Anthony Munday

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

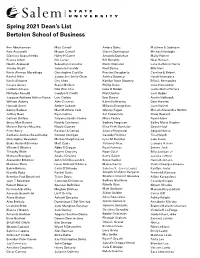

Spring 2021 Dean's List Bertolon School of Business

Spring 2021 Dean’s List Bertolon School of Business Ben Abrahamson Matt Carroll Ambra Doku Matthew S Gubitose Kyle Acciavatti Megan Carroll Gianni Dominguez Michael Hakioglu Gianluca Acquafredda Haley H Carter Amanda Donahue Molly Hamer Bianca Adam Nic Carter Bill Donalds Neal Hansen Noelle Alaboudi Sebastian Carvalho Daniel Donator Lana Kathleen Harris Jimmy Alcott Gabriela Cassidy Fiori Dorne Billy Hart Kevin Aleman Maradiaga Christopher Castillo Preston Dougherty Caroline E Hebert Rachel Allen Jacqueline Emily Chan Ashley Downey Handi Henriquez Kevin Almonte City Chen Katelyn Rose Downey Erika L Hernandez Cesare Aloise Stone M Chen Phillip Dube Julio Hernandez Luidwin Amaya Nok Wan Chu Luke D Dudek Leslie Maria Herrera Nicholas Ansaldi Carolyn R Cinelli Nick Dunfee Jack Hobbs Jayquan Anthony Arthur-Vance Lexi Ciolino Erin Dwyer Austin Holbrook William Aubrey Alex Cisneros Katie Eleftheriou Dom Hooven Hannah Aveni Amber Cokash Mikayla Evangelista Luan Horjeti Sonny Badwal Max Matthew Cole Wesley Fagan Miriam Alexandra Horton Jeffrey Baez Ryan Collins Art Fawehinmi Drew Howard Colleen Balfour Tatyana Conde-Correa Miles Feeley Ryan Huber Siena Mae Barone Nayely Contreras Sydney Ferguson Bailey Marie Hughes Melane Barrios-Macario Nicole Cooney Elise Firth-Gonzalez Geech Huot Peter Barry Rachael A Corrao Ariana Fitzgerald Abigail Hurley Zacharie Joshua Beauchamp Connor Corrigan Cassidy Fletcher Tina Huynh Christopher Beaudoin Michael Ralph Cosco Lynn M Fletcher Jake Irvine Blake Holland Benway Matt Coyle Yulianny Frias Leonora A Ivers Vikram S Bhamra Abby S Crogan Ryan Fuentes Steven Jack Timothy Blake Rupert Crossley Noor Galal Billy Jackson Jr Marissa Blonigen Anabel Cruzeta Kerry Galvin Jessica Jeffrey Alexander Bloomer John G D’Alessandro Steve Garber Hannah Jensen Madison Blum Louis Richard D’Amico Mateo Garcia Quelsi Georgia Jimenez Babin Bohara Carly D’Orlando Sabrina Y. -

I I I Vswit • I Of. All In. Imvt-Nlim:Klranli-L«Imt Itulun Hutmoovaruiuhiit Fnotl Ketort. > Royai.Bakinn F>Nwnicncn.,Ti

