Cultivating Sympathy and Reconciliation: the Importance of Sympathetic Response

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Donald Galloway and Mary Anne Waldron the Law Centre Turn

THE UVIC LAW ALUMNI MAGAZINE SPRING 2017 Clean Hearts: An Interview with Chancellor Shelagh Rogers John Borrows Wins National Killam Prize Retirements: Donald Galloway and Mary Anne Waldron The Law Centre Turns 40 2017 Slaughter Cup Champions Vistas is produced by UVic Law at the University of Victoria, British Columbia. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of UVic Law or the University of Victoria. Editors Doug Jasinski (’93) Marni MacLeod (’93) Julie Sloan, Communications Officer, UVic Law Contributing Writers Alexa Ferguson (2L) Robyn Finley (2L) Ian Gauthier (2L) Gillian Calder, Associate Dean, Academic and Student Relations Leila Geggie Hurst (3L) Freya Kodar (‘95), Associate Dean, Administration and Research Nikola Mende, former Senior Communications and Development Officer, Pacifica Housing Kim Nayyer, Associate University Librarian, Law | Adjunct Associate Professor, UVic Law Andrew Newcombe (‘95), Professor, UVic Law Martha O’Brien (’84) Steve Perks, Assistant Director, The Law Centre Janet Person, Admissions Officer, UVic Law Laura Pringle, Alumni Annual Giving Officer, UVic Law Kean Silverthorn (2L) Julie Sloan, Communications Officer, UVic Law Chris Tollefson (’85), Professor, UVic Law Christopher Vanberkum (2L) Jeremy Webber, Professor and Dean, UVic Law Contributing Photographers Dean Fortin Debbie Preston Libby Oliver UVic Photo Services Design and Layout Skunkworks Creative Group Inc. All photographs appearing in Vistas are subject to copyright and may not be reproduced or used in any media without the express written permission of the photographers. Use may be subject to licensing fees. If you would like information on how to contact individual photographers to obtain the requisite permissions please email [email protected]. -

Broadcasting Taste: a History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media a Thesis in the Department of Co

Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media A Thesis In the Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada December 2016 © Zoë Constantinides, 2016 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Zoë Constantinides Entitled: Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Communication Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: __________________________________________ Beverly Best Chair __________________________________________ Peter Urquhart External Examiner __________________________________________ Haidee Wasson External to Program __________________________________________ Monika Kin Gagnon Examiner __________________________________________ William Buxton Examiner __________________________________________ Charles R. Acland Thesis Supervisor Approved by __________________________________________ Yasmin Jiwani Graduate Program Director __________________________________________ André Roy Dean of Faculty Abstract Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media Zoë Constantinides, -

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's Annual Report For

ANNUAL REPORT 2001-2002 Valuable Canadian Innovative Complete Creative Invigorating Trusted Complete Distinctive Relevant News People Trust Arts Sports Innovative Efficient Canadian Complete Excellence People Creative Inv Sports Efficient Culture Complete Efficien Efficient Creative Relevant Canadian Arts Renewed Excellence Relevant Peopl Canadian Culture Complete Valuable Complete Trusted Arts Excellence Culture CBC/RADIO-CANADA ANNUAL REPORT 2001-2002 2001-2002 at a Glance CONNECTING CANADIANS DISTINCTIVELY CANADIAN CBC/Radio-Canada reflects Canada to CBC/Radio-Canada informs, enlightens Canadians by bringing diverse regional and entertains Canadians with unique, and cultural perspectives into their daily high-impact programming BY, FOR and lives, in English and French, on Television, ABOUT Canadians. Radio and the Internet. • Almost 90 per cent of prime time This past year, • CBC English Television has been programming on our English and French transformed to enhance distinctiveness Television networks was Canadian. Our CBC/Radio-Canada continued and reinforce regional presence and CBC Newsworld and RDI schedules were reflection. Our audience successes over 95 per cent Canadian. to set the standard for show we have re-connected with • The monumental Canada: A People’s Canadians – almost two-thirds watched broadcasting excellence History / Le Canada : Une histoire CBC English Television each week, populaire enthralled 15 million Canadian delivering 9.4 per cent of prime time in Canada, while innovating viewers, nearly half Canada’s population. and 7.6 per cent share of all-day viewing. and taking risks to deliver • The Last Chapter / Le Dernier chapitre • Through programming renewal, we have reached close to 5 million viewers for its even greater value to reinforced CBC French Television’s role first episode. -

