Working Paper Series Paper 42

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8J Electrolux

Electrolux began Australian operations in 1925 cleaners, scrubbing and, in New Zealand the following year. and poli shing Manufacturing in Australia began in 1934, in a small machines, and carpet factory in West Melbourne. The company moved washers. to South Yarra two Electro l ux years later and Professional Food remained at that site Service appliances are for almost half a used extensively in century. leading hotel a nd 8J Electrolux The Electrolux restaurant kitchens Group's 2001 across the world, inclu acquisition of Email ding the well-known Major Appliances Tetsuya's restaurant in operations included Sydney. such favoured and trusted names as RECENT THE MARKET Westinghouse, DEVELOPMENTS BRAND VALUES No market more accurately reflects our changing Kelvinator and Electrolux is now focused on rationalising its stable The Electrolux brand name gives consumers needs than that for domestic appliances. Refrige Simpson, Hoove1~ of brands and establishing Electro lux as its premier confidence in the group's products and services in rators, vacuum cleaners and lawnmowers evolve Chef and Dishlex, brand in domestic appliances around the world. In a complex, crowded world. quickly to till the demands of discerning and critical further strengthe line with this is, consumer insights gained from "Electrolux wil l be a leader in world-class homemakers. ning the company's extensive research in key international markets will products that make everyday I ife more comfmtable, The whitegoods market alone is valued at more position as the world's favourite supplier of drive Electrolux product design and development. easier and safer," says the Electrolux Mission than $2.5 billion per year in Australia and continues powered domestic and garden appliances. -

Haier Group Corporation Is a Chinese Multinational Home Appliances and Consumer Electronics Company Headquartered in Qingdao, China

Haier Group Corporation is a Chinese multinational home appliances and consumer electronics company headquartered in Qingdao, China. It designs, develops, manufactures and sells products including refrigerators, air conditioners, washing machines, microwave ovens, mobile phones, computers, and televisions. The home appliances business, namely Haier Smart Home, has seven global brands – Haier, Casarte, Leader, GE Appliances, Fisher & Paykel, Aqua and Candy. According to data released by Euromonitor,[1] Haier is the number one brand globally in major appliances for 10 consecutive years from 2009 In June 2015 Haier Group acquired General Electric's appliance division for $5.4 billion. GE Appliances is headquartered in Louisville, KY. GE Appliances is a formally American appliance manufacturer based in Louisville, Kentucky, USA. It is majority owned by Haier. It is one of the largest appliance brands in the United States and manufactures appliances under a house of brands[4] which include: GE, GE Profile, Café, Monogram, Haier and Hotpoint. Haier also owns FirstBuild, a global co-creation community and state-of-the-art micro-factory[5] on the University of Louisville's campus in Louisville, Kentucky. A second FirstBuild location is in Korea and the latest FirstBuild location is in India. The company was owned by General Electric until 2015, and was previously known as GE Appliances & Lighting and GE Consumer & Industrial. 1 • BRAINSTORMING PROTOTYPING FABRICATION ASSEMBLY • For a complete list of machines and specifications, visit the FirstBuild Microfactory Wiki. 2 3 GENERAL MOTORS – SAIC, CHINESE AUTO MAKER SAIC General Motors Corporation Limited (More commonly known as SAIC--GM; Chinese: 上汽通用汽车; formerly known as Shanghai General Motors Company Ltd, Shanghai GM; Chinese: 上海通用汽车) is a joint venture between General Motors Company and the Chinese SAIC Motor that manufactures and sells Chevrolet, Buick, and Cadillac brand automobiles in Mainland China. -

