Opening Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Health Industry Business Communications Council

Health Industry Business Communications Council Registered Labelers: Accredited Auto-ID Labeling Standards Argentina New MedTek Devices Pty Ltd Oxavita SRL Norseld Pty Ltd. Novadien Healthcare Pty Ltd The following companies Odontit S.A. (and/or their subsidiaries/ PAMPAMED S.R.L. Numedico Technologies Pty Ltd divisions) have applied PATEJIM SRL Opto Global Pty. Ltd. for a Labeler Identification Orthocell Limited Code (LIC) assignment with Austria Prolotus Technologies Pty Ltd HIBCC*. By doing so, they afreeze GmbH Red Milawa Pty Ltd dba Magic Mobility have demonstrated their AMI GmbH SDI Limited commitment to patient safety Bender Medsystems GmbH Signostics Ltd. and logistical efficiency for BHS Technologies GmbH Sirtex Medical Pty Ltd their customers, the industry Metasys Medizintechnik GmbH Smith & Nephew Surgical Pty. Ltd. and the public at large. PAA Laboratories GmbH Staminalift International Limited Safersonic Medizinprodukte Handels The Pipette Company Pty. Ltd. Any organization that is GmbH Thermo Electron Corporation interested in using the HIBC W & H Dentalwerk Burmoos GmbH Vush Pty Ltd uniform labeling system may apply for the assignment of VUSH STIMULATION Australia one or more LICs. William A Cook Australia Pty. Ltd. Adv. Surgical Design & Manufacture, Ltd. Last updated 9-21-2021 AirPhysio Pty Ltd Belgium Annalise-AI Pty Ltd 3M Europe Apollo Medical Imaging Technology Pty Advanced Medical Diagnostics SA/NV Ltd Analis SA/NV Benra Pty Ltd dba Gelflex Laboratories Baxter World Trade Bioclone Australia Pty. Ltd. Bio-Rad RSL Candelis, Inc. Bio-Rad Lab Inc Clinical Diag. Group DePuy Australia Pty. Ltd. Biosource Europe SA For more information, please dorsaVi Ltd Cilag NV contact the HIBCC office at: EC Certification Service GmbH Coris Bioconcept Fink Engineering Pty Ltd Fuji Hunt Photographic Chemicals NV 2525 E. -

I4i Makes the Patent World Blind Michael J

COMMENTS i4i Makes the Patent World Blind Michael J. Conway† All patents receive a presumption of validity pursuant to 35 USC § 282. Courts have traditionally put this presumption into practice by requiring inva- lidity to be established by clear and convincing evidence. The Supreme Court reaffirmed this understanding of the presumption in Microsoft Corp v i4i Ltd Partnership. District courts have divided, however, on whether to require clear and con- vincing evidence when the challenger seeks to invalidate a patent for covering inel- igible subject matter. The conflict originates from a concurrence written by Justice Stephen Breyer in i4i, in which he stated that a heightened standard of proof—like the clear and convincing standard—can apply only to issues of fact, not issues of law. Because subject-matter eligibility has traditionally presented an issue of law, some courts hold that subject-matter-eligibility challenges cannot be subjected to the clear and convincing standard. Other courts agree with that sentiment but would apply the clear and convincing standard to resolve any underlying issues of fact. Still others maintain that subject-matter-eligibility challenges must be estab- lished by clear and convincing evidence. This Comment resolves this ambiguity by showing that subject-matter- eligibility challenges must be established by clear and convincing evidence. It com- pares subject-matter-eligibility challenges to two other patent validity challenges: the on-sale bar and nonobviousness. These two comparisons show that patent law has consistently failed to confine the clear and convincing standard to issues of law. In fact, the standard has been imposed without regard for the distinction be- tween issues of law and fact. -

