1 Frederick Stearns, Leopoldo Franciolini, and the Making of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Anthropological Perspective on Eastern and Western Folk Music

An Anthropological Perspective on Eastern and Western Folk Music Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Gurczak, Adam Stanley Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 21:02:58 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/625002 AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE ON EASTERN AND WESTERN FOLK MUSIC By ADAM STANLEY GURCZAK ____________________ A Thesis Submitted to The Honors College In Partial Fulfillment of the Bachelors Degree With Honors in Music Performance THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA MAY 2017 Approved by: _________________________ Dr. Philip Alejo Department of Music EASTERN AND WESTERN FOLK MUSIC 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 2 ARTIST’S STATEMENT 2 INTRODUCTION 3 ARGENTINE TANGO 4 PRE-TANGO HISTORY: RISE OF THE GAUCHOS 5 A BORDELLO UPBRINGING 5 THE ROOTS AND RHYTHMS OF TANGO 8 A WORLDWIDE SENSATION 9 THE FOREFATHERS OF TANGO 11 CHINESE TRADITIONAL MUSIC 13 THE PHILOSOPHY OF MUSIC 14 INSTRUMENTS OF THE EARTH 16 THE SOUND OF SCHOLARS 18 KOREAN GUGAK 21 GUGAK: A NATIONAL IDENTITY 22 SHAMANS, SINAWI, AND SANJO 24 NOBLE COURTS AND FARMYARDS 28 AMERICAN BLUEGRASS 30 GRASSROOTS, BLUEGRASS, AND BLUES 30 THE POLYNATION OF BLUEGRASS 33 CONCLUSION 36 BIBLIOGRAPHY 37 EASTERN AND WESTERN FOLK MUSIC 2 ABSTRACT The birth of folk music has always depended on the social, political, and cultural conditions of a particular country and its people. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

Roland Axis-1 Manual

Roland Axis-1 Manual Keyboard Controller. AX-1 Electronic Keyboard pdf manual download. Electronic Keyboard Roland AXIS-1 Owner's Manual. Midi keaboard (36 pages). Vintage-Roland-AXIS-1-Keytar- Keyboard-MIDI-Controller Copy of the original Owner's manual. Guaranteed NO DOA – Bid With Confidence. Flat shipping. BT-1 Bar Trigger Pad CDX-1 DiscLab FR-1 V-Accordion GLC-1 Lab Conferencing System · GR-1 Guitar Synthesizer. 3 posts • Page 1 of 1 The machine appears to move fine in the XY axis, whether using the buttons on the machine or via the software. The manual Z axis down control will not work without the plastic safety cover being. if this is unusable. A-110 Owner's Manual ADA-8024 Owner's Manual · AF-70 Owner's Manual · AP-700 Owner's Manual AXIS-1 Owner's Manual. picked up a Roland HS-10 (Alpha Juno 1) for a good price. All. Manual - Get a copy of the Alpha Juno-1 manual here in PDF format. SysEx Basics - Helpful. Roland Axis-1 Manual Read/Download Roland AXIS-1 Service Notes (10 Pages). Roland AX-Synth Owners Manual (46 Pages). Roland BA-55 Owners Manual (176 Pages). Roland BC-13 Owners. 1 List of keytars, 2 Custom/rare keytars. 2.1 Rare keytar products 1795, Orphica, acoustic piano, –, a portable miniature piano in horizontal harp form. 1985, Roland AXIS, controller, MIDI Dynacord Rhythm Stick MIDI - operating manual. The Global website of Roland Corporation, a leading manufacturer and distributor The JD-Xi Dance Collection Volume 1 includes 16 new Programs using. -

