North East Retail and Leisure Study One North East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Eco-Trend As a New Tendency in the Fashion Industry and Its Influence on Modern Design

THE ECO-TREND AS A NEW TENDENCY IN THE FASHION INDUSTRY AND ITS INFLUENCE ON MODERN DESIGN AUTHORSHIP INTRODUCTION Svitlana Oborska Global environmental problems have become Docent, Associate Professor of the Department of Event one of the reasons for the formation of a new Management and Leisure Industry Kyiv National University of the Culture and Arts, Associate Professor of the Department of Event concept in design. In the fashion industry, the Management and Leisure Industry, Kyiv National University of the Culture and Arts. term "environmental sustainability" or "conscious fashion" - the safe use of the ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3148-6325 E-mail: [email protected] planet's natural resources and ensuring Liudmyla Bilozub environmental and social safety - is becoming increasingly common. Professor assistant, PhD in History of Arts, Zaporizhzhia National University. It is known that clothes should not only ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2384-827X aesthetic, but also have a direct physiological E-mail: [email protected] impact on people, so clothing design has Oksana Minenko rapidly responded to the need for a conscious Associate Professor at the Department of Design of the Faculty of approach to environmental issues. The search Art and Design, Candidate of Art and Criticism, Department of Design of the Faculty of Art and Design, Municipal Institution of for new materials, new methods of natural Higher Education "Khortytsia National Educational Rehabilitation dyeing of fabrics, the use of recycled fibers in Academy" of Zaporizhzhia Regional Council. weaving, the restoration of traditional crafts ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4210-5778 that are used in clothing production - all this E-mail: [email protected] has grown from an unpopular theory to a Oleksandra Penchuk stable and generally applied practical activity Candidate of Technical Sciences, Associate Professor, under the general definition of eco-design. -

Introduction

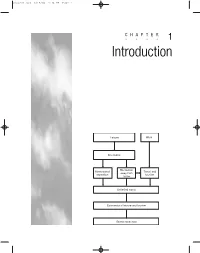

Chap-01.qxd 8/17/04 3:34 PM Page 1 CHAPTER •••• 1 Introduction Leisure Work Recreation Recreation Home-based Travel and away from recreation tourism home Unlimited wants Economics of leisure and tourism Scarce resources Chap-01.qxd 8/17/04 3:34 PM Page 2 The Economics of Recreation, Leisure and Tourism Objectives and learning outcomes • How important are recreation, leisure and tourism to national economies? • Why do these industries provide so many new jobs? • What is the globalization of recreation and leisure? • Are recreation, leisure and tourism shares good investments? • Is the growth of recreation, leisure and tourism sustainable? This book will help you investigate these issues. The objectives of this chapter are to define and integrate the areas of study of this book. First the scope of recreation, leisure and tourism will be discussed, and second the scope and techniques of economics will be outlined. The final part of the chapter explains how the study area of recreation, leisure and tourism can be analysed using economic techniques. By studying this chapter students will be able to: • understand the scope of recreation, leisure and tourism and their interrelationship; • explain the basic economic concerns of scarcity, choice and opportunity costs; • outline the allocation of resources in different economic systems; • explain the methodology of economics; • understand the use of models in economics; • understand the use of economics to analyse issues in recreation, leisure and tourism; • access sources of information. Definition and scope of recreation, leisure and tourism Like all definitions, those pertaining to recreation, leisure and tourism encounter some problems. -