vSwit m •i iii ii m Mta. ' LcwIh Banden la on the alok Hal — Mr. aud: Mn.'Chaa. Brunk of Lealle :'IIni.'a«<t. Joiiaa iHOii tbe:Kalii.—Mta. vlaltud at A. Dubuta' Friday.—D«- Bobert DIH and. lira: Nathen Boae of Witt OuHola^whu' Hiaa beeu taaublng :RIvtw TutNulay.—Harrle Fox waa: lir aolionl near Parma; la homo again.— ;Batou Ranlda nn hnHlneiw laHt week. Ma«Kle Barr, who'liaa Juat returned J. N. SMITH —LuriiarJ Oawitt vli>lted hia awn In from Dakota, and Beitlia Rumory are Mills Dry fioods Company. 'jMkauii Friday.—Jamea Oardiier and vlaitlUKlii tbia vIoliilty.-Tbe anoial Wishes to call your atten- wife or nMi> Bunkerlilll vlalted M. al Jaa.llarr'a waa a aueoeaa, 810.90 be Ji Bowdlab Friday.-JaniM Naah re* ing ralaed wblcli will be uaed to get a this week to his SPECIAL Mutty hurt btahiind at Pottcr'a mill globe fur tbe aebuol. SALE of iotliatlie lalald III* fora few dava.-^ Tb« party Blveu by Irvln Hadly at VOL. XXXV.-NO. 3. Fllehbarg. MASON, MICH.. THURSDAY, JANUARY 19. 1893. WHOLE NO. 1776. Nortb I>a1lt Hotel Friday evening waa well attended. There will be an* Cliaa. Pnxann and wife are visiting WHAT IS QOINQ ON PANTS otber one there Friday aveuing, Jan. at II. R. Puxaun'a.—Meinhera nf the grange are preiiarlng a play for tbe IS. All aiecoKllallyliiviied. Supper THIS WEEK AT M. D. Q. O'S. Lard wanted at the bakery In the Warm ineala SO cents. At near future.—Tlianka totlie NBWBfor Sixty pair of $6.50 Pants roatau VUI'I* ABD VMITttBS- will beeerved at U. -

Name Date of Death Date of Paper Place of Burial

Name Date of Death Date of Paper Place of Burial Haack, Charles A. Graves 30 Nov 1907 Belvidere Cemetery Haack, Charles R. 12 Mar 1922 Haack, Edward J. 18 Nov 1938 Belvidere Haack, John 29 May 1924 Belvidere Cemetery Haack, Maria Johana Martens 23 May 1921; pg. 6 Belvidere Cemetery Haack, Theodore C. 26 Aug 1912 Belvidere Cemetery Haacker, Mrs. Anna 8 Sep 1938 Union Cemetery Haafe, William 21 Nov 1928 Kenosha, WI Haag, Jacob 20 Feb 1940 Belvidere Cemetery Haas, Edna A. 23 Sep 1981 Haas, Nancy J. 1 Jan 1996 Shirland Cemetery Haase, Dorothy D. 3 Nov 1987 Marengo City Cemetery Haase, Henry 10 Jan 1896 Haase, Nellie 10 Apr 1981 Sunset Memorial Gardens Haase, William (See: Haafe, William) Haatz, Olga 25 Jun 1930 Cherry Valley Hadebank, Ernest 6 Oct 1941 Habedank, Hanna 8 Oct 1918 15 Oct 1918 Belvidere Cemetery Habedank, Richard 23 Mar 1930 Belvidere Cemetery Habedank, Sophie 13 Jul 1942 14 Jul 1942 Habedonk, H. G. 5 Jul 1900 Indiana Haber, Joyce M. 11 Nov 2000 Dubuque, IA Haberdank, Johanna 8 Jan 1906 Belvidere Cemetery Habina, Anthony C. 22 May 1995 Hable, Edward L. 12 Sep 1988 20 Sep 1988 Sun City West, AZ Hable, Joseph A. 28 Dec 1991 Pittsville, WI Hable, Leonard F. 30 Sep 2007 St. Mary’s Cemetery Hable, Opal E. 16 Jul 1995 Hachmann, Alice M. 23 Dec 2012 RR Star 25, 26 Dec 2012 Dubuque, IA Hack, Earl R. 14 Jul 1990 Lasalle, IL Hack, baby of George 20 Jan 1903 Chicago Hackenback, Henry 29 Mar 1936 Chicago Hacker, John 7 May 1933 Marengo Cemetery Hacker, Werner H. -

