Rpos Gene Function Is a Disadvantage for Escherichia Coli BJ4 During Competitive Colonization of the Mouse Large Intestine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Albuquerque Daily Citizen, 06-12-1901 Hughes & Mccreight

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Albuquerque Citizen, 1891-1906 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 6-12-1901 Albuquerque Daily Citizen, 06-12-1901 Hughes & McCreight Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_citizen_news Recommended Citation Hughes & McCreight. "Albuquerque Daily Citizen, 06-12-1901." (1901). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/abq_citizen_news/1304 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Albuquerque Citizen, 1891-1906 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Book Binding u Blank Book Was Job Printing promptly .xteutW In oo4 laaM Ka nasi nal atyls at TMB CITIZEN Blndary. hoaldbaat TMB CTTUBN 'he Albuquerque Daily Jofe Room i item VOLUME 15. ALBUQUERQUE, NEW MEXICO, WEDNESDAY AFTERNOON, JUNE 12. 1901, NUMBER 175 states that the organisation will con- tragic death of the young New York ! stitute at least 76 well trained er, and to prove the assertion that BUTTLE UN and skilled employes, with a monthly IE DISASTER he was ahdlcted to the frlahtul tnor BIC pay roll aggregating at least 13.000. phlne habit his flesh showed that he S1KE Agents for There will be about a hundred guest naa liberally used the needle." McCALL BAZAAR MAIL ORDERS rooms, and everything will be conduct- Continuing, said the friend: PATTER MS. ed on the most Improved plan equal- knew Filled Sams the Downing family for years All Psttems 4t igc ly as nice as the finest hostelry In and did all In my power to stem the io THE InsurgentsJWere Rout- New York or any of the big eastern Many Bodies Recovered downward course AH NONE I1IOHER. -

Jconcepts BJ4 Manual

���� � �1.b�l!i I • I� U©@lr�f(ID)Wl�lfilMHliliii' 'J'NI,� _,_ 1 8oct/1n m CCfl'Wlt..- BJ4 J:l!!ATURl!B 4wd Cffill8hllf\ Ad�appercw:h Fl'0nibearll� � MPC'VD's• B481� -coi-,-�-llll-•� BJ4a.,e lll.niraJrn CQICJUIMnlB GNplilaclwaa, u., melt a,d.,,,_red: .. -· .... BJ4bo(tfwttl9J.zfon\\t'Geet Alli!wlild ml bwios �Teem�� l'1lctaylht.1!idlrd Twn llhaclla wi1h l.nllltlrim eheft8 TOOLS TOOLS NEEDED TO BUILD THIS KIT: 1. ALLEN WRENCHES 3. MISC. TOOLS ITEMS NEEDED TO COMPLETE YOUR CAR: A. .050" A. NEEDLE NOSE PLIERS 1. R/C TWO CHANNEL SURFACE FREQUENCY RADIO SYSTEM. B. 1/16" B. THREAD LOCKING COMPOUND (BLUE) 2. BATTERY PACK (6 CELL) C. 5/64" C. HOBBY KNIFE (DANGER!) THIS KNIFE CUTS 3. BATTERY CHARGER (PEAK DETECTION CHARGER) D. 3/32" PLASTIC AND FINGERS WITH EQUAL EASE. 4. ELECTRONIC SPEED CONTROL E. 2.5mm D. PRECISION RULER 5. R/C ELECTRIC MOTOR E. FLAT FILE 6. PINON GEAR (SIZE TO BE DETERMINED BY MOTOR CHOICE) F. 7/16" OPEN END WRENCH 7. 1/10TH SCALE 4WD FRONT TIRES (BOX ART SHOWN: HOLESHOTS) 2. NUT DRIVERS 8. 1/10TH SCALE BUGGY REAR TIRES (BOX ART SHOWN: HOLESHOTS) 4. HELPFUL TOOLS (NOT REQUIRED) A. 3/16" B. 1/4" A. VERNIER CALIPERS C. 11/32" B. HOBBY SCISSORS C. 2.5mm BALL END HEX DRIVER BAG A BAG "A" INCLUDES: CHASSIS x 1 TOP DECK x 1 FRONT SHOCK TOWER x 1 REAR SHOCK TOWER x 1 BEARING BLOCK x 2 STEERING RACK x 1 STEP 1 CHASSIS PREPARATION: 1. -