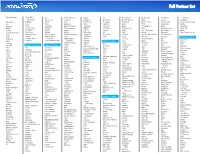

Full Partner List

Full Partner List Partnerships: Spyder Digital SIIG Franklin Electronic Solidtek SIIG BenQ America HIVI Acoustics PC Treasures Electronics) Bags & Carry Cases Research Inc. StarTech.com Gear Head Standzout StarTech.com Blue Microphones HMDX Peerless Withings Inc 3Dconnexion STM Bags Symtek Gefen StarTech.com Thermaltake BodyGuardz Honeywell Home Pentax Imaging Xavier Professional Cable Acer Symtek Targus Genius USA Targus TRENDnet Boom HP Inc. Phiaton Corp. Yamaha Adesso Inc. Targus Thermaltake Gigabyte Technology Thermaltake Turtle Beach Braven IAV Lightspeaker Philips Zagg-iFrogz AIRBAC The Joy Factory TRENDnet Griffin Technology TRENDnet U.S. Robotics BTI-Battery Tech. iHome Philips Electronics Zalman USA Aluratek Thermaltake Tripp Lite Gripcase Tripp Lite Visiontek BUQU Incipio Technologies Planar Systems zBoost American Weigh Scales Twelve South Visiontek Gyration Twelve South XFX C2G InFocus Plantronics Zmodo Technology Corp ASUS Urban Armor Gear VOXX Electronics Hawking Technologies TX Systems Zalman USA CAD Audio Innovative Office Products PNY Technologies Belkin Verbatim weBoost (Wilson HP Inc. U.S. Robotics Zotac Canon Interworks Polk Audio Data Storage Products Victorinox (Wenger) Electronics) HYPER by Sanho Verbatim Case-Mate Inwin Development Q-See BodyGuardz Aleratec Inc Zagg-iFrogz Xavier Professional Cable Corporation Viewsonic Casio IOGear QFX Canon Computers & Tablets Aluratek Incipio Technologies Visiontek Centon iON Camera Reticare inc CaseLogic Acer ASUS Computer & AV Cables Computer Accessories InFocus VisTablet -

A Great Brand Gives You Thousands of Opportunities!

A great brand gives you thousands of opportunities! www.electrolux.com/licensing If you have the PRODUCTS that people want, we have the BRANDS that people trust. Accelerate your business. • Make more money • Build on established brand equity • Expand into other product categories • Partner with one of the best worldwide companies You can accomplish all of the above. Through brand licensing we can help you maximize your business potential. What is brand licensing? The benefits A great product without a great brand leads The basic thought of brand licensing is to nowhere. But building a recognized brand use the strength from an established brand, takes a lot of time and investment. Working that already has consumer recognition together is the solution. You can be given and loyalty, instead of building an entirely the authority and opportunity to use a new brand from scratch that takes decades recognized name, already established and to create. well known. Brand licensing is a strategy to: Brand licensing is a contractual agreement • Grow in slow and/or fragmented markets permitting use of a brand with a defined • Capture new customer segments product, for a defined period of time, in • Recapture lost customers a defined territory. Through the licensing • Expand into new product categories process, the owner extends use of the and markets brand onto a variety of different products. • Capture new product price points and improve your margins Through licensing, we enable you to use one of our famous brands on your product. The result? You then select the manufacturer and A faster, more effective way to roll out a new control the process. -

Study on the Competitiveness of the EU Gas Appliances Sector

Ref. Ares(2015)2495017 - 15/06/2015 Study on the Competitiveness of the EU Gas Appliances Sector Within the Framework Contract of Sectoral Competitiveness Studies – ENTR/06/054 Final Report Client: Directorate-General Enterprise & Industry Rotterdam, 11 August 2009 Disclaimer: The views and propositions expressed herein are those of the experts and do not necessarily represent any official view of the European Commission or any other organisations mentioned in the Report ECORYS SCS Group P.O. Box 4175 3006 AD Rotterdam Watermanweg 44 3067 GG Rotterdam The Netherlands T +31 (0)10 453 88 16 F +31 (0)10 453 07 68 E [email protected] W www.ecorys.com Registration no. 24316726 ECORYS Macro & Sector Policies T +31 (0)31 (0)10 453 87 53 F +31 (0)10 452 36 60 Table of contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Objectives and policy rationale 5 3 Main findings and conclusions 7 4 The gas appliances sector 11 4.1 Introduction 11 4.2 Definition 11 4.3 Overview of sub-sectors 16 4.3.1 Heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) 16 4.3.2 Domestic appliances 18 4.3.3 Fittings 20 4.4 The application of statistics 22 4.5 Statistical approach to sector and subsectors 23 5 Key characteristics of the European gas appliances sector 29 5.1 Introduction 29 5.2 Importance of the sector 30 5.2.1 Output 30 5.2.2 Employment 31 5.2.3 Demand 32 5.3 Production, employment, demand and trade within EU 33 5.3.1 Production share EU-27 output per country 33 5.3.2 Employment 39 5.3.3 Demand by Member State 41 5.3.4 Intra EU trade in GA 41 5.4 Industry structure and size distribution -

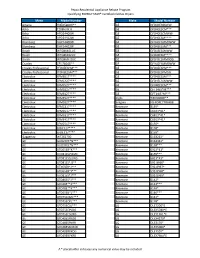

Pepco Residential Appliance Rebate Program Qualifying ENERGY STAR® Certified Clothes Dryers Make Model Number Make Model Number

