Archaeologies of Modern Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography Refresh March 2017

A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales Version 03, Bibliography Refresh March 2017 Medieval Bibliography of Medieval references (Wales) 2012 ‐ 2016 Adams, M., 2015 ‘A study of the magnificent remnant of a Tree Jesse at St Mary’s Priory Church, Abergavenny: Part One’, Monmouthshire Antiquary, 31, 45‐62. Adams, M., 2016 ‘A study of the magnificent remnant of a Tree Jesse at St Mary’s Priory Church, Abergavenny: Part Two, Monmouthshire Antiquary, 32, 101‐114. Allen, A. S., 2016 ‘Church Orientation in the Landscape: a perspective from Medieval Wales’, Archaeological Journal, 173, 154‐187. Austin, D., 2016 ‘Reconstructing the upland landscapes of medieval Wales’, Archaeologia Cambrensis 165, 1‐19. Baker, K., Carden, R., and Madgwick,, R. 2014 Deer and People, Windgather Press, Oxford. Barton, P. G., 2013 ‘Powis Castle Middle Park motte and bailey’, Castle Studies Group Journal, 26, 185‐9. Barton, P. G., 2013 ‘Welshpool ‘motte and bailey’, Montgomeryshire Collections 101 (2013), 151‐ 154. Barton, P.G., 2014 ‘The medieval borough of Caersws: origins and decline’. Montgomeryshire Collections 102, 103‐8. Brennan, N., 2015 “’Devoured with the sands’: a Time Team evaluation at Kenfig, Bridgend, Glamorgan”, Archaeologia Cambrensis, 164 (2015), 221‐9. Brodie, H., 2015 ‘Apsidal and D‐shaped towers of the Princes of Gwynedd’, Archaeologia Cambrensis, 164 (2015), 231‐43. Burton, J., and Stöber, K. (ed), 2013 Monastic Wales New Approaches, University of Wales Press, Cardiff Burton, J., and Stöber, K., 2015 Abbeys and Priories of Medieval Wales, University of Wales Press, Cardiff Caple, C., 2012 ‘The apotropaic symbolled threshold to Nevern Castle – Castell Nanhyfer’, Archaeological Journal, 169, 422‐52 Carr, A. -

From Time Team to Archaeology for All

From Time Team to Archaeology for All Dr Carenza Lewis University of Cambridge www.access.arch.cam.ac.uk www.access.arch.cam.ac.uk www.access.arch.cam.ac.uk Enhancing educational, economic and social well-being through active participation in archaeology. Higher Education Field Academy) Aim – To help widen participation in higher education through participation in archaeological excavation • Find out more about university • Contribute to university research • Develop confidence and deploy skills for life, learning and employment The first HEFA - Terrington 2005 “I really enjoyed it. The best bit was not knowing what we would find’ (NP) “It was hard work but I had a great time” (MS). “The kids were really enthusiastic, talking about it all the way home, asking questions…. It helps that they’re doing it themselves, not just watching” (SC) “All the students loved their experiences and are still talking about it! It was judged much ‘cooler’ than going to Alton Towers!” (EO). Coxwold Castleton Wiveton Binham Terrington St Hindringham Clement Gaywood Peakirk Acle Wisbech St Ufford Mary Castor Thorney Carleton Rode Sawtry Ramsey Isleham Garboldisham Chediston Houghton Willingham Cottenham Rampton Hessett Walberswick Riseley Swaffham Coddenham Girton Bulbeck Warnborough Great Long Sharnbrook Shelford Stapleford Bramford Shefford Melford Ashwell 2005 Pirton 2006 Manuden Thorrington Little Hallingbury 2007 West Mersea Mill Green 2008 Amwell 2009 Writtle 2010 N Daws Heath 2011 2012 0 miles 50 2013 2014 HEFA weather! WRI/13 HEFA teams, HEFA spirit -

