What Is New Age Spirituality? 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Science of the Séance: the Scientific Theory of the Spiritualist Movement in Victorian America

1 Hannah Gramson Larry Lipin HIST 491 March 6, 2013 The Science of the Seance: The Scientific Theory of the Spiritualist Movement in Victorian America In 1869, twenty one years after the first “spirit rappings” were heard in the bedroom of two young girls in upstate New York, a well-known Spiritualist medium by the name of Emma Hardinge Britten wrote a book that chronicled the first two decades of a religion she characterized as uniquely American, and what made this religion exceptional was its basis in scientific theory. “[We] are not aware of any other country than America,” Britten claimed, “where a popular religion thus appeals to the reason and requires its votaries to do their own thinking, or of any other denomination than 'American Spiritualists' who base their belief on scientific facts, proven by living witnesses.”1 Britten went on to claim that, as a “unique, concrete, and...isolated movement,” Spiritualism demanded “from historic justice a record as full, complete, and independent, as itself.”2 Yet, despite the best efforts of Spiritualism's followers to carve out a place for it alongside the greatest scientific discoveries in human history, Spiritualism remains a little understood and often mocked religion that, to those who are ignorant 1 Emma Hardinge Britten, Modern American Spiritualism: A Twenty Years' Record of the Communion Between Earth and the World of Spirits,(New York, 1869) 2 Britten, Modern American Spiritualism 2 of it, remains a seemingly paradoxical movement. Although it might be difficult for some to comprehend today, prior to the Civil War, religion and science were not considered adversaries by any means, but rather, were understood to be traveling down a shared path, with ultimately the same destination. -

Mysticism in Indian Philosophy

The Indian Institute of World Culture Basavangudi, Bangalore-4 Transaction No.36 MYSTICISM IN INDIAN PHILOSOPHY BY K. GOPALAKRISHNA RAO Editor, “Jeevana”, Bangalore 1968 Re. 1.00 PREFACE This Transaction is a resume of a lecture delivered at the Indian Institute of World Culture by Sri K. Gopala- Krishna Rao, Poet and Editor, Jeevana, Bangalore. MYSTICISM IN INDIAN PHILOSOPHY Philosophy, Religion, Mysticism arc different pathways to God. Philosophy literally means love of wisdom for intellectuals. It seeks to ascertain the nature of Reality through sense of perception. Religion has a social value more than that of a spiritual value. In its conventional forms it fosters plenty but fails to express the divinity in man. In this sense it is less than a direct encounter with reality. Mysticism denotes that attitude of mind which involves a direct immediate intuitive apprehension of God. It signifies the highest attitude of which man is capable, viz., a beatific contemplation of God and its dissemination in society and world. It is a fruition of man’s highest aspiration as an integral personality satisfying the eternal values of life like truth, goodness, beauty and love. A man who aspires after the mystical life must have an unfaltering and penetrating intellect; he must also have a powerful philosophic imagination. Accurate intellectual thought is a sure accompaniment of mystical experience. Not all mystics need be philosophers, not all mystics need be poets, not all mystics need be Activists, not all mystics lead a life of emotion; but wherever true mysticism is, one of these faculties must predominate. A true life of mysticism teaches a full-fledged morality in the individual and a life of general good in the world. -

An Index to Meditations on the Tarot

AN INDEX TO MEDITATIONS ON THE TAROT Numbers in brackets are page references to Meditations on the Tarot - A Journey into Christian Hermeticism which was published anonymously and posthumously, and dedicated to Our Lady of Chartres (Amity House, New York, 1985 - Element Books, 1991.) Locations of Specific References ANON, Die Grossen Arcana Des Tarot, Herder, Basel, 1983 - second, completely revised German translation of the original French manuscript of Meditations on the Tarot, the first German translation having been published by Anton Hain, Meisenheim, 1972 (325) ANON, Meditations sur les 22 arcanes majeurs du Tarot, Aubier Montaigne, Paris, 1984 - second, revised and complete edition of the author's original text, an edited version of which had already been published by Aubier Montaigne in 1980 ANON, Meditations on the Tarot - A Journey into Christian Hermeticism, Amity House, New York, 1985 ANON, Meditations on the Tarot - A Journey into Christian Hermeticism Element Books, 1991 ANON, Meditations on the Tarot - A Journey into Christian Hermeticism Jeremy Tharcher ANON, Otkrovennye rasskazy strannika dukhovnymn svoimu ottsu - The Way of a Pilgrim, translated by R.M. French, 1954 (XVIV 384, XVIII 515-6) AGRIPPA OF NETTESHEIM, Henry Cornelius, De Incertitudine et Vanitate Scientiarum (XVI 450) AGRIPPA OF NETTESHEIM, Henry Cornelius, De Occulta Philosophia (III 59, XVI 450) AMBELAIN, Robert, La Kabbale pratique, Paris, 1951 (VI 138) AMBELAIN, Robert, Le Martinisme, Paris, 1946 (VIII 185) Saint ANTHONY THE GREAT, Apophthegmata, translated by E. Kadloubovsky & G.E.H. Palmer in Early Fathers from the Philokalia, London, 1954 - though this translation is not entirely followed (XII 307, XV 411, XV 414) APOLLONIUS OF TYANA or Balinas the Wise, The Secret of Creation, c. -