A Study on the Fashion Styles of the Wellness Kin in the Contemporary Fashion

Journal of Fashion Business Vol. 6, No. 6, pp.19~33(2002) A Study on the Fashion Styles of the Wellness Kin in the Contemporary Fashion Kan, Ho-Sup* and Park, Na-Na Assoc. Prof., Dept. of Fashion Design, Dongduk Women’s University* M.A., Dept. of Fashion Design, Dongduk Women’s University Abstract In the middle of economic and mental riches in the 21st century, the importance of well being and the pursuit of happiness are emerging as the new trend. Thus the lifestyle that values comfortable and practical naturalness and intrinsic merits has come to influence the human life rather than the old showing-off and formal desire. In addition to this, the spread of the five day week has given more leisure time, which has led to the increasing interest in health and leisure. The interest in sports has skyrocketed since the successful holding of the 2002 Korea and Japan World Cup event. All these changes to the lifestyle have contributed to the fusion of luxury wear and sports wear. As the result of the consumers in the 21st century having more classified and upgraded way of living thanks to the settlement of the above-mentioned lifestyle and the enlargement of the leisure sports culture, there has appeared the wellness kin, who value the importance of life and the nature and believe in the idea that they can reconstruct the environment in the way they can enjoy their lifestyle and pursue happiness. They favor healthy fashion items and think much of exercise, nutrition, and rest. They pursue the natural and comfortable style, whose ideas came from simple exercises such as health training and yoga and the easy and comfortable look observed at resorts. -

GCSE Leisure and Tourism 2009 Unit1.Pdf

GCSE Leisure & Tourism – Investigating Leisure & Tourism in a chosen area 2.1.2 A Introduction to Leisure and Tourism Leisure Every person has things that they have to do. Many adults have to go to work; someone has to do the shopping, prepare meals, and clean the house and so on. Students and children have to go to school or college and may have homework projects to do after school has finished. Also, every person has to sleep, wash and shower usually for somewhere between 6 to 8 hours each night. When all these things have been completed there is time left over, and this time is a person’s leisure time. During this time, people choose to do what they enjoy doing rather than what they have to do. Put another way: Leisure time is the opportunity available to a person after completing the immediate necessities of life. During this time the person has the freedom to choose what activities to take part in. Another term used is a person’s free time. Some people choose to do very little in their leisure time and may watch television, listen to music or read a newspaper. All of these are very popular leisure activities. They are all things which many people choose to do because they can be done at home and cost very little money. Also, they are activities which people can enjoy on their own. Each person can decide what to do in their leisure time and there are many factors which influence this choice, including the age of the person, their family and friends, their religion and culture, the money they have to spend on leisure and where they live. -

Constructive Suggestions on the Development of Leisure Sports

6th International Conference on Electronic, Mechanical, Information and Management (EMIM 2016) Constructive Suggestions on the Development of Leisure Sports Industry in Ganzhou Renzhuo Zhang School of Science, Jiangxi University of Science and Technology, Ganzhou, China [email protected] Keywords: Ganzhou; Leisure sports; Industry; Suggestion Abstract. This article studies the current situation of leisure sports industry in Ganzhou by using literature consultation, interview method and field research method. And through relevant researches on the current situation, problems existing in the development of leisure sports industry had been found, and thus corresponding suggestions were proposed: create good leisure sports environment to attract tourists from various places and promote further development of this industry; then enhance propaganda, and establish scientific leisure sports values, the development of leisure sports should be connected with the nationwide fitness campaign tightly; the school should establish new educational philosophy; pay more attention on cultivating social sports instructors, popularize red sports to boost the development of leisure sports industry. Introduction Leisure time is an inevitable rules for social development, “the coming of the leisure time” would provide opportunity for the development of leisure sports development, and as a cultural, scientific and healthy ways of life, it could help people gain spiritual motivations for life at the same time of promoting healthy development of both the body and the mind, it plays an important role in increasing the overall quality of people; also, has significant effect on promoting the development of industrial economy and the society and interpersonal communication, the vitality of the sports cause and the perfection of the life-long education system. -