Mick Aston Archaeology Fund Supported by Historic England and Cadw

Mick Aston Archaeology Fund Supported by Historic England and Cadw Mick Aston’s passion for involving people in archaeology is reflected in the Mick Aston Archaeology Fund. His determination to make archaeology publicly accessible was realised through his teaching, work on Time Team, and advocating community projects. The Mick Aston Archaeology Fund is therefore intended to encourage voluntary effort in making original contributions to the study and care of the historic environment. Please note that the Mick Aston Archaeology Fund is currently open to applicants carrying out work in England and Wales only. Historic Scotland run a similar scheme for projects in Scotland and details can be found at: http://www.historic-scotland.gov.uk/index/heritage/grants/grants-voluntary-sector- funding.htm. How does the Mick Aston Archaeology Fund work? Voluntary groups and societies, but also individuals, are challenged to put forward proposals for innovative projects that will say something new about the history and archaeology of local surroundings, and thus inform their future care. Proposals will be judged by a panel on their intrinsic quality, and evidence of capacity to see them through successfully. What is the Mick Aston Archaeology Fund panel looking for? First and foremost, the panel is looking for original research. Awards can be to support new work, or to support the completion of research already in progress, for example by paying for a specific piece of analysis or equipment. Projects which work with young people or encourage their participation are especially encouraged. What can funding be used for? In principle, almost anything that is directly related to the actual undertaking of a project. -

The Time Team Guide to the History of Britain Free

FREE THE TIME TEAM GUIDE TO THE HISTORY OF BRITAIN PDF Tim Taylor | 320 pages | 05 Jul 2010 | Transworld Publishers Ltd | 9781905026708 | English | London, United Kingdom The Time Team Guide to the History of Britain by Tim Taylor Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. We all know that the Battle of Hastings was fought inLondon's 'one big burning blaze' tore through the capital in and that Britain declared war on Nazi Germany inbut many of us remember the most important moments in our history by the folk stories which are attached to them. So we remember Henry VIII for his wives rather than the Reformation The Time Team Guide to the History of Britain Charles We all know that the Battle of Hastings was fought inLondon's 'one big burning blaze' tore through the capital in and that Britain declared war on Nazi Germany inbut many of us remember the most important moments in our history by the folk stories which are attached to them. But if we set aside these stories, do we really know what happened when, and why it's so important? Which came first, the Bronze Age or the Stone Age? Why did the Romans play such a significant role in our past? And how did a nation as small as Britain come to command such a vast empire? Here, Tim Taylor and the team of expert historians behind Channel 4's Time Team, answer these questions and many more, cataloguing British history in a way that is accessible to all. -

Proposed Archaeological Evaluation at Syndale Park, Ospringe, Kent

Syndale Park, Ospringe, Kent Archaeological Evaluation and an Assessment of the Results Ref: 52568.01 Wessex Archaeology May 2003 SYNDALE PARK, OSPRINGE, KENT AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION AND AN ASSESSMENT OF THE RESULTS Document Ref. 52568.01 May 2003 Prepared for: Videotext Communications Ltd 49 Goldhawk Road LONDON SW1 8QP By: Wessex Archaeology Portway House Old Sarum Park SALISBURY Wiltshire SP4 6EB © Copyright The Trust for Wessex Archaeology Limited 2003, all rights reserved The Trust for Wessex Archaeology Limited, Registered Charity No. 287786 1 SYNDALE PARK, OSPRINGE, KENT AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL EVALUATION AND AN ASSESSMENT OF THE RESULTS Contents Summary..................................................................................................................4 Acknowledgements..................................................................................................5 1 BACKGROUND............................................................................................6 1.1 Description of the site.....................................................................................6 1.2 Previous archaeological work .......................................................................6 2 METHODS.....................................................................................................8 2.1 Introduction....................................................................................................8 2.2 Aims and objectives .......................................................................................8 -

Caesar, Meet Tacitus!

