THE MAKING of UPPINGHAM As Illustrated in Its Topography and Buildings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Joiner Information 2020

SCHOOL BUS SERVICE 2020-21 Services operate from Monday to Friday in term time. Route 4 and Route 5 include Saturday mornings. Routes 1: Foxton, 2: Tur Langton and 3: Market Harborough operated through A&S coaches, www.aandscoaches.com Routes 4: Stamford or 5: Balderton run by Oakham School minibus fleet. Pick-up points, times and fares are below. Fares 2020-21 Day Pupils Flexi/Transitional When booking please specify Termly fares 10 journeys a week Boarders whether you are booking for Routes 1, 2 and 3 £565 £480 a Day pupil or a Flexi / Route 4 £370 £315 Transitional boarder. Route 5 £595 £515 Pick-up Points and Times Route 1 Foxton – Kibworth – Tilton-on-the-Hill – Oakham Morning Evening Mon & Fri Tues & Wed Thurs Foxton 07.15 Oakham 18.10 17.00 17.15 Kibworth 07.20 Tilton-on-the-Hill 18.30 17.20 17.35 Tilton-on-the-Hill 07.40 Foxton 18.55 17.45 18.00 Oakham 08.05 Kibworth Drop 1 19.03 17.52 18.07 Kibworth Drop 2 19:05 17:55 18:10 Pick up points Foxton Swing Bridge Street on the corner of Hogg Lane Kibworth Morning: large lay-by on the A6 Evening: Drop 1: large lay-by on the A6, Drop 2: near The Swan Tilton-on-the-Hill Shop/Post Office on Oakham Road Route 2 Leicester – Oadby – Kibworth – Tur Langton – Billesdon – Oakham Morning Evening Mon & Fri Tues & Wed Thurs Leicester 07:00 Oakham 18.05 17.00 17.15 Oadby 07:10 Billesdon 18.30 17.25 17.40 Kibworth 07:20 Tur Langton 18.40 17.35 17.50 Tur Langton 07.30 Kibworth 18:50 17:45 18:00 Billesdon 07.40 Oadby 19:05 17.55 18:10 Oakham 08.05 Leicester 19:15 18:05 18.20 Pick up points Leicester Train Station, London Road Oadby Morning: Esso fuel station Bus stop. -

Digital Rutland Strategy 2019-2022

Digital Rutland Strategy 2019-2022 Version V1.0 This page is left intentionally blank 1 Contents Foreword ................................................................................................................................................ 3 1.0 Our Vision ....................................................................................................................................... 4 2.0 Overview - Our Digital Strategy Aims ......................................................................................... 4 3.0 Aim 1: Building on Superfast Broadband Connectivity ............................................................ 5 4.0 Aim 2: Accelerating Full Fibre Coverage in Rutland ................................................................ 7 5.0 Aim 3: Facilitating 4G and 5G Mobile Broadband Networks ................................................. 10 6.0 Aim 4: Connecting Businesses to New Opportunities ........................................................... 15 7.0 Aim 5: Enabling Digital Delivery and Service Transformation .............................................. 17 8.0 Aim 6: Ensuring Digital Inclusion ............................................................................................... 18 9.0 Strategic Alignment ..................................................................................................................... 22 10.0 Expected Benefits ..................................................................................................................... 25 11.0 Next -

Shared Ownership – Sales, Re-Sales and Allocations Policy

Shared Ownership – Sales, Re-sales and Allocations Policy 1. Introduction This policy outlines Uppingham Homes Community Land Trust (UHCLT) approach to the sale and allocation of shared ownership homes. Shared Ownership provides a solution to the housing needs of those who would otherwise not be eligible for social housing nor be able to buy on the open market. Such households often work in sectors where incomes have not kept pace with increases in house prices. Our focus is on young people classed as being under the age of 35 with a local connection (residence, family or employment) to the Rutland parishes of Preston, Wing, Glaston, Bisbrooke, Seaton, Lyddington, Thorpe By Water, Caldecott, Stoke Dry, Belton, Wardley, Ridlington, Ayston and Uppingham. This policy supports UHCLT obligations relating to sales allocations in accordance with the Homes England Capital Funding Guide. 2. Aims • To establish a sales process that is non-discriminatory and responsive to demand, while contributing to the need to be inclusive and ensure sustainable communities. • To establish an efficient, transparent, fair and effectively controlled basis for the acceptance and processing of applications for low cost home ownership. • To provide a system of prioritising applicants ensuring that homes are allocated to people in housing need and to those whom shared ownership is an appropriate solution. • To ensure UHCLT meets its social objectives whilst recognising the financial importance of selling properties promptly. Shared Ownership Sales, Re-sales and Allocations Policy March 2020 • To ensure that UHCLT complies with all financial and regulatory controls including those set out in the Homes England Capital Funding Guide. -

