Distillation of Sound: Dub in Jamaica and the Creation of Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dub Issue 15 August2017

AIRWAVES DUB GREEN FUTURES FESTIVAL RADIO + TuneIn Radio Thurs - 9-late - Cornerstone feat.Baps www.greenfuturesfestivals.org.uk/www.kingstongreenradi o.org.uk DESTINY RADIO 105.1FM www.destinyradio.uk FIRST WEDNESDAY of each month – 8-10pm – RIDDIM SHOW feat. Leo B. Strictly roots. Sat – 10-1am – Cornerstone feat.Baps Sun – 4-6pm – Sir Sambo Sound feat. King Lloyd, DJ Elvis and Jeni Dami Sun – 10-1am – DestaNation feat. Ras Hugo and Jah Sticks. Strictly roots. Wed – 10-midnight – Sir Sambo Sound NATURAL VIBEZ RADIO.COM Daddy Mark sessions Mon – 10-midnight Sun – 9-midday. Strictly roots. LOVERS ROCK RADIO.COM Mon - 10-midnight – Angela Grant aka Empress Vibez. Roots Reggae as well as lo Editorial Dub Dear Reader First comments, especially of gratitude, must go to Danny B of Soundworks and Nick Lokko of DAT Sound. First salute must go to them. When you read inside, you'll see why. May their days overflow with blessings. This will be the first issue available only online. But for those that want hard copies, contact Parchment Printers: £1 a copy! We've done well to have issued fourteen in hard copy, when you think that Fire! (of the Harlem Renaissance), Legitime Defense and Pan African were one issue publications - and Revue du Monde Noir was issued six times. We're lucky to have what they didn't have – the online link. So I salute again the support we have from Sista Mariana at Rastaites and Marco Fregnan of Reggaediscography. Another salute also to Ali Zion, for taking The Dub to Aylesbury (five venues) - and here, there and everywhere she goes. -

Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: the Helpfulness of Humorous Parody Michael Richard Lucas Clemson University

Clemson University TigerPrints All Dissertations Dissertations 5-2015 Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: The Helpfulness of Humorous Parody Michael Richard Lucas Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Lucas, Michael Richard, "Seriously Playful and Playfully Serious: The eH lpfulness of Humorous Parody" (2015). All Dissertations. 1486. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_dissertations/1486 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SERIOUSLY PLAYFUL AND PLAYFULLY SERIOUS: THE HELPFULNESS OF HUMOROUS PARODY A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Rhetorics, Communication, and Information Design by Michael Richard Lucas May 2014 Accepted by: Victor J. Vitanza, Committee Chair Stephaine Barczewski Cynthia Haynes Beth Lauritis i ABSTRACT In the following work I create and define the parameters for a specific form of humorous parody. I highlight specific problematic narrative figures that circulate the public sphere and reinforce our serious narrative expectations. However, I demonstrate how critical public pedagogies are able to disrupt these problematic narrative expectations. Humorous parodic narratives are especially equipped to help us in such situations when they work as a critical public/classroom pedagogy, a form of critical rhetoric, and a form of mass narrative therapy. These findings are supported by a rhetorical analysis of these parodic narratives, as I expand upon their ability to provide a practical model for how to create/analyze narratives both inside/outside of the classroom. -

The Lions - Jungle Struttin’ for Information and Soundclips of Our Titles, Go to Street Date: 2/19/2008

