The Wharf: a Monumental Waterfront Urban Regeneration Development in Washington, DC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Air and Space Museum to Undergo Major Construction

January 2018 Circulation 13,000 FREE PAUL "SOUTH" TAYLOR DESERVES HIS PRAISE Page 2 CIRCULATOR Coming Back to SW? Page 3 Air and Space Museum to Undergo Major Construction OP-ED: he first major construction project years. • $250 million: fundraising goal AMIDON IS THE for the Air and Space Museum will • All 23 galleries and presentation spac- • 1,441: newly displayed artifacts T start this summer. es will be transformed. • 7: years scheduled for completion PLACE TO BE • The museum is raising $250 mil- • 0: days closed for construction The facts: lion through private donations to fund The museum has released artist ren- Page 4 • This is the first major construction the future galleries. derings highlighting the exciting changes project for the building in Southwest • The project also includes the complete to come. These renderings (above) rep- Washington, DC, since its opening 41 re-facing of the exterior stone, replace- resent the first nine galleries scheduled years ago. ment of outdated mechanical systems, for renovation. New galleries will be orga- • Visitors will start seeing changes to the and other improvements supported by nized by theme, helping you find your museum in summer 2018. federal funding. favorite stories and make connections COMMUNITY • The museum will remain open through across eras. the project by dividing the construction By the numbers: All information and images courtesy of CALENDAR into two major phases. • 13,000 – stone slabs replaced the Smithsonian National Air and Space • The project is scheduled to take seven • 23: new galleries or presentation spaces Museum. Page 6 MRS. THURGOOD MARSHALL & HER HUSBAND Page 8 FIND US ONLINE AT THESOUTHWESTER.COM, OR @THESOUTHWESTER @THESOUTHWESTER /THESOUTHWESTERDC Published by the Southwest Neighborhood Assembly, Inc. -

The Most Exciting Neighborhood in the History of the Nation's Capital

where DC meets waterfront experiences The Most Exciting Neighborhood in the History of the Nation’s Capital The Wharf is reestablishing Washington, DC, as a true DINE, SEE A SHOW & SHOP AT THE WHARF waterfront city and destination. This remarkable mile-long The best in dining and entertainment are finding a new home at neighborhood along the Washington Channel of the Potomac The Wharf, which offers more than 20 restaurants and food River brings dazzling water views, hot new restaurants, year- concepts from fine dining to casual cafes and on-the-go round entertainment, and waterside style all together in one gourmet on the waterfront. The reimagined Wharf stays true to inspiring location. The Wharf, situated along the District of its roots with the renovation and expansion of DC’s iconic Columbia’s Southwest Waterfront just blocks south of the Municipal Fish Market, the oldest continuously operating fish National Mall, is easily accessible to the region. Opened in market in the US. In addition, The Wharf features iconic shops October 2017, The Wharf features world-class residences, and convenient services including Politics and Prose, District offices, hotels, shops, restaurants, cultural, private event, Hardware and Bike, Anchor on board with West Marine, Harper marina, and public spaces, including waterfront parks, Macaw, and more. promenades, piers, and docks. Phase 2 delivers in 2022. The Wharf is also becoming DC’s premier entertainment EXPLORE THE WHARF destination. The entertainment scene is anchored by The Anthem, a concert and events venue with a variable capacity The Wharf reconnects Washington, DC, to its waterfront from 2,500 to 6,000 people that is operated by IMP, owners of on the Potomac River. -