Welland View Glaston Road | Uppingham | Rutland | LE15 9EU WELLAND VIEW

Welland View Glaston Road | Uppingham | Rutland | LE15 9EU WELLAND VIEW • Established Family Home in Private Position on the Outskirts of Uppingham • Offering Much Improved Spacious and Well Maintained Accommodation Throughout • Sitting Room, Library, Office, L-Shaped Kitchen / Dining Room • Master Bedroom Suite Comprising Dressing Room, Walk-in Wardrobe & En Suite • Three Further Double Bedrooms and Family Bathroom • Self-Contained Annex with Sitting Room, Kitchen, Two Bedrooms & Bathroom • Total Plot of Circa 3/4 acre with Mature Landscaped Gardens • Double Garage with Ample Off-Road Parking for a Number of Vehicles • Selection of Outbuildings Including Garaging, Workshop and Garden Store • Total Accommodation Excluding Outbuildings Extends to 2997 Sq.Ft. Within a seven minute walk of the charming town of Uppingham in Rutland, stands an attractive home originally from the seventies, which has been completely renovated, almost rebuilt, in recent years and has become the most perfect family home. Welland View sits on a private and tranquil plot of nearly an acre enclosed by mature trees. It not only has three to four bedrooms in the main part of the house, but two further bedrooms in the adjoining annex, with even more potential for conversion of the garaging and workshops (subject to planning). Approached from a quiet road linking the town with the A47, Welland Views’ entrance is off a shared drive with a pretty and small, independent garden centre, providing a number of benefits. “If I had a choice of who to have as a neighbour,” divulges the owner, “ I would choose a garden centre. We rarely hear any noise from there, and my mother-in-law loves visiting it when she comes to stay! As they shut at five, we can have a noisy party and not need to worry. -

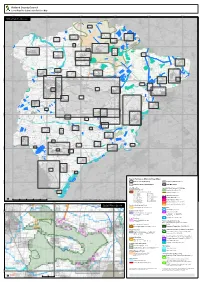

Rutland Main Map A0 Portrait

Rutland County Council Local Plan Pre-Submission Policies Map 480000 485000 490000 495000 500000 505000 Rutland County - Main map Thistleton Inset 53 Stretton (west) Clipsham Inset 51 Market Overton Inset 13 Inset 35 Teigh Inset 52 Stretton Inset 50 Barrow Greetham Inset 4 Inset 25 Cottesmore (north) 315000 Whissendine Inset 15 Inset 61 Greetham (east) Inset 26 Ashwell Cottesmore Inset 1 Inset 14 Pickworth Inset 40 Essendine Inset 20 Cottesmore (south) Inset 16 Ashwell (south) Langham Inset 2 Ryhall Exton Inset 30 Inset 45 Burley Inset 21 Inset 11 Oakham & Barleythorpe Belmesthorpe Inset 38 Little Casterton Inset 6 Rutland Water Inset 31 Inset 44 310000 Tickencote Great Inset 55 Casterton Oakham town centre & Toll Bar Inset 39 Empingham Inset 24 Whitwell Stamford North (Quarry Farm) Inset 19 Inset 62 Inset 48 Egleton Hambleton Ketton Inset 18 Inset 27 Inset 28 Braunston-in-Rutland Inset 9 Tinwell Inset 56 Brooke Inset 10 Edith Weston Inset 17 Ketton (central) Inset 29 305000 Manton Inset 34 Lyndon Inset 33 St. George's Garden Community Inset 64 North Luffenham Wing Inset 37 Inset 63 Pilton Ridlington Preston Inset 41 Inset 43 Inset 42 South Luffenham Inset 47 Belton-in-Rutland Inset 7 Ayston Inset 3 Morcott Wardley Uppingham Glaston Inset 36 Tixover Inset 60 Inset 58 Inset 23 Barrowden Inset 57 Inset 5 Uppingham town centre Inset 59 300000 Bisbrooke Inset 8 Seaton Inset 46 Eyebrook Reservoir Inset 22 Lyddington Inset 32 Stoke Dry Inset 49 Thorpe by Water Inset 54 Key to Policies on Main and Inset Maps Rutland County Boundary Adjoining -

