Women, Magick and Mediumship Assembling a Field of Fascination in Contemporary Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{PDF EPUB} Astrology Through a Psychic's Eyes by Sylvia Browne Browne, Sylvia

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Astrology Through a Psychic's Eyes by Sylvia Browne Browne, Sylvia. American professional psychic, gifted all her life and founder of Nirvana Foundation for Psychic Research in 1974. In her interesting autobiography, Sylvia tells of her lifelong association with her spirit guide, Francine, a South American Indian entity who first took over the girl's body when she was eight. Born with a caul over her face and head, Sylvia came naturally into her gift from a family background of prescience. When she was three, she informed her folks that her sister would be born in three years (as she was) and at five, began to foresee deaths and events that were frightening to a child. Her grandmother, Ada Coil, reassured her that it was a natural gift, and taught her psychic etiquette, such as not babbling inappropriately that her dad was going out to see a girlfriend. At eight, Sylvia became clairvoyant and clairaudient, seeing Francine, and becoming prophetic about future events. She learned to tell people of their mission and soul-work, themes and patterns, but was never able to see her own future. Often flip, funny and down to earth, the sparkling redhead learned to be an entertaining lecturer and was a popular TV guest, a particular favorite of Montel Williams. On 7/13/1954, her beloved Grandma Ada died, followed a few days later by her uncle. Sylvia went to college, majoring in education and planning to teach. She was engaged for four years but at 19, crashed into love with a man who did not mention his wife and two kids. -

Psychic’ Sally Morgan Scuffles with Toward a Cognitive Psychology U.K

Science & Skepticism | Randi’s Escape Part II | Martin Gardner | Monster Catfish? | Trent UFO Photos the Magazine for Science and Reason Vol. 39 No. 1 | January/February 2015 Why the Supernatural? Why Conspiracy Ideas? Modern Geocentrism: Pseudoscience in Astronomy Flaw and Order: Criminal Profiling Sylvia Browne’s Art and Science FBI File More Witch Hunt Murders INTRODUCTORY PRICE U.S. and Canada $4.95 Published by the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry C I Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow www.csicop.org James E. Al cock*, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to David H. Gorski, cancer surgeon and re searcher at Astronomy and director of the Hopkins Mar cia An gell, MD, former ed i tor-in-chief, Barbara Ann Kar manos Cancer Institute and chief Observatory, Williams College New Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine of breast surgery section, Wayne State University John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. School of Medicine. Kimball Atwood IV, MD, physician; author; Clifford A. Pickover, scientist, au thor, editor, Newton, MA Wendy M. Grossman, writer; founder and first editor, IBM T.J. Watson Re search Center. Steph en Bar rett, MD, psy chi a trist; au thor; con sum er The Skeptic magazine (UK) Massimo Pigliucci, professor of philosophy, ad vo cate, Al len town, PA Sus an Haack, Coop er Sen ior Schol ar in Arts and City Univ. -

Gardner on Exorcisms • Creationism and 'Rare Earth' • When Scientific Evidence Is the Enemy

GARDNER ON EXORCISMS • CREATIONISM AND 'RARE EARTH' • WHEN SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE IS THE ENEMY THE MAGAZINE FOR SCIENCE AND REASON Volume 25, No. 6 • November/December 2001 THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION OF CLAIMS OF THE PARANORMAL AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONAL (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO) • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy. State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Research Fellow Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist. York Univ., Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts Loren Pankratz, psychologist. Oregon Health Toronto and Sciences, prof, of philosophy. University Sciences Univ. Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Albany, of Miami John Paulos, mathematician. Temple Univ. Oregon C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist. Univ. of Wales Steven Pinker, cognitive scientist. MIT Marcia Angell, M.D.. former editor-in-chief, Al Hibbs, scientist. Jet Propulsion Laboratory Massimo Polidoro, science writer, author, New England Journal of Medicine Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human under executive director CICAP, Italy Robert A. Baker, psychologist. Univ. of standing and cognitive science, Indiana Univ. Milton Rosenberg, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Chicago Stephen Barrett M.D., psychiatrist, author, Physics and professor of history of science. Wallace Sampson, M.D., clinical professor of consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Harvard Univ. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist. Simon Ray Hyman,* psychologist. Univ. of Oregon medicine, Stanford Univ., editor. Scientific Fraser Univ.. Vancouver, B.C., Canada Leon Jaroff, sciences editor emeritus, Time Review of Alternative Medicine Irving Biederman, psychologist Univ. -