Pepco Residential Appliance Rebate Program Qualifying ENERGY STAR® Certified Clothes Dryers Make Model Number Make Model Number Amana YNED5800H** GE GFD49ERSKWW Asko T208H.W.U GE GFD40ESCM*** Beko HPD24400W GE GFD40ESCMWW Beko HPD24412W GE GFD40ESM**** Blomberg DHP24400W GE GFD40ESMM0WW Blomberg DHP24412W GE GFD43ESSM*** Bosch WTG86401UC GE GFD43ESSMWW Bosch WTG86402UC GE GFD45ESM**** Bosch WTG865H2UC GE GFD45ESMM0DG Crosley CED7464G** GE GFD45ESMM0WW Crosley Professional YFD45ESPM*** GE GFD45ESPM*** Crosley Professional YFD45ESSM*** GE GFD45ESPMDG Electrolux EFME617**** GE GFD45ESSM*** Electrolux EFMC427**** GE GFD45ESSMWW Electrolux EFMC527**** GE GFV40ESCM*** Electrolux EFMC627**** GE GFT14ES*M*** Electrolux EFME427**** GE GFT14JS*M*** Electrolux EFME527**** Inglis YIED5900H** Electrolux EFME627**** Insignia NS-FDRE77WH8B Electrolux EFMC417**** Kenmore 8139* Electrolux EFMC517**** Kenmore C6163*61* Electrolux EFMC617**** Kenmore C6813*41* Electrolux EFME417**** Kenmore C6913*41* Electrolux EFME517**** Kenmore 6155* Electrolux EFDC317**** Kenmore 8158* Electrolux EFDE317**** Kenmore 8159* Gaggenau WT262700 Kenmore 6163261* GE GUD27EE*N*** Kenmore 6163361* GE GUD37EE*N*** Kenmore 8158*** GE GTD65EB*K*** Kenmore 6913*41* GE GTD81ESPJ2MC Kenmore 8159*** GE GTD81ESSJ2WS Kenmore 6813*41* GE GTD81ES*J2** Kenmore 592-8966* GE GTX65EB*J*** Kenmore 592-8967* GE GTD65EB*J*** Kenmore 592-8968* GE GTD81ES*J*** Kenmore 592-8969* GE GTD86ES*J*** Kenmore 6142* GE GFD49E**K*** Kenmore 6142*** GE GFD48E**K*** Kenmore 6146* GE GTD65EB*L*** Kenmore 6146*** -

Technology Study on Consumer Energy Devices

Department of Trade and Industry Technology Study on Consumer Energy Devices Tender Ref # DTI/RSP/RMU 10/12-13 This document contains 1. The project’s Inception Report 2. The findings from Stage 1: International Best Practice Analysis 3. The findings from Stage 2: International EE Technology Scan 4. The findings from Stage 3: Local Manufacturing Capability Scan 5. The findings from Stage 4: Local Manufacturing Transition Analysis 6. The findings from Stage 5: Recommendations and Implementation Assistance 7. Addendum TABLE OF CONTENTS Inception Report ................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Project Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Project Objectives ................................................................................................................................ 5 1.3 Project Scope........................................................................................................................................ 6 1.4 Sources of the Literary Review ............................................................................................................. 6 1.5 High Level Project Approach to Project Analysis ................................................................................. 7 1.6 Detailed Methodology of the Primary Data Collection ....................................................................... -

Fisher & Paykel Appliances Holdings Limited

FISHER & PAYKEL APPLIANCES HOLDINGS LIMITED TARGET COMPANY STATEMENT — IN RELATION TO A TAKEOVER OFFER BY HAIER NEW ZEALAND INVESTMENT HOLDING COMPANY LIMITED — 4 OCTOBER 2012 For personal use only For personal use only COVER: PHASE 7 DISHDRAWER TM DISHWASHER FISHER & PAYKEL APPLIANCES HOLDINGS LIMITED TARGET COMPANY STATEMENT CHAIRMAN’S LETTER 03 TARGET COMPANY STATEMENT (TAKEOVERS CODE DISCLOSURES) 07 SCHEDULE 1 — 4 25 For personal use only APPENDIX: INDEPENDENT ADVISER’S REPORT 37 CHAIRMAN’S LETTER For personal use only CHAIRMAN’S LETTER P3 Dear Shareholder Haier New Zealand Investment Holding Company Limited (“Haier”) has offered $1.20 per share to buy your shares in Fisher & Paykel Appliances Holdings Limited (“FPA”) by means of a formal takeover offer (the Offer“ ”). •• INDEPENDENT DIRECTORS RECOMMEND DO NOT ACCEPT HAIER’S OFFER •• The independent directors of FPA (Dr Keith Turner, Mr Philip Lough, Ms Lynley Marshall and Mr Bill Roest) (the “Independent Directors”) unanimously recommend that shareholders do not accept the Offer from Haier. In making their recommendation, the Independent Directors have carefully considered a full range of expert advice available to them. Therefore you should take no action. The principal reasons for recommending that shareholders do not accept are: _ Having regard to a full range of expert advice now available to the Independent Directors (including the Independent Adviser’s valuation range of $1.28 to $1.57 per FPA Share), the Independent Directors consider that the Offer of $1.20 per FPA Share does not adequately reflect their view of the value of FPA based on their confidence in the strategic direction of the Company; and _ FPA is in a strong financial position and, as the Independent Adviser notes, FPA is at a “relatively early stage of implementation of the company’s comprehensive rebuilding strategy”. -