THE LIONS - JUNGLE STRUTTIN’ FOR INFORMATION AND SOUNDCLIPS OF OUR TITLES, GO TO WWW.UBIQUITYRECORDS.COM/PRESS STREET DATE: 2/19/2008 The LIONS is a unique Jamaican-inspired ------------------------------------------------------------- outfit, the result of an impromptu recording 2 x LP Price 1 x CD Price session by members of Breakestra, Connie ------------------------------------------------------------- Price and the Keystones, Rhythm Roots 01 Thin Man Skank All-Stars, Orgone, Sound Directions, Plant 02 Ethio-Steppers Life, Poetics and Macy Gray (to name a few). Gathering at Orgone's Killion Studios, in Los Angeles during the Fall of 2006, they created 03 Jungle Struttin' grooves that went beyond the Reggae spectrum by combining new and traditional rhythms, and dub mixing mastery with the global sounds of Ethiopia, Colombia and 04 Sweet Soul Music Africa. The Lions also added a healthy dose of American-style soul, jazz, and funk to create an album that’s both a nod to the funky exploits of reggae acts like Byron 05 Hot No Ho Lee and the Dragonaires and Boris Gardner, and a mash of contemporary sound stylings. 06 Cumbia Del Leon The Lions are an example of the ever-growing musical family found in Los Angeles. There is a heavyweight positive-vibe to be found in the expansive, sometimes 07 Lankershim Dub artificial, Hollywood-flavored land of Los Angeles. Many of the members of the Lions met through the LA staple rare groove outfit Breakestra and have played in 08 Tuesday Roots many projects together over the past decade. 09 Fluglin' at Dave's Reggae is a tough genre for a new ensemble act, like the Lions, to dive head-first into and pull off with unquestionable authenticity. -

The Dub June 2018

1 Spanners & Field Frequency Sound System, Reading Dub Club 12.5.18 2 Editorial Dub Front cover – Indigenous Resistance: Ethiopia Dub Journey II Dear Reader, Welcome to issue 25 for the month of Levi. This is our 3rd anniversary issue, Natty Mark founding the magazine in June 2016, launching it at the 1st Mikey Dread Festival near Witney (an event that is also 3 years old this year). This summer sees a major upsurge in events involving members of The Dub family – Natty HiFi, Jah Lambs & Lions, Makepeace Promotions, Zion Roots, Swindon Dub Club, Field Frequency Sound System, High Grade and more – hence the launch of the new Dub Diary Newsletter at sessions. The aim is to spread the word about forthcoming gigs and sessions across the region, pulling different promoters’ efforts together. Give thanks to the photographers who have allowed us to use their pictures of events this month. We welcome some new writers this month too – thanks you for stepping up Benjamin Ital and Eric Denham (whose West Indian Music Appreciation Society newsletter ran from 1966 to 1974 and then from 2014 onwards). Steve Mosco presents a major interview with U Brown from when they recorded an album together a few years ago. There is also an interview with Protoje, a conversation with Jah9 from April’s Reggae Innovations Conference, a feature on the Indigenous Resistance collective, and a feature on Augustus Pablo. Welcome to The Dub Editor – Dan-I [email protected] The Dub is available to download for free at reggaediscography.blogspot.co.uk and rastaites.com The Dub magazine is not funded and has no sponsors. -

Defining Music As an Emotional Catalyst Through a Sociological Study of Emotions, Gender and Culture

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-2011 All I Am: Defining Music as an Emotional Catalyst through a Sociological Study of Emotions, Gender and Culture Adrienne M. Trier-Bieniek Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Musicology Commons, Music Therapy Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Trier-Bieniek, Adrienne M., "All I Am: Defining Music as an Emotional Catalyst through a Sociological Study of Emotions, Gender and Culture" (2011). Dissertations. 328. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/328 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "ALL I AM": DEFINING MUSIC AS AN EMOTIONAL CATALYST THROUGH A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY OF EMOTIONS, GENDER AND CULTURE. by Adrienne M. Trier-Bieniek A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology Advisor: Angela M. Moe, Ph.D. Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 2011 "ALL I AM": DEFINING MUSIC AS AN EMOTIONAL CATALYST THROUGH A SOCIOLOGICAL STUDY OF EMOTIONS, GENDER AND CULTURE Adrienne M. Trier-Bieniek, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2011 This dissertation, '"All I Am': Defining Music as an Emotional Catalyst through a Sociological Study of Emotions, Gender and Culture", is based in the sociology of emotions, gender and culture and guided by symbolic interactionist and feminist standpoint theory. -

