George Foster Practicing Medical Anthropology Award

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

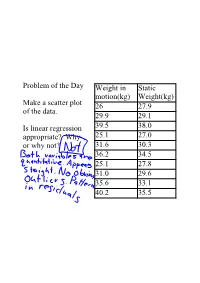

Problem of the Day Make a Scatter Plot of the Data. Is Linear Regression

Problem of the Day Weight in Static motion(kg) Weight(kg) Make a scatter plot 26 27.9 of the data. 29.9 29.1 Is linear regression 39.5 38.0 appropriate? Why 25.1 27.0 or why not? 31.6 30.3 36.2 34.5 25.1 27.8 31.0 29.6 35.6 33.1 40.2 35.5 Salary(in Problem of the Day Player Year millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 Is it appropriate to use George Foster 1982 2.0 linear regression Kirby Puckett 1990 3.0 to predict salary Jose Canseco 1991 4.7 from year? Roger Clemens 1996 5.3 Why or why not? Ken Griffey, Jr 1997 8.5 Albert Belle 1997 11.0 Pedro Martinez 1998 12.5 Mike Piazza 1999 12.5 Mo Vaughn 1999 13.3 Kevin Brown 1999 15.0 Carlos Delgado 2001 17.0 Alex Rodriguez 2001 22.0 Manny Ramirez 2004 22.5 Alex Rodriguez 2005 26.0 Chapter 10 ReExpressing Data: Get It Straight! Linear Regressioneasiest of methods, how can we make our data linear in appearance Can we reexpress data? Change functions or add a function? Can we think about data differently? What is the meaning of the yunits? Why do we need to reexpress? Methods to deal with data that we have learned 1. 2. Goal 1 making data symmetric Goal 2 make spreads more alike(centers are not necessarily alike), less spread out Goal 3(most used) make data appear more linear Goal 4(similar to Goal 3) make the data in a scatter plot more spread out Ladder of Powers(pg 227) Straightening is good, but limited multimodal data cannot be "straightened" multiple models is really the only way to deal with this data Things to Remember we want linear regression because it is easiest (curves are possible, but beyond the scope of our class) don't choose a model based on r or R2 don't go too far from the Ladder of Powers negative values or multimodal data are difficult to reexpress Salary(in Player Year Find an appropriate millions) Nolan Ryan 1980 1.0 linear model for the George Foster 1982 2.0 data. -

Major Leagues Are Enjoying Great Wealth of Star

MAJOR LEAGUES ARE ENJOYING GREAT WEALTH OF STAR FIRST SACKERS : i f !( Major League Leaders at First Base l .422; Hornsby Hit .397 in the National REMARKABLE YEAR ^ AMERICAN. Ken Williams of Browns Is NATIONAL. Daubert and Are BATTlMi. Still Best in Hitting BATTING. Pipp Play-' PUy«,-. club. (1. AB. R.11. HB SB.PC. Player. Club. G. AB. R. H. I1R. SB. PC. Slsler. 8*. 1 182 SCO 124 233 7 47 .422 iit<*- Greatest Game of Cobb. r>et 726 493 89 192 4 111 .389 Home Huns. 105 372 52 !4rt 7 7 .376 Sneaker, Clev. 124 421 8.1 ir,« 11 8 .375 liar foot. St. L. 40 5i if 12 0 0 .375 I'll 11 Lives. JlHTneyt Det 71184 33 67 0 2 .364 Russell, Pitts.. 48 175 43 05 12 .4 .371 l.-llmunn, D«t. 118 474! #2 163 21 8 .338 Konseca, Cln. (14 220 39 79 2 3 .859 Hugh, N. Y 34 84 14 29 0 0 .347.! George Sisler of the Browne is the Stengel, N. V.. 77 226 42 80 6 5 .354 Woo<lati, 43 108 17 37 0 0 H43 121 445 90 157 13 6 .35.4 N. Y Ill 3?9 42 121 1 It .337 leading hitter of the American League 133 544 100 191 3 20 .351 IStfcant. .110 418 52 146 11 5 .349 \ an Glider, St. I.. 4<"» 63 15 28 2 0 .337 with a mark of .422. George has scored SISLER STANDS A I TOP 'i'obln, fit J 188 7.71 114 182 11 A .336 Y 71 190 34 66 1 1 .347 Ftagsloart, Det 87 8! 18 27 8 0 .833 the most runs. -