![[803632C] [PDF] the Other Side and Back: a Psychic's Guide to Our World and Beyond Sylvia Browne, Lindsay Harrison](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1515/803632c-pdf-the-other-side-and-back-a-psychics-guide-to-our-world-and-beyond-sylvia-browne-lindsay-harrison-641515.webp)

[803632C] [PDF] the Other Side and Back: a Psychic's Guide to Our World and Beyond Sylvia Browne, Lindsay Harrison

[PDF] The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond Sylvia Browne, Lindsay Harrison - pdf free book Free Download The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond Ebooks Sylvia Browne, Lindsay Harrison, Read Online The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond E-Books, PDF The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond Free Download, Download Free The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond Book, Download Online The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond Book, Download PDF The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond, read online free The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond, by Sylvia Browne, Lindsay Harrison pdf The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond, the book The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond, Sylvia Browne, Lindsay Harrison ebook The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond, Download pdf The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond, Download The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond E-Books, Read Best Book The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond Online, Read The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond Books Online Free, Read The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond Full Collection, Read The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond Ebook Download, Free Download The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond Best Book, The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond Read Download, The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond Full Download, Free Download The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond Books [E-BOOK] The Other Side And Back: A Psychic's Guide To Our World And Beyond Full eBook, CLICK TO DOWNLOAD Keep on reading. -

The Skeptic Contents Vol 25, No 1 Autumn 2005 ISSN 0726-9897 Regulars

the Skeptic Contents Vol 25, No 1 Autumn 2005 ISSN 0726-9897 Regulars Editor ♦ 3 – Editorial — Who to Blame?— Barry Williams Barry Williams ♦ 4 – Around the Traps — Bunyip ♦ 63 – Letters Contributing Editors ♦ 66 - Notices Tim Mendham Steve Roberts Technology Consultant Features Richard Saunders ♦ 6 - Facing Disasters — Rob Hardy Chief Investigator ♦ 8 - Communication Failure — Peter Bowditch Ian Bryce ♦ 10 - Much Ado ... — Sir Jim R Wallaby ♦ 11 - Nutrition Myth: Artificial Sweeteners — Glenn Cardwell All correspondence to: ♦ 14 - The Psychic Skeptic Pt 2 — Karen Stollznow Australian Skeptics Inc ♦ 19 - Pestiferous Laws — Colin Keay PO Box 268 ♦ Roseville NSW 2069 21 - Sensing Nothing — Christopher Short Australia ♦ 23 - Psychics Dealt Out — Anon (ABN 90 613 095 379 ) ♦ 28 - One Strange Brotherhood — Brian Baxter ♦ 32 - The Skeptical Potter — Daniel Stewart Contact Details ♦ 36 - Escaping the Gravitational Pull of the Gospels — David Lewis Tel: (02) 9417 2071 ♦ Fax: (02) 9417 7930 40 - Resting on Shaky Ground — Sue-Ann Post new e-mail: [email protected] ♦ 43 - The Good Word: Language Lapses — Mark Newbrook ♦ 46 - Review: An Amazing Journey — Rob Hardy Web Pages ♦ 48 - Review: Where Do We Go From Here? — Martin Hadley Australian Skeptics ♦ 49 - Review: Memoirs of a Country Doctor — Ros Fekitoa www.skeptics.com.au ♦ No Answers in Genesis 50 - Literature v Literalism — Peter Bowditch http://home.austarnet.com.au/stear/default.htm ♦ 51 - Feedback: Self Help Books — John Malouf ♦ 52 - Feedback: Sex Drugs & Rock ‘n Roll — Loretta Marron the Skeptic is a journal of fact and opinion, ♦ 54 - Forum: When the Cheering Had to Stop published four times per year by Australian ♦ 58 - Forum: Society, Medicine & Alternative Medicine Skeptics Inc. -