Collection Workmen Are Finishing the Interior Wood Drive

.. ■ ■ I"' M>/»m ^■Mi. g»«.-^«*r<iruSii>.'Ti,ir.ga;<s^:fc»'yw>rai»igre8^rrat*rt^- m tfm • S A T O & P A ^ - J A K V A S y I t . : 1 ^ 7 V t ,11 w as covarUiB the ylatt of tha Bloodmoblls at Canter Church JNew W adildl JSdiaol T b I ecr . S h a p e ABquIT qwh TTmTaffay. ' K * parked h it h«t Cars CoUide,- M unehm ee^ji d tr of VUUmm C h e a r m Heard Along Main Street and :eoat adth -the other beta and t i|ri and lira John Stanlayi Jr.« ...... ^ ... eoats ln the outer lobby and arent Four lujured of ‘AcoBdetofa, N, T., anjiounr* about his bueinesa. YOL.LXXI.mM an vago |g) NANGNB|r|SlL'CONNn BtONDAY, JANUARY 21, 1952 Uia birth of a soh, John Mark, on 4nd on Some of Manehe$ter*$ Streetsi Too When he flniahed, he came out (PDUIITBEN FAGIO) Dae. a*. Ufa. Stanluy. la the for- to find that there w ai only one Bor Helm Hohl of this town. A Flaee la H ie Sun '4Almanxc. trying to convince the hat left—and It wasn't his. But Mrs. Sara Biick, 77, b For many years now Town Clerk , editors of that publication that he took It anyway, not to be In H ospital W ith Frac* t ” " ■'* Tha Manchester Girl Scout L«a- Sam'Turlcington baa been waging this waa one town and an urban caught abort, and notified one of * iiara’ Association will »ee.t Wed- Manchester's fight for recognition town, at that. -

View Song List

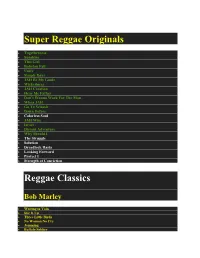

Super Reggae Originals Togetherness Sunshine This Girl Babylon Fall Unify Simple Days JAH Be My Guide Wickedness JAH Creation Hear Me Father Don’t Wanna Work For The Man Whoa JAH Go To Selassie Down Before Colorless Soul JAH Wise Israel Distant Adventure Why Should I The Struggle Solution Dreadlock Rasta Looking Forward Protect I Strength of Conviction Reggae Classics Bob Marley Waiting in Vain Stir It Up Three Little Birds No Woman No Cry Jamming Buffalo Soldier I Shot the Sherriff Mellow Mood Forever Loving JAH Lively Up Yourself Burning and Looting Hammer JAH Live Gregory Issacs Number One Tune In Night Nurse Sunday Morning Soon Forward Cool Down the Pace Dennis Brown Love and Hate Need a Little Loving Milk and Honey Run Too Tuff Revolution Midnite Ras to the Bone Jubilees of Zion Lonely Nights Rootsman Zion Pavilion Peter Tosh Legalize It Reggaemylitis Ketchie Shuby Downpressor Man Third World 96 Degrees in the Shade Roots with Quality Reggae Ambassador Riddim Haffe Rule Sugar Minott Never Give JAH Up Vanity Rough Ole Life Rub a Dub Don Carlos People Unite Credential Prophecy Civilized Burning Spear Postman Columbus Burning Reggae Culture Two Sevens Clash See Dem a Come Slice of Mt Zion Israel Vibration Same Song Rudeboy Shuffle Cool and Calm Garnet Silk Zion in a Vision It’s Growing Passing Judgment Yellowman Operation Eradication Yellow Like Cheese Alton Ellis Just A Guy Breaking Up is Hard to Do Misty in Roots Follow Fashion Poor and Needy -