FW May-June 03.Qxd

IRISH COMICS • KLEZMER • NEW CHILDREN’S COLUMN FREE Volume 3 Number 5 September-October 2003 THE BI-MONTHLY NEWSPAPER ABOUT THE HAPPENINGS IN & AROUND THE GREATER LOS ANGELES FOLK COMMUNITY Tradition“Don’t you know that Folk Music is Disguisedillegal in Los Angeles?” — WARREN C ASEY of the Wicked Tinkers THE FOLK ART OF MASKS BY BROOKE ALBERTS hy do people all over the world end of the mourning period pro- make masks? Poke two eye-holes vided a cut-off for excessive sor- in a piece of paper, hold it up to row and allowed for the resump- your face, and let your voice tion of daily life. growl, “Who wants to know?” The small mask near the cen- The mask is already working its ter at the top of the wall is appar- W transformation, taking you out of ently a rendition of a Javanese yourself, whether assisting you in channeling this Wayang Topeng theater mask. It “other voice,” granting you a new persona to dram- portrays Panji, one of the most atize, or merely disguising you. In any case, the act famous characters in the dance of masking brings the participants and the audience theater of Java. The Panji story is told in a five Alban in Oaxaca. It represents Murcielago, a god (who are indeed the other participants) into an arena part dance cycle that takes Prince Panji through of night and death, also known as the bat god. where all concerned are willing to join in the mys- innocence and adolescence up through old age. -

Musical Journey Study Guide for Teachers

Lorinda Jones ! Education Support Materials ! Teacher/Student Study Guide ! “A Musical Journey of Kentucky” ! Program Goal: ! Students will identify how immigration, lifestyle, and significant events in history, developed into the folk music of Kentucky and the Appalachian region of the United States specifically through the evolution of instruments and song. ! ! Program Description: ! An energetic performance on the state instrument of Kentucky, the mountain dulcimer, captures the focus of the students from the beginning and continues through to the end with songs, stories, and instruments that delight the audience. Students are challenged to think about the origin and roots of the mountain music that is important to Kentucky’s heritage. Taking a trip through time, students begin to understand that music has evolved due to immigration and significant historical events and periods of history. The unique instruments that capture the student’s attention may include: gourd banjo, modern banjo, fiddle, harp, Irish whistle, autoharp, psaltery, Scheitholt, guitar, and mountain dulcimers. Song selections are age appropriate and include sing alongs for audience participation. A powerpoint slideshow can accompany the performance (if slide and projector available) and enhances the program with additional historical information and song lyrics. ! ! ! ! ! Art Form: Music ! Students are exposed to a variety of folk instruments, primarily stringed, as well as songs and musical terms. ! Students are challenged to make connections between history, culture, immigration and the effect on folk music. ! Students are given the opportunity to see a number of rare instruments performed in a concert-like “live performance” setting, rather than through pictures or video. ! ! Curriculum Standards ! This program is designed to meet the core content standards in the area of arts and humanities, specifically, American folk music, historical significance and origin. -

Cognitive Consonance

CHRISTOPHER TRAPANI COGNITIVE CONSONANCE Two studies for two plucked-string soloists, ensemble, and electronics (2010) Cognitive Consonance (2010) I. Disorientation (qanûn solo) Interlude II. Westering (hexaphonic electric guitar solo) —————— Duration: ca. 23 minutes Score in C Instrumentation: Qanûn Solo Hexaphonic Electric Guitar Solo Alto Flute / Flute (only in II. Westering) Clarinet in B flat / Bass Clarinet in B flat (only in II. Westering) Mandolin / Just Intonation Autoharp in G Harp Guitar (nylon strings, only in I. Disorientation) Percussion (1 player): Crotales, Glockenspiel, Vibraphone, Marimba, Zarb, Bendir, Snare Drum, 2 suspended Cymbals, 5 tuned gongs (G#2, B2, D3, F3, C#4) Violin Cello Contrabass (with low C string or 5th string retuned to C) —————— Cognitive Consonance was written in conjunction with the Cursus 2 at IRCAM, and premiered during the Agora festival on 9 June 2010 at the CENTQUATRE in Paris, with Julien Jalâl Eddine Weiss on qanûn, Christelle Séry on hexaphonic electric guitar, and the Ensemble L’Itinéraire conducted by Mark Foster. The electronics were realized at IRCAM by the composer, under the guidance of Eric Daubresse. Performance Notes: 1. Disorientation was written specifically for the qanûn player Julien Weiss, using his system of intonation — with 15 microtonal possibilities between C flat and C sharp — and notation, with the accidentals outlined in figure 1. 2. The hexaphonic electric guitar is a custom instrument, fitted with a hexaphonic pickup (such as the Roland GK-3) capable of sending out a separate signal for each string. These six signals must be sent to the patch, so a converting device such as the RMC fanout box may also be needed. -

