Please Return Corrections Within 5 Days of Receipt to Judith Forshaw Via Email

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constitutional Authority and Its Limitations: the Politics of Sexuality in South Africa

South Africa Constitutional Authority and its Limitations: The Politics of Sexuality in South Africa Belinda Beresford Helen Schneider Robert Sember Vagner Almeida “While the newly enfranchised have much to gain by supporting their government, they also have much to lose.” Adebe Zegeye (2001) A history of the future: Constitutional rights South Africa’s Constitutional Court is housed in an architecturally innovative complex on Constitution Hill, a 100-acre site in central Johannesburg. The site is adjacent to Hillbrow, a neighborhood of high-rise apartment buildings into which are crowded thousands of mi- grants from across the country and the continent. This is one of the country’s most densely populated, cosmopolitan and severely blighted urban areas. From its position atop Constitu- tion Hill, the Court offers views of Hillbrow’s high-rises and the distant northern suburbs where the established white elite and increasing numbers of newly affluent non-white South Africans live. Thus, while the light-filled, colorful and contemporary Constitutional Court buildings reflect the progressive and optimistic vision of post-apartheid South Africa the lo- cation is a reminder of the deeply entrenched inequalities that continue to define the rights of the majority of people in the country and the continent. CONSTITUTIONAL AUTHORITY AND ITS LIMITATIONS: THE POLITICS OF SEXUALITY IN SOUTH AFRICA 197 From the late 1800s to 1983 Constitution Hill was the location of Johannesburg’s central prison, the remains of which now lie in the shadow of the new court buildings. Former prison buildings include a fort built by the Boers (descendents of Dutch settlers) in the late 1800s to defend themselves against the thousands of men and women who arrived following the discovery of the area’s expansive gold deposits. -

Appointments to South Africa's Constitutional Court Since 1994

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 15 July 2015 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Johnson, Rachel E. (2014) 'Women as a sign of the new? Appointments to the South Africa's Constitutional Court since 1994.', Politics gender., 10 (4). pp. 595-621. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X14000439 Publisher's copyright statement: c Copyright The Women and Politics Research Section of the American 2014. This paper has been published in a revised form, subsequent to editorial input by Cambridge University Press in 'Politics gender' (10: 4 (2014) 595-621) http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayJournal?jid=PAG Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Rachel E. Johnson, Politics & Gender, Vol. 10, Issue 4 (2014), pp 595-621. Women as a Sign of the New? Appointments to South Africa’s Constitutional Court since 1994. -

Faculty of Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University: Training Doctors from and for Rural South African Communities

Original Scientific Articles Medical Education Faculty of Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University: Training Doctors from and for Rural South African Communities Jehu E. Iputo, MBChB, PhD ABSTRACT Outcomes To date, 745 doctors (72% black Africans) have graduated Introduction The South African health system has disturbing in- from the program, and 511 students (83% black Africans) are currently equalities, namely few black doctors, a wide divide between urban enrolled. After the PBL/CBE curriculum was adopted, the attrition rate and rural sectors, and also between private and public services. Most for black students dropped from 23% to <10%. The progression rate medical training programs in the country consider only applicants with rose from 67% to >80%, and the proportion of students graduating higher-grade preparation in mathematics and physical science, while within the minimum period rose from 55% to >70%. Many graduates most secondary schools in black communities have limited capacity are still completing internships or post-graduate training, but prelimi- to teach these subjects and offer them at standard grade level. The nary research shows that 36% percent of graduates practice in small Faculty of Health Sciences at Walter Sisulu University (WSU) was towns and rural settings. Further research is underway to evaluate established in 1985 to help address these inequities and to produce the impact of their training on health services in rural Eastern Cape physicians capable of providing quality health care in rural South Af- Province and elsewhere in South Africa. rican communities. Conclusions The WSU program increased access to medical edu- Intervention Access to the physician training program was broad- cation for black students who lacked opportunities to take advanced ened by admitting students who obtained at least Grade C (60%) in math and science courses prior to enrolling in medical school. -