King of the Paranormal

King of the Paranormal CNN's Larry King Live has a long history of outrageous promotion of UFOs, psychics, and spiritualists. CHRIS MOONEY roadcast on CNN, the July 1, 2003, installment of Larry King Live was a sight to behold. The program, Bin Kings words, explored "the incredible events of fifty-six years ago at Roswell, New Mexico." What most likely crashed at Roswell in 1947 was a government spy bal- loon, but the panel of guests assembled on King's show pre- ferred a more sensational version of events. Jesse Marcel, Jr., son of a Roswell intelligence officer, claimed that just after the crash, his father showed him bits of debris that "came from another civilization" (Marcel 2003). Glenn Dennis, who worked at a Roswell funeral home at the time, said a military officer called him to ask about the availability of small caskets (i.e., for dead aliens). Later Dennis, obviously SKEPTICAL INQUIRER November/December 2003 a UFO enthusiast, abruptly observed that the pyramids in Roswell crash site. Doleman admitted to King rJiat his dig had Egypt had recently been "[shut down] for three or four days not yet yielded any definitive evidence, but added that the and no tourists going out there on account of the sightings" "results" of his analysis will air on Sci-Fi in October—as (Dennis 2003). opposed to, say, being published in a peer-reviewed scientific King's program didn't merely advance the notion that an journal (Doleman 2003). [See also David E. Thomas, "Bait alien spacecraft crashed at Roswell in 1947. -

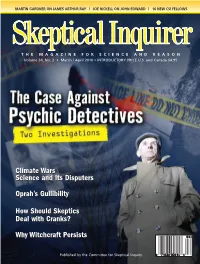

Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah's Gullibility How

SI M/A 2010 Cover V1:SI JF 10 V1 1/22/10 12:59 PM Page 1 MARTIN GARDNER ON JAMES ARTHUR RAY | JOE NICKELL ON JOHN EDWARD | 16 NEW CSI FELLOWS THE MAG A ZINE FOR SCI ENCE AND REA SON Vol ume 34, No. 2 • March / April 2010 • INTRODUCTORY PRICE U.S. and Canada $4.95 Climate Wars Science and Its Disputers Oprah’s Gullibility How Should Skeptics Deal with Cranks? Why Witchcraft Persists SI March April 2010 pgs_SI J A 2009 1/22/10 4:19 PM Page 2 Formerly the Committee For the SCientiFiC inveStigation oF ClaimS oF the Paranormal (CSiCoP) at the Cen ter For in quiry/tranSnational A Paul Kurtz, Founder and Chairman Emeritus Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Richard Schroeder, Chairman Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Ronald A. Lindsay, President and CEO Benjamin Radford, Research Fellow Bar ry Karr, Ex ec u tive Di rect or Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow James E. Al cock, psy chol o gist, York Univ., Tor on to David J. Helfand, professor of astronomy, John Pau los, math e ma ti cian, Tem ple Univ. Mar cia An gell, M.D., former ed i tor-in-chief, New Columbia Univ. Stev en Pink er, cog ni tive sci en tist, Harvard Eng land Jour nal of Med i cine Doug las R. Hof stad ter, pro fes sor of hu man un der - Mas si mo Pol id oro, sci ence writer, au thor, Steph en Bar rett, M.D., psy chi a trist, au thor, stand ing and cog ni tive sci ence, In di ana Univ. -