Dennis Brown ARTIST: Dennis Brown TITLE: The

DATE March 27, 2003 e TO Vartan/Um Creative Services/Meire Murakami FROM Beth Stempel EXTENSION 5-6323 SUBJECT Dennis Brown COPIES Alice Bestler; Althea Ffrench; Amy Gardner; Andy McKaie; Andy Street; Anthony Hayes; Barry Korkin; Bill Levenson; Bob Croucher; Brian Alley; Bridgette Marasigan; Bruce Resnikoff; Calvin Smith; Carol Hendricks; Caroline Fisher; Cecilia Lopez; Charlie Katz; Cliff Feiman; Dana Licata; Dana Smart; Dawn Reynolds; [email protected]; Elliot Kendall; Elyssa Perez; Frank Dattoma; Frank Perez; Fumiko Wakabayashi; Giancarlo Sciama; Guillevermo Vega; Harry Weinger; Helena Riordan; Jane Komarov; Jason Pastori; Jeffrey Glixman; Jerry Stine; Jessica Connor; Jim Dobbe; JoAnn Frederick; Joe Black; John Gruhler; Jyl Forgey; Karen Sherlock; Kelly Martinez; Kerri Sullivan; Kim Henck; Kristen Burke; Laura Weigand; Lee Lodyga; Leonard Kunicki; Lori Froeling; Lorie Slater; Maggie Agard; Marcie Turner; Margaret Goldfarb; Mark Glithero; Mark Loewinger; Martin Wada; Melanie Crowe; Michael Kachko; Michelle Debique; Nancy Jangaard; Norma Wilder; Olly Lester; Patte Medina; Paul Reidy; Pete Hill; Ramon Galbert; Randy Williams; Robin Kirby; Ryan Gamsby; Ryan Null; Sarah Norris; Scott Ravine; Shelin Wing; Silvia Montello; Simon Edwards; Stacy Darrow; Stan Roche; Steve Heldt; Sujata Murthy; Todd Douglas; Todd Nakamine; Tracey Hoskin; Wendy Bolger; Wendy Tinder; Werner Wiens ARTIST: Dennis Brown TITLE: The Complete A&M Years CD #: B0000348-02 UPC #: 6 069 493 683-2 CD Logo: A&M Records & Chronicles Attached please find all necessary liner notes and credits for this package. Beth Dennis Brown – Complete A&M Years B0000348-02 1 12/01/19 11:49 AM Dennis Brown The Complete A&M Years (CD Booklet) Original liner notes from The Prophet Rides Again This album is dedicated to the Prophet Gad (Dr. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

The Record Producer As Nexus: Creative Inspiration, Technology and the Recording Industry

The Record Producer as Nexus: Creative Inspiration, Technology and the Recording Industry A submission presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Glamorgan/Prifysgol Morgannwg for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael John Gilmour Howlett April 2009 ii I certify that the work presented in this dissertation is my own, and has not been presented, or is currently submitted, in candidature for any degree at any other University: _____________________________________________________________ Michael Howlett iii The Record Producer as Nexus: Creative Inspiration, Technology and the Recording Industry Abstract What is a record producer? There is a degree of mystery and uncertainty about just what goes on behind the studio door. Some producers are seen as Svengali- like figures manipulating artists into mass consumer product. Producers are sometimes seen as mere technicians whose job is simply to set up a few microphones and press the record button. Close examination of the recording process will show how far this is from a complete picture. Artists are special—they come with an inspiration, and a talent, but also with a variety of complications, and in many ways a recording studio can seem the least likely place for creative expression and for an affective performance to happen. The task of the record producer is to engage with these artists and their songs and turn these potentials into form through the technology of the recording studio. The purpose of the exercise is to disseminate this fixed form to an imagined audience—generally in the hope that this audience will prove to be real. -