Download 2014 Annual Report

Faculty of Law 2014 Centre for ANNUAL Faculty of Law Human Rights REPORT 2 The Centre for Human Rights, based at the Faculty of Law, CONTENTS University of Pretoria, is both an academic department and a non- DIRECTOR’S MESSAGE 4 governmental organisation. ACADEMIC PROGRAMMES 6 The Centre was established in the Faculty of Law, University of Pretoria, in 1986, as part of domestic efforts against the apartheid system of the time. RESEARCH 8 The Centre for Human Rights works towards human rights education in Africa, a greater awareness of human rights, the wide dissemination of publications on human rights in Africa, and the improvement of the PROJECTS 10 rights of women, people living with HIV, indigenous peoples, sexual minorities and other disadvantaged or marginalised persons or groups across the continent. PUBLICATIONS 31 Over the years, the Centre has positioned itself in an unmatched network of practising and academic lawyers, national and international civil servants and human rights practitioners across the entire continent, with a CENTRE PERSONNEL 33 specific focus on human rights law in Africa, and international development law in general. Today, a wide network of Centre alumni contribute in numerous ways to the advancement and strengthening STAFF ACTIVITES 36 of human rights and democracy all over the Africa continent, and even further afield. FUNDING 40 In 2006, the Centre for Human Rights was awarded the UNESCO Prize for Human Rights Education, with particular recognition for the African Human Rights Moot Court Competition and the LLM in Human Rights and Democratisation in Africa. In 2012, the Centre for Human Rights was awarded the 2012 African Union Human Rights Prize. -

Walter Sisulu University

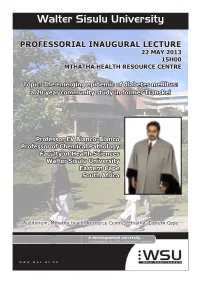

Walter Sisulu University PROFESSORIAL INAUGURAL LECTURE 22 MAY 2013 15H00 MTHATHA HEALTH RESOURCE CENTRE Topic: The emerging epidemic of diabetes mellitus: a 20 year community study in former Transkei Professor EV Blanco-Blanco Professor of Chemical Pathology Faculty of Health Sciences Walter Sisulu University Eastern Cape South Africa Auditorium, Mthatha Health Resource Centre, Mthatha, Eastern Cape www.wsu.ac.za WALTER SISULU UNIVERSITY (WSU) DEPARTMENT OF CHEMICAL PATHOLOGY SCHOOL OF MEDICINE FACULTY OF HEALTH SCIENCES TOPIC “THE EMERGING EPIDEMIC OF DIABETES MELLITUS: A 20-YEAR COMMUNITY STUDY IN THE FORMER TRANSKEI” BY ERNESTO V. BLANCO-BLANCO PROFESSOR OF CHEMICAL PATHOLOGY DATE: 22 MAY 2013 VENUE: UMTATA HEALTH RESOURCE CENTRE 3 4 INTRODUCTION AND TOPIC MOTIVATION DIABETES MELLITUS Definition Historical background CLASSIFICATION OF DIABETES MELLITUS DIAGNOSIS OF DIABETES MELLITUS RISK FACTORS AND PREDISPOSING CONDITIONS FOR DIABETES COMPLICATIONS OF DIABETES MELLITUS THE GLOBAL PREVALENCE & GLOBAL BURDEN OF DIABETES THE AFRICAN BURDEN OF DIABETES MELLITUS THE SOUTH AFRICAN BURDEN OF DIABETES MELLITUS CONSEQUENCES OF THE BURDEN OF DIABETES IMPLICATIONS OF THE BURDEN OF DIABETES FOR HEALTH PLANNING DIABETES PREVENTION AS STRATEGY CONTROL OF THE CURRENT BURDEN OF DIABETES CONCLUSIONS REFERENCES 5 INTRODUCTION AND TOPIC MOTIVATION Chemical Pathology, Diabetes Mellitus and the Former Transkei I am a Chemical Pathologist by training. The term ‘pathology’ derives from the Greek words “pathos” meaning “disease” and “logos” meaning “a treatise”. Pathology is a major field of Medicine that deals with the essential nature of diseases, their processes and consequences. A medical doctor that specializes in pathology is known as ‘a pathologist’. Chemical Pathology is that branch of Pathology, which deals specially with the biochemical basis of diseases and the use of biochemical tests carried out at hospital laboratories on the blood and other body fluids to provide support to clinicians. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Inkanyiso OFC 8.1 FM.Fm