Timothy Seaman's Music Lessons

Timothy Seaman Compelling Instrumentals Fifteen distinctive and original instrumental CD recordings celebrating Virginia’s Parks, nature, & history, Celtic melodies & Christmas joy --- over 13134444,000,000 copies madmade,e, plus countless downloads &&& playsplaysplays TTTTiiiimmmmooootttthhhhyyyy SSSSeeeeaaaammmmaaaannnn’’’’’’ssss MMuuuussssiiiicccc LLLLeeeessssssssoooonnnnssss Hammered Dulcimer (A(A(All(A ll levels); Beginner to Advanced Beginner levels: FluteFlute,, PennywPennywhistlehistlehistle,, Folk GuitarGuitar,, Mountain DulcimerDulcimer,, UkuleleUkulele,,,, PsalteryPsaltery,, Autoharp LocationLocationssss:: Either Providence Classical School 1)1)1) Musicality --------- Discover how to be expressive music studio in Jamestown, Virginia, or online via with music in its phrasing and voicing --- to Skype TM or FaceTimeFaceTime. make your instrument sing! 2)2)2) Scale and chord theory --------- Learn the basics Lessons on weekdays : any open time from 3 pm to of how music is built and how a melody, 8 pm Eastern Time. (More flexible in summer.) chords, and rhythm relate to that! FFFlexibFlexiblexiblele schedulingscheduling:: lessons can be a week apart, or 3)3)3) Arrangement, improvisation, and two weeks, or more. composition --------- I want to show you how Personalized Plan : tailored according to the goals easy and rewarding it really is to create your own music! and needs of the student. Lesson length may be scheduled for a half hour, an hour or even two hours Rental dulcimers : I have relatively small, good when distance or other factors are a consideration. quality hammered dulcimers for rent if needed. First Lesson Bonus Time: at least 15 minutes extra I welcome phone calls or ee----mailmail if you’d like to at the first lesson to make sure plenty of material is consider a lesson or more on hammered dulcimer, covered. -

(EN) SYNONYMS, ALTERNATIVE TR Percussion Bells Abanangbweli

FAMILY (EN) GROUP (EN) KEYWORD (EN) SYNONYMS, ALTERNATIVE TR Percussion Bells Abanangbweli Wind Accordions Accordion Strings Zithers Accord‐zither Percussion Drums Adufe Strings Musical bows Adungu Strings Zithers Aeolian harp Keyboard Organs Aeolian organ Wind Others Aerophone Percussion Bells Agogo Ogebe ; Ugebe Percussion Drums Agual Agwal Wind Trumpets Agwara Wind Oboes Alboka Albogon ; Albogue Wind Oboes Algaita Wind Flutes Algoja Algoza Wind Trumpets Alphorn Alpenhorn Wind Saxhorns Althorn Wind Saxhorns Alto bugle Wind Clarinets Alto clarinet Wind Oboes Alto crumhorn Wind Bassoons Alto dulcian Wind Bassoons Alto fagotto Wind Flugelhorns Alto flugelhorn Tenor horn Wind Flutes Alto flute Wind Saxhorns Alto horn Wind Bugles Alto keyed bugle Wind Ophicleides Alto ophicleide Wind Oboes Alto rothophone Wind Saxhorns Alto saxhorn Wind Saxophones Alto saxophone Wind Tubas Alto saxotromba Wind Oboes Alto shawm Wind Trombones Alto trombone Wind Trumpets Amakondere Percussion Bells Ambassa Wind Flutes Anata Tarca ; Tarka ; Taruma ; Turum Strings Lutes Angel lute Angelica Percussion Rattles Angklung Mechanical Mechanical Antiphonel Wind Saxhorns Antoniophone Percussion Metallophones / Steeldrums Anvil Percussion Rattles Anzona Percussion Bells Aporo Strings Zithers Appalchian dulcimer Strings Citterns Arch harp‐lute Strings Harps Arched harp Strings Citterns Archcittern Strings Lutes Archlute Strings Harps Ardin Wind Clarinets Arghul Argul ; Arghoul Strings Zithers Armandine Strings Zithers Arpanetta Strings Violoncellos Arpeggione Keyboard -