Lydia Tang Thesis.Pdf

THE MULTI-FACETED ARTISTRY OF VIOLIST EMANUEL VARDI BY LYDIA M. TANG THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Performance and Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Rudolf Haken, Chair Associate Professor Katherine Syer, Director of Research Associate Professor Scott Schwartz Professor Stephen Taylor Clinical Assistant Professor Elizabeth Freivogel Abstract As a pioneer viola virtuoso of the 20th century, Emanuel “Manny” Vardi (c. 1915-2011) is most widely recognized as the first violist to record all of Paganini’s Caprices. As a passionate advocate for the viola as a solo instrument, Vardi premiered and championed now-standard repertoire, elevated the technique of violists by his virtuosic example, and inspired composers to write more demanding new repertoire for the instrument. However, the details of his long and diverse career have never to date been explored in depth or in a comprehensive manner. This thesis presents the first full biographical narrative of Vardi’s life: highlighting his work with the NBC Symphony under Arturo Toscanini, his activities as a soloist for the United States Navy Band during World War II, his compositional output, visual artwork, an analysis of his playing and teaching techniques, as well as his performing and recording legacies in classical, jazz, and popular music. Appendices include a chronology of his life, discography, lists of compositions written by and for Vardi, registered copyrights, and a list of interviews conducted by the author with family members, former students, and colleagues. -

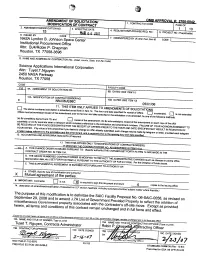

Nnj06je86c Modifications

-- MODIFICATIO , o",.,CT,OCOOE10 2. AMENDMENT/MODIFICATION NO. __ 6. iSSUED BY CODE NASA Lyndon B, Johnson Space Center InstitutJonaJProcurement Office Attn: BJ4/Robin P.Chapman Houston, TX 77058-3696 8. NAMEAND ADDRESS OF CONTRACTOR (No., street, county, State, and Zip Code) ScienceApplicationsInternationalCorporation Attn: Tuyet.T.Nguyen 2450 NASA Parkway Houston,TX 77058 CODE NO. 9B, DATEDEEITEM 11) FACILITYCODE I IOA. MODIFICATION OF CONTRACT/O'_ER NO. NNJ06JE86c 10s, DATED(SEE ITEM 13) 05/01/06 11. THIS ITEM ONLYAPPLIES TO AMENDMENTS OF SOLICITATIONS [] The abovenumberedsoJicitationis amendedas setforthin tern 14. The hour anddate specifiedfor receiptof Offers [] isextended, [] is notextended. Offersmustacknowedge receiptof thisamendmentpriortothe hourand date specifiedin thesolicitationoras amended, byone ofthe followin_lmethods: {a) By completnq Items8 and 15, and [] copiesofthe amendment;_b)By acknowledqin_lreceiptof this amendmenton each copyof the offo_" submitted;or {c) By separate letteror teleclramwhichincludesa referenceto the solicitationandamendmentnumbers. FAILUREOF YOUR ACKNOWLEDGEMENTTO BE RECEIVED AT THE PLACE DESIGNATED FOR THE RECEIPT OF OFFERS PRIOR TO THE HOUR AND DATE SPECIFIED MAY RESULT IN REJECTION OF YOUR OFFER. If byvirtue of thisamendmentyoudesireto changean offeralreadysubmitted,suchchangemay be made bytelegramor fetter,provided each telegram or letter makesreference to the solicitationandthis amendment,and is received dot to theo enin hour anddates ecifled. 12. ACCOUNTING AND APPROPRIATION DATA(If required) 13. THIS ITEM APPLIES ONLYT TO MODIFICATIONS OF CONTRACTS/ORDERS, ____ A. _ I 4 CONTRACTTHIS CHANGE ORDER ORDER NO. INIS ITEM ISSUED 10A. PURSUANT TO: {Specify authority)THE CHANGES SET FORTHIN ITEM 14 ARE MADE IN THE B. THE ABOVE NUMBERED CONTRACT/ORDER IS MODIFIED TO REFLECT THE ADMINISTRATIVECHANGES {suchas chan_esinpavin¢loffice, appropriationdate, etc.) SET FORTH IN ITEM 14, PURSUANTTO THE AUTHORITY OF FAR43,103(b). -