The Deep Horizon

The Matheson Trust The Deep Horizon Stratford Caldecott "Wherever men and women discover a call to the absolute and transcendent, the metaphysical dimension of reality opens up before them: in truth, in beauty, in moral values, in other persons, in being itself, in God. We face a great challenge at the end of this millennium to move from phenomenon to foundation, a step as necessary as it is urgent. We cannot stop short at experience alone; even if experience does reveal the human being's interiority and spirituality, speculative thinking must penetrate to the spiritual core and the gound from which it rises. Therefore, a philosophy which shuns metaphysics would be radically unsuited to the task of mediation in the understanding of Revelation." [i] With such words as these, Pope John Paul II, in his 1998 encyclical letter on Faith and Reason addressed to the bishops of the Catholic Church, calls for a renewal of metaphysics, "because I am convinced that it is the path to be taken in order to move beyond the crisis pervading large sectors of philosophy at the moment, and thus to correct certain mistaken modes of behaviour now widespread in our society". He goes on, "Such a ground for understanding and dialogue is all the more vital nowadays, since the most pressing issues facing humanity - ecology, peace and the co-existence of different races and cultures, for instance - may possibly find a solution if there is a clear and honest collaboration between Christians and the followers of other religions and all those who, while not sharing a religious belief, have at heart the renewal of humanity" [section 104]. -

Spiritualism: a Source of Prevention from Fatal Pandemic (A General Estimate) Dr

International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences, 5(3) May-Jun 2020 |Available online: https://ijels.com/ Spiritualism: A Source of Prevention from Fatal Pandemic (A General Estimate) Dr. Vanshree Godbole Associate Professor, English, Govt. M. L. B. Girl’s P. G. College, Indore, M.P., India Abstract— Spiritualismis a life Spring of Indian Philosophy, Culture and Religion.Philosophy shows the cause for the inescapable experiences of sorrow and suffering that has engulfed mankind today. The period following the outbreak of fatal pandemic Covid -19 has become the age of disillusionment, chaos, disbelief , utter despair, loss, and disorder in an individual’s life. Hinduism is the only religion that is universal, It is a revealed religion, the priceless truth discovered by intuitive spiritual experiences. Need of the hour is to understand the psychology of commonman, his social condition and to help them regain confidence that has shaken the whole human race. Keywords— Spiritualism, disillusionment, fatal, despair, confidence. Spiritualism is a life Spring of Indian Philosophy, Culture The unrest of the age and passion for reform and solution and Religion “Every human being is a potential spirit and to the present day up- rootedness of human race can be represents, as has been well said, ahope of GOD and is not traced in Indian Philosophical system, that includes whole mere fortuitous concourse of episodes like the changing of mankind from all walks of life whether cultured, forms of clouds or patterns of a kalideoscope.”(1) As we ignorant or learned. To quote Dr.Radhakrishnn “Religion know that the literature is replete with the writings of Men, from the beginning, is the bearer of human culture. -

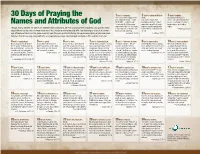

30 Days of Praying the Names and Attributes Of

30 Days of Praying the 1 God is Jehovah. 2 God is Jehovah-M’Kad- 3 God is infinite. The name of the independent, desh. God is beyond measure- self-complete being—“I AM This name means “the ment—we cannot define Him WHO I AM”—only belongs God who sanctifies.” A God by size or amount. He has no Names and Attributes of God to Jehovah God. Our proper separate from all that is evil beginning, no end, and no response to Him is to fall down requires that the people who limits. Though God is infinitely far above our ability to fully understand, He tells us through the Scriptures very specific truths in fear and awe of the One who follow Him be cleansed from —Romans 11:33 about Himself so that we can know what He is like, and be drawn to worship Him. The following is a list of 30 names possesses all authority. all evil. and attributes of God. Use this guide to enrich your time set apart with God by taking one description of Him and medi- —Exodus 3:13-15 —Leviticus 20:7,8 tating on that for one day, along with the accompanying passage. Worship God, focusing on Him and His character. 4 God is omnipotent. 5 God is good. 6 God is love. 7 God is Jehovah-jireh. 8 God is Jehovah-shalom. 9 God is immutable. 10 God is transcendent. This means God is all-power- God is the embodiment of God’s love is so great that He “The God who provides.” Just as “The God of peace.” We are All that God is, He has always We must not think of God ful. -

