Nitoring Rogramme 2006-08

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislative Affairs

CCBS – LEGISLATIVE AFFAIRS 17/02/2015-25/02/2015 Committees Wednesday 18 February 2015 Committee for Finance and Personnel EU Funding Programmes: PEACE IV and INTERREG 5A - Briefing from DFP & Special EU Programmes Body (SEUPB) • Mr Frank Duffy, DFP – Head of EU Division • Mr Dominic McCullough, DFP – Head of North/South Policy and Programmes Unit • Mr Pat Colgan, Special EU Programmes Body – Chief Executive • Mr Shaun Henry, Special EU Programmes Body – Director of the Managing Authority Hansard: http://data.niassembly.gov.uk/HansardXml/committee-12149.pdf YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DLXY24wt0YA Summary: At a briefing to the Committee for Finance and Personnel on ‘EU Funding Programmes: PEACE IV and INTERREG 5A’ from DFP & Special EU Programmes Body (SEUPB) focused on providing an update on the key areas of interest, including the Peace and INTERREG programmes, and on issues that were raised before in Committee, which are the administrative simplification of the new programme and the implementation of the existing programmes, from 2007 to 2013. Issues of note: Mr Frank Duffy (Department of Finance and Personnel): “At the previous Committee meeting in April, members raised concerns about the application process for the cross-border programmes, in particular work being undertaken to reduce the time taken for a decision on funding applications, and the perceived bureaucracy that went along with that. At the time, I identified that our aim was to reduce considerably the application process time, and I undertook to do so by at least one third. Therefore, to update the Committee on that, thanks to some very engaged and constructive discussions that DFP has had with DPER and SEUPB, we have reached agreement for a process to be 1 undertaken from start to finish in 36 weeks. -

Four Nations Impartiality Review: an Analysis of Reporting Devolution

APPENDIX A Four Nations Impartiality Review: An analysis of reporting devolution Report authors Prof. Justin Lewis Dr. Stephen Cushion Dr. Chris Groves Lucy Bennett Sally Reardon Emma Wilkins Rebecca Williams Cardiff School of Journalism, Media and Cultural Studies, Cardiff University 1 Contents Page 1. Introduction and Overview 2. General sample 3. Case studies 4. Reporting the 2007 elections 5. Current Affairs Coverage 2007 6. Five Live Phone-In Programmes (Oct-Nov and Election Samples) 7. Devolution Stories on BBC Six O’Clock News and 6.30pm Opt- Outs 8. Omissions 9. Devolution online: Focus groups 10. Bibliography 11. Appendix 2 1. Introduction and Overview The scope of the study The central aim of the study was to examine how devolution is reported in UK-wide BBC network television and radio news, BBC network factual programmes and BBC online news. This analysis took place within the broad framework of questions about impartiality and accuracy, and asked whether the coverage of the four nations is balanced, accurate and helpful in understanding the new political world of devolved government. The focus of the study fell on the coverage of politics in the broadest sense, including the impact of specific policies and debates over the future of devolution, rather than being limited to the reporting of the everyday business of politics within Westminster, Holyrood, Cardiff Bay or Stormont. We conducted two substantive pieces of content analysis. The first was based on a sample of four weeks of news coverage gathered during an eight week period in October and November 2007. This involved 4,687 news items across a wide range of BBC and non-BBC outlets. -

A Fresh Start? the Northern Ireland Assembly Election 2016

A fresh start? The Northern Ireland Assembly election 2016 Matthews, N., & Pow, J. (2017). A fresh start? The Northern Ireland Assembly election 2016. Irish Political Studies, 32(2), 311-326. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907184.2016.1255202 Published in: Irish Political Studies Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2016 Taylor & Francis. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:30. Sep. 2021 A fresh start? The Northern Ireland Assembly election 2016 NEIL MATTHEWS1 & JAMES POW2 Paper prepared for Irish Political Studies Date accepted: 20 October 2016 1 School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. Correspondence address: School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, University of Bristol, 11 Priory Road, Bristol BS8 1TU, UK. -

Northern Ireland Policing Board Annual Report and Accounts Together with the Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General

ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE PERIOD 1 APRIL 2008 - 31 MARCH 2009 CORPORATE VISION To secure for all the people of Northern Ireland an effective, efficient, impartial, representative and accountable police service which will secure the confidence of the whole community by reducing crime and the fear of crime. ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS FOR THE PERIOD 1 APRIL 2008 - 31 MARCH 2009 Northern Ireland Policing Board Annual Report and Accounts together with the Report of the Comptroller and Auditor General. Presented to Parliament pursuant to Paragraph 7(3) b of Schedule 2 of the Police (NI) Act 2000. Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 15 July 2009. HC 674 London: The Stationery Office £26.60 © Crown Copyright 2009 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and other departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. For any other use of this material please write to Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU or e-mail: [email protected] ISBN 9780102948653 Contents Page 03 01 CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD 04 02 CHIEF EXECUTIVE’S FOREWORD 09 03 MEMBERSHIP OF THE NORTHERN IRELAND POLICING BOARD 11 04 MANAGEMENT COMMENTARY 14 Background and principal -