Bob James Three Mp3, Flac, Wma

Bob James Three mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Funk / Soul Album: Three Country: Japan Released: 1979 Style: Fusion MP3 version RAR size: 1638 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1116 mb WMA version RAR size: 1430 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 930 Other Formats: XM AAC VOC VQF DTS DMF WAV Tracklist Hide Credits One Mint Julep A1 9:04 Drums – Andy NewmarkGuitar – Jeff Mironov A2 Women Of Ireland 8:00 Westchester Lady B1 7:23 Bass – Will Lee Storm King B2 6:33 Bass – Will Lee B3 Jamaica Farewell 5:21 Companies, etc. Recorded At – Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey Credits Bass – Gary King (tracks: A1, A2, B3) Bass Trombone – Dave Taylor* Bass Trombone, Tuba – Dave Bargeron Cello – Alan Shulman, Charles McCracken Design [Album] – Rene Schumacher Drums – Harvey Mason (tracks: A2 to B3) Engineer – Rudy Van Gelder Flute – Hubert Laws, Jerry Dodgion Flute, Tenor Saxophone – Eddie Daniels Guitar – Eric Gale (tracks: A2 to B2), Hugh McCracken (tracks: A2 to B2) Harp – Gloria Agostini Keyboards – Bob James Percussion – Ralph MacDonald Photography By – Richard Alcorn Producer – Creed Taylor Tenor Saxophone, Tin Whistle – Grover Washington, Jr. Trombone – Wayne Andre Trumpet – John Frosk, Jon Faddis, Lew Soloff, Marvin Stamm Viola – Al Brown*, Manny Vardi* Violin – David Nadien, Emanuel Green, Frederick Buldrini, Harold Kohon, Harry Cykman, Lewis Eley, Matthew Raimondi, Max Ellen Notes Pressing variation with "Side 1 and 2" in upper left of labels. Bottom edge text includes "Unauthorized duplication is a violation of applicable laws". LP housed in company "CTI" sleeve. Recorded at Van Gelder Studios. ℗ 1976, Creed Taylor, Inc. -