The Correlation Between Theology and Worship

Running head: THE CORRELATION BETWEEN THEOLOGY AND WORSHIP The Correlation Between Theology and Worship Tyler Thompson A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2018 THE CORRELATION BETWEEN THEOLOGY AND WORSHIP Thompson 1 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Rick Jupin, D.M.A. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Keith Cooper, M.A. Committee Member ______________________________ David Wheeler, P.H.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Chris Nelson, M.F.A. Assistant Honors Director THE CORRELATION BETWEEN THEOLOGY AND WORSHIP Thompson 2 ______________________________ Date Abstract This thesis will address the correlation between theology and worship. Firstly, it will address the process of framing a worldview and how one’s worldview influences his thinking. Secondly, it will contrast flawed views of worship with the biblically defined worship that Christ calls His followers to practice. Thirdly, it will address the impact of theology in the life of a believer and its necessity and practice in the lifestyle of a worship leader. THE CORRELATION BETWEEN THEOLOGY AND WORSHIP Thompson 3 The Correlation Between Worship and Theology Introduction Since creation, mankind was designed to devote its heart, soul, and mind to the Sovereign God of all (Rom. 1:18-20). As an outward sign of this commitment and devotion, mankind would live in accordance with the established, inerrant, and absolute truths of God (Matt. 22:37, John 17:17). Unfortunately, as a consequence of man’s disobedience, many beliefs have arisen which tempt mankind to replace God’s absolute truth as the basis of their worldview (Rom. -

A Glimpse at Spiritualism

A GLIMPSE AT SPIRITUALISM P.V JOITX J. BIRCH ^'*IiE term Spiritualism, as used by philosophical writers denotes the opposite of materialism., but it is also used in a narrower sense to describe the belief that the spiritual world manifests itself by producing in the physical world, effects inexplicable by the known laws of natural science. Many individuals are of the opinion that it is a new doctrine: but in reality the belief in occasional manifesta- tions of a supernatural world has probably existed in the human mind from the most primitive times to the very moment. It has filtered down through the ages under various names. As Haynes states in his book. Spirifttallsiii I'S. Christianity, 'Tt has existed for ages in the midst of heathen darkness, and its presence in savage lands has been marked by no march of progress, bv no advance in civilization, by no development of education, by no illumination of the mental faculties, by no increase of intelligence, but its acceptance has been productive of and coexistent with the most profound ignor- ance, the most barbarous superstitions, the most unspeakable immor- talities, the basest idolatries and the worst atrocities which the world has ever known."' In Egypt, Assyria, Babylon, Greece and Rome such things as astrology, soothsaying, magic, divination, witchcraft and necromancy were common. ]\ loses gives very early in the history of the human race a catalogue of spirit manifestations when he said: "There shall not be found among you any one that maketh his son or his daugh- ter to pass through the fire, or that useth divination, or an observer of times, or an enchanter, or a witch, or a charmer, or a consulter with familiar spirits, or a wizard, or a necromancer. -

Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy

Essays on Indian Philosophy UNIVE'aSITY OF HAWAII Uf,FU:{ Essays on Indian Philosophy SHRI KRISHNA SAKSENA UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS HONOLULU 1970 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 78·114209 Standard Book Number 87022-726-2 Copyright © 1970 by University of Hawaii Press All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Contents The Story of Indian Philosophy 3 Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy 18 Testimony in Indian Philosophy 24 Hinduism 37 Hinduism and Hindu Philosophy 51 The Jain Religion 54 Some Riddles in the Behavior of Gods and Sages in the Epics and the Puranas 64 Autobiography of a Yogi 71 Jainism 73 Svapramanatva and Svapraka!;>atva: An Inconsistency in Kumarila's Philosophy 77 The Nature of Buddhi according to Sankhya-Yoga 82 The Individual in Social Thought and Practice in India 88 Professor Zaehner and the Comparison of Religions 102 A Comparison between the Eastern and Western Portraits of Man in Our Time 117 Acknowledgments The author wishes to make the following acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published essays: "The Story of Indian Philosophy," in A History of Philosophical Systems. edited by Vergilius Ferm. New York:The Philosophical Library, 1950. "Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Are There Any Basic Tenets of Indian Philosophy?" in The Philosophical Quarterly. "Testimony in Indian Philosophy," previously published as "Authority in Indian Philosophy," in Ph ilosophyEast and West. vo!.l,no. 3 (October 1951). "Hinduism," in Studium Generale. no. 10 (1962). "The Jain Religion," previously published as "Jainism," in Religion in the Twentieth Century. edited by Vergilius Ferm. -

