other drawn. The other sides to play Tests at the MCG are England (55), India (12), South Africa (12), Pakistan (9), New Zealand (3) and Sri Lanka (2). Only Lord's Cricket Ground (130) has hosted more Test matches than the MCG. As Lord's currently has two Test matches per summer (it hosted three in 2010), it will extend its lead as the MCG has not hosted two Test matches in the same season since 1981/82. Of the 114 Tests between Australia and West Indies to date, Australia has won 57, West Indies 32, one has been tied and the remaining 24 drawn. The current Test is Australia's 785th and West Indies’ 512th. Of its 784 Tests to date, Australia has won 363 (46.30 per cent), lost 205 (26.14 per cent) and tied two. The remaining 202 have been drawn. The fact sheets for today's game will review the inaugural five-Test series between the two countries, the first match beginning at Adelaide Oval on 18 December 1930, 85 years ago, almost to the day. A summary of each match will appear during the course of this game, beginning with the First Test on today's sheet, followed by each of the remaining games in sequence on the sheets for subsequent days.