The English Lyrics of the Henry VIII Manuscript

The English Lyrics of the Henry VIII Manuscript by RAYMOND G. SIEMENS B. A. (Hons), The University of Waterloo, 1989 M.A., The University of Alberta, 1991 A THESIS SUBMITTED LN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES, Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May 20, 1997 ©R.G. Siemens, 1997 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or 'by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. /7 v. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date DE-6 (2788) Abstract The Henry VIII MS (BL Additional MS 31,922)—a song book with lyrics by Henry VIII, Thomas Wyatt, William Cornish, and other literary figures of the early Henrician court—is a document that contributes greatly to a critical understanding of the connections between poetry, patronage, and power in early Renaissance society because of the prominence of its chief author, the King himself, and the manuscript's reflection of literary, social, and political elements of the early Tudor court. Acknowledging that the contents of the Henry VIII MS have been thoroughly treated as "words for music" by the musicologist John Stevens, whose Music and Poetry in the Early Tudor Court and Music at the Court of Henry VIII are the standard works in the area, my thesis builds on existing scholarship to treat the lyrics of H chiefly as "words," as literary texts. -

Chronicles of the Family Baker"

Chronicles of the Family by Lee C.Baker i ii Table of Contents 1 THE MEDIEVAL BAKERS........................................................................................1 2 THE BAKERS OF SISSINGHURST.........................................................................20 3 THE BAKERS OF LONDON AND OXFORD ............................................................49 4 THE BAKERS AT HOTHFIELD ..............................................................................58 5 COMING OUT OF ENGLAND.................................................................................70 6 THE DAYS AT MILFORD .......................................................................................85 7 EAST HAMPTON, L. I. ...........................................................................................96 8 AMAGANSETT BY THE SEA ................................................................................114 9 STATEN ISLAND AND NEW AMSTERDAM ..........................................................127 10 THE ELIZABETH TOWN PIONEERS ....................................................................138 11 THE BAKERS OF ELIZABETH TOWN AND WESTFIELD ......................................171 12 THE NEIGHBORS AT NEWARK...........................................................................198 13 THE NEIGHBORS AT RAHWAY ...........................................................................208 14 WHO IS JONATHAN BAKER?..............................................................................219 15 THE JONATHAN I. BAKER CONFUSION -

Ontario County Marriage Records 1908-1935 (Files)

Ontario County Marriage Records 1908-1935 (Files) License Groom Last Name Groom First Name Bride Last Name Bride First Name Year Number Bin ABBEY W. CHANCEY MARKS ABIGAIL A. 1909 545 AM24-019 ABBOTT MICHAEL MOSES CATHERINE 1909 347 AM24-006 ABBOTT SAMUEL JACOB SALOOM 1913 2254 AM24-032 ABBOTT STANLEY FREI EVELYN 1929 1146 AM24-073 ABEL CARL J. FREI ALBERTINA 1909 578 AM24-019 ABEL PERRY H. BAKER ETHEL M. 1912 1654 AM24-017 ABERCROMBE VAUGH F. WOODCOCK ROBY 1927 398 AM24-059 ABESHENE ARTHUR WALTERS VINA 1932 2036 AM24-088 ABRAHAM JOHN BROWN MARY 1908 52 AM24-005 ABRAHAM ALBERT A. BARRY ELIZABETH 1912 1900 AM24-018 ABRAMSKY MORRIS GRUSKIN SYLVIA 1932 4031 AM24-102 ACE ELMER GETMAN CAROL 1934 5701 AM24-130 ACHESON RALPH H. STERLING MARIE E. 1911 1306 AM24-004 ACQUILANO DOMINIC TAYLOR HELEN 1934 5596 AM24-130 ADAM GEORGE S. BLEYER JOSEPHINE A. 1909 375 AM24-006 ADAM JOHN TOWERS CARRIE 1927 543 AM24-059 ADAMS FRED PENNER NINA 1908 98 AM24-005 ADAMS FRED M. DONNELLY ETHEL M. 1912 1629 AM24-017 ADAMS MILLER BAUM ELIZABETH 1912 1687 AM24-017 ADAMS ARTHUR L. BURNETT BERTHA B. 1914 2352 AM24-032 ADAMS LESTER G. LEWIS BERTHA M. 1926 162 AM24-045 ADAMS FLOYD MARSH HELEN 1931 1820 AM24-088 ADAMS HAROLD ARGETSINGER LUCILE 1932 1992 AM24-088 ADAMS THOMAS GAUDET EMMA 1934 5597 AM24-130 ADAMSON WILLIAM GOODMAN CARRIE 1928 646 AM24-060 ADAMSON FREDERICK MELIOUS AGNES 1930 1363 AM24-074 ADSITT ARNOLD SMITH MARY 1929 1011 AM24-073 ADSITT FLOYD KEAR DOROTHY 1934 5477 AM24-116 AEBERSOLD ELMER J. -