Post-COVID-19 World a Manifesto for a Better Post-COVID-19 World

SOCI AL INN O VATI O N IN THE FACE O F T H E COVID- 1 9 PANDEM I C Winning contribution for the call for inspiration of Belgium's Young Academy “Anticipating life after the COVID-19 pandemic" A Manifesto for a Better Post-COVID-19 World A Manifesto for a Better Post-COVID-19 World SOCIAL INNOVATION Authors IN THE FACE OF THE Abdellatif Atif (Free university of Bolzano, Italy), Carlos Escarpenter Martinez, Canavate (Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Spain; KU Leuven, Belgium), Christine Muchiri Njuhi (Technical University of Kenya, Nairobi, COVID-19 PANDEMIC Kenya), Clara Medina García (KU Leuven, Belgium; UCM, Spain), Dawit Gebrehiwet (Ethiopian Institute of Technology - Mekelle University, Ethiopia), Dora Bellamacina (Mediterranean University of Reggio Calabria, Italy), Eshete Sitotaw (Addis Ababa City Plan and Develop- INSIST Cahier 4 ment Commission, Ethiopia), Farzana Yasmin (KU Leuven, Belgium), Federica Rotondo (Politecnico of Turin, Italy), Frank Moulaert (KU Leuven, June 2020 Belgium), Genaro Alva Zevallos (IMSDP Network), Grace Valasa (Techni- cal University of Kenya, Kenya), Hongkai Chen (KU Leuven, Belgium), Isye Susana Nurhasanah (KU Leuven, Belgium; Institut Teknologi Sumatera, Indonesia), Joan Nyagwalla Otieno (KU Leuven, Belgium; Technical University of Kenya), Juliet Njeri Ritta (Technical University of Kenya), This Manifesto is part of the working paper “Social innovation in Kammerhofer Arthur (KU Leuven, Belgium; TU Wien, Austria), Marjan the face of the COVID-19 pandemic”, drafted in the frame of Marjanovic (Bartlett -

Southwest Waterfront Redevelopment

SOUTHWEST WATERFRONT REDEVELOPMENT STAGE 2 PUD – PHASE I HOFFMAN-STRUEVER WATERFRONT, L.L.C. APPLICATION TO THE D.C. ZONING COMMISSION FOR A SECOND STAGE PLANNED UNIT DEVELOPMENT STATEMENT OF THE APPLICANT February 3, 2012 Submitted by: HOLLAND & KNIGHT LLP 2099 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Suite 100 Washington, D.C. 20006 (202) 955-3000 Norman M. Glasgow, Jr. Mary Carolyn Brown ZONING COMMISSION Counsel for the Applicant District of Columbia ZONING COMMISSION Case No. 11-03A District of Columbia CASE NO.11-03A 2 EXHIBIT NO.2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE .......................................................................................................................................... iii DEVELOPMENT TEAM ...................................................................................................................... v LIST OF EXHIBITS ........................................................................................................................... viii I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 1 A. Overview ......................................................................................................................... 1 B. The Applicant and Development Team .......................................................................... 2 II. APPROVED STAGE 1 PUD DEVELOPMENT PARAMETER ............................................................. 4 III. PROPOSED VERTICAL DEVELOPMENT....................................................................................... -

International Business Guide

WASHINGTON, DC INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS GUIDE Contents 1 Welcome Letter — Mayor Muriel Bowser 2 Welcome Letter — DC Chamber of Commerce President & CEO Vincent Orange 3 Introduction 5 Why Washington, DC? 6 A Powerful Economy Infographic8 Awards and Recognition 9 Washington, DC — Demographics 11 Washington, DC — Economy 12 Federal Government 12 Retail and Federal Contractors 13 Real Estate and Construction 12 Professional and Business Services 13 Higher Education and Healthcare 12 Technology and Innovation 13 Creative Economy 12 Hospitality and Tourism 15 Washington, DC — An Obvious Choice For International Companies 16 The District — Map 19 Washington, DC — Wards 25 Establishing A Business in Washington, DC 25 Business Registration 27 Office Space 27 Permits and Licenses 27 Business and Professional Services 27 Finding Talent 27 Small Business Services 27 Taxes 27 Employment-related Visas 29 Business Resources 31 Business Incentives and Assistance 32 DC Government by the Letter / Acknowledgements D C C H A M B E R O F C O M M E R C E Dear Investor: Washington, DC, is a thriving global marketplace. With one of the most educated workforces in the country, stable economic growth, established research institutions, and a business-friendly government, it is no surprise the District of Columbia has experienced significant growth and transformation over the past decade. I am excited to present you with the second edition of the Washington, DC International Business Guide. This book highlights specific business justifications for expanding into the nation’s capital and guides foreign companies on how to establish a presence in Washington, DC. In these pages, you will find background on our strongest business sectors, economic indicators, and foreign direct investment trends. -