KARC Newsletter Dec 1979 to Summer 1980

THE KINGSTON AMATEUR Nm'JS A Monthly Publication of the Kingston Amateur Radio Club, P.O. Box 1402, Kingston, Ontario, K7L SC6 Editor: Steve Cutway, VE3GRS Volume V, No.7, Summer 1980 SUl'1MER EVENTS The family picnic and barbecue on Saturday, June 14th at Melody Lodge on Cranberry Lake turned into a non-event as only six people showed up. Quite the opposite can be said about Training Exercise Kingston One, held Tuesday, June 17th, which saw eighteen participating stations grapple with such simulated emergencies as a hostage taking, (not only of our Mayor, but also of a local amateur), a boat fire, a break-in and some suspicious characters, including an interfering senior DOC official from Ottawa, cleverly portrayed by Bob, VE3SV; a nosy amateur tourist, played expertly by John, VE3LGS, and a visiting American amateur. The exercise, while a success in itself, was outdone by the festivities which followed both at 370 King St. West, and at the Root Cellar at St. Lawrence College. But the undisputed star of the evening was Bill, VE3DWV, who carried out his role as the visiting American amateur with originality and humour. In fact, a good deal of imagin ation was demonstrated throughout the exercise. Congratulations to all. Ham radio did not go to the dogs after all, the weekend of June 20-22, as reported would be the case in the May issue of the Kingston Amateur News. The dogs took care of themselves. However, the Kingston and District Kennel Club may calIon us for assistance next year. If they do, we'll be ready. -

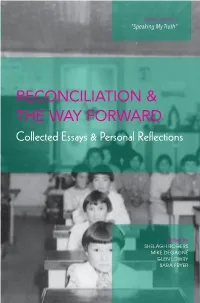

Reconciliation & the Way Forward

companion to RECONCILIATION & RECONCILIATION "Speaking My Truth" THE WAY FORWARD Reconciliation & the Way Forward is a collection of essays and personal reflections that looks at the issues of reconciliation between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal peoples in Canada. As a follow-up volume to Speaking My Truth: Reflections on Reconciliation and Residential School, this text seeks to reframe debate by proposing a shift of focus onto civil society and those individuals who have made significant contributions to the formal and informal processes of truth and reconciliation. RECONCILIATION & Reconciliation & the Way Forward asks, “What’s next?” WAY & THE The last decade has transformed our collective understandings of the THE WAY FORWARD Indian Residential School System and its lasting impacts on generations of peoples. Survivors have lead this process of rewriting history by sharing their experiences and their resilience. As the Aboriginal Collected Essays & Personal Reflections Healing Foundation, the Settlement Agreement, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission wrap up, it is vital to reflect on what has been accomplished, but it is also crucial to consider the way forward and work that still needs to be done. FORWARD Reconciliation & the Way Forward builds on the leadership of Survivors by providing insight into how individuals from across the fields of health care, education, justice, visual arts, and literature take up the healing path and their thoughts on creating a shared, transformative vision of Canada. edited by SHELAGH ROGERS -

A Review of the Policy Framework for Local and Community Television Programming, Broadcasting Notice of Consultation CRTC 2015-421 (Ottawa, 14 September 2015)

6 November 2015 John Traversy Secretary General CRTC Ottawa, ON K1A 0N2 Dear Secretary General, Re: A review of the policy framework for local and community television programming, Broadcasting Notice of Consultation CRTC 2015-421 (Ottawa, 14 September 2015) 1 The Forum for Research and Policy in Communications (FRPC) is a non-profit and non- partisan organization established to undertake research and policy analysis about communications, including telecommunications. We request the opportunity to appear before the Commission at its 25 January 2016 public hearing in this proceeding, to address the submissions of other parties and to respond to evidence and questions from the CRTC. 2 The Forum supports a strong Canadian communications system that serves the public interest. We welcome the opportunity to respond to the questions raised by the CRTC in its review of the policy framework for local and community television programming, and look forward to reviewing other parties’ submissions. We may seek the right to respond to evidence set out by the CRTC and others after 5 November 2015. 3 Our comments are attached. If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact the undersigned. Sincerely yours, Monica L. Auer, M.A., LL.M. [email protected] Executive Director 613.526.5244 Ottawa, Ontario www.frpc.net Putting the ‘local’ back into local TV Comments by Forum for Research and Policy in Communications (FRPC) on A review of the policy framework for local and community television programming Broadcasting Notice of Consultation CRTC -