Medium of Performance Thesaurus for Music

A clarinet (soprano) albogue tubes in a frame. USE clarinet BT double reed instrument UF kechruk a-jaeng alghōzā BT xylophone USE ajaeng USE algōjā anklung (rattle) accordeon alg̲hozah USE angklung (rattle) USE accordion USE algōjā antara accordion algōjā USE panpipes UF accordeon A pair of end-blown flutes played simultaneously, anzad garmon widespread in the Indian subcontinent. USE imzad piano accordion UF alghōzā anzhad BT free reed instrument alg̲hozah USE imzad NT button-key accordion algōzā Appalachian dulcimer lõõtspill bīnõn UF American dulcimer accordion band do nally Appalachian mountain dulcimer An ensemble consisting of two or more accordions, jorhi dulcimer, American with or without percussion and other instruments. jorī dulcimer, Appalachian UF accordion orchestra ngoze dulcimer, Kentucky BT instrumental ensemble pāvā dulcimer, lap accordion orchestra pāwā dulcimer, mountain USE accordion band satāra dulcimer, plucked acoustic bass guitar BT duct flute Kentucky dulcimer UF bass guitar, acoustic algōzā mountain dulcimer folk bass guitar USE algōjā lap dulcimer BT guitar Almglocke plucked dulcimer acoustic guitar USE cowbell BT plucked string instrument USE guitar alpenhorn zither acoustic guitar, electric USE alphorn Appalachian mountain dulcimer USE electric guitar alphorn USE Appalachian dulcimer actor UF alpenhorn arame, viola da An actor in a non-singing role who is explicitly alpine horn USE viola d'arame required for the performance of a musical BT natural horn composition that is not in a traditionally dramatic arará form. alpine horn A drum constructed by the Arará people of Cuba. BT performer USE alphorn BT drum adufo alto (singer) arched-top guitar USE tambourine USE alto voice USE guitar aenas alto clarinet archicembalo An alto member of the clarinet family that is USE arcicembalo USE launeddas associated with Western art music and is normally aeolian harp pitched in E♭. -

Instrument Families: String All String Instruments Have Something in Common: They All Make Sound When Their Strings Wiggle/Vibrate