New England Classical Journal Volume 43 Issue 3 Pages 167-172 8-2016 Caesar, Meet Tacitus! Katy Ganino Reddick Frank Ward Middle School Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/necj Recommended Citation Reddick, Katy Ganino (2016) "Caesar, Meet Tacitus!," New England Classical Journal: Vol. 43 : Iss. 3 , 167-172. Available at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/necj/vol43/iss3/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Classical Journal by an authorized editor of CrossWorks. RATIO ET RES New England Classical Journal 43.3 (2016) 167-172 Caesar, Meet Tacitus! Katy Ganino Reddick Frank Ward Middle School e f Our primary role as educators is to help our students make connections- between themselves and our content material, between our content material and their lives. This paper, based on a talk given at the 2015 CANE Annual Meeting, is not didactic or exhaustive. Instead it is a collection of different ways you can help your secondary students to connect to Tacitus, specifically his short work,Agricola . Many of these ideas could also apply to other authors or may inspire you in other directions; feel free to use these as a starting point to make your own connections. Although Tacitus is often perceived as a challenging author, his short work the Agricola is a wonderful companion text for Caesar’s Bellum Gallicum. As a short text it is quickly read in English and has very serviceable translations available free both online at various websites and as a Kindle download. -

IN TOUCH Issue 31 Oxford Archaeology Review 2013/14 Gill Hey Visiting OA’S Excavations on the Bexhill to Hastings Link Road MESSAGE from GILL

IN TOUCH Issue 31 Oxford Archaeology Review 2013/14 Gill Hey visiting OA’s excavations on the Bexhill to Hastings Link Road MESSAGE FROM GILL Oxford Archaeology in 2014 is an organisation looking forwards and outwards. We are delighted to be launching our new strategy to take us to 2020 (see opposite), with the ambition of being the leading heritage practice focused on delivering high-quality archaeological projects, providing good value for our clients, communicating exciting and up-to-date information to the public, and being a stimulating, safe and rewarding place to work. Our vision is to be at the forefront of advancing knowledge about the past and working in partnership with others for public benefit. A key element of the strategy is communication, both externally and internally. Since March 2007, we have produced 30 in-house magazines, one every quarter in printed and digital formats, and each packed with project news, in addition to providing information for staff on employment matters. Over time, they have become more glossy, but the challenge has been deciding what to exclude, not how to fill the space. They are We also have special features which showcase five particular a testament to the huge variety of work that has been under aspects of our work over the year: our HLF community projects; way, from strategic studies and research, through an immense National Heritage Protection Projects undertaken for English diversity of fieldwork, to news on our publications. We thought Heritage; Burials Archaeology; Industrial Archaeology; and a it was time to share this little gem with you. -

Nfl 100 All-Time Team’

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Alex Riethmiller – 310.840.4635 NFL – 11/18/19 [email protected] NFL RELEASES RUNNING BACK FINALISTS FOR THE ‘NFL 100 ALL-TIME TEAM’ 24 Transformative Rushers Kick Off Highly Anticipated Reveal The ‘NFL 100 All-Time Team’ Premieres Friday, November 22 at 8:00 PM ET on NFL Network The NFL is proud to announce the 24 running backs that have been named as finalists for the NFL 100 All-Time Team. First announced on tonight’s edition of Monday Night Countdown on ESPN, the NFL 100 All- Time Team running back finalist class account for 14 NFL MVP titles and combine for 2,246 touchdowns. Of the 24 finalists at running back, 23 are enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, OH, while one is still adding to his legacy on the field as an active player. The NFL100 All-Time Team premieres on November 22 and continues for six weeks through Week 17 of the regular season. Rich Eisen, Cris Collinsworth and Bill Belichick will reveal the NFL 100 All-Time Team selections by position in each episode beginning at 8:00 PM ET every Friday night, followed by a live reaction show hosted by Chris Rose immediately afterward, exclusively on NFL Network. Of the 24 running back finalists, Friday’s premiere of the NFL 100 All-Time Team will name 12 individuals as the greatest running backs of all time. The process to select and celebrate the historic team began in early 2018 with the selection of a 26-person blue-ribbon voting panel. -