Healthcare & Life Sciences Industry Update

Healthcare & Life Sciences Industry Update August 2011 Member FINRA/SIPC www.harriswilliams.com What We’ve Been Reading August 2011 • The biggest story from inside the Beltway over the last month was the battle and eventual deal to raise the U.S. debt ceiling to avoid an impending August 2nd default. The Budget Control Act of 2011 will raise the debt ceiling by $2.1-$2.4 trillion, while reducing spending by approximately $2.1 trillion over the next decade. In an interesting post-deal analysis, Michael Hiltzik of the Los Angeles Times notes that despite the protracted negotiations over a broad spectrum of cost-cutting measures, healthcare was not raised as a primary issue. Some have found this especially concerning, considering the outsized portion of the Federal Budget currently allocated to healthcare spending, which is forecast to rise in the coming years. A recent article in The Economist, entitled “Looking to Uncle Sam” makes this point and goes further to suggest that Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) actuaries may be underestimating future increases in Medicare and Medicaid spending. • One potential reason CMS actuaries may be underestimating the future costs of Medicare and Medicaid relates to healthcare reform’s effect on employee benefits, and specifically, the 2014 switch to subsidized exchange policies. A recent report by McKinsey & Company estimates that approximately 30% of employers will stop offering employer- sponsored insurance (ESI) when this switch is made, as opposed to the 7% estimated by the Congressional Budget Office. An ESI exodus of this magnitude could cause substantial strain on an already robust government healthcare budget. -

Healthcare Conference

25th Annual HEALTHCARE CONFERENCE Healthcare Westin St. Francis San Francisco January 8–11, 2007 JPMorgan cordially invites you to attend the 25th Annual Healthcare Conference, January 8 –11, 2007, at the Westin St. Francis in San Francisco. JPMorgan’s premier conference on the healthcare industry will feature more than 260 public and private companies over four days of simultaneous sessions. In addition, the conference will host topical panel discussions featuring leading industry experts. Preliminary List of Invited Presenting Companies Actelion Ltd Baxter International Inc. Cooper Companies Aetna Incorporated BD (Becton, Dickinson) Coventry Affymetrix, Inc. Beckman Coulter, Inc. Dade Behring Holdings, Inc. Alcon, Inc. Bioenvision, Inc. DaVita Inc. Align Technology, Inc. Biogen Idec deCODE genetics, Inc. Allscripts Healthcare Solutions Inc. Biomet, Inc. Digene Altana Boston Scientific Corporation Digirad Corporation — US American Medical Systems Holdings Inc. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company Diversa Corporation Amerigroup Corp. Cambrex Corporation DJO Incorporated AmerisourceBergen Cardinal Health, Inc. Dyax Corp. Amgen, Inc. Caremark Rx, Inc. Eclipsys Corporation AMN Healthcare Services, Inc. Celgene Corporation Edwards Lifesciences Corporation AmSurg Corporation Cell Genesys Elan Corporation, plc Anadys Pharmaceuticals CENTENE Corporation Eli Lilly and Company Applied Biosystems Group Cephalon, Inc. Emdeon Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Cerner Corporation Emergency Medical Services Corporation AstraZeneca Group plc Charles River Laboratories, -