Uppingham Every Wednesday

1281 Jun 5 Fair granted on the Feast of St. Margaret the Virgin and morrow. 1281 Jun 5 Market granted to Uppingham every Wednesday. 1335 May 26 The two mother churches of Uppingham & Werlea and the & 18 Edw houses of Wilfuninus the priest and all thereto belonging, III granted by Edward the Confessor to the Abbey Church of Westminster on 28 December 1066 (examined). 1374 ND 1. On Thursday after St. Michael 48 Edw 3, Beatrix Skinner is charged that on Monday after St Gregory 44 Edw 3 she stole from William of Rockingham at Uppingham one bushel of barley worth 12d and ½ bushel of oats worth 3d. Verdict, not guilty. 2. Also Alicia daughter of Thomas Bene of Uppingham is charged that on Tuesday after the Conversion of St Paul 38 Edw III, she stole 5 geese & 4 hens worth 40d from John o’ the Greene and others serving William de Rockingham, at Uppingham. Verdict, not guilty. 1484 Feb 17 John Gardener of Barkeby with others unknown on the Thursday next after St Valentine 2 Ric III, came to the house of Thomas Saddler of Uppingham and broke his doors & stole one knife worth 2d. 1489 ND Chapel of SS Trinity, Uppingham. 1489 ND Linc Wills ref Wolsey, Atwater 1521 ND Sir Henry Atkinson, Curate of Uppingham. 1523 ND Sir Henry Parkinson, parish priest of Uppingham. 1526 ND Randolf Greene of Uppingham pardoned for the murder of iv.2132 John Mickal. 1538 ND The same Thomas More not paying 20s for a levy made towards the repair of the organ there. -

BRONZE AGE SETTLEMENT at RIDLINGTON, RUTLAND Matthew Beamish

01 Ridlington - Beamish 30/9/05 3:19 pm Page 1 BRONZE AGE SETTLEMENT AT RIDLINGTON, RUTLAND Matthew Beamish with contributions from Lynden Cooper, Alan Hogg, Patrick Marsden, and Angela Monckton A post-ring roundhouse and adjacent structure were recorded by University of Leicester Archaeological Services, during archaeological recording preceding laying of the Wing to Whatborough Hill trunk main in 1996 by Anglian Water plc. The form of the roundhouse together with the radiocarbon dating of charred grains and finds of pottery and flint indicate that the remains stemmed from occupation toward the end of the second millennium B.C. The distribution of charred cereal remains within the postholes indicates that grain including barley was processed and stored on site. A pit containing a small quantity of Beaker style pottery was also recorded to the east, whilst a palaeolith was recovered from the infill of a cryogenic fissure. The remains were discovered on the northern edge of a flat plateau of Northamptonshire Sand Ironstone at between 176 and 177m ODSK832023). The plateau forms a widening of a west–east ridge, a natural route way, above northern slopes down into the Chater Valley, and abrupt escarpments above the parishes of Ayston and Belton to the south (illus. 2). Near to the site, springs issue from just below the 160m and 130m contours to the north and south east respectively and ponds exist to the east corresponding with a boulder clay cap. The area was targeted for investigation as it lay on the northern fringe of a substantial Mesolithic/Early Neolithic flint scatter (LE5661, 5662, 5663) (illus. -