Local Communities' Incentives for Forest Conservation

LOCAL COMMUNITIES’ INCENTIVES FOR FOREST CONSERVATION: CASE OF KAKAMEGA FOREST IN KENYA By Paul Guthiga1* and John Mburu1 A Paper Presented at the 11th Biannual Conference of International Association for the Study of Common Property (IASCP) Bali, Indonesia June 19th to June 23rd 2006 Survival of the Commons: Mounting Challenges and New Realities 1Center for Development Research (ZEF), University of Bonn, Walter-Flex-Str. 3, D53113 Bonn, Germany * Corresponding author: Tel +49-228-731731, Fax +49-228-731869, E-mail: [email protected] The authors would like to express their grateful appreciation to the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) for providing funding for this study through the Biodiversity Analysis Transect for Africa (BIOTA)-East project. ABSTRACT The study is based on a biodiversity-rich remnant of a tropical rainforest located in western Kenya under immense threat of survival. The forest is located in a densely populated area inhabited by poor farming communities. Currently the forest is managed by three management regimes each carrying out its function in a different manner. The study identifies, describes and where possible quantifies the various conservation incentives (both economic and non-economic) offered by the three management regimes. Further, the study analyses local people’s perception of management regimes by generating management satisfaction rankings; both overall and for specific management aspects. The findings of the study indicate that extraction of direct forest products is the main incentive offered by two of the regimes. The local people obtain substantial financial benefits in the form of products they extract from the forest. Satisfaction ranking showed that the strictest regime among the three was ranked highest overall for it performance. -

Study on the New Pathway of Ecological Poverty Alleviation an Forest Health Industry Integrated Development

American Journal of Environmental Science and Engineering 2020; 4(4): 70-74 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ajese doi: 10.11648/j.ajese.20200404.14 ISSN: 2578-7985 (Print); ISSN: 2578-7993 (Online) Study on the New Pathway of Ecological Poverty Alleviation an Forest Health Industry Integrated Development Weitao Xu 1, Heding Shen 1, Liqiang Zhang 1, Laicheng Yang 2, *, An Mao 2, *, Yifu Yuan 2, * 1Planning and Design Institute of Forest Products Industry of National Forestry and Grassland Administration, Beijing, China 2College of Forestry, Shandong Agricultural University, Taian, China Email address: *Corresponding author To cite this article: Weitao Xu, Heding Shen, Liqiang Zhang, Laicheng Yang, An Mao, Yifu Yuan. Study on the New Pathway of Ecological Poverty Alleviation an Forest Health Industry Integrated Development. American Journal of Environmental Science and Engineering . Vol. 4, No. 4, 2020, pp. 70-74. doi: 10.11648/j.ajese.20200404.14 Received : December 4, 2020; Accepted : December 14, 2020; Published : December 22, 2020 Abstract: Forest has the function of nourishing body and mind, promoting health, enhancing human immunity, which is of great significance to improve health index. Forest health care can give full play to the advantages of forest landscape, environment, space and culture, and extend forest functions. It is a new industry integrating forestry, health services, tourism and leisure industry, and is a new trend of sustainable development of forestry. Ecological poverty alleviation is a kind of poverty alleviation -

Chichester Local Development Framework: Tourism Research

Chichester Local Development Framework: Tourism Research Final Summary Report for Tourism Development at Chichester District Council Prepared by Tourism South East February 2006 40 Chamberlayne Road Eastleigh Hampshire, SO50 5JH Tel: 023 8062 5400 www.industry.visitsoutheastengland.com Chichester Tourism LDF Research Report Contents Page 1 Background 2 2 Strategic objectives 2 3 The importance of tourism to Chichester District’s economy 3 4 Environment policy and tourism development in the countryside 3 5 Attractions 4 6 Seasonal Variations 4 7 Rural Accommodation 6 8 Hotel Development 16 9 Cycling and Equestrian Tourism 19 10 The Manhood Peninsula 21 11 Access 25 Appendices Appendix One – Rural Accommodation Appendix Two – Hotel Futures Study Appendix Three – Cycling and Equestrian Tourism Appendix Four – Manhood Peninsula Appendix Five – TSE Guidance Notes: rural pubs, B&Bs, Hotel investment. Tourism South East Development Services 1 Chichester Tourism LDF Research Report 1 Background Tourism South East (TSE) was commissioned by Chichester District Council’s (CDC) Tourism Development Team to provide an independent view on tourism development in Chichester District. The aim of the project was to carry out product development research; the outcomes of which would be used by the Tourism Development Team to inform their internal reporting on tourism spatial policy to the Local Development Framework (LDF) Committee. This client summary and appendices of detailed research is not therefore intended to directly inform the LDF Committee, but rather to provide technical detail for officers. 1.1 Key Outputs of the Summary Report TSE was asked to concentrate on specific geographical divisions of the District (the rural area to the North of the City, the City itself and the Manhood Peninsula), addressing the following four core product areas for spatial policy: 1. -