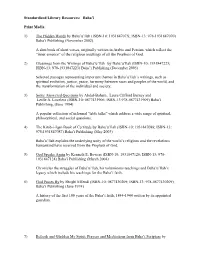

'Standardized Chapel Library Project' Lists

Standardized Library Resources: Baha’i Print Media: 1) The Hidden Words by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 193184707X; ISBN-13: 978-1931847070) Baha’i Publishing (November 2002) A slim book of short verses, originally written in Arabic and Persian, which reflect the “inner essence” of the religious teachings of all the Prophets of God. 2) Gleanings from the Writings of Baha’u’llah by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 1931847223; ISBN-13: 978-1931847223) Baha’i Publishing (December 2005) Selected passages representing important themes in Baha’u’llah’s writings, such as spiritual evolution, justice, peace, harmony between races and peoples of the world, and the transformation of the individual and society. 3) Some Answered Questions by Abdul-Baham, Laura Clifford Barney and Leslie A. Loveless (ISBN-10: 0877431906; ISBN-13 978-0877431909) Baha’i Publishing, (June 1984) A popular collection of informal “table talks” which address a wide range of spiritual, philosophical, and social questions. 4) The Kitab-i-Iqan Book of Certitude by Baha’u’llah (ISBN-10: 1931847088; ISBN-13: 978:1931847087) Baha’i Publishing (May 2003) Baha’u’llah explains the underlying unity of the world’s religions and the revelations humankind have received from the Prophets of God. 5) God Speaks Again by Kenneth E. Bowers (ISBN-10: 1931847126; ISBN-13: 978- 1931847124) Baha’i Publishing (March 2004) Chronicles the struggles of Baha’u’llah, his voluminous teachings and Baha’u’llah’s legacy which include his teachings for the Baha’i faith. 6) God Passes By by Shoghi Effendi (ISBN-10: 0877430209; ISBN-13: 978-0877430209) Baha’i Publishing (June 1974) A history of the first 100 years of the Baha’i faith, 1844-1944 written by its appointed guardian. -

Jconcepts BJ4 Worlds Edition Manual

TOOLS TOOLS NEEDED TO BUILD THIS KIT 1. ALLEN WRENCHES 3. MISC. TOOLS ITEMS NEEDED TO COMPLETE YOUR CAR: A. .050" A. NEEDLE NOSE PLIERS 1. R/C TWO CHANNEL SURFACE B. 1/16" B. THREAD LOCKING COMPOUND (BLUE) FREQUENCY RADIO SYSTEM C. 5/64" C. HOBBY KNIFE (DANGER!) THIS KNIFE CUTS 2. BATTERY PACK (6 CELL SADDLE PACK) D. 3/32" PLASTIC AND FINGERS WITH EQUAL EASE 3. BATTERY CHARGER (PEAK DETECTION) E. 2.5mm D. PRECISION RULER 4. ELECTRONIC SPEED CONTROL E. FLAT FILE 5. R/C ELECTRIC MOTOR 2. NUT DRIVERS 6. PINON GEAR (SIZE TO BE DETERMINED 4. HELPFUL TOOLS (NOT REQUIRED) BY MOTOR CHOICE) A. 3/16" 7. 1/10TH SCALE 4WD FRONT TIRES B. 1/4" A. VERNIER CALIPERS (BOX ART SHOWN: BLOCKHEAD) C. 11/32" B. HOBBY SCISSORS 8. 1/10TH SCALE BUGGY REAR TIRES C. 2.5mm BALL END HEX DRIVER (BOX ART SHOWN: X-2000) BAG A CHASSIS COMPONENTS FRONT SHOCK STEERING RACK BATTERY TRAY TOWER x 1 x 1 x 2 CHASSIS TOP DECK x 1 REAR SHOCK BEARING BLOCK BATTERY STRAP x 1 (2 PIECES) TOWER x 1 x 2 x 2 STEP 1 CHASSIS PREPARATION: FIGURE 1 1. FILE REAR TRANSMISSION SLOT WITH THE BOTTOM SURFACE OF THE FILE. FILE FILE AT THE GREATEST ANGLE POSSIBLE WITHOUT THE TOP SURFACE OF THE FILE HITTING THE OTHER SIDE OF THE SLOT. SEE FIGURE 1. 2. REFER TO FIGURE 2 FOR COMPLETED COMPARISON. NOTE CHASSIS FIGURE 2 ORIENTATION NOTE: THIS IS A CLEARANCE FOR THE BOTTOM OF THE REAR TRANSMISSION CASE. -

'Plcmilomd SERVICE the Accident but the Dieeel Unit “Don’T Say the Bishop Is Aa Black ’H Roll Singer Chuck Berry