Preliminary Healthcare Agenda 01.03X

29th Annual J.P. Morgan Healthcare Conference January 10 - 13, 2011 Westin St. Francis Hotel, San Francisco, CA Preliminary Conference Agenda SUNDAY, JANUARY 9 - Registration in Tower Salon A - 3 to 9 PM MONDAY, JANUARY 10 - Registration in Tower Salon A - 6:45 AM, Breakfast in Italian Foyer Grand Ballroom Colonial Room California West California East Elizabethan A/B Elizabethan C/D Alexandra's Breakout: Borgia Room Breakout: Georgian Room Breakout: Olympic Room Breakout: Yorkshire Room Breakout: Sussex Room Private Company Track Not-for-Profit Track 7:30 AM Opening Remarks: Doug Braunstein - Chief Financial Officer, JPMorgan Chase & Co., Grand Ballroom Astra Tech 8:00 AM Celgene Corporation Kinetic Concepts, Inc Alkermes, Inc. Biocon Limited Catalent (private company) 8:30 AM Express Scripts Inc. Agilent Technologies Inc. Beckman Coulter Inc. Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc. Quality Systems Axcan Intermediate Holdings 9:00 AM Roche Holding AG Zimmer Holdings, Inc. Genoptix, Inc. ImmunoGen, Inc Health Net Inc. Merrimack Pharmaceuticals Inc. Vertex Pharmaceuticals Allscripts Healthcare Solutions, 9:30 AM Medicis Pharmaceutical Corp. Lonza Group Ltd Henry Schein Inc. Surgical Care Affiliates Incorporated Inc. 10:00 AM Medtronic, Inc. WellPoint, Inc. Onyx Pharmaceuticals Inc. Sigma-Aldrich Corporation Align Technology Inc.* Symphogen 10:30 AM Room Not Available Medco Health Solutions, Inc. Smith & Nephew plc* Medivation, Inc. Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Zeltiq Aesthetics 11:00 AM Room Not Available Merck KGaA Perrigo Company Healthways Incorporated BioMimetic Therapeutics, Inc. Penumbra, Inc. 11:30 AM Room Not Available Dendreon Corporation Gen-Probe Inc. Select Medical Corporation ArthroCare Corporation PTC Therapeutics, Inc. 12:00 PM Luncheon & Keynote: Nancy-Ann DeParle - Counselor to the President and Director of the White House Office of Health Reform, Grand Ballroom Endo Pharmaceuticals Holdings 1:30 PM Room Not Available Amylin Pharmaceuticals Inc. -

HOSPIRA, INC. V. FRESENIUS KABI USA, LLC

United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ______________________ HOSPIRA, INC., Plaintiff-Appellant v. FRESENIUS KABI USA, LLC, Defendant-Appellee ______________________ 2019-1329, 2019-1367 ______________________ Appeals from the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois in Nos. 1:16-cv-00651, 1:17-cv- 07903, Judge Rebecca R. Pallmeyer. ______________________ Decided: January 9, 2020 ______________________ ADAM G. UNIKOWSKY, Jenner & Block LLP, Washing- ton, DC, argued for plaintiff-appellant. Also represented by BRADFORD PETER LYERLA, AARON A. BARLOW, YUSUF ESAT, REN-HOW HARN, SARA TONNIES HORTON, Chicago, IL. IMRON T. ALY, Schiff Hardin LLP, Chicago, IL, argued for defendant-appellee. Also represented by KEVIN MICHAEL NELSON, JOEL M. WALLACE; AHMED M.T. RIAZ, New York, NY. ______________________ Before LOURIE, DYK, and MOORE, Circuit Judges. 2 HOSPIRA, INC. v. FRESENIUS KABI USA, LLC LOURIE, Circuit Judge. Hospira Inc. (“Hospira”) appeals from the judgment of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois that claim 6 of U.S. Patent 8,648,106 (“the ’106 patent”) is invalid as obvious. Hospira, Inc. v. Fresenius Kabi USA, LLC, 343 F. Supp. 3d 823 (N.D. Ill. 2018) (“Opinion”). Because we find that the district court’s fac- tual findings were not clearly erroneous and that those findings support a conclusion of obviousness, we affirm. BACKGROUND Hospira makes and sells dexmedetomidine products under the brand name Precedex, including a ready-to-use product known as Precedex Premix. Hospira owns a num- ber of patents that cover its Precedex Premix product. Fresenius Kabi USA LLC (“Fresenius”) filed an Abbrevi- ated New Drug Application (“ANDA”) seeking approval to enter the market with a generic ready-to-use dexme- detomidine product. -