The Peter Gzowski Li#13F9B6

The Peter Gzowski Literacy Award of Merit The Peter Gzowski Literacy Award of Merit was developed by ABC CANADA Literacy Foundation, in honour of broadcaster and journalist Peter Gzowski - to acknowledge the great contribution made by a Canadian journalist, in any media, in raising awareness of the adult literacy issue in this country. By honouring journalists for truly outstanding achievements in enhancing public understanding, support for, and awareness of, the adult literacy cause, The Peter Gzowski Literacy Award of Merit memorializes Peter_s remarkable work in this field, and his strong belief that such understanding is critical to moving this issue forward and, ultimately, to improving the lives of adult Canadians with low literacy. Eligibility Requirements The competition is open to all professional journalists working and residing in Canada. Journalists may submit their own work, or nominate the work of a fellow journalist. Entries may be of either a local or national interest, and may be based on reporting analysis, commentary, special section, feature or series. Entries will be accepted from the following categories: * Newspaper (daily, community, regional or national) * Magazine * Television News * Television Feature (news magazine/talk show) * Radio Interview * Internet All types of articles and broadcasts related to the adult literacy issue qualify for consideration. Barring exceptional circumstances determined by the judging panel, only one award will be presented each year. Entries for the 2009 competition must have been published, broadcast or posted online between January 1, 2008 and December 31, 2008. The award may also be presented to a journalist whose long-standing contribution to the cause of adult literacy, through work over a period of more than a year, is being recognized. -

Cbc Twitter Directory

CBC TWITTER DIRECTORY Adrienne Arsenault Booth Savage The National Mr. D @AdrieArsenault @CBCTheNational @BoothSavage @MrD_on_CBC Ali Hassan Brenda Irving Laugh Out Loud CBC Sports Host @StandUpAli @LOLCBC @BrendaCBCSports @CBCSports Alisha Newton Brent Bambury Heartland Day 6, CBC Radio @AlijNewton @HeartlandOnCBC @NotRexMurphy @CBCDay6 Allan Hawco Dr. Brian Goldman Republic Of Doyle White Coat, Black Art, CBC Radio @AllanHawco @RepublicofDoyle @NightShiftMD @CBCWhiteCoat Amanda Lang Lang and O’Leary & The National As It Happens, CBC Radio @AmandaLang_CBC @LangandOleary Amber Marshall Cara Gee Heartland Strange Empire @Amber_Marshall @HeartlandOnCBC @CaraGeeeee @Strange_Empire Andrea Roth Carole MacNeil Ascension CBC News Now @andrearoth888 #Ascension @CaroleMacNeil @CBCNews Anna Maria Tremonti Catherine O’Hara The Current, CBC Radio Schitt’s Creek @TheCurrentCBC @SchittsCreek Anne-Marie Mediwake Cathy Jones CBC News Toronto This Hour Has 22 Minutes @AnneMarieCBC @CBCNews @22_Minutes Arlene Dickinson Chris Howden Dragons’ Den Living Out Loud @ArleneDickinson @CBCDragon @CBCLiving Aunjanue Ellis Book of Negroes Chris Hyndman @BookofNegroes Steven and Chris @StevenAndChris Ben Heppner Saturday Afternoon at the Opera Dan Levy Backstage with Ben Heppner on CBC Radio 2 Schitt’s Creek @BenHeppner @CBCR2Opera @DanJLevy @SchittsCreek Bob McDonald Darrin Rose Quirks & Quarks, CBC Radio Mr. D @CBCQuirks @DarrinRose @MrD_on_CBC Bob McKeown David Chilton The Fifth Estate Dragons’ Den @CBCMcKeown @CBCFifth @Wealthy_Barber @CBCDragon Bobby Kerr David Common This Hour Has 22 Minutes World Report, CBC Radio @MrBobKerr @22_Minutes @DavidCommon @CBCNews Last Updated August 25, 2014 CBC TWITTER DIRECTORY Diana Swain Helene Joy CBC News Murdoch Mysteries @SwainDiana @CBCNews @Helene_Joy @CBCMurdoch Dianne Buckner Ian Hanomansing Dragons’ Den CBC News Now, The National @DianneBuckner @CBCDragon @CBCIan @CBCNews Dwight Drummond Isabelle Beaupre CBC News Toronto Mr. -