June 2005 Global Hotel Management Agreement Trends

244161_JLL_HotelTopics 25/5/05 4:43 PM Page 1 June 2005 Global Hotel Management Agreement Trends BEST WESTERN HOLIDAY INN DAYS INN MARRIOTT HOTELS, RESORTS AND SUITES COMFORT INNS & SUITES RAMADA SHERATON HOTELS SUPER 8 HAMPTON INN HILTON HOTELS RADISSON HOTELS & RESORTS MOTEL 6 HOLIDAY INN EXPRESS QUALITY INNS, HOTELS & SUITES HYATT REGENCY COURTYARD BY MARRIOTT GOLDEN TULIP MERCURE TRAVELODGE HILTON INTERNATIONAL IBIS HOWARD JOHNSON NOVOTEL WESTIN DOUBLETREE HOTELS ECONO LODGE RIU HOTELS CROWNE PLAZA INTER-CONTINENTAL EMBASSY SUITES LA QUINTA INNS FAIRFIELD INN RESIDENCE INN RED ROOF INN RENAISSANCE HOTELS & RESORTS CLUB MED VILLAS & VILLAGES WYNDHAM HOTELS & RESORTS STERLING HOTELS SUMMIT HOTELS & RESORTS LE MERIDIEN PRINCE HOTELS EXTENDED STAY AMERICA MELIA HOTELS SOFITEL DISNEY HOTELS FORMULE 1 CLARION CAMPANILE FOUR POINTS SCANDIC HOTELS KNIGHTS INN FAIRMONT HOTELS SLEEP INN & SUITES BAYMONT INNS HOMESTEAD VILLAGE SHANGRI-LA HOTELS WASHINGTON HOTELS NIKKO HOTELS POSTHOUSE COUNTRY INNS & SUITES BY CARLSON BARCELO SOL HOTELS ETAP OMNI HOTELS SUBURBAN LODGE JIN JIANG FOUR SEASONS HOTELS CONCORDE DORINT HOTELS MICROTEL INN & SUITES IBEROSTAR AMERISUITES TRAVEL INN SHERATON LUXURY COLLECTION ADAM'S MARK RITZ-CARLTON TRYP HOTELS SUNROUTE OCCIDENTAL HOTELS HUSA WESTCOAST PREMIERE CLASSE HOMEWOOD BY HILTON RODEWAY INN TREFF THISTLE HOTELS GRAND HYATT FIESTA HOTELS MARITIM LTI HOTELS ORBIS HOTELS HAWTHORN SUITES TOKYU INNS GRECOTEL BEST INNS & SUITES NH HOTELES RICA HOTELS VILLAGER G.S.M. HOTELS CANDLEWOOD SUITES SUN DRURY INN RINGHOTELS -

Family Tree: Global Hotel Companies and Their Brands

Family Tree: Global hotel companies and their brands This family tree is organized by parent company and lists hotel brands that had properties open as of 31 December 2014. PARENT COMPANY BRAND PARENT COMPANY BRAND 25Hours Hotels 25Hours Hotels Arcadia Hotels Af Arcadia Hotels Af 7 Days Inn 7 Days Inn Archipelago International Aston International A Victory Hotels A Victory Hotels Archipelago International Fave Hotels Abad Group Abad Hotels & Resorts Archipelago International Kamuela Villas Abba Abba Archipelago International Neo Hotels Abotel Abotel Archipelago International Quest Hotels Abou Nawas Abou Nawas Arcona Hotels Arcona Hotels Absolute Hotel Services Group Eastin Arcotel Hotels Arcotel Hotels Absolute Hotel Services Group Eastin Easy Aristos Hotels Aristos Hotels Absolute Hotel Services Group U Hotels & Resorts Arora Arora Accor Adagio City Aparthotel Aryaduta Hotel Group Aryaduta Hotel Accor All Seasonshotels As Hotels As Hotels Accor Caesar Park Hotels Ascott Group Ascott Accor Coralia Ascott Group Citadines Accor Etap Hotel Ascott Group Somerset Hotels Accor Grand Mercure Ashok Ashok Accor Hotel F1 Atahotels Atahotels Accor Hotel Formule 1 Atlantic Hotels Atlantic Hotels Accor Hotel Ibis Atton Hotels S.a. Atton Hotel S.a. Accor Ibis Budget Austria Trend Hotels & Resorts Austria Trend Hotels & Resorts Accor Ibis Styles Avari Hotels Avari Hotels Accor Libertel Axel Hotels Axel Hotels Accor Mercure Hotels Ayre Hoteles Ayre Accor Mgallery Hotel Collection Ayres Hotels Ayres Accor Novotel Hotels Azalai Hotels Azalai Hotels Accor -