The Retirement and Savings Plan for Amgen

Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington D.C. 20549 FORM 11-K (Mark One) ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2009 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Commission file number 000-12477 THE RETIREMENT AND SAVINGS PLAN FOR AMGEN MANUFACTURING, LIMITED State Road 31, Kilometer 24.6, Juncos, Puerto Rico 00777 (Full title and address of the plan) AMGEN INC. (Name of issuer of the securities held) One Amgen Center Drive, 91320-1799 Thousand Oaks, California (Zip Code) (Address of principal executive offices) Table of Contents The Retirement and Savings Plan for Amgen Manufacturing, Limited Financial Statements and Supplemental Schedules Years ended December 31, 2009 and 2008 Contents Report of Independent Registered Public Accounting Firm 1 Audited Financial Statements: Statements of Net Assets Available for Benefits at December 31, 2009 and 2008 2 Statements of Changes in Net Assets Available for Benefits for the years ended December 31, 2009 and 2008 3 Notes to Financial Statements 4 Supplemental Schedules: Schedule of Assets (Held at End of Year) 15 Schedule of Assets (Acquired and Disposed of Within Year) 31 Signatures 32 Exhibits 33 Table of Contents Report of Independent Registered Public Accounting Firm Amgen Manufacturing, Limited, as Named Fiduciary, and the Plan Participants of The Retirement and Savings Plan for Amgen Manufacturing, Limited We have audited the accompanying statements of net assets available for benefits of The Retirement and Savings Plan for Amgen Manufacturing, Limited (the Plan) as of December 31, 2009 and 2008, and the related statements of changes in net assets available for benefits for the years then ended. -

New Obviousness Guidelines from the USPTO and Their Impact on Prosecution

New Obviousness Guidelines from the USPTO and Their Impact on Prosecution Anthony C. Tridico & Carlos M. Téllez MAY 9, 2011 ©Finnegan, Henderson, Farabow, Garrett & Dunner, LLP, 2011 1 Disclaimer These materials are public information and have been prepared solely for educational purposes to contribute to the understanding of American intellectual property law. These materials reflect only the personal views of the authors and are not individualized legal advice. It is understood that each case is fact-specific, and that the appropriate solution in any case will vary. Therefore, these materials may or may not be relevant to any particular situation. Thus, the authors and Finnegan, Henderson, Farabow, Garrett & Dunner, L.L.P. cannot be bound either philosophically or as representatives of their various present and future clients to the comments expressed in these materials. The presentation of these materials does not establish any form of attorney-client relationship with the authors or Finnegan, Henderson, Farabow, Garrett & Dunner, L.L.P. While every attempt was made to insure that these materials are accurate, errors or omissions may be contained therein, for which any liability is disclaimed. 2 Agenda y Background on the 2010 Obviousness Guidelines y Discussion of the 2010 Obviousness Guidelines 1) Principles of Obviousness 2) Impact of the KSR decision 3) Obviousness examples from the Federal Circuit 4) Cases related to consideration of evidence by USPTO y Practical considerations on how to approach obviousness rejections { A novel -

Margin Stocks, Notice 97-22

F e d e r a l R e s e r v e B a n k OF DALLAS ROBERT D. MCTEER, JR. _____ p r e s i d e n t DALLAS, TEXAS AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER 75265-5906 March 10, 1997 Notice 97-22 TO: The Chief Executive Officer of each member bank and others concerned in the Eleventh Federal Reserve District SUBJECT Over-the-Counter (OTC) Margin Stocks DETAILS The Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System has revised the list of over- the-counter (OTC) stocks that are subject to its margin regulations, effective February 10, 1997. Included with the list is a listing of foreign margin stocks that are subject to Regulation T. The foreign margin stocks listed are foreign equity securities eligible for margin treatment at broker- dealers. The Board publishes complete lists four times a year, and the Federal Register announces additions to and deletions from the lists. ATTACHMENTS Attached are the complete lists of OTC stocks and foreign margin stocks as of February 10, 1997. Please retain these lists, which supersede the complete lists published as of February 12, 1996. Announcements containing additions to and deletions from the lists will be provided quarterly. MORE INFORMATION For more information regarding marginable OTC stock requirements, please contact Eugene Coy at (214) 922-6201. For additional copies of this Bank's notice and the complete lists, please contact the Public Affairs Department at (214) 922-5254. Sincerely yours, yf f a * / ' . For additional copies, bankers and others are encouraged to use one of the following toll-free numbers in contacting the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas: Dallas Office (800) 333 -4460; El Paso Branch Intrastate (800) 592-1631, Interstate (800) 351-1012; Houston Branch Intrastate (800) 392-4162, Interstate (800) 221-0363; San Antonio Branch Intrastate (800) 292-5810. -