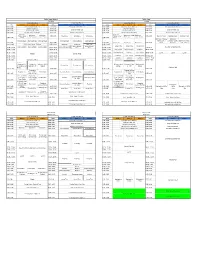

Time Team 1 Team 2 Team 3 Time Team 4 Team 5 Team 6 Time Team

Safari Camp (Week-6) Safari Camp Monday Tuesday Celebration Week Celebration Week Celebration Week Celebration Week Time Team 1 Team 2 Team 3 Time Team 4 Team 5 Team 6 Time Team 1 Team 2 Team 3 Time Team 4 Team 5 Team 6 7:00 - 8:00 Extended Care in Side Lot 7:00- 8:00 Extended Care in Side Lot 7:00 - 8:00 Extended Care in Side Lot 7:00- 8:00 Extended Care in Side Lot 8:00 - 8:40 Drop-off in Side Lot 8:00- 8:40 8:00 - 8:40 Drop-off in Side Lot 8:00- 8:40 Drop- Off in Side Lot Drop- Off in Side Lot 8:45 - 8:50 Drop-off in West Gym 8:40 - 8:50 8:45 - 8:50 Drop-off in West Gym 8:40 - 8:50 8:50 - 9:05 Opening Circle- West Gym 8:50- 9:05 Opening Circle- Side Lot 8:50 - 9:05 Opening Circle- West Gym 8:50- 9:05 Opening Circle- Side Lot Bathroom - Bathroom - Bathroom - Bathroom - Bathroom - Lobby Bathroom - Family Locker 9:05- 9:15 Attendance Attendance Attendance Family Locker 9:05- 9:15 Morning Snack Morning Snack Morning Snack Lobby Bathroom Locker Rooms Bathroom Locker Rooms 9:05 - 9:15 Room 9:05 - 9:15 Room Bathroom/ Change- Bathroom/ Morning Snack Morning Snack Morning Snack Morning Snack Morning Snack Morning Snack Family Locker Change - Lobby Bathroom/ Change - 9:15 - 9:25 9:15 - 9:45 9:15 - 9:45 Snack Time Snack Time Snack Time 9:15 - 9:45 Room Bathroom Locker Rooms 9:30 - 10:15 Whole Safari Songs- Blacktop 9:45 - 10:00 Bathroom Bathroom Bathroom 9:45 - 10:15 Bus to Ultimate Bus to Ultimate Group Time Group Time Group Time Bus to Airtastic Bus to Airtastic Bus to Airtastic Bus to Ultimate Ninja Bus Ride to Rainbow Falls 10:15 - 10:45 -

Date Day Time Team Vs Team Field Location League Winner Knox

Knox County Parks and Recreation Department Spring Adult Softball 2021 Monday Co-ed Contact the Gameline for Rain outs 215 - (GAME) 4263 or Follow Jennifer on Twitter @leftyjj 1. TN Sales *Plays on Monday's 7. Dirt Devils *All Games at the Sportspark 2. Killer B's REVISED 8. Pitches Be Crazy * Will take off May 31 Memorial3/19/2009 Day 3. BusDrivers 9. Trainwreck *1-2 Weeks of Make-ups 4. Swingers *11 Teams 10 Games 10. Creek Benders *Will play on other nights to get games in 5. Havoc 11. Sailaway Realty *Home team will be done by flip of coin by umpire 6. 640 Liquor Date Day Time Team vs Team Field Location League Winner 3/22/2021 MONDAY 8:00p.m. 3 vs 10 Field 3 SportsPark Monday Co-ed 1 has a Bye 3/22/2021 MONDAY 9:00p.m. 6 vs 7 Field 3 SportsPark Monday Co-ed 3/22/2021 MONDAY 7:00p.m. 5 vs 8 Field 4 SportsPark Monday Co-ed 3/22/2021 MONDAY 8:00p.m. 2 vs 11 Field 4 SportsPark Monday Co-ed 3/22/2021 MONDAY 9:00p.m. 4 vs 9 Field 4 SportsPark Monday Co-ed 3/29/2021 MONDAY 8:00p.m. 3 vs 9 Field 3 SportsPark Monday Co-ed 6 has a Bye 3/29/2021 MONDAY 9:00p.m. 1 vs 11 Field 3 SportsPark Monday Co-ed 3/29/2021 MONDAY 7:00p.m. 5 vs 7 Field 4 SportsPark Monday Co-ed 3/29/2021 MONDAY 8:00p.m. -