21 The suppression of political opposition and the extent of violating civil liberties in the erstwhile Ciskei and Transkei bantustans, 1960-1989 Maxwell Z. Shamase 1 Department of History, University of Zululand [email protected] This paper aims at interrogating the nature of political suppression and the extent to which civil liberties were violated in the erstwhile Ciskei and Transkei. Whatever the South African government's reasons, publicly stated or hidden, for encouraging bantustan independence, by the time of Ciskei's independence ceremonies in December 1981 it was clear that the bantustans were also to be used as a more brutal instrument for suppressing opposition. Both Transkei and Ciskei used additional emergency-style laws to silence opposition in the run-up to both self- government and later independence. By the mid-1980s a clear pattern of brutal suppression of opposition had emerged in both bantustans, with South Africa frequently washing its hands of the situation on the grounds that these were 'independent' countries. Both bantustans borrowed repressive South African legislation initially and, in addition, backed this up with emergency-style regulations passed with South African assistance before independence (Proclamation 400 and 413 in Transkei which operated from 1960 until 1977, and Proclamation R252 in Ciskei which operated from 1977 until 1982). The emergency Proclamations 400, 413 and R252 appear to have been retained in the Transkei case and introduced in the Ciskei in order to suppress legal opposition at the time of attainment of self-government status. Police in the bantustans (initially SAP and later the Transkei and Ciskei Police) targeted political opponents rather than criminals, as the SAP did in South Africa. -

Unrevised Hansard National

UNREVISED HANSARD NATIONAL ASSEMBLY TUESDAY, 13 JUNE 2017 Page: 1 TUESDAY, 13 JUNE 2017 ____ PROCEEDINGS OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY ____ The House met at 14:02. The Speaker took the Chair and requested members to observe a moment of silence for prayer or meditation. MOTION OF CONDOLENCE (The late Ahmed Mohamed Kathrada) The CHIEF WHIP OF THE MAJORITY PARTY: Hon Speaker I move the Draft Resolution printed in my name on the Oder Paper as follows: That the House — UNREVISED HANSARD NATIONAL ASSEMBLY TUESDAY, 13 JUNE 2017 Page: 2 (1) notes with sadness the passing of Isithwalandwe Ahmed Mohamed Kathrada on 28 March 2017, known as uncle Kathy, following a short period of illness; (2) further notes that Uncle Kathy became politically conscious when he was 17 years old and participated in the Passive Resistance Campaign of the South African Indian Congress; and that he was later arrested; (3) remembers that in the 1940‘s, his political activities against the apartheid regime intensified, culminating in his banning in 1954; (4) further remembers that in 1956, our leader, Kathrada was amongst the 156 Treason Trialists together with Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu, who were later acquitted; (5) understands that he was banned and placed under a number of house arrests, after which he joined the political underground to continue his political work; UNREVISED HANSARD NATIONAL ASSEMBLY TUESDAY, 13 JUNE 2017 Page: 3 (6) further understands that he was also one of the eight Rivonia Trialists of 1963, after being arrested in a police swoop of the Liliesleaf -

Top Court Trims Executive Power Over Hawks

Legalbrief | your legal news hub Sunday 26 September 2021 Top court trims executive power over Hawks The Constitutional Court has not only agreed that legislation governing the Hawks does not provide adequate independence for the corruption-busting unit, it has 'deleted' the defective sections, notes Legalbrief. It found parts of the legislation that governs the specialist corruption-busting body unconstitutional, because they did not sufficiently insulate it from potential executive interference. This, notes a Business Day report, is the second time the court has found the legislation governing the Hawks, which replaced the Scorpions, unconstitutional for not being independent enough. The first time, the court sent it back to Parliament to fix. This time the court did the fixing, by cutting out the offending words and sections. The report says the idea behind the surgery on the South African Police Service (SAPS) Act was to ensure it had sufficient structural and operational independence, a constitutional requirement. In a majority judgment, Chief Justice Mogoeng Mogoeng said: 'Our anti-corruption agency is not required to be absolutely independent. It, however, has to be adequately independent. 'And that must be evidenced by both its structural and operational autonomy.' The judgment resolved two cases initially brought separately - one by businessman Hugh Glenister, the other by the Helen Suzman Foundation (HSF), notes Business Day. Because both cases challenged the Hawks legislation on the grounds of independence, the two were joined. Glenister's case - that the Hawks could never be independent while located in the SAPS, which was rife with corruption - was rejected by the court. -