A Year in Review, the Year Ahead

2018: A YEAR IN REVIEW, 2019: THE YEAR AHEAD Foreword from Rt Hon Patricia Hewitt, Senior Adviser, FTI Consulting 2018 was the most unpredictable and tumultuous year in politics … since 2017. Which was the most unpredictable and tumultuous year in politics … since 2016. And there’s no sign of let-up as we move into 2019. The unresolved questions of Brexit - how? when? whether at all? - will inevitably dominate the coming year. Even if Theresa May brings back from Brussels a new political declaration sufficiently compelling to command a majority in Parliament - a highly unlikely prospect at the time of writing - the end of March will mean the start of a fresh, complex round of negotiations on a future trade deal, conducted under the shadow of the Irish backstop. For most people, that would be preferable to the collapse of Mrs May’s deal and, almost inevitably, the collapse of her government and a subsequent constitutional crisis. Faced with the choice between revoking Article 50 or leaving the European Union (EU) without a deal, the Commons could well produce a majority for a new referendum. Under the pressure of a leadership contest, the personal and political rancour in the Conservative Party could finally break apart Europe’s hitherto most successful party of government. A no-confidence vote that would be defeated today could command enough votes from the Brexiteers’ kamikaze tendency to force another General Election. And Labour - with most of its moderates MPs replaced by Corbynistas in last-minute candidate selections - could win on a ‘cake and eat it’ manifesto of a Brexit that would end free movement but provide frictionless trade (Irish backstop, anyone?). -

Committee for Finance Meeting Minutes of Proceedings 27 January

COMMITTEE FOR FINANCE MINUTES OF PROCEEDINGS WEDNESDAY, 27 JANUARY 2021 Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings, Belfast Present: Dr Steve Aiken OBE MLA (Chairperson) Mr Paul Frew MLA (Deputy Chairperson) Mr Jim Allister MLA Mr Matthew O’Toole MLA Mr Jim Wells MLA Present by Video-conference: Mr Pat Catney MLA Ms Jemma Dolan MLA Mr Philip McGuigan MLA Mr Maolíosa McHugh MLA Apologies: None In Attendance: Mr Peter McCallion (Assembly Clerk) Mr Phil Pateman (Assistant Assembly Clerk) Mr Neil Sedgewick (Clerical Supervisor) Ms Heather Graham (Clerical Officer) The meeting commenced at 2:01pm in public session. The Chairperson conveyed the Committee’s deepest sympathy to Mr McHugh following the recent death of his mother Mr McHugh expressed his thanks to Members for their kind consideration. 1. Apologies There were no apologies. No notices were received from any Member of a delegation of their vote to another Member as per Temporary Standing Order 115(6). 1 2. Declaration of Interests There were no declarations of interest. Agreed: The Committee agreed that the Chairperson would write to the Chairperson’s Liaison Group and the Northern Ireland Assembly Commission to express concerns in respect of difficulties arising from the use of the Assembly’s video-conferencing facility which can sometimes adversely affect Members’ participation in committee meetings. 3. Draft Minutes The Committee considered the minutes of the meeting held on Wednesday, 20 January 2021. Agreed: The Committee agreed the minutes of the meeting held on Wednesday, 20 January 2021. Mr Frew joined the meeting at 2:04pm. 4. Matters Arising There were no matters arising. -

LE19 - a Turning of the Tide? Report of Local Elections in Northern Ireland, 2019

#LE19 - a turning of the tide? Report of local elections in Northern Ireland, 2019 Whitten, L. (2019). #LE19 - a turning of the tide? Report of local elections in Northern Ireland, 2019. Irish Political Studies, 35(1), 61-79. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907184.2019.1651294 Published in: Irish Political Studies Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2019 Political Studies Association of Ireland.. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:29. Sep. 2021 #LE19 – a turning of the tide? Report of Local Elections in Northern Ireland, 2019 Lisa Claire Whitten1 Queen’s University Belfast Abstract Otherwise routine local elections in Northern Ireland on 2 May 2019 were bestowed unusual significance by exceptional circumstance. -