Serviced Visitor Accommodation in Lincolnshire

Serviced Visitor Accommodation in Lincolnshire Development Strategy & Action Plan FINAL April 2009 DRAFT Locum Consulting 9 Marylebone Lane London W1U 1HL United Kingdom Tel +44 (0)20 7487 1799 Fax +44 (0)20 7487 1797 [email protected] www.locumconsulting.com Date: 13 January 2012 Job: J0895 File: j0895 lincolnshire hotel development strategy 310309.doc All information, analysis and recommendations made for clients by Locum Consulting are made in good faith and represent Locum’s professional judgement on the basis of information obtained from the client and elsewhere during the course of the assignment. However, since the achievement of recommendations, forecasts and valuations depends on factors outside Locum’s control, no statement made by Locum may be deemed in any circumstances to be a representation, undertaking or warranty, and Locum cannot accept any liability should such statements prove to be inaccurate or based on incorrect premises. In particular, and without limiting the generality of the foregoing, any projections, financial and otherwise, in this report are intended only to illustrate particular points of argument and do not constitute forecasts of actual performance. Locum Consulting is the trading name of Locum Destination Consulting Ltd. Registered in England No. 3801514 J0895 Lincolnshire Hotel Development Strategy Contents 1. Introduction 7 2. Summary of Action Plan 8 2.1 Hotel and Pub Excellence Programme 8 2.2 Planning and Economic Development Initiatives 9 2.3 Planning and Economic Development Initiative specifically -

Le Marché Hôtelier Au Royaume-Uni ……………………………………………………………

Le marché hôtelier au Royaume-Uni Par la Mission Économique de Londres Octobre 2002 Document réalisé par Marie BANCAL Revu par Alain GAUGRIS Mission Economique1 de Londres 21 Grosvenor Place - Londres SW1X 7HU Tél. : 00 44 207 235 7080 - Fax : 00 44 207 235 8598 - http://www.dree.org/gb Résumé Le Royaume-Uni est le pays d’Europe où il y a le plus d’hôtels (50 549 en 2000). Grandes chaînes internationales et petits établissements indépendants se côtoient sur un marché atomistique, théâtre de nombreuse fusions et acquisitions ces dernières années. Des chaînes telles que Heritage, Posthouse, Principle ou encore Swallow, sont ainsi passées d’un groupe à un autre, au gré des recompositions de portefeuille. Parallèlement à cette concentration, deux tendances se confirment : la multiplication des franchises et la présence accrue des investisseurs institutionnels. Au niveau de l’offre, après avoir connu une croissance exceptionnelle, le marché des hôtels économiques semble aujourd’hui arriver à maturité. Le rythme des ouvertures se ralentit, les sites intéressants se faisant plus rares, et les concurrents plus nombreux. Les boutiques hôtels sont, au contraire, en pleine expansion. Ce nouveau concept d’hôtels design à taille humaine séduit de plus en plus de clients, à la recherche d’une alternative à la standardisation. Les appart’hôtels rencontrent également un succès croissant. Très répandue sur le continent américain, la formule séduit de plus en plus au Royaume-Uni. La clientèle des hôtels britanniques est essentiellement nationale et d’affaire : les deux tiers des clients sont en déplacement d’affaire et près des trois quarts sont britanniques.