JSC Rejects Hlophe Bid for Recusal of Five Members

Legalbrief | your legal news hub Thursday 30 September 2021 JSC rejects Hlophe bid for recusal of five members The Judicial Service Commission (JSC) will for the first time hold an inquiry that could be the prelude to the impeachment of a judge, after it rejected a request that five of its members should recuse themselves, says a report in the The Sunday Independent. The JSC, which met at the weekend to consider the complaints by the Constitutional Court and Cape Judge President John Hlophe, found that in view of the 'conflict of fact' on papers before it, oral evidence would be required from both sides. The report quotes an unnamed leading senior counsel as saying: 'The inquiry that is going to be held is of huge importance. If this matter is proved, it is difficult to imagine anything more serious.' The request for recusal by counsel for Hlophe was based on concerns that he would not get a fair hearing because last year the five had felt the Judge President should face a gross misconduct inquiry relating to his 'moonlighting' for the Oasis group of companies. At the time, during the Oasis matter, the JSC had been split largely on racial lines, and it was Chief Justice Pius Langa who cast the deciding vote that saw Hlophe escape an inquiry that could have led to his impeachment. According to a report on the News24 site, JSC spokesperson Marumo Moerane said both parties made presentations regarding the future conduct of the matter. He said notice of the date and venue of the oral hearing would be made known once arrangements had been finalised. -

Inventory of the Private Collection of HF Verwoerd PV93

Inventory of the private collection of HF Verwoerd PV93 Contact us Write to: Visit us: Archive for Contemporary Affairs Archive for Contemporary Affairs University of the Free State Stef Coetzee Building P.O. Box 2320 Room 109 Bloemfontein 9300 Academic Avenue South South Africa University of the Free State 205 Nelson Mandela Drive Park West Bloemfontein Telephone: Email: +27(0)51 401 2418/2646/2225 [email protected] PV93 Dr HF Verwoerd FILE NO SERIES SUB-SERIES DESCRIPTION DATES 1/1/1 1. SUBJECT 1/1 Afrikaner Correspondence regarding the Ossewa 1939-1947 FILES unity movements Brandwag-movement, Dr D.F. Malan's rejection of the Ossewa Brandwag- movement and National-Socialistic attitudes; the New Order-movement of Adv. Oswald Pirow; plea for the acknowledgement of Gen. J.B.M. Hertzog as Afrikaner leader in order to sustain Afrikaner- unity; Dr Verwoerd's view as chief editor of Die Transvaler regarding reporting on the Ossewa Brandwag-movement and tie Opposition; notes of Dr Verwoerd regarding the enmity between the leaders of the Ossewa Brandwag and the National Party; minutes of meetings concerning Afrikaner-unity. 1/1/2 1. SUBJECT 1/1 Afrikaner Cuttings regarding Gen. E.A. Conroy on 1941-1942 FILES unity movements the future of the Afrikaner Party after the war; Dr J.F.J. Van Rensburg, leader of the Ossewa Brandwag, concerning republicanism; Adv. Oswald Pirow and the New Order Party; differences of opinion between the Re-united Party and the Ossewa Brandwag-movement and the rejection of the political ideals of the Ossewa Brandwag 1/1/3 1. -

A Brief History of the North West Bar Association

THE BAR IN SA was a circuit court. This led to an arrangement being made between the A brief history of the North West Bar and advocates who were employed Bar Association as lecturers at the Law Faculty of the newly established University of LCJ Maree SC, Mafikeng Transkei in terms of which lecturers were allowed to practise on a part-time basis. Thus in 1978, Don Thompson, Birth and name (Judge-President of the High Court of Bophuthatswana), F Kgomo (Judge Brian Leslie, Joe Renene and Selwyn In an old dilapidated minute book, the President of Northern Cape High Court) Miller (presently the Acting Judge following is to be found on the first and Nkabinde, Leeuw and Chulu President of the Transkei Division) all page: 'Ons, die ondergetekendes, stig (deceased) Uudges of the High Court of became members of the Society. hiermee 'n organisasie wat bekend sal Bophuthatswana). A number of our staan as die Balie van Advokate van The membership of the Society grew members have acted as judges in various Bophuthatswana, ook bekend as die steadily during the 1980s. New members divisions and Lever SC has also acted in Balie van Bophuthatswana. Die grond included Tholie Madala (a justice of the the High Court of Botswana. Our mem wet van die Vereniging is hierby aange Constitutional Court from its inception), bers have chaired various commissions heg as Bylae A.' The 'stigtingsakte' as Peter Rowan, Peter Barratt, Joe Miso, during the period when commissions of they called it, was signed by Advocates enquiries were fashionable. Vic Vakalisa (upon his return), Digby JJ Rossouw, TBR Kgalegi and LAYJ Koyana, Nona Goso, Sindi Majokweni, Thomas on 17 March 1981 at Mafikeng.