- ' r FRIDAY, '^ARO T 11, IMO The Weather PACnS SlXTEfiH illatt rhpatPt lEttPtting Average Daily Net R ob ForeeiMl of U. B. Wm Umt B nrw i For the Week Eaded March 5th, IMO Continned fair aad eold toadidri Tho ' we-Two Group of Concor Raccoon and.tomorrow. Low'tealgM dia tiitheran Church .will, bowl 13,082 ^About Town tomorrow at 7 p.m. at the West High Snuday In low Ms. Side Rec. After bowling. Mr. From Rabiei^ MOISTENjniEAlR Menher of the Audit and Mrs. Charles Brendel ,wlU Bureau o f drenlotion. Manchester— A City o f VillageJ^arm Bow«ra PTA wUr nOMt Monday perve refrmhmentd at, the church. at t p.n»i la » • Whool auditorium. A Mck raccoon, picked up by PRICE FIVE CENTS Ttia procrkm, to b« p w « n ^ tV. Dog Warden Lebro Fracchla and’ YOU BREATHE (Ctabslfled AdverUsUig on Page 8) ^ gmtaa, Cub Scouts, Boy Scouts A hew 50-star Amerloah,;aag Patrolman Allan kmltb on Adanut (TEN PAGES-TV SECTION-SUBURBIA TODAY) MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAyMARCH 12, 1960 Girt Scouts, has been coordi- was presented yesterdgy *^*5' St. Wednesday, was not afflicted ' . w/f/t a new VOL. LXXIX, NO. 1S8 ' by Mr. and Mrs. Oeorje noon at Hollister SU Schwl to with rabies, Fracchla said today WallB^xprogtem co-chairman. Be- Girl Scout Troop 14 .at j w The taboratory division of the f t e a h m ^ wHl be aerv^ in the Juliette LovT criebratlon. The State Health Department notified 2 J 0 0 ,0 0 0 Man Ceiling fcafeteria^M rs. -

The Olga Hirsch Collection of Decorated Papers

THE OLGA HIRSCH COLLECTION OF DECORATED PAPERS MIRJAM M. FOOT l\ H>()S Mrs. Olga I lirsch, the widow of Paul Hirsch the celebrated music collector, bequeathed to the British Library her collection of decorated papers, consisting of over ;,.5oo sheets ot paper and abi)ut 130 books in paper wrappers or with decorated end- papers, as well as her eminently useful small reference library on paper making and paper decorating. After her marriage in igi i, Olga Hirsch, nee Ladenburg, started to learn bookbinding in order to be able to give the necessary professional attention to the repair of her husband's music librar\. She was trained at the Huchbinderei Ludwig in Frankfurt am Main, and started her trul\ remarkable collection from the need to match the paper for the end-leaves and wrappers of man\ ofthe music books. She also collected bookbindings and owned several Italian, French, and German Renaissance bindings, such as one with Grimaldi's Apollo and Pegasus device,^ a nice binding b\ Claude dc Picques,- the 1544 Lyons New Testament bound by Wotton's binder (. for presentation by Theoderic von Thungen to Richard von der Kher,^and the unusual and la\ishl\ tooled round binding by Caspar Meuser which was lot 336 in the \bbe\ sale ol 22 June rgO5/Her seventeenth-and eighteenth-century examples included bindings with the arms and c> phers of Louis XIII, XIV, and XV, an English Restoration binding on a 1(141 Prayer-book, and bindings with tickets of Padeloup and Derome le leune.^ This collection was dispersed after the Hirschs's arrival in England in 1936. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 9219046 Perceived structure of the environmental/conservation organization market Wright, Pamela A., Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1992 UMI 300 N. -