POLITICS, SOCIETY and CIVIL WAR in WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History

Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, 162.0-1660 Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History Series editors ANTHONY FLETCHER Professor of History, University of Durham JOHN GUY Reader in British History, University of Bristol and JOHN MORRILL Lecturer in History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow and Tutor of Selwyn College This is a new series of monographs and studies covering many aspects of the history of the British Isles between the late fifteenth century and the early eighteenth century. It will include the work of established scholars and pioneering work by a new generation of scholars. It will include both reviews and revisions of major topics and books which open up new historical terrain or which reveal startling new perspectives on familiar subjects. It is envisaged that all the volumes will set detailed research into broader perspectives and the books are intended for the use of students as well as of their teachers. Titles in the series The Common Peace: Participation and the Criminal Law in Seventeenth-Century England CYNTHIA B. HERRUP Politics, Society and Civil War in Warwickshire, 1620—1660 ANN HUGHES London Crowds in the Reign of Charles II: Propaganda and Politics from the Restoration to the Exclusion Crisis TIM HARRIS Criticism and Compliment: The Politics of Literature in the Reign of Charles I KEVIN SHARPE Central Government and the Localities: Hampshire 1649-1689 ANDREW COLEBY POLITICS, SOCIETY AND CIVIL WAR IN WARWICKSHIRE, i620-1660 ANN HUGHES Lecturer in History, University of Manchester The right of the University of Cambridge to print and sell all manner of books was granted by Henry VIII in 1534. -

De Nakomelingen Van Bernhard Wibben

een genealogieonline publicatie De nakomelingen van Bernhard Wibben door Cees Eekhout 5 augustus 2021 De nakomelingen van Bernhard Wibben Cees Eekhout De nakomelingen van Bernhard Wibben Generatie 1 1. Bernhard Wibben. Hij is getrouwd met Taleke. Zij kregen 1 kind: Hermann Wibben, volg 2. Bernhard is overleden. Generatie 2 2. Hermann Wibben, zoon van Bernhard Wibben en Taleke, is geboren rond 1645 in Wahn, Germany. Hij is getrouwd op 30 oktober 1666 in Sögel, Duitsland met Hempe Manings. Zij kregen 4 kinderen: Talle Wibben, volg 3. Bernhard Wibben, volg 4. Jan Wibben, volg 5. Hermann Wibben, volg 6. Hermann is overleden. Generatie 3 3. Talle Wibben, dochter van Hermann Wibben en Hempe Manings, is geboren op 3 april 1667 in Wahn, Germany. Talle is overleden. 4. Bernhard Wibben, zoon van Hermann Wibben en Hempe Manings, is geboren op 28 februari 1669 in Wahn, Germany. Bernhard is overleden. 5. Jan Wibben, zoon van Hermann Wibben en Hempe Manings, is geboren op 26 oktober 1671 in Lohe, Graafschap Lingen, Duitsland. Hij is getrouwd met NN NN. Zij kregen 3 kinderen: Geerd Anton Wibben, volg 7. Enne Wibben, volg 8. Herman Wibben, volg 9. Jan is overleden op 37 jarige leeftijd op 13 september 1709 in Lohe, Graafschap Lingen, Duitsland. 6. Hermann Wibben, zoon van Hermann Wibben en Hempe Manings, is geboren op 28 augustus 1679 in Lohe, Graafschap Lingen, Duitsland. Hermann is overleden. https://www.genealogieonline.nl/stamboom-cees-eekhout-en-cobie-pronk/ 1 De nakomelingen van Bernhard Wibben Cees Eekhout Generatie 4 7. Geerd Anton Wibben, zoon van Jan Wibben en NN NN, is geboren op 24 november 1700 in Lohe, Graafschap Lingen, Duitsland. -