Selected Patent Litigation in the Medical Device Industry

Selected Patent Litigation in the Medical Device Industry Abbott Laboratories Applied Medical Resources Corp. Applied Medical Resources Corp. Applied Medical Resources Corp. v. v. v. v. Pacific Biotech, Inc. Gaya Ltd. Tyco Healthcare dba Covidien United States Surgical Corp. (S.D. Cal.) (C.D. Cal.) (C.D. Cal.), (E.D. Tex.) (C.D. Cal.) Arthrex, Inc. Bard Peripheral Vascular, Inc. Cook Exergen v. v. v. v. DJ Orthopedics LLC Endologix, Inc. Endologix, Inc. SAAT (D. Del.) (D. Ariz.) (S.D. Indiana) (D. Mass.) Flex-Foot, Inc. Fresenius USA, Inc. Hygia Health Services I-Flow Corporation v. v. v. v. CRP, Inc. Transonic Systems, Inc. Masimo Corp. Apex Medical Technologies (C.D. Cal.) (N.D. Cal.) (N.D. Ala.) (S.D. Cal.) Implant Innovations, Inc. Kinetic Concepts, Inc. Kinetic Concepts, Inc. Koepnick Medical & Educational v. v. v. Research Foundation Nobel Biocare, USA, Inc. BlueSky Medical Group Smith & Nephew, Inc. v. Alcon Laboratories, (S.D. Fla.) (W.D. Tex.) (W.D. Tex.) Bausch & Lomb, Inc. (D. Ariz.) Lazarus LifeScan, Inc. Mallinckrodt, Inc. Masimo Corp. v. v. v. v. Endologix, Inc. Can-Am Care Corporation Masimo Corp. Covidien (D. Utah) (N.D. Cal.) (C.D. Cal.) (C.D. Cal.) Masimo Corp. Nellcor Puritan Bennett, Inc. Nobel Biocare, USA, Inc. Optivus Tech., Inc. and v. v. v. Loma Linda Univ. Med. Center Philips Masimo Corp. Blue Sky Bio, LLC v. (D. Del.) (C.D. Cal) (C.D. Cal.) Ion Beam (C.D. Cal.) Princeton Biochemicals, Inc. RAS Holding Corp. et al Sontek Industries, Inc. Springboard Medical Ventures, LLC v. v. v. v. Beckman Coulter, Inc. -