Big Youth Dread Ina Babylon / I Pray Thee Continually Mp3, Flac, Wma

Big Youth Dread Ina Babylon / I Pray Thee Continually mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Reggae Album: Dread Ina Babylon / I Pray Thee Continually Country: UK Style: Roots Reggae MP3 version RAR size: 1370 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1767 mb WMA version RAR size: 1978 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 262 Other Formats: VOC ADX WMA MP2 VQF MMF AIFF Tracklist A Dread Ina Babylon B I Pray Thee Continually Companies, etc. Published By – Negusa Nagast Credits Producer, Written-By – M. Buchanan* Notes Riddim directory: A Only A Smile B Satta (original Abyssinians/Studio One cut) Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year I Pray Thee Continually / Dread Agustus none Big Youth none Jamaica 1973 In A Babylon (7", Blu) Buchanan Dread In A Babylon / I Pray Thee Agustus none Big Youth none Jamaica 1973 Continually (7", Bro) Buchanan I Pray Thee Continually / Dread Agustus none Big Youth none Jamaica 1973 In A Babylon (7", Cap) Buchanan Dread In A Babylon / I Pray Thee Agustus none Big Youth none Jamaica 1973 Continually (7", Bla) Buchanan Related Music albums to Dread Ina Babylon / I Pray Thee Continually by Big Youth U-Roy - Dread In A Babylon Sam Bramwell - It A Go Dread Ina Babylon Big Youth With G. Isaacs - L. Sibbles - Down Town Kingston Pollution / Hot Stock Various - Freedom / The Eden / Trombone Dub / Thanks And Praises / Dread In A Babylon / Chanting Big Youth - Natty Dread She Want / A Wah The Dread Locks Want Irie Darlings & Big Youth - Beat Down Babylon Big Youth / The Groove Master - House Of Dread Lacks / Tangle Lacks Massive Dread - Massive Dread Wayne Jarrett - Satta Dread The Mighty Diamonds - Possie Are You Ready / Pray To Thee. -

Carlton Barrett

! 2/,!.$ 4$ + 6 02/3%2)%3 f $25-+)4 7 6!,5%$!4 x]Ó -* Ê " /",½-Ê--1 t 4HE7ORLDS$RUM-AGAZINE !UGUST , -Ê Ê," -/ 9 ,""6 - "*Ê/ Ê /-]Ê /Ê/ Ê-"1 -] Ê , Ê "1/Ê/ Ê - "Ê Ê ,1 i>ÌÕÀ} " Ê, 9½-#!2,4/."!22%44 / Ê-// -½,,/9$+.)"" 7 Ê /-½'),3(!2/.% - " ½-Ê0(),,)0h&)3(v&)3(%2 "Ê "1 /½-!$2)!.9/5.' *ÕÃ -ODERN$RUMMERCOM -9Ê 1 , - /Ê 6- 9Ê `ÊÕV ÊÀit Volume 36, Number 8 • Cover photo by Adrian Boot © Fifty-Six Hope Road Music, Ltd CONTENTS 30 CARLTON BARRETT 54 WILLIE STEWART The songs of Bob Marley and the Wailers spoke a passionate mes- He spent decades turning global audiences on to the sage of political and social justice in a world of grinding inequality. magic of Third World’s reggae rhythms. These days his But it took a powerful engine to deliver the message, to help peo- focus is decidedly more grassroots. But his passion is as ple to believe and find hope. That engine was the beat of the infectious as ever. drummer known to his many admirers as “Field Marshal.” 56 STEVE NISBETT 36 JAMAICAN DRUMMING He barely knew what to do with a reggae groove when he THE EVOLUTION OF A STYLE started his climb to the top of the pops with Steel Pulse. He must have been a fast learner, though, because it wouldn’t Jamaican drumming expert and 2012 MD Pro Panelist Gil be long before the man known as Grizzly would become one Sharone schools us on the history and techniques of the of British reggae’s most identifiable figures.