Arden of Faversham, Shakespearean Authorship, and 'The Print of Many'

Chapter 9 Arden of Faversham, Shakespearean Authorship, and 'The Print of Many' JACK ELLIOTT AND BRETT GREATLEY-HIRSCH he butchered body of Thomas Arden is found in the field behind the Abbey. After reporting Tthis discovery to Arden's wife, Franklin surveys the circumstantial evidence of footprints in the snow and blood at the scene: I fear me he was murdered in this house And carried to the fields, for from that place Backwards and forwards may you see The print of many feet within the snow. And look about this chamber where we are, And you shall find part of his guiltless blood; For in his slip-shoe did I find some rushes, Which argueth he was murdered in this room. (14.388-95) Although The Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland by Raphael Holinshed and his editors records the identities and fates of Arden's murderers in meticulous detail (Holinshed 1587, 4M4r-4M6v; 1587, 5K1v-5K3v), those responsible for composing the dramatization of this tragic episode remain unknown. We know that the bookseller Edward White entered The Lamentable and True Tragedy ofArden ofFaversham in Kent into the Stationers' Register on 3 April 1592 (Arber 1875-94, 2: 607 ), and we believe, on the basis of typographical evidence, that Edward Allde printed the playbook later that year ( STC 733). We know that Abel Jeffes also printed an illicit edition of the playbook, as outlined in disciplinary proceedings brought against him and White in a Stationers' Court record dated 18 December 1592 (Greg and Boswell 1930, 44). No copies of this pirate edition survive, but it is assumed to have merely been a reprint of White's; Jeffes was imprisoned on 7 August 1592, so his edition must have appeared prior to this date. -

Inmate Release Report Snapshot Taken: 9/28/2021 6:00:10 AM

Inmate Release Report Snapshot taken: 9/28/2021 6:00:10 AM Projected Release Date Booking No Last Name First Name 9/29/2021 6090989 ALMEDA JONATHAN 9/29/2021 6249749 CAMACHO VICTOR 9/29/2021 6224278 HARTE GREGORY 9/29/2021 6251673 PILOTIN MANUEL 9/29/2021 6185574 PURYEAR KORY 9/29/2021 6142736 REYES GERARDO 9/30/2021 5880910 ADAMS YOLANDA 9/30/2021 6250719 AREVALO JOSE 9/30/2021 6226836 CALDERON ISAIAH 9/30/2021 6059780 ESTRADA CHRISTOPHER 9/30/2021 6128887 GONZALEZ JUAN 9/30/2021 6086264 OROZCO FRANCISCO 9/30/2021 6243426 TOBIAS BENJAMIN 10/1/2021 6211938 ALAS CHRISTOPHER 10/1/2021 6085586 ALVARADO BRYANT 10/1/2021 6164249 CASTILLO LUIS 10/1/2021 6254189 CASTRO JAYCEE 10/1/2021 6221163 CUBIAS ERICK 10/1/2021 6245513 MYERS ALBERT 10/1/2021 6084670 ORTIZ MATTHEW 10/1/2021 6085145 SANCHEZ ARAFAT 10/1/2021 6241199 SANCHEZ JORGE 10/1/2021 6085431 TORRES MANLIO 10/2/2021 6250453 ALVAREZ JOHNNY 10/2/2021 6241709 ESTRADA JOSE 10/2/2021 6242141 HUFF ADAM 10/2/2021 6254134 MEJIA GERSON 10/2/2021 6242125 ROBLES GUSTAVO 10/2/2021 6250718 RODRIGUEZ RAFAEL 10/2/2021 6225488 SANCHEZ NARCISO 10/2/2021 6248409 SOLIS PAUL 10/2/2021 6218628 VALDEZ EDDIE 10/2/2021 6159119 VERNON JIMMY 10/3/2021 6212939 ADAMS LANCE 10/3/2021 6239546 BELL JACKSON 10/3/2021 6222552 BRIDGES DAVID 10/3/2021 6245307 CERVANTES FRANCISCO 10/3/2021 6252321 FARAMAZOV ARTUR 10/3/2021 6251594 GOLDEN DAMON 10/3/2021 6242465 GOSSETT KAMERA 10/3/2021 6237998 MOLINA ANTONIO 10/3/2021 6028640 MORALES CHRISTOPHER 10/3/2021 6088136 ROBINSON MARK 10/3/2021 6033818 ROJO CHRISTOPHER 10/3/2021 -