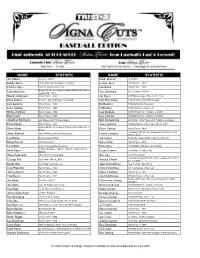

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

Sustainable Livelihood Approach: a Critical Analysis of Theory and Practice

Sustainable Livelihood Approach: A critical analysis of theory and practice. Stephen Morse, Nora McNamara and Moses Acholo Geographical Paper No. 189 Sustainable Livelihood Approach: A critical analysis of theory and practice. Geographical Paper No. 189 Stephen Morse Department of Geography, University of Reading, UK [email protected] Nora McNamara and Moses Acholo Diocesan Development Services (DDS), Idah, Kogi State, Nigeria November 2009 Series Editor: A.M.Mannion [email protected] 1 Contents Section Page number 1. Introduction 4 2. The SLA context; two villages in Nigeria. 16 3. The SLA space 18 4. Practice of SLA 21 5. Human capital: the households 23 6. Natural capital: land and farming 29 7. Natural capital: Trees 37 8. Social capital: Networks 40 9. Physical capital: assets for income generation 44 10. Financial capital: household budgets 52 11. Vulnerability context 56 12. Did SLA succeed? 58 13. Some conclusions 63 14. Acknowledgements 64 15. References 64 2 Abstract Sustainable Livelihood Analysis (SLA) has since the 1990s become the dominant approach to the implementation of development interventions by a number of major international agencies. It is defined in terms of the ability of a social unit to enhance its assets and capabilities in the face of shocks and stresses over time. SLA first seeks to identify the important assets in livelihood, their trends over time and space as well as the nature and impacts of shocks and stresses (environmental, economic and social) upon these assets. Following this, and after taking cognisance of the wider context (e.g. political, legal, economic, institutions, infrastructure etc.), interventions are designed to address any vulnerability of enhance livelihoods perhaps by diversification of income streams. -

Anthropology of Food and Nutrition Spring 2017 Syllabus Provisional Update

Nutrition 330: Anthropology of Food and Nutrition Spring 2017 Syllabus Provisional Update Class Meetings: Wednesday, 3:15-6:15 pm in Jaharis 155 Instructor: Ellen Messer, PhD (http://www.nutrition.tufts.edu/faculty/messer-ellen) Contact: [email protected] Office Hours: TBA Tufts Graduate Credit: 1 cr. Prerequisites: Some social science background Course Description: This course provides an advanced introduction to anthropological theory and methods designed for food and nutrition science and policy graduate students. Section 1 covers anthropology's four-field modes of inquiry, cross-cutting theoretical approaches and thematic interest groups, their respective institutions and intellectual concerns. Section 2 demonstrates applications of these concepts and methods to cutting-edge food and nutrition issues. Assignments and activities incorporate background readings, related discussions, and short writing assignments, plus an anthropological literature review on a focused food and nutrition project, relevant to their particular interests. The course overall encourages critical thinking and scientific assessment of anthropology's evidence base, analytical tools, logic, and meaning-making, in the context of contributions to multi-disciplinary research and policy teams. Weekly 3-hour sessions feature an introductory overview lecture, student-facilitated discussion of readings, and professor-moderated debate or exercise illustrating that week's themes. Throughout the term, participants keep a written reading log (critical response diary), to be handed in week 3 and 6. In lieu of a mid-term exam, there are two 2-page graded written essay assignments, due weeks 4 and 8. The term-long food-and nutrition proposal- writing project will explore anthropological literature on a focused food and nutrition question, with an outline due week 9, and a short literature review and annotated bibliography due week 12. -

2020 Topps Archives Signatures Baseball Checklist

2020 Topps Archives Signatures Retired Baseball Player List - 110 Players Al Oliver David Cone Jim Rice Mike Schmidt Tim Lincecum Alex Rodriguez David Justice Jim Thome Mo Vaughn Tim Raines Andre Dawson David Ortiz Joe Mauer Moises Alou Tino Martinez Andres Galaragga David Wright Joe Pepitone Nolan Ryan Todd Helton Andruw Jones Dennis Eckersley John Smoltz Nomar Garciaparra Tom Glavine Andy Pettitte Dennis Martinez Johnny Bench Ozzie Smith Tony Perez Barry Larkin Don Mattingly Johnny Damon Randy Johnson Vern Law Barry Zito Dwight Gooden Jorge Posada Reggie Jackson Vladimir Guerrero Bartolo Colon Edgar Martinez Jose Canseco Rey Ordonez Wade Boggs Benito Santiago Eric Chavez Juan Gonzalez Rickey Henderson Will Clark Bernie Carbo Eric Davis Juan Marichal Roberto Alomar Bernie Williams Frank Thomas Ken Griffey Jr. Robin Yount Bert Blyleven Fred McGriff Kerry Wood Rod Carew Bob Gibson George Foster Lou Brock Roger Clemens Bronson Arroyo Gorman Thomas Luis Gonzalez Rollie Fingers Cal Ripken Jr. Hank Aaron Luis Tiant Rondell White Carl Yazstremski Hideki Matsui Magglio Ordonez Ruben Sierra Carlton Fisk Ichiro Manny Sanguillen Ryan Howard CC Sabathia Ivan Rodriguez Mariano Rivera Ryne Sandberg Cecil Fielder Jason Varitek Mark Grace Sandy Alomar Jr. Chipper Jones Jay Buhner Mark McGwire Sandy Koufax Cliff Floyd Jeff Bagwell Mark Teixeira Sean Casey Dale Murphy Jeff Cirillo Maury Willis Shawn Green Darryl Strawberry Jerry Remy Miguel Tejeda Steve Carlton Dave Stewart Jim Abbott Mike Mussina Steve Rogers 2020 Topps Archives Signatures Baseball Player List - 110 Players. -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

