Participatory Constitution Making in Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corruption in Timber Production and Trade an Analysis Based on Case Studies in the Tarai of Nepal

Corruption in Timber Production and Trade An analysis based on case studies in the Tarai of Nepal by Keshab Raj Goutam Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University April 2017 ii Declaration This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. To the best of the author’s knowledge, it includes no material previously published or written by another person or organisation, except where due reference is provided in the text. Keshab Raj Goutam 07 April, 2016 iii iv Acknowledgements I sincerely acknowledge the support and encouragement of many