District Columbia

PUBLIC EDUCATION FACILITIES MASTER PLAN for the Appendices B - I DISTRICT of COLUMBIA AYERS SAINT GROSS ARCHITECTS + PLANNERS | FIELDNG NAIR INTERNATIONAL TABLE OF CONTENTS APPENDIX A: School Listing (See Master Plan) APPENDIX B: DCPS and Charter Schools Listing By Neighborhood Cluster ..................................... 1 APPENDIX C: Complete Enrollment, Capacity and Utilization Study ............................................... 7 APPENDIX D: Complete Population and Enrollment Forecast Study ............................................... 29 APPENDIX E: Demographic Analysis ................................................................................................ 51 APPENDIX F: Cluster Demographic Summary .................................................................................. 63 APPENDIX G: Complete Facility Condition, Quality and Efficacy Study ............................................ 157 APPENDIX H: DCPS Educational Facilities Effectiveness Instrument (EFEI) ...................................... 195 APPENDIX I: Neighborhood Attendance Participation .................................................................... 311 Cover Photograph: Capital City Public Charter School by Drew Angerer APPENDIX B: DCPS AND CHARTER SCHOOLS LISTING BY NEIGHBORHOOD CLUSTER Cluster Cluster Name DCPS Schools PCS Schools Number • Oyster-Adams Bilingual School (Adams) Kalorama Heights, Adams (Lower) 1 • Education Strengthens Families (Esf) PCS Morgan, Lanier Heights • H.D. Cooke Elementary School • Marie Reed Elementary School -

Social Innovation Research in the European Union Approaches, fi Ndings and Future Directions POLICY REVIEW

Social innovation research in the European Union Approaches, fi ndings and future directions POLICY REVIEW Research and Innovation EUROPEAN COMMISSION Directorate-General for Research & Innovation Directorate B -- European Research Area Unit B.5 -- Social Sciences and Humanities Contact: Heiko Prange-Gstöhl European Commission B-1049 Brussels E-mail: [email protected] EUROPEAN COMMISSION Social innovation research in the European Union Approaches, findings and future directions POLICY REVIEW Directorate-General for Research and Innovation 2013 Socio-economic Sciences and Humanities EUR 25996 EN EUROPE DIRECT is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union. Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). LEGAL NOTICE Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of the following information. The views expressed in this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission. More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2013 ISBN 978-92-79-30491-0 doi:10.2777/12639 © European Union, 2013 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Images © Éva Széll, 2013 Printed in France Printed on totally chlorine-free bleached paper (TCF) CONTENTS 3 Contents FOREWORD ......................................................................................................................................................................................4 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY..............................................................................................................................................................6 1. -

Regional Analysis and the New International Division of Labor Studies in Applied Regional Science