Rutland Camra Bus Information Welcome

RUTLAND CAMRA BUS INFORMATION Barrowden 12 North Luffenham 12 WELCOME! Rutland has a Exeter Arms GBG Fox & Hounds limited, but growing, bus daytime network that does Belton In Rutland 747 Oakham RF1, RF2, 9,19,SL enable beer aficionados to Sun Grainstore GBG sample some pubs without Railway driving. The two principal Caldecott RF1 Captain Noel “hubs” are Oakham and Plough GBG White Lion Uppingham. Rutland is also Hornblower served by a Rail Station in Cottesmore RF2 3 Crowns Oakham, but can also be Sun Wheatsheaf accessed from Corby Station Lord Nelson GBG and then onward to Rutland Edith Weston 12, SL Odd House via RF1 Wheatsheaf Catmose (club) Empingham 9,12 ,SL Ryhall 4 PRINCIPAL BUS SERVICES White Horse Green Dragon RF1 Wicked Witch Oakham-Uppingham-Corby Exton RF2 RF2 Fox & Hounds South Luffenham 12 Oakham –Melton Boot & Shoe 4 Glaston 12 Stamford – Grantham Old Pheasant Uppingham RF1 , 12 ,SL 9 Exeter Arms Oakham- Stamford Great Casterton 9 Vaults Peterborough Plough Don Paddys 12 Falcon Uppingham – Stamford Greetham RF2 Crown GBG 19 Plough Uppingham Football (club) Oakham – Nottingham Black Horse Stamford- Grantham Wheatsheaf Whissendine 19 747 White Lion Uppingham- Leicester Ketton 12 3 Horseshoes Shorelink (SL) Sports and Social Club (club) Circular route Northwick Arms Whitwell 9 Railway Noel Arms Further Information and timetables from Wing RF1 www. Traveline.info Langham 19 Kings head 0871 200 22.33 Noel Arms Kings Head RUTLAND CAMRA does not Wheatsheaf necessarily endorse all pubs mentioned in this guide, Pubs Lyddington RF1 within the Good Beer Guide Exeter Arms are annotated GBG. Full Old White Hart details of pubs mentioned in this publication can be found Manton RF1, SL at: wwww.whatpub.com Horse & Jockey GBG PUBS/ TOWNS/VILLAGES Market Overton RF2 SOME possible TOURS: SERVED BY THE NETWORK Black Bull Town Pub Crawls: Exton Arr: 12.12 Food. -

Rutland County Council

Rutland County Council Catmose Oakham Rutland LE15 6HP. Telephone 01572 722577 Facsimile 01572 75307 DX28340 Oakham COPIES OF AGENDAS / NOTES / PARISH BRIEFING PAPERS AND OTHER RELEVANT PARISH INFORMATION ARE AVAILABLE ON THE RUTLAND COUNTY COUNCIL WEBSITE – www.rutland.gov.uk Notes of a Meeting of the PARISH COUNCIL FORUM held on Monday 18 April 2016 at 7.00pm in the Council Chamber, Catmose, Oakham ---oOo--- Mr Kenneth Bool – Chairman of the Council (in the Chair) ---oOo--- SPEAKERS: Ms Juliet Burgess-Ray Defibrillator Coordinator, The Karen Ball Fund Mr Saverio Della Rocca Assistant Director (s151 officer), Rutland County Council Mr Martin Fagan The Community Heartbeat Trust Councillor Terry King Leader, Rutland County Council Councillor Tony Mathias Deputy Leader, Rutland County Council Ms Karen Mellor Rutland Access Group CLERK TO Miss Marcelle Gamston Corporate Support Officer THE FORUM: APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE: Mr J Atack Braunston Parish Council Mr C Bichard Braunston Parish Council Mr M Clatworthy Tickencote Parish Meeting Mr K Edwards Greetham Parish Council Mrs J Lucas Oakham Town Council Mr K Nimmons on behalf of the members of Cottesmore Parish Council There were 32 County and Parish representatives attending the meeting. A list of representatives who signed the attendance sheet is attached. 1) WELCOME AND INTRODUCTION BY THE CHAIRMAN OF THE COUNCIL The Chairman welcomed all parish representatives to the Parish Council Forum. 2) APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Miss Gamston read the apologies. 3) NOTES OF LAST MEETING The Notes of the Parish Council Forum held on 28 January 2016 were confirmed by parish representatives and signed by the Chairman. 4) MATTERS ARISING FROM THE NOTES OF THE LAST MEETING There were no matters arising from the notes of the last meeting. -