Haier Electronics Group Co

Asia Pacific Equity Research 01 February 2016 Overweight Haier Electronics Group Co 1169.HK, 1169 HK Further Thoughts on Qingdao Haier/GE deal, Earnings Price: HK$13.72 ▼ Price Target: HK$18.00 Revisions, FY15 Result Preview Previous: HK$20.00 Qingdao Haier announced further details of its GE Appliances China acquisition. Key takeaways: 1) in the US, GE Appliances will continue Consumer to manage/enhance its brand position; Haier could leverage its existing Shen Li, CFA AC product portfolio to add differentiated offerings to GE's US product (852) 2800 8523 lines. 2) In the Chinese market, GE can leverage the strong distribution [email protected] channel and local expertise of Qingdao Haier to launch localised Bloomberg JPMA SHLI <GO> products. 3) Qingdao Haier currently sells through the retail channel in Ebru Sener Kurumlu (852) 2800-8521 the US, while GE has established channels across both retail and [email protected] contract channels. The Haier brand can leverage GE's existing George Hsu relationships through the US retail channel. GE also has long-term (852) 2800-8559 relationships with home owners, property developers, property [email protected] management agencies and hotel operators. The Haier brand can also Dylan Chu leverage off GE's strong position in these channels. 4) For first 20 years, (852) 2800-8537 Qingdao Haier has the global right to use GE brands and pay 0% royalty [email protected] J.P. Morgan Securities (Asia Pacific) Limited fees on both exclusive (food preparation, food preservation, household cleaning, household comfort appliances) and non-exclusive products Price Performance (water purifier products). -

Consumer Selection Guide to Refrigerators and Freezers

Virginia Cooperative Extension Service Publication No. 356-160 August 1983 Consumer Selection Guide to Refrigerators and Freezers --- - ·· -- . [ VIRGINIA TECH AND VIRGINIA STATE• VIRGINIA'S LAND GRANT UNIVERSITIES LD ~55 lt'1&~ Consumer Guide fro ~- Key facts to consider before you buy: VP/ This selection guide will help you choose the refrigerator or freezer that's right for you. If you're like most S,ec,,. consumers, you'll keep your new refrigerator or freezer for 15 years or more, so it is especially important you make the right selection. Storage Capacity torage capacity is probably the If you live alone, seldom eat at home • Do you entertain frequently? most important buying considera and about the only time you open your A Word About Outside Dimensions. tion. A "too large" n1odel refrigerator is for ice cubes or a quick S Buy a model that will fit into your snack, the smaller single-door refriger refrigerates or freezes more space than house. Be sure to measure the space ator may be the right choice for you. \'our familv needs. A "too small" available for your new refrigerator or wili' require extra trips to the ~1odel On the other hand, if you answer "yes" freezer as well as door and hallway store or filling the unit too full for to many of the following questions, clearances and compare these require adequate air circulation. In each case, you probably should consider a larger ments to the outside dimensions of the higher operating cost will result. model. model you plan to buy. Also check The capacity of a refrigerator or freezer whether your room layout requires a • Do you have a large family? is measured in cubic feet of food stor left or right-hand door. -