Maidstone Area Archaeological Group, Should Be Sent to Jess Obee (Address at End) Or Payments Made at One of the Meetings

Maidstone Area Archaeological Group Newsletter, March 2000 Dear Fellow Members As there is a host of announcements, I will hold over the Editorial until the next Newsletter, due in May (sighs of relief all round). David Carder Subscriptions and Membership Cards Subscriptions for the year beginning 1st April 2000 are now due. Please use the renewal form enclosed with this Newsletter, and complete as much as of it as possible - that way we can establish what members' interests really are. Return the form with your cheque by post to Jess Obee (address at end), or hand it with cheque or cash to any Committee Member who will give you a receipt. Renewing members will receive a handy Membership Card with the May Newsletter, giving details of indoor meetings, subscription rates, and contacts. In order to comply with the data protection legislation, we have included on the form a consent that your details may be held on a computer database. This data is held purely for membership administration (e.g. printing of address labels and registration of subscription payments). It will not be used for other purposes, or released to outside parties without your express consent. If you have any queries or concerns over this, please write to the Chairman. Notice of Annual General Meeting - Friday 28th April 2000 This year's AGM will be held at 7.30 pm on Friday 28th April 2000 (not 21st as previously published) at the School Hall, The Street, Detling. The Agenda is as follows : 1. Chairman's welcome 2. Apologies for absence 3. -

SAA Archaeological Record Anna Marie Prentiss (ISSN 1532-7299) Is Published five Times a Year and Is Edited by Anna Marie Prentiss

Archaeological Practice on Reality Television SOCIETY FOR AMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY the SAAarchaeologicalrecord The Magazine of the Society for American Archaeology Volume 15, No. 2 March 2015 Editor’s Corner 2 Anna Marie Prentiss From the President 3 Jeffrey H. Altschul, RPA SAA and Open Access—The Financial Implications 4 Jim Bruseth Exploring Open Access for SAA Publications 5 Sarah Whitcher Kansa and Carrie Dennett Volunteer Profile : Kirk French 9 ARCHAEOLOGICAL PRACTICE ON REALITY TELEVISION Reality Television and the Portrayal of Archaeological 10 Sarah A. Herr Practice: Challenges and Opportunities Digging for Ratings Gold: American Digger and the 12 Eduardo Pagán Challenge of Sustainability for Cable TV Interview with John Francis on National Geographic 18 Sarah A. Herr and Archaeology Programming Time Team America: Archaeology as a Gateway 21 Meg Watters to Science : Engaging and Educating the Publi c Beyond “Nectar” and “Juice” : Creating a Preservation 26 Jeffery Hanson Ethic through Reality TV Reality Television and Metal Detecting : Let’s Be Part of 30 Giovanna M. Peebles the Solution and Not Add to the Problem Metal Detecting as a Preservation and Community 35 Matthew Reeves Building Tool : Montpelier’s Metal Detecting Programs Going Around (or Beyond) Major TV : Other Media 38 Richard Pettigrew Options to Reach the Public Erratum In the Acknowledgements section of “Ho’eexokre ‘Eyookuuka’ro ‘We’re Working with Each Other”: The Pimu Catalina Island Proj - ect” Vol. 15(1):28, an important supporter was left out and should be disclosed. On the cover: Time Team America camera - Acknowledgments. The 2012 Pimu Catalina Island Archaeology man filming excavations for the episode "The Field School was also supported by the Institute for Field Research Search for Josiah Henson." Image courtesy of (IFR).