Lyddington Manor History Society Thomas Bryan the Elder, Grazier Of

Lyddington Manor History Society Thomas Bryan the Elder, Grazier of Stoke Dry Will proved 1784 TNA PROB 11/1124/2 1 IN THE NAME OF GOD AMEN 2 I Thomas Bryan the Elder of Stoke Dry in the County 3 of Rutland Grasier (being thanks be to God) of sound and 4 disposing mind memory and understanding but considering 5 the certainty of Death as well as the uncertainty of the 6 time thereof and being desirous to settle my worldly 7 affairs while I have Strength and capacity to make 8 Publish and Declare this my last Will and Testament in 9 Manner and form following (that is to say) First I give 10 and devise all my Lands Tenements and Hereditaments 11 with their and every of their Appurtenances at Gretton 12 in the County of Northampton unto my Nephew Thomas 13 Bryan his heirs and Assigns for ever I also give and 14 devise all and every of my Messuages Cottages Closes 15 Lands Tenements with their and every of their 16 Appurtenances at Liddington Caldecot or Thorpe by 17 Water in the said County of Rutland any or either of 18 them unto my said Nephew Thomas Bryan his Heirs 19 and Assigns for ever I also give and devise unto my 20 said Nephew the said Thomas Bryan all 21 my Messuages Cottages Closes Lands and Tenements with 22 their respective Hereditaments and Appurtenances situate 23 at Great Bowden in the County of Leicester To hold all 24 the same Estate at Great Bowden to him my said Nephew 25 Thomas Bryan his Heirs and Assigns for ever But subject 26 as to the said Estate at Great Bowden only to and 27 charged with and I do hereby give and -

Designated Rural Areas and Designated Regions) (England) Order 2004

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2004 No. 418 HOUSING, ENGLAND The Housing (Right to Buy) (Designated Rural Areas and Designated Regions) (England) Order 2004 Made - - - - 20th February 2004 Laid before Parliament 25th February 2004 Coming into force - - 17th March 2004 The First Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred upon him by sections 157(1)(c) and 3(a) of the Housing Act 1985(1) hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the Housing (Right to Buy) (Designated Rural Areas and Designated Regions) (England) Order 2004 and shall come into force on 17th March 2004. (2) In this Order “the Act” means the Housing Act 1985. Designated rural areas 2. The areas specified in the Schedule are designated as rural areas for the purposes of section 157 of the Act. Designated regions 3.—(1) In relation to a dwelling-house which is situated in a rural area designated by article 2 and listed in Part 1 of the Schedule, the designated region for the purposes of section 157(3) of the Act shall be the district of Forest of Dean. (2) In relation to a dwelling-house which is situated in a rural area designated by article 2 and listed in Part 2 of the Schedule, the designated region for the purposes of section 157(3) of the Act shall be the district of Rochford. (1) 1985 c. -

Barrowden School Was Built in 1862 by the Marquess of Exeter

Barrowden School was built in 1862 by the Marquess of Exeter. Within a year up to 120 pupils were attending. The school was extended in 1872 with the addition of an infants room. The first report by the Head in 1872 was hardly complimentary: ‘The intelligence of the Upper classes requires much cultivation.’ In 1880 the Inspector is scathing and considers that the spelling throughout the school might be better. In 1895 Mr Brittiff Tidd and his wife Agnes were appointed as Headmaster and Mistress. Their eight years of service Barrowden School, now a private house ’greatly improved the village school, and the discipline (and) efficiency.’ Following their departure in 1903, standards declined almost overnight. However by 1905 the Inspector was able to report ‘a decided improvement in the tone, discipline and efficiency of the school.’ In 1973 the children of junior school age were moved to North Luffenham Primary School. For several years, the building continued to be run as an Infant School for three and four year olds. Grantham Journal, 9 May 1903 Bisbrooke (later Bisbrooke and Glaston) School opened in 1872 in the grounds of Bisbrooke Hall. The school could accommodate 64 seniors and 24 infants. A constant concern was over the number of pupils attending as funding was dependent on this. Frequently the attendance officer would be called in to see the parents of absent pupils. Often the reason was illness: ‘A few of the children have been away with blister pox’ (May 1892). ‘Coughing among the children is, at times, most distressing’ (Feb 1901). The School in around 1911 ‘2 or 3 cases of ringworm’ (June 1903).