Paul Matters Electrical Pty Ltd

Paul Matters Electrical Pty Ltd WARRANTY LIST 11/08/17 (*) NEEDS AUTHORITY COMPANY WARRANTY PERIOD & CONDITIONS ADMIRAL SEE ELECTROLUX HOME PRODUCTS AEG SEE ELECTROLUX HOME PRODUCTS 5 Years Full Warranty Manufacturers Spare Parts Warranty – 12 months AEG VACS SEE ELECTROLUX FLOORCARE *AEG POWER TOOLS SEE TECHTRONICS 6 Years repair but only 3 Years warranty on battery/charger MUST BE REGISTERED ON LINE Manufacturers Spare Parts Warranty – 3 months AIRFLO V/C 2 Years Full Warranty Manufacturers Spare Parts Warranty – 3 months Motors – 6 months AIRFLOW C/FANS 3 Years Full Warranty Customer to call Schneider for an Authority 1300 202 525 *AIRWELL MAY BE COVERED BY SEELEY 1300 656 099 SERIAL NO. WILL DETERMINE IF IT’S COVERED NOTE: FROM 5/6/15 SEELEY ARE NO LONGER DISTRIBUTORS AMANA PARTS AVAILABLE NOW FROM CASTEL ELECTRONICS EFFECTIVE 1/9/13 AMICA NO LONGER TRADING *ANDI 3 Years Full Warranty Customer to call Andi Co for an Authority 1300 650 020 Dishwashers, Ovens, Rangehoods, Cooktops Manufacturers Spare Parts Warranty – 12 months *ANDI CO SEE GE, LEIBHERR, ANDI, FALCON & HOOVER *ANDREW BARTON SEE SPEED QUEEN COMMERCIAL CUSTOMER TO CALL 07 3712 2122 *AQUAMAX SEE RHEEM FILE *ARC APPLIANCES 2 Years Full Warranty Customer to call EDA (Home Appliances) for an Authority 1800 444 357 Manufacturers Spare Parts Warranty - 6 months *ARISIT SEE ARISTON, MIDEA, INDESIT, HUSKY, SIRIUS & TISIRA *ARISTON 2 Years Full Warranty on all appliances Customer is required to call Arisit for an Authority 1800 815 589 Manufacturers Spare Part Warranty – 12 months *ARTUSI 2 Years Full Warranty Customer to call Eurolinx for an Authority 1300 694 583 *ASAHI SEE BONN *ASKO 2 Years Full Warranty Washers, Dryers & Dishwashers 5 Years Full Warranty on all cooking appliances From November 2013 Customer to call for an Authority 1300 002 756 Manufacturers Spare Parts Warranty – 6 months *AUSTHEAT Customer to call Roband Australia for an Authority 1800 268 848 *AWA SEE HOMEMAKER, NEC, SANYO & PANASONIC MICROWAVES & WASHING MACHINES *B.A.C. -

Annual Report

Annual Report Karaağaç Caddesi No: 2-6, Sütlüce, Beyoğlu 34445 İstanbul | Türkiye Telefon: +90 212 314 34 34 Faks: +90 212 314 34 63 www.arcelikas.com /arcelikas 1 I live and prosper with my country. As long as democracy exists and thrives, so do we. We shall do our utmost to strengthen our economy. As our economy prospers, so will democracy and our standing in the world. Vehbi KOÇ 1 CONTENTS I ARÇELİK A.Ş. ANNUAL REPORT 2018 CONTENTS Sustainable Growth Corporate Responsibility Vision 2 Environmental Approach to Products and Almanac 2018 4 Production 70 Report of the Board of Directors and Message Environment-Friendly Applications 73 from the Chairman 6 Environment-Friendly Products 74 Message from the General Manager Social Responsibility Arçelik Group's vision of “Respecting The World, 8 76 Auditor’s Report on Annual Report 12 Awards and Achievements in 86 Respected Worldwide” aims to achieve profitable Financial Statement Summary 2018 16 and sustainable growth; to increase market share Financial Indicators 17 Corporate Governance Five-Year Consolidated Financial Review in its target market; the globe; to reach more 18 Shareholders 19 Corporate Governance Principles Compliance consumers in a fast-changing world with innovative Dividends Paid 20 Report 90 products and services; to safeguard the future with Share Performance 21 Statement of Compliance with Corporate corporate responsibility; and to integrate and Risk Management 22 Governance Principles 90 optimize the components of the global organization The Target Market; the Globe Global Organization while becoming a global group. Brands 28 Global Organization 118 Global Operational Network 29 Business Excellence 125 International Markets 30 Turkish Market 40 Consolidated Financial Statements and Independent Auditors’ Report Innovation Board of Directors 2018 128 Innovative and Superior Technology 48 Management 2018 130 Innovative Products 54 Independent Auditor's Report and Innovative Applications 60 Consolidated Financial Statements 139 2 3 ALMANAC 2018 I ARÇELİK A.Ş.