Baseball All-Time Stars Rosters

BASEBALL ALL-TIME STARS ROSTERS (Boston-Milwaukee) ATLANTA Year Avg. HR CHICAGO Year Avg. HR CINCINNATI Year Avg. HR Hank Aaron 1959 .355 39 Ernie Banks 1958 .313 47 Ed Bailey 1956 .300 28 Joe Adcock 1956 .291 38 Phil Cavarretta 1945 .355 6 Johnny Bench 1970 .293 45 Felipe Alou 1966 .327 31 Kiki Cuyler 1930 .355 13 Dave Concepcion 1978 .301 6 Dave Bancroft 1925 .319 2 Jody Davis 1983 .271 24 Eric Davis 1987 .293 37 Wally Berger 1930 .310 38 Frank Demaree 1936 .350 16 Adam Dunn 2004 .266 46 Jeff Blauser 1997 .308 17 Shawon Dunston 1995 .296 14 George Foster 1977 .320 52 Rico Carty 1970 .366 25 Johnny Evers 1912 .341 1 Ken Griffey, Sr. 1976 .336 6 Hugh Duffy 1894 .440 18 Mark Grace 1995 .326 16 Ted Kluszewski 1954 .326 49 Darrell Evans 1973 .281 41 Gabby Hartnett 1930 .339 37 Barry Larkin 1996 .298 33 Rafael Furcal 2003 .292 15 Billy Herman 1936 .334 5 Ernie Lombardi 1938 .342 19 Ralph Garr 1974 .353 11 Johnny Kling 1903 .297 3 Lee May 1969 .278 38 Andruw Jones 2005 .263 51 Derrek Lee 2005 .335 46 Frank McCormick 1939 .332 18 Chipper Jones 1999 .319 45 Aramis Ramirez 2004 .318 36 Joe Morgan 1976 .320 27 Javier Lopez 2003 .328 43 Ryne Sandberg 1990 .306 40 Tony Perez 1970 .317 40 Eddie Mathews 1959 .306 46 Ron Santo 1964 .313 30 Brandon Phillips 2007 .288 30 Brian McCann 2006 .333 24 Hank Sauer 1954 .288 41 Vada Pinson 1963 .313 22 Fred McGriff 1994 .318 34 Sammy Sosa 2001 .328 64 Frank Robinson 1962 .342 39 Felix Millan 1970 .310 2 Riggs Stephenson 1929 .362 17 Pete Rose 1969 .348 16 Dale Murphy 1987 .295 44 Billy Williams 1970 .322 42 -

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings January 30, 2019

Cincinnati Reds Press Clippings January 30, 2019 THIS DAY IN REDS HISTORY 1919-The Reds hire Pat Moran as manager, replacing Christy Mathewson, when no word is received from him while his is in France with the U.S. Army. Moran would manage the Reds until 1923, collecting a 425-329 record 1978-Former Reds executive, Larry MacPhail, is elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum 1997-The Reds sign Deion Sanders to a free agent contract, for the second time ESPN.COM Busy Reds in on Realmuto, but would he make them a contender? Jan. 29, 2019 Buster Olney ESPN Senior Writer The last time the Cincinnati Reds won a postseason series, Joey Votto was 12 years old, Bret Boone was the team's second baseman and the organization had only recently drafted his kid brother, a third baseman out of the University of Southern California named Aaron Boone. Since the Reds swept the Dodgers in a Division Series in 1995, they have built more statues than they have playoff wins. In recent years, a Dodger said he was sick of Kirk Gibson -- not because of anything Gibson had done, but because the team had felt the need to roll out the highlight of Gibson's epic '88 World Series home run, in lieu of subsequent championship success. Similarly, most of the biggest stars in the Reds organization continue to be Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan, Pete Rose and Tony Perez, as well as announcer Marty Brennaman, who recently announced he will retire after the upcoming season. -

ON HAND. for the Disabled Is Headquarters for Your Artcarved College Rings Is Your Campos Bookstore