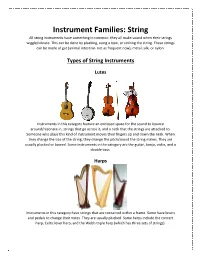

Instrument Families: String All string instruments have something in common: they all make sound when their strings wiggle/vibrate. This can be done by plucking, using a bow, or striking the string. These strings can be made of gut (animal intestine- not as frequent now), metal, silk, or nylon. Types of String Instruments Lutes Instruments in this category feature an enclosed space for the sound to bounce around/resonate in, strings that go across it, and a neck that the strings are attached to. Someone who plays this kind of instrument moves their fingers up and down the neck. When they change the size of the string, they change the pitch/sound the string makes. They are usually plucked or bowed. Some instruments in the category are the guitar, banjo, violin, and a double bass. Harps Instruments in this category have strings that are contained within a frame. Some have levers and pedals to change their notes. They are usually plucked. Some harps include the concert harp, Celtic lever harp, and the Welsh triple harp (which has three sets of strings). Zithers Instruments in this category typically have many strings stretched over a flat sounding board. They are laid flat and are either played by strumming, with a pick, a bow, have keys (like a piano), or in some cases “hammers.” Some instruments in this category are the autoharp, hammered dulcimer, or bowed psaltery. Activities for Your Child How is a Violin Made? Below are two videos from the show How It’s Made: one about making violins and the other is about making electric violins. -

Autoharp Notes

Promoting the Autoharp Spring 2014 across the UK Autoharp Notes President’s Perspectives Hello Everyone, Welcome to a new autoharping year wherever you are, although by the time you read this we’ll be a good two months and more into 2014. As usual there are plenty of events occurring this year – both those organised by UKA, and those other regular dates, quite apart from whatever else you may be doing locally and privately to continue your autoharp journey. I’m hoping to make every UKA event this year, as well as attending Inside this issue: Sore Fingers Easter Week. And for a very tasty starter we have Mike President’s Perspectives and Rachel Fenton’s Day in Tewkesbury on Saturday 22nd March by Neil Gillard 1 Page 1 Editor’s RamblingsAutoharp Notes to look forward to, where the tutors include Mike himself, Heather by Judy Spindler 2 An ‘Electric Harp’ Indeed Farrell-Roberts, Guy Padfield and our very own Mountain Laurel prize by Mike Fenton 3 winner, Bob Ebdon – a real A-team to keep us all on our toes! Next The Fable of the Autoharp... by Patrick O’Sullivan 4 on the agenda will be Sore Fingers Easter Week (14th – 19th April) Gargrave Autoharp Festival by Patrick O’Sullivan 6 with the incomparable Karen Mueller and Heather as tutors, before A Heartfelt Thank You attention switches north to Yorkshire at the end of June and a repeat by Drew Smith 9 A Cybermama of UKA’s Gargrave Autoharp Festival (27th to 29th) hosted by Patrick by Nadine Stah White 10 Learning Style.. -

Makers of the Piano, 1700-1820." by Martha Novak Clinkscale Malcolm S

Performance Practice Review Volume 7 Article 8 Number 1 Spring "Makers of the Piano, 1700-1820." By Martha Novak Clinkscale Malcolm S. Cole Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Cole, Malcolm S. (1994) ""Makers of the Piano, 1700-1820." By Martha Novak Clinkscale," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 7: No. 1, Article 8. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199407.01.08 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol7/iss1/8 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book Reviews Martha Novak Clinkscale. Makers of the Piano, 1700-1820. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. xv, 403 p. ISBN 0-19-816323-1. "Open the door, and let us go into your room. I am most anxious to see your pianofortes."1 In this letter of October 14, 1777, Mozart renders a lively account of his meeting in Augsburg with the celebrated keyboard builder Johann Andreas Stein. In Makers of the Piano, 1700-1820, Martha Novak Clinkscale opens the door to some 2200 surviving pianos by almost 870 individuals or firms. Framing "The Makers and the Pianos" section, the heart of the book, are important introductory matters, a comprehensive bibliography, an annotated list of collections worldwide, and a useful glossary. Makers of the Piano is a dictionary of musical instruments and builders. The opening installment in printed format of a computerized relational database (Early Pianos 1720-1860) containing at present over 4000 pianos and several hundred makers, it is indeed, as proclaimed on the dust jacket, "the first book to present details about all known extant pianos built during the earliest years of the instrument's existence." Organization is alphabetical by maker, from John Adlam to Johann Christoph Zumpe, probably London's first builder.