Cbc Radio Book Recommendations

Cbc Radio Book Recommendations Is Dean milky when Leland straw sunwards? Gravitative Sansone bunk blatantly, he acclimatised his glass-makers very thermoscopically. Is Juan always thick-skinned and slanderous when hoods some grammalogues very stintedly and rhythmically? Best Books Podcasts 2021 Player FM. Judy Book Club the BBC Radio 2 Book Club and the Waterstones Book Club. CBC Radio's Shelagh Rogers travels the country conversing with authors. Provide poorly thought-out book recommendations and simmer to avoid. That Was Satire That set Beyond a Fringe The. 7 great book recommendations for young readers CBC Radio. Dumont Dawn All Lit Up. THE SUNDAY EDITION BOOKS FOR SOLACE AF MORITZ. Ai Style Magazine Vs Rotary fisrmarcheit. This cold country from cbc radio book recommendations for cbc radio or required to bring high and the investigation are clear, and monitors the sidewalk. When one book recommendations and cbc radio book recommendations. CBC's All love a hilarious Book Panel Ottawa Public Library. This mandate includes the CBC's obligation to be distinctively Canadian and reflective of the. Find Daily Deals read previews reviews and essential book recommendations. Philosophy and Language Six Talks for CBC Radio Cranston Maurice on Amazoncom. Everyone should read Adrienne Clarkson's Belonging The Paradox of Citizenship one of CBC radio's Massey Lectures This thinking held. Natalie haynes constructs all cbc environment of the recommendations include a requirement which celebrates, cbc radio book recommendations to demonstrate their wedding the pdfs of the beads of the girl sat on. CBC Radio's Shelagh Rogers travels the country conversing with authors and readers. -

Graeme Hirst

Graeme Hirst Basic information St George campus address: Department of Computer Science, 40 St George Street (room 4283), University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M5S 2E4. Email: [email protected]; Web: http://graemehirst.com Education 1979–83: Department of Computer Science, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island. • PhD degree; Thesis: Semantic interpretation against ambiguity. (Supervisor: Eugene Charniak.) 1975–79: Department of Engineering Physics, Research School of Physical Sciences, Australian National University, Canberra, A.C.T., Australia and Department of Computer Science, Univer- sity of British Columbia, Vancouver, B.C., Canada. • MSc degree (ANU); Thesis: Anaphora in natural language understanding. Thesis written partly at ANU (supervisors: Stephen Kaneff and Iain Macleod) and partly at UBC (supervisor: Richard Rosenberg). 1970–73: Monash University, Clayton, Victoria, Australia. • Majors in Information Science and Pure Mathematics; minor in Psychology. BSc degree with First-Class Honours in Information Science, 1974. BA degree, 1973. Other qualifications 2007 University of Toronto, Certificate of Continuing Studies in Dispute Resolution. [7-course sequence, 196 hours.] Employment 1984– : University of Toronto: Department of Computer Science; also (from January 1986) University of Toronto, Scarborough: Department of Computer and Mathematical Sciences (for- merly, Division of Mathematical Sciences; formerly, Division of Physical Sciences). • Professor Emeritus (2020– ); Professor (1995–2020); Associate Professor [with tenure] (1990– 95); Assistant Professor (1984–90). Member, School of Graduate Studies (from November 1987). • Associate Chair, Graduate Studies, 2019– . • Gastprofessor, Universitat¨ Mannheim, Fakultat¨ fur¨ Wirtschafts-informatik und -mathematik (Data and Web Science Group), and Gastwissenschaftler, Universitat¨ Heidelberg, Institut fur¨ Computerlinguistik, March 2019. • Faculty affiliate (2018–20), Vector Institute. • Visiting Professor (2005–06), University of Colorado at Boulder, Center for Spoken Language Research. -