Tragic Downfall of Antony in Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra

Bilecik Şeyh Edebali Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi Makale Geliş (Submitted) Bilecik Şeyh Edebali University Journal of Social Sciences Institute Makale Kabul (Accepted) 24.08.2019 DOİ: 10.33905/bseusbed.610180 05.12.2019 Tragic Downfall of Antony in Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra Abdullah KODAL1 Abstract Although there have been lots of debates about the reason of downfall of the great Roman general Antony, there is exactly one forefront reason in his destruction, it is Cleopatra herself. Her subversive power over Antony together with her manipulative and seductive power leads to the gradual breakdown of the male protagonist Antony and his destruction at the end. Thus, to understand all aspects of his downfall as one of the triumvirs of the great Roman Empire, we have to know exactly, who Cleopatra is and the role she played in Antony’s downfall as a woman. Shakespeare’s Cleopatra even today regarded by some as the source of beauty and by some as the source of manipulation but the common point for most people; it would not be possible to describe her within the limited definitions of woman in patriarchal society and one would need more than these, at least, for Cleopatra. Regarding the different approaches and criticisms about the downfall of the protagonist Antony, my aim in this article is to show how Cleopatra as an outstanding female model in ancient ages led to the downfall of the male protagonist of Shakespeare’s play the great Roman general Antony by using her special feminine characteristic features such as her beauty, her tempting words and speeches and also her seductive wiles against patriarchal assumptions that leads her to being condemned as a femme fatale. -

Will Kemp, Shakespeare, and the Composition of Romeo and Juliet

162 Issues in Review 43 See A.J. Hoenselaars, Images of Englishmen and Foreigners in the Drama of Shake- speare and His Contemporaries: A Study in Stage Characters and National Identity in English Renaissance Drama (London and Toronto, 1992). 44 G.K. Hunter, ‘Porter, Henry (d. 1599)’, The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004) http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/22568 (accessed 21 Dec 2006). 45 Henslowe’s Diary, 63, 242–3. 46 See Hunter, ‘Porter, Henry’. 47 Lucy Munro, ‘Early Modern Drama and the Repertory Approach’, Research Oppor- tunities in Renaissance Drama 42 (2003), 1–33. Will Kemp, Shakespeare, and the Composition of Romeo and Juliet ‘Enter Will Kemp’, states Romeo and Juliet’s 1599 second quarto in its uniquely specific stage direction towards the end of scene 17.1 This uniqueness makes the quarto, which editors know as Q2, a crucially important witness to the play’s early performances, and to Kemp’s career with Shakespeare and the Lord Chamberlain’s Men. The Romeo and Juliet quartos, however, contain a number of other curious references to Kemp which act as further evidence of the working relationship between the dramatist and his company’s star clown. A comparison of the play’s two earliest quartos, Q1 of 1597 and Q2 of 1599, shows the clown role to be both malleable and formative in the work’s ongoing generic development. A study of Kemp in the play, through the textual anomalies which separate the printed quartos, thus provides a record of some of the transformations Romeo and Juliet underwent during the first years of its existence, as the company corrected, revised, abridged, and changed the scripts in order to capitalize on and contain the famous clown’s distinctive talents.