Mysticism and Mystical Experiences

1 Mysticism and Mystical Experiences The first issue is simply to identify what mysti cism is. The term derives from the Latin word “mysticus” and ultimately from the Greek “mustikos.”1 The Greek root muo“ ” means “to close or conceal” and hence “hidden.”2 The word came to mean “silent” or “secret,” i.e., doctrines and rituals that should not be revealed to the uninitiated. The adjec tive “mystical” entered the Christian lexicon in the second century when it was adapted by theolo- gians to refer, not to inexpressible experiences of God, but to the mystery of “the divine” in liturgical matters, such as the invisible God being present in sacraments and to the hidden meaning of scriptural passages, i.e., how Christ was actually being referred to in Old Testament passages ostensibly about other things. Thus, theologians spoke of mystical theology and the mystical meaning of the Bible. But at least after the third-century Egyptian theolo- gian Origen, “mystical” could also refer to a contemplative, direct appre- hension of God. The nouns “mystic” and “mysticism” were only invented in the seven teenth century when spirituality was becoming separated from general theology.3 In the modern era, mystical inter pretations of the Bible dropped away in favor of literal readings. At that time, modernity’s focus on the individual also arose. Religion began to become privatized in terms of the primacy of individuals, their beliefs, and their experiences rather than being seen in terms of rituals and institutions. “Religious experiences” also became a distinct category as scholars beginning in Germany tried, in light of science, to find a distinct experi ential element to religion. -

Metamorphoses of a Platonic Theme in Jewish Mysticism

MOSHE IDEL METAMORPHOSES OF A PLATONIC THEME IN JEWISH MYSTICISM 1. KABBALAH AND NEOPLATONISM Both the early Jewish philosophers – Philo of Alexandria and R. Shlomo ibn Gabirol, for example – and the medieval Kabbalists were acquainted with and influenced by Platonic and Neoplatonic sources.1 However, while the medieval philosophers were much more systematic in their borrowing from Neoplatonic sources, especially via their transformations and transmissions from Arabic sources and also but more rarely from Christian sources, the Kabbalists were more sporadic and fragmentary in their appropriation of Neoplatonism. Though the emergence of Kabbalah has often been described by scholars as the synthesis of Neoplatonism and Gnosticism,2 I wonder not only about the role attributed to Gnosticism in the formation of early Kabbalah, but also about the possi- bly exaggerated role assigned to Neoplatonism. Not that I doubt the im- pact of Neoplatonism, but I tend to regard the Neoplatonic elements as somewhat less formative for the early Kabbalah than what is accepted by scholars.3 We may, however, assume a gradual accumulation of Neoplatonic 1 G. Scholem, ‘The Traces of ibn Gabirol in Kabbalah’, Me’assef Soferei Eretz Yisrael (Tel- Aviv, 1960), pp. 160–78 (Hebrew); M. Idel, ‘Jewish Kabbalah and Platonism in the Middle Ages and Renaissance’, in Neoplatonism and Jewish Thought, ed. L. E. Goodman (Albany: SUNY Press, 1993), pp. 319–52; M. Idel, ‘The Magical and Neoplatonic Interpretations of Kabbalah in the Renaissance’, Jewish Thought in the Sixteenth Century, ed. B. D. Cooperman (Cambridge, MA, 1983), pp. 186–242. 2 G. Scholem, Origins of the Kabbalah (tr. -

Mysticism As an Ethical Form of Life: a Wittgensteinian

Mysticism as an Ethical Form of Life: A Wittgensteinian Approach to Ethics in the Mystical Instruction of Saints Teresa of Avila and Ignatius of Loyola in dialogue with Michel de Certeau’s Mystical Science by Matthew Ian Dunch A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Regis College and the Graduate Centre for Theological Studies of the Toronto School of Theology. In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Theology awarded by Regis College and the University of Toronto. © Copyright by Matthew Ian Dunch 2018 Mysticism as an Ethical Form of Life: A Wittgensteinian Approach to Ethics in the Mystical Instruction of Saints Teresa of Avila and Ignatius of Loyola in dialogue with Michel de Certeau’s Mystical Science Matthew Ian Dunch Master of Theology Regis College and the University of Toronto 2018 Abstract This thesis argues that there is an ethical development inherent in the mystical pedagogy of Ignatius of Loyola and Teresa of Avila. The various stages of mystical development are read through the lens of Wittgenstein as ethical forms of life premised on an absolute good. Through mystical pedagogy one simultaneously develops the language and the praxis of mystical forms of life. Mystical forms of life, though seeking the transcendent, are historically and socially conditioned. This historical and social conditioning is explored principally through Michel de Certeau’s account of spiritual spaces. ii Contents Chapter One: Introduction ......................................................................................................