REGIONAL ANALYSIS AND THE NEW INTERNATIONAL DIVISION OF LABOR STUDIES IN APPLIED REGIONAL SCIENCE Editor-in-Chief: P. NUKAMP, Free University, Amsterdam Editorial Board: A.E. ANDERSSON, University of Umea, Umea W. ISARD, Cornell University, Ithaca L.H. KLAASSEN, Netherlands Economic Institute, Rotterdam I. MASSER, University of Sheffield, Sheffield N. SAKASHlTA, University of Tsukuba, Sakura REGIONAL ANALYSIS AND THE NEW INTERNATIONAL DIVISION OF LABOR Applications of a Political Economy Approach Edited By FRANK MOULAERT Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Belgium and PATRICIA WILSON SALINAS University of Texas Austin, Texas FOREWORD BY JOHN FRImMAN KLUWER-NIJHOFF PUBLISHING Boston The Hague London Distributors for North America: Kluwer· Nijhoff Publishing Kluwer Boston, Inc. 190 Old Derby Street Hingham, Massachusetts 02043, U.S.A. Distributors outside North America: Kluwer Academic Publishers Group Distribution Centre P.O. Box 322 3300AH Dordrecht, The Netherlands Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Regional analysis and the new international division of labor. (Studies in applied regional science) Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. International economic relations - Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Regional economics-Addresses, essays, lectures. 3. Space in economics-Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Moulaert, Frank. II. Salinas, Patricia Wilson. III. Series. HF141.R418 338'.06 82-15342 ISBN-13: 978-94-009-74\\-\ e-ISBN-13: 978-94-009-7409-8 001: 10.1007/978-94-009-7409-8 Copyright © 1983 by Kluwer· Nijhoff Publishing No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. Aan Greet and To Nelson First versions of most of the chapters in this book were presented at the sessions on 'Regional Political Economy' at the first world conference of the World University (held at Harvard University, Cambridge, USA, June 6-June 23 1980). -

Potomac Park

46 MONUMENTAL CORE FRAMEWORK PLAN EDAW Enhance the Waterfront Experience POTOMAC PARK Potomac Park can be reimagined as a unique Washington destination: a prestigious location extending from the National Mall; a setting of extraordinary beauty and sweeping waterfront vistas; an opportunity for active uses and peaceful solitude; a resource with extensive acreage for multiple uses; and a shoreline that showcases environmental stewardship. Located at the edge of a dense urban center, Potomac Park should be an easily accessible place that provides opportunities for water-oriented recreation, commemoration, and celebration in a setting that preserves the scenic landscape. The park offers great potential to relieve pressure on the historic and fragile open space of the National Mall, a vulnerable resource that is increasingly overburdened with demands for large public gatherings, active sport fields, everyday recreation, and new memorials. Potomac Park and its shoreline should offer a range of activities for the enjoyment of all. Some areas should accommodate festivals, concerts, and competitive recreational activities, while other areas should be quiet and pastoral to support picnics under a tree, paddling on the river, and other leisure pastimes. The park should be connected with the region and with local neighborhoods. MONUMENTAL CORE FRAMEWORK PLAN 47 ENHANCE THE WATERFRONT EXPERIENCE POTOMAC PARK Context Potomac Park is a relatively recent addition to Ohio Drive parallels the walkway, provides vehicular Washington. In the early years of the city it was an access, and is used by bicyclists, runners, and skaters. area of tidal marshes. As upstream forests were cut The northern portion of the island includes 25 acres and agricultural activity increased, the Potomac occupied by the National Park Service’s regional River deposited greater amounts of silt around the headquarters, a park maintenance yard, offices for the developing city. -

Ty 2022 Dc Otr Rpta

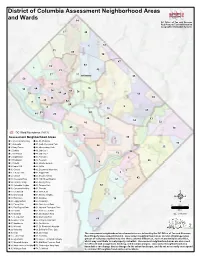

District of Columbia Assessment Neighborhood Areas and Wards 14 DC Office of Tax and Revenue Real Property Tax Administration Geographic Information Systems 27 48 6 51 11 60 12 47 49 53 1 21 42 37 17 35 50 13 7 30 54 15 34 61 36 70 55 24 56 71 38 66 26 4 62 29 31 8 5 19 65 23 40 41 25 44 63 52 10 32 20 18 DC Ward Boundaries (2012) 72 39 Assessment Neighborhood Areas 9 1, American University 36, Mt. Pleasant 33 2, Anacostia 37, North Cleveland Park 46 3, Barry Farms 38, Observatory Circle 22 4, Berkley 39, Old City 1 64 5, Brentwood 40, Old City 2 73 6, Brightwood 41, Palisades 2 7, Brookland 42, Petworth 28 74 8, Burleith 43, Randle Heights 9, Capitol Hill 44, NoMa 10, Central 46, Southwest Waterfront 3 11, Chevy Chase 47, Riggs Park 3 12, Chillum 48, Shepherd Park 43 13, Cleveland Park 49, 16th Street Heights 67 14, Colonial Village 50, Spring Valley 15, Columbia Heights 51, Takoma Park 68 16, Congress Heights 52, Trinidad 17, Crestwood 53, Wakefield 18, Deanwood 54, Wesley Heights 19, Eckington 55, Woodley 16 20, Foggy Bottom 56, Woodridge 4 21, Forest Hills 60, Rock Creek Park 0 0.5 1 22, Fort Dupont Park 61, National Zoological Park 23, Foxhall 62, Rock Creek Park Miles 24, Garfield 63, DC Stadium Area Date: 2/19/2021 25, Georgetown 64, Anacostia Park 69 26, Glover Park 65, National Arboretum 27, Hawthorne 66, Fort Lincoln 28, Hillcrest 67, St. -