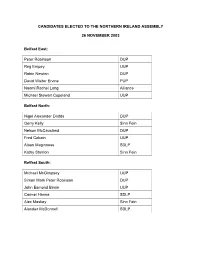

Peter Robinson DUP Reg Empey UUP Robin Newton DUP David Walter Ervine PUP Naomi Rachel Long Alliance Michael Stewart Copeland UUP

CANDIDATES ELECTED TO THE NORTHERN IRELAND ASSEMBLY 26 NOVEMBER 2003 Belfast East: Peter Robinson DUP Reg Empey UUP Robin Newton DUP David Walter Ervine PUP Naomi Rachel Long Alliance Michael Stewart Copeland UUP Belfast North: Nigel Alexander Dodds DUP Gerry Kelly Sinn Fein Nelson McCausland DUP Fred Cobain UUP Alban Maginness SDLP Kathy Stanton Sinn Fein Belfast South: Michael McGimpsey UUP Simon Mark Peter Robinson DUP John Esmond Birnie UUP Carmel Hanna SDLP Alex Maskey Sinn Fein Alasdair McDonnell SDLP Belfast West: Gerry Adams Sinn Fein Alex Atwood SDLP Bairbre de Brún Sinn Fein Fra McCann Sinn Fein Michael Ferguson Sinn Fein Diane Dodds DUP East Antrim: Roy Beggs UUP Sammy Wilson DUP Ken Robinson UUP Sean Neeson Alliance David William Hilditch DUP Thomas George Dawson DUP East Londonderry: Gregory Campbell DUP David McClarty UUP Francis Brolly Sinn Fein George Robinson DUP Norman Hillis UUP John Dallat SDLP Fermanagh and South Tyrone: Thomas Beatty (Tom) Elliott UUP Arlene Isobel Foster DUP* Tommy Gallagher SDLP Michelle Gildernew Sinn Fein Maurice Morrow DUP Hugh Thomas O’Reilly Sinn Fein * Elected as UUP candidate, became a member of the DUP with effect from 15 January 2004 Foyle: John Mark Durkan SDLP William Hay DUP Mitchel McLaughlin Sinn Fein Mary Bradley SDLP Pat Ramsey SDLP Mary Nelis Sinn Fein Lagan Valley: Jeffrey Mark Donaldson DUP* Edwin Cecil Poots DUP Billy Bell UUP Seamus Anthony Close Alliance Patricia Lewsley SDLP Norah Jeanette Beare DUP* * Elected as UUP candidate, became a member of the DUP with effect from -

Members' Office Costs Allowance 2003-2004

Members' Office Costs Allowance 2003-2004 Campbell, Gregory Account Name Date Amount Expenditure Description Supplier Name Members Equipment Maintenance 08-Jul-03 £49.65 Equipment Maintenance CHUBB NI LTD Members Office - Rent 09-Apr-03 £1,050.00 Rent NORTH WEST PROPERTY MANAGEMENT Members Office - Rent 09-Apr-03 £50.00 Rent EAST L'DERRY ASSOC. DUP Members Office - Rent 07-May-03 £1,050.00 Rent NORTH WEST PROPERTY MANAGEMENT Members Office - Rent 07-May-03 £50.00 Rent EAST L'DERRY ASSOC. DUP Members Office - Rent 05-Jun-03 £1,050.00 Rent NORTH WEST PROPERTY MANAGEMENT Members Office - Rent 05-Jun-03 £50.00 Rent EAST L'DERRY ASSOC. DUP Members Office - Rent 02-Jul-03 £1,050.00 Rent NORTH WEST PROPERTY MANAGEMENT Members Office - Rent 02-Jul-03 £50.00 Rent EAST L'DERRY ASSOC. DUP Members Office - Rent 05-Aug-03 £1,050.00 Rent NORTH WEST PROPERTY MANAGEMENT Members Office - Rent 05-Aug-03 £50.00 Rent EAST L'DERRY ASSOC. DUP Members Office - Rent 04-Sep-03 £1,050.00 Rent NORTH WEST PROPERTY MANAGEMENT Members Office - Rent 04-Sep-03 £50.00 Rent EAST L'DERRY ASSOC. DUP Members Office - Rent 01-Oct-03 £1,050.00 Rent NORTH WEST PROPERTY MANAGEMENT Members Office - Rent 01-Oct-03 £50.00 Rent EAST L'DERRY ASSOC. DUP Members Office - Rent 01-Nov-03 £1,050.00 Rent NORTH WEST PROPERTY MANAGEMENT Members Office - Rent 01-Nov-03 £50.00 Rent EAST L'DERRY ASSOC. DUP Members Office - Rent 01-Dec-03 £1,050.00 Rent NORTH WEST PROPERTY MANAGEMENT Members Office - Rent 01-Dec-03 £50.00 Rent EAST L'DERRY ASSOC. -