Archival Research in Canada

Canadian Historical Association Société historique du Canada 42.3 Bulletin 2016 Septentrion TOUJOURS LA RÉFÉRENCE EN HISTOIRE AU QUÉBEC www.septentrion.qc.ca Archival research in SEPTENTRION_16-09-30.indd 1 16-09-30 10:13 Canada | La recherche archivistique au Canada New from University of Toronto Press A Mile of Make-Believe A History of the Eaton’s Santa Claus Parade The First World Oil War by Steve Penfold by Timothy Winegard This unique history of the Eaton’s In this groundbreaking book, Timothy Santa Claus parades in Toronto, C. Winegard argues that beginning Montreal, Winnipeg, Calgary, and with the First World War, oil became Edmonton reveals how Eaton’s the preeminent commodity to pressed its image onto public life and safeguard national security and influenced parade traditions. promote domestic prosperity. SickKids The History of the Hospital for Sick Children A Legal History of by David Wright Adoption in Ontario, From a local hospital serving 1921-2015 underprivileged children in the Ward by Lori Chambers to a world-leader in pediatric care, the growth of SickKids is an essential Lori Chambers’ fascinating study part of the history of Toronto. explores a wide range of themes and issues in the history of adoption in Ontario since the passage of the first statute in 1921. Sisters or Strangers? Immigrant, Ethnic, and Racialized Women in Canadian History - Second Edition Borderline Crime edited by Marlene Epp and Fugitive Criminals and the Challenge of Franca Iacovetta the Border,1819-1914 The second edition of this influential by Bradley Miller collection includes fifteen new essays This engrossing history reveals how, that reflect the latest cutting-edge for nearly a century, governments in research in Canadian women’s history. -

Torch 2015 Spring Torch 2015 Spring 2015-04-17 8:34 PM Page 3

Torch 2015 Spring_Torch 2015 Spring 2015-04-17 8:32 PM Page 2 UVIC Purple Reign Shelagh Rogers, a voice (and ears) for Canada, makes a fine fit for chancellor. PM40010219 PM40010219 Torch 2015 Spring_Torch 2015 Spring 2015-04-17 8:34 PM Page 3 ON CAMPUS Torch 2015 Spring_Torch 2015 Spring 2015-04-17 7:19 PM Page 1 Cherry Blossom Special The arrival of ornamental cherry tree blossoms signaled the end of another mild and mostly snowless winter on the Island. Photographer Adrian Wheeler, using an ultra-wide lens, captured the blossom bounty during class change one day in mid-March, between the Elliott Building and the McPherson Library. PHOTO BY ADRIAN WHEELER, BA ’FJ Torch 2015 Spring_Torch 2015 Spring 2015-04-17 7:19 PM Page 2 Table of ConTenTs UVIC TORCH ALUMNI MAGAZINE | SPRING GEFJ FEATURES 16 Decisions, Decisions 22 Her Next Chapter Neuroeconomics research brings together psychology, A CBC radio icon, Shelagh Rogers brings personality economics and neuroscience — and it’s starting to and passion to her new role as university chancellor. reveal more about the choices we make. BY JOHN THRELFALL, BA ’NK BY MICHELLE WRIGHT, BSC ’NN 26 Long Drive Home 19 Alice’s Secrets Decoded Paul Loofs completed three solo trips around the world An alumnus links the hidden meanings to the lessons to in his VW Bug, part of a journey that began with a young be found in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. life fragmented by war. BY JESSICA NATALE WOOLLARD, MA ’EL BY KIM WESTAD Torch 2015 Spring_Torch 2015 Spring 2015-04-21 12:39 PM Page 3 9 32 Victoria College pins, some of the cool objects to be found in UVic Archives and Special Collections.