2014 Transit Development Plan Executive Summary

ES Executive Summary ES 1 Introduction The 2011 DC Circulator Transit Development Plan (TDP), the first such plan for the Circulator in its nearly 10-year history, established the need for a TDP update every three years. This report fulfills that directive and will guide the future growth of the DC Circulator bus system by keeping the existing system, and future growth of the system, current and aligned with demand and development in DC. Since beginning service in 2005, the Circulator has grown from an initial two routes to a more extensive network of five routes. The Circulator is known for its strong brand, identified by: 6 Distinctive, comfortable buses. 6 High‐frequency service (all day, 10‐minute headways). 6 Connections to key activity center and transit modes. 6 Easy to understand routes. 6 Simple, affordable fare structure. In 2013, the DC Circulator provided more than 5.6 million trips and now operates a fleet of 49 buses. It is the fourth largest bus system in the region in terms of ridership. This success has led to increased demand for additional Circulator service, and the purpose of this plan is to provide a basis for directing that growth and continually improving the existing system. As such, this plan accomplishes the following objectives: 6 Provide a transparent planning and decision‐making process through a broad outreach and participation process. 6 Update citywide land use, demographic, development data, in addition to data and plans for other transit services, in order to identify corridors that support Circulator service and warrant all-day 10-minute headways. -

Agency Value of Incentive Recipient Subtype/Description Ward

Appendix III Detailed Economic Development Incentives by Ward Ward Subtype/Description Recipient Incentive Value of Agency Type Incentive 1 Portner Flats Portner Flats LLC Revenue Bond $27,000,000 DCHFA Issuance Ward Activity Not Impacting FY16 Budget or Revenue $27,000,000 1 1805 7TH ST NW 100 United Negro College Tax Abatement $424,360 (None - Tax Fund Inc Expenditure) 1 Affordable Housing Project DC Coalition for Grants $210,000 DHCD Financing Housing 1 Bancroft Elementary School Ayers/Saint/Gross Inc. Expenditures on $934,018 DCPS Modernization Contracts 1 Bancroft Elementary School Blue Skye Construction, Expenditures on $3,153,789 DCPS Modernization LLC Contracts 1 Campbell Heights Project Paul Laurence Dunbar Tax Exemption $225,754 (None - Tax Apartments LP Expenditure) 1 Commercial Clean Teams Adams Morgan Grants $132,000 DSLBD Partnership 1 Community Revitalization Housing Counseling Grants $161,399 DHCD Services Inc 1 Community Revitalization Greater Washington Grants $492,000 DHCD Urban League 1 Great Streets Initiative Salsa with Silvia, LLC Grants $85,000 DMPED 1 Great Streets Initiative Wandawoman Grants $50,000 DMPED Enterprises, Inc 1 Howard Theater TIF (see Bondholders TIF Debt Misc Funds "combined TIF Debt") Service 1 Jubilee Housing Residential Jubilee Housing Limited Tax Exemption $216,922 (None - Tax Partnership Expenditure) 1 Neighborhood Based Greater Washington Grants $123,121 DHCD Activities Urban League District of Columbia Unified Economic Development Report: FY16 Year-End Page 1 of 29 in Appendix III Appendix