The Flags Dispute: Anatomy of a Protest

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274691563 The Flags Dispute: Anatomy of a Protest Book · December 2014 CITATIONS READS 5 82 6 authors, including: Dominic Bryan Katy Hayward Queen's University Belfast Queen's University Belfast 33 PUBLICATIONS 94 CITATIONS 51 PUBLICATIONS 137 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Peter Shirlow University of Liverpool 109 PUBLICATIONS 1,433 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Brexit and the Border View project devolution View project All content following this page was uploaded by Dominic Bryan on 08 April 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. The Flag Dispute: Anatomy of a Protest Full Report Paul Nolan Dominic Bryan Clare Dwyer Katy Hayward Katy Radford & Peter Shirlow December 2014 Supported by the Community Relations Council & the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (Ireland) Published by Queen’s University Belfast ISBN 9781909131248 Cover image: © Pacemaker Press. 3 Acknowledgements The authors of this report are extremely grateful to the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the Community Relations Council for funding this research project and its publication. A huge debt of gratitude is also due to those who gave their time to be interviewed, and for the honesty and candour with which they related their experiences - these were often quite emotive experiences. The Institute for Conflict Research (ICR) was commissioned to undertake the interviews presented within this report. These interviews were conducted with great care and skill with ICR capturing many voices which we hope have been represented fairly and accurately within this publication. -

“A Peace of Sorts”: a Cultural History of the Belfast Agreement, 1998 to 2007 Eamonn Mcnamara

“A Peace of Sorts”: A Cultural History of the Belfast Agreement, 1998 to 2007 Eamonn McNamara A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy, Australian National University, March 2017 Declaration ii Acknowledgements I would first like to thank Professor Nicholas Brown who agreed to supervise me back in October 2014. Your generosity, insight, patience and hard work have made this thesis what it is. I would also like to thank Dr Ben Mercer, your helpful and perceptive insights not only contributed enormously to my thesis, but helped fund my research by hiring and mentoring me as a tutor. Thank you to Emeritus Professor Elizabeth Malcolm whose knowledge and experience thoroughly enhanced this thesis. I could not have asked for a better panel. I would also like to thank the academic and administrative staff of the ANU’s School of History for their encouragement and support, in Monday afternoon tea, seminars throughout my candidature and especially useful feedback during my Thesis Proposal and Pre-Submission Presentations. I would like to thank the McClay Library at Queen’s University Belfast for allowing me access to their collections and the generous staff of the Linen Hall Library, Belfast City Library and Belfast’s Newspaper Library for all their help. Also thanks to my local libraries, the NLA and the ANU’s Chifley and Menzies libraries. A big thank you to Niamh Baker of the BBC Archives in Belfast for allowing me access to the collection. I would also like to acknowledge Bertie Ahern, Seán Neeson and John Lindsay for their insightful interviews and conversations that added a personal dimension to this thesis. -

Modern Library and Information Science

MCQs for LIS ABBREVIATIONS, ACRONYMS 1. What is the full form of IATLIS? (a) International Association of Trade Unions of Library & Information Science (b) Indian Association of Teachers in Library & Information Science (c) Indian Airlines Technical Lower Intelligence Services (d) Indian Air Traffic Light Information and Signal 2. IIA founded in USA in 1968 stands for (a) Integrated Industry Association (b) Information Industry Association (c) Integrated Illiteracy eradication Association (d) Institute of Information Association 3. BSO in classification stands for (a) Basic Subject of Organisation (b) Broad System of Ordering (c) Bibliography of Subject Ordering (d) Bibliographic Subject Organisation 4. IPR stands for (a) Indian Press Registration (b) Intellectual Property Right (c) International Property Right (d) Indian Property Regulations 5. NAAC stands for (a) National Accreditation and Authority Council (b) Northern Accreditation and Authorities Committee (c) National Assessment and Accreditation Council (d) Northern Assessment and Accreditation Council 6. ACRL 1 Dr . K.Kamila & Dr. B.Das MCQs for LIS (a) Association of College and Research Libraries (b) All College and Research Libraries (c) Academic Community Research Libraries 7. CILIP (a) Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (b) Community Institute for Library and Information Programmes (c) College level Institute for Library and Information Programmes (d) Centre for Indian Library and Information Professionals 8. SCONUL (a) Society of College National and University Libraries (previously Standing Conference of National and University Libraries) (b) School College National and University Libraries (c) Special Council for National and University Libraries (d) None of these 9. NISCAIR (a) National Institute of Science Communication and Information Resources (b) National Institute of Scientific Cultural and Industrial Research (c) National Institute of Social Cultural and Industrial Research (d) None of the above 10.