John Edward: Hustling the Bereaved

INVESTIGATIVE FILES JOE NICKELL John Edward: Hustling the Bereaved uperstar "psychic medium" John by a local printer. He visited dieir spook The great magician Harry Houdini Edward is a stand-up guy. Unlike show and volunteered as part of an audi- (1874—1926) crusaded against phony the spiritualists of yore, who typi- ence committee to help secure the two spiritualists, seeking out elderly mediums S mediums. He took that opportunity to who taught him the tricks of die trade. cally plied their trade in dark-room seances, Edward and his ilk often per- secretly place some printer's ink on the For example, while sitters touched hands form before live audiences and even neck of a violin, and after the seance one around die seance table, mediums had under the glare of TV lights. Indeed, of the duo had his shoulder smeared with clever ways of gaining die use of one Edward (a pseudonym: he was born John the black substance (Nickell 1999). hand. (One method was to slowly move MaGee Jr.) has his own popular show on the hands close togedier so diat die fin- die SciFi channel called Crossing Over, gers of one could be substituted for those "which has gone into national syndication JOHN EDWARD of die other.) This allowed die production (Barrett 2001; Mui 2001). I was asked by of special effects, such as causing a tin television newsmagazine Dateline NBC trumpet to appear to be levitating. to study Edward's act: was he really talk- Houdini gave public demonstrations of ing to the dead? HI the deceptions. -

Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs Vol.4: S - Z

Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs vol.4: S - Z © Neuss / Germany: Bruno Buike 2017 Buike Music and Science [email protected] BBWV E30 Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs - vol.4: S - Z Neuss: Bruno Buike 2017 CONTENT Vol. 1 A-D 273 p. Vol. 2 E-K 271 p. Vol. 3 L-R 263 p. Vol. 4 S-Z 239 p. Appr. 21.000 title entries - total 1046 p. ---xxx--- 1. Dies ist ein wissenschaftliches Projekt ohne kommerzielle Interessen. 2. Wer finanzielle Forderungen gegen dieses Projekt erhebt, dessen Beitrag und Name werden in der nächsten Auflage gelöscht. 3. Das Projekt wurde gefördert von der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Sozialamt Neuss. 4. Rechtschreibfehler zu unterlassen, konnte ich meinem Computer trotz jahrelanger Versuche nicht beibringen. Im Gegenteil: Das Biest fügt immer wieder neue Fehler ein, wo vorher keine waren! 1. This is a scientific project without commercial interests, that is not in bookstores, but free in Internet. 2. Financial and legal claims against this project, will result in the contribution and the name of contributor in the next edition canceled. 3. This project has been sponsored by the Federal Republic of Germany, Department for Social Benefits, city of Neuss. 4. Correct spelling and orthography is subject of a constant fight between me and my computer – AND THE SOFTWARE in use – and normally the other side is the winning party! Editor`s note – Vorwort des Herausgebers preface 1 ENGLISH SHORT PREFACE „Paul Smith“ is a FAKE-IDENTY behind which very probably is a COLLCETIVE of writers and researchers, using a more RATIONAL and SOBER approach towards the complex of Rennes-le-Chateau and to related complex of „Priory of Sion“ (Prieure de Sion of Pierre Plantard, Geradrd de Sede, Phlippe de Cherisey, Jean-Luc Chaumeil and others). -

The Two Movements of Magic

Lite Issue 10 REVIEWS | MASTERCLASS | THE DEALER'S BOOTH | THE TWO MOVEMENTS OF MAGIC THE TEAM Editor: Mark Leveridge Deputy Editor: Graham Hey Design Editor: Phil Shaw Advertisement Enquiries: Mark Leveridge [email protected] Website Design: www.magicdp.co.uk Circulation: Sarah Logan Circulation Assistants: Frankie Shaw, Edward Shaw, Jessica Preece Contributors: Oliver Tabor, Gregg Webb Reviewers: Mark Leveridge, Paul Preager, Stuart Bowie, Chris Payne, Jay Fortune, Phil Shaw Magicseen’s management board consists of: Graham Hey, Mark Leveridge & Phil Shaw General enquiries and comments: t's a pleasure to welcome you to the pages of our latest free taster issue of Magicseen, the contents [email protected] for which have been selected from issue 95 (Nov 2020) of the full Magicseen Magazine. Thanks to: Rafael, Vinny Sagoo Our main feature article highlights the Belgian maestro Rafael, who updates us on how he has been using Ithe extra time afforded by the pandemic to work on his unique new show. We also hear from award winning magician Oliver Tabor who takes us behind the scenes of his ambitious Zoom magic show - and it certainly took more than a laptop and a webcam! SUBSCRIPTIONS Online at www.magicseen.com, or Do you fidget or sway when you're performing at a table side? Are you guilty of too much backward and sending your details and a cheque forward movement when entertaining from a cabaret floor or stage? These are the topics we highlight in our payable to ‘Magicseen’ to Magicseen advice article entitled The Two Movements Of Magic. Subscriptions, Anne's Park, Cowley, Exeter EX5 5EN, UK. -