Music Education Resources in the CMC

Music Education Resources in the CMC Title Author or Publisher Call Number Material Type Today's Music: Good or Bad Parolini, Stephen 268.433 P257T Activity Book Finger Plays for Nursery and Kindergarten Poulsson, Emilie 372.21 P875F Activity Book Galaxy of Games for the Music Class, A Athey, Margaret 372.87 A867G Activity Book Complete Handbook of Music Games and Activities for Early Childhood Athey, Margaret 372.87 A869C Activity Book Sticks and Stones: A Classroom Music Project for Young Children and Audience Chatterly, Albert 372.87 C495S Activity Book Rhythmic Activities Clark, Carol 372.87 C592R Activity Book Get in the Groove: Discovering Jazz Using Orff and Classroom Instruments Dirksing, Donna 372.87 D599G Activity Book Movement to Music in Confined Spaces (has accompanying CDs) Froseth, James O. 372.87 F938M Activity Book Songs in Action Gelineau, R. Phyllis 372.87 G317S Activity Book Rhythm Stick Activities Glass, Henry 372.87 G549R Activity Book Let's Learn Music Hascall, Adelaide A. 372.87 H344L Activity Book Music and Instruments for Children to Make Hawkinson, John 372.87 H394M Activity Book Music Smart! (Teaching Music Appreciation) Hotchkiss, Gwen 372.87 H832M Activity Book Music Guide to Classroom Use in Intermediate Grades Leon, Ruth 372.87 L579M Activity Book Lessons in American Music Lindsay, Debra Kay Robinson 372.87 L748L Activity Book We All Go Together Lipman, Doug 372.87 L764W Activity Book One, Two, Three - Echo Me! Mitchell, Loretta 372.87 M681O Activity Book NOTE: Suggested Activities to Motivate the Teaching of Elementary Music Moore, Karen 372.87 M822N Activity Book Big Book of Music Games, The Pressnall, Debra Olson 372.87 P935B Activity Book Strategies for Teaching Prekindergarten Music MENC 372.87 S614S Activity Book Joy of Learning through Music and Movement Improvisations Stecher, Miriam B. -

Filer Code List Sorted by Filer Name

Entry Filer Code List by Filer Name 19 CFR 142.3a(c) U.S. Customs and Border Protection FILER-CODE FILER-NAME 8NJ 1 CLICK CUSTOMS INCORPORATED QE6 123 DISTRIBUTORS TZ1 138 INTERNATIONAL, INC. 92K 24/7 CUSTOMS INC. BGM 2ND EDISON INC. 8GV 361 USA INC BT1 3D INDUSTRIES INC. MMM 3M COMPANY 83Q 3P CUSTOMS CONSULTANTS, L.L.C. EFM 3V INC. KQ3 3V, INC. 8HY 4M WORLD BROKERS, INC. EUB 5.11, INC. EVM 5K LOGISTICS, INC. 97E 721 LOGISTICS LLC 8E6 88 SPIRITS CORPORATION 8FM A & A CUSTOMS BROKERAGE INC WFE A & A INTERNATIONAL SERVICES, INC. 038 A & A, LTD. MD1 A & B IMPORT EXPORT INC EFD A & B WIPER SUPPLY, INC. EH2 A & C IMPORT EXPORT SERVICES, INC. STS A & C INTERNATIONAL LOGISTICS, LLC MW6 A & D BROKERAGE INC. F31 A & F INTL 8YW A & L CUSTOMS BROKERAGE LLC 722 A & M CUSTOMS BROKERS CO ADJ A & S ENTERPRISES LLC 498 A ALEXANDER LUCIOS 9HT A AUDIO 9X6 A BROKERAGE FIRM MH9 A CUSTOMS BROKERAGE, INC. 844 A J ELLIOT CO 504 A J MURRAY & CO INC J02 A K MEADOWS 416 A L FASE & CO BW0 A MICHAEL GRAY 551 A N DERINGER, INC. R52 A O SMITH CORP T37 A SCOTT BROADHURST PA7 A T & T INC B9T A&A ACTION CUSTOMS BROKERAGE, LLC SQ4 A&A CONTRACT CUSTOMS BROKERS USA 146 A&J CUSTOMS BROKERS, INC. 817 A. VILLARREAL M32 A. ZERTUCHE, JR., CHB 993 A.A. CUSTOMS BROKER INC WHA A.B.I. FILER-CODE FILER-NAME AXB A.B.S.