Wednesday • March* 24, 1982 • The Lumberjack • page 7 S p o rts National League baseball predictions Expos, Dodgers to fight for pennant JONATHAN STERN away a number of older championship-seasor, 2. ATLANTA - The Braves have come of Spoft» Analysis players for promising minoMeaguers. Right age. Third baseman Bob Horner leads a fielder Dave Parker and first baseman Jason devastating hitting team along with first The following is the first of two parts of thisThompson both want to be traded but Pitt baseman Chris Chambliss and left fielder Dale year's major league baseball predictions. sburgh can't get enough for them. Parker and Murphy. Catcher Bruce Benedict and center It’s a close race in the National League West Thompson are expected to stick around fielder Claudell Washington provide critical hit but the experienced Los Angeles Dodgers willanother year. League batting champion Bill ting. A sound infield led by second baseman hold off the youthful Atlanta Braves and the ag Madlock returns at third base and the fleet Glenn Hubbard will help pitchers Phil Niekro, ing Cincinnati Reds. Omar Moreno is back in center field. Catcher Rick Mahler, Gene Garber and Rick Camp. The Montreal Expos will have an easy time in Tony Pena, second baseman Johnnie Ray and Watch out! the NL East with only the inexperienced St. shortshop Dale Berra head the Pirates' youth 3. CINCINNATI - The Reds' entire outfield Louis Cardinals nipping at them. Expect Mon movement. has been replaced Ihrough free-agency" and treal to down Los Angeles and play in its first 5. NEW YORK - Errors, errors, errors .. -

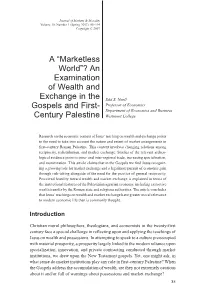

An Examination of Wealth and Exchange in the Gospels and First

Journal of Markets & Morality Volume 10, Number 1 (Spring 2007): 85–114 Copyright © 2007 A “Marketless World”? An Examination of Wealth and Exchange in the Edd S. Noell Gospels and First- Professor of Economics Department of Economics and Business Century Palestine Westmont College Research on the economic context of Jesus’ teaching on wealth and exchange points to the need to take into account the nature and extent of market arrangements in first-century Roman Palestine. This context involves changing relations among reciprocity, redistribution, and market exchange. Studies of the relevant archeo- logical evidence point to intra- and inter-regional trade, increasing specialization, and monetization. This article claims that in the Gospels we find Jesus recogniz- ing a growing role for market exchange and a legitimate pursuit of economic gain through risk-taking alongside of the need for the practice of general reciprocity. Perceived hostility toward wealth and market exchange is explained in terms of the institutional features of the Palestinian agrarian economy, including extractive wealth transfer by the Roman state and religious authorities. The article concludes that Jesus’ teachings on wealth and market exchange have greater moral relevance to modern economic life than is commonly thought. Introduction Christian moral philosophers, theologians, and economists in the twenty-first century face a special challenge in reflecting upon and applying the teachings of Jesus on wealth and possessions. In attempting to speak to a culture preoccupied with material prosperity, a prosperity largely linked to the modern reliance upon specialization, innovation, and private contracting conducted through market institutions, we draw upon the New Testament gospels. -

Cumulativeindex

Cumulative Index Edited by Mary Ellin D'Agostino with Robert V. Kemper (volumes 1-40) Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers Number 78, 1995 The Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers, Number 79 C 1995 Kroeber Anthropological Society Mary Ellin D'Agostino, Editor Membership: Subscription is by membership in the Kroeber Anthropological Society. Dues for student members are $18.00, for regular members (including institutions) are $20.00, and all foreign subscribers $24.00 in US currency. Back issues ofthe Papers are available for $12.00 per issue plus $2.00 shipping and handling in the United States, Mexico, and Canada; foreign orders should add $4.00 shipping and handling. Prices subject to change without notice. Informationfor authors: The Kroeber Anthropological Society publishes articles in the general field of anthropology. In addition to articles oftheoretical interest, the Papers welcome descriptive studies putting factual information on record and historical documents ofanthropological interest. The society welcomes student research papers ofhigh quality. Submitted papers should not exceed 30 typewritten, double spaced pages and conform to the style used by the American Anthropological Association. Two paper copies and one computer copy ofthe manuscript should be submitted. Computer copies should be on 3V/2" diskette in formatted for either Mac or DOS, text should be in WordPerfect, Microsoft Word, or plain (ASCII) text format. Email submissions are acceptable, but should be followed up with regular mail. All inquiries should be sent to: Kroeber Anthropological Society Department ofAnthropology University of Califomia Berkeley, CA 94720-3710 email: kasgqal.berkeley.edu Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers, No. 78, 1995 Cumulative Index Edited by Mary Ellin D 'Agostino with Robert V Kemper (volumes 1-40) First published in 1950, the Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers is the oldest student run, student edited anthropologyjournal in the United States.