Grv33 Web.Pdf

1 Volume 33 • Spring 2018 2 The Gallatin Review. Table of Contents Poetry Managing Editors Prose Managing Editors Visual Arts Managing Editors Grace McGuan, Anaïs Kessler, Sarah Hahn, Daniels Mekšs 01 — prose 12 — visual art Lana Scibona Prashanth Moturi Ramakrishna Kindergarten Soup Two Wheels Visual Arts Editors Derick McCarthy Miguel Volar Poetry Editors Prose Editors Addie Walker, Dara Yen Emily Bellor, MariVi Madiedo, Julianna Bjorksten, Lauren White-Jackson, Lachlan Hyatt, Lezhou Jiang, PEP Editors 02 — poetry 13 — visual art Isabel Wilson Savannah Summerlin Keyli Peralta, Lana Scibona The Oak & the Vine Fulton Street Emilie Weiner Wenkai Wang Faculty Advisor Sara Murphy 04 — poetry 15 — visual art Designer Portrait in Dread Marble Gun Kyle Richard Emmanuel Carrillo Sam Cheng Production Editor Sam Patwell 05 — visual art 16 — visual art Modified Bone Canyon Lights Senior Director, Writing Program Harry Fink Jimi Stine June Foley Assistant Director, Writing Program 06 — prose 17 — visual art Allyson Paty Office #243 Sprawl Mark Etem Elaine Lo Prison Education Program Nikhil Pal Singh, Faculty Director Rachael Hudak, Administrative Director 09 — poetry 18 — visual art Raechel Bosch, Assistant Director of Communications Race-ism Bodysong Richa Lagu, Student Assistant Omar Padilla Harry Fink Alexis Myrie, Student Assistant Special Thanks To 10 — poetry 19 — poetry Susanne Wofford, Dean of the Gallatin School In Defense of Muzak What is America? Millery Polyné, Associate Dean for Faculty and Academic Affairs Henry Sheeran Rayvon Gordon -

Poteri Cold Reading

/ Studio Frasson Consulenza di Direzione e Supporto Certificazione Sistemi di Gestione per la Qualità COMPANY CERTIFIED UNI EN ISO 9001:2000 / Poteri "psichici" Tratto da "Bizarre Beliefs", pagg. 63-71. Di Simon Hoggart e Mike Hutchinson, Burtler & Tanner Ltd., Frome & London, ISBN 1-57392-456-4 (acquistabile su Prometeo, la libreria online del Cicap). Traduzione di © Alessia Guidi. A chiunque sia capitato esprimere qualche dubbio su indovini, spiritualisti, chiaroveggenti, lettura della mano, sfere di cristallo o tarocchi, sicuramente si è sentito dire molte volte: «Beh, sono andata da un'indovina e mi ha detto che l'anno dopo avrei sposato un uomo biondo. Dopo un mese ho conosciuto Jeremy. Come te lo spieghi?»; oppure «Oh, sono d'accordo che in queste cose non c'è nulla di vero, ma lui sapeva che mia madre era malata, e addirittura che avevamo un'auto blu!» Sono cose di poco conto se si sta scherzando dopo una buona cena tra amici, e non vengono a costare più di un giro di drink. Tuttavia alcuni "lettori" chiedono somme ingenti - a volte anche centinaia o migliaia di sterline - sostenendo di essere in grado di fornire conoscenza utile sul futuro, o messaggi di conforto dai defunti. Informazioni che paiono miracolose e inspiegabili - come il nome di una persona cara, o più banali - come il colore di un'auto, ovviamente lasciano stupefatti i più creduli. Mescolate ingenuità umana, dolore per una perdita, ignoranza sulle tecniche usate e il fatto che tutti vorremmo sapere che cosa ci riserva il futuro, ed otterrete un terreno fertile per imbroglioni e ciarlatani.