Radford Global Life Sciences Survey Product Overview

Product Overview: Global Life Sciences Survey One Firm. Complete Solutions. Unmatched Life Sciences Expertise Few industries are as diverse as the global life Select Life Sciences Participants: sciences sector. Ranging from multi-national . Abbott Labs . IDEXX Laboratories . Abbvie . Illumina 59 pharmaceuticals to small, pre-commercial start- . Acadia Pharma. Infinity Pharma. Reporting ups, meeting the needs of life sciences firms . Actelion . Intuitive Surgical . Actelion Pharma. Jazz Pharma. Countries around the globe requires a dedicated and . Alkermes . Johnson & Johnson educated team. At Radford, we've assembled . Amgen . Kinetic Concepts . Astellas . Lonza that team, and our highly capable resources are . AstraZeneca . Mannkind ready to handle your unique research, product . Athersys . Medtronic 812 . Baxter . Medivation development, clinical and scientific roles. Beckman Coulter . Merck Participating . Becton Dickinson . Momenta Pharma. Organizations Key Survey Features: . Biogen Idec . Morphosys AG . BioMarin . Novo Nordisk . Unmatched survey scale grants participants access to . Bio-Rad . Pacific Biosciences global compensation intelligence in 59 countries across . Bluebird Bio . Pall 812 biotechnology, pharmaceutical, medical device, . Boehringer Ingelheim . Parexel International 1,900 diagnostic and CRO companies . Bristol-Myers Squibb . Patheon Pharma. Celgene . Peregrine Pharma. Unique Jobs . Celldex . Pfizer Surveyed . Full global consistency creates a harmonized structure . Cerus . PPD for data submissions, job matching and market . Covance . PRA International comparisons across all business operations in 65 . Covidien . Qiagen Gmbh surveyed countries . Daiichi Sankyo . Quintiles . Dyax . Regeneron Pharma. 390 . Complete compensation coverage includes base . Eli Lilly . Sanofi Aventis salaries, allowances, fixed compensation, bonus and . Exelixis . Shire Thousand . F. Hoffman Roche . St. Jude Medical incentive targets, total cash compensation, stock options, Incumbents . Genomic Health . Sunesis Pharma. restricted stock awards and more . -

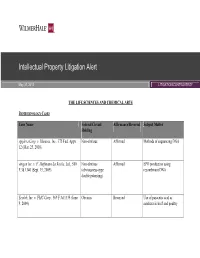

Intellectual Property Litigation Alert

Intellectual Property Litigation Alert May 31, 2012 LITIGATION/CONTROVERSY THE LIFE SCIENCES AND CHEMICAL ARTS BIOTECHNOLOGY CASES Case Name Federal Circuit Affirmance/Reversal Subject Matter Holding Applera Corp. v. Illumina, Inc., 375 Fed. Appx. Non-obvious Affirmed Methods of sequencing DNA 12 (Mar. 25, 2010) Amgen Inc. v. F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd., 580 Non-obvious Affirmed EPO production using F.3d 1340 (Sept. 15, 2009) (obviousness-type recombinant DNA double patenting) Ecolab, Inc. v. FMC Corp., 569 F.3d 1335 (June Obvious Reversed Use of paracetic acid as 9, 2009) sanitizer in beef and poultry Case Name Federal Circuit Affirmance/Reversal Subject Matter Holding Pharmastem Therapeutics, Inc. v. Viacell, Inc., Obvious (2-1) Reversed Compositions and methods for 491 F.3d 1342 (July 9, 2007) treating persons with compromised blood and immune systems with hematopoietic stem cells 2 Holdings of Non-obviousness (50%) 2 Reversals (50%) 2 Holdings of Obviousness (50%) 2 Affirmances (50%) MEDICAL DEVICE CASES Case Name Federal Circuit Affirmance/Reversal Subject Matter Holding Bard Peripheral Vascular, Inc. v. W.L. Gore & Non-obvious (2-1) Affirmed Prosthetic vascular grafts Assocs., 670 F.3d 1171 (Feb. 10, 2012) fabricated from ePTFE Retractable Techs., Inc. v. Becton, Dickinson and Non-obvious Affirmed Retractable syringes Co., 653 F.3d 1296 (July 8, 2011) Spectralytics, Inc. v. Cordis Corp., 649 F.3d Non-obvious Affirmed Coronary stents 1336 (June 13, 2011) Case Name Federal Circuit Affirmance/Reversal Subject Matter Holding Spine Solutions, Inc. v. Medtronic Sofamor Non-obvious Affirmed Intervertebral implants Danek USA, Inc., 620 F.3d 1305 (Sept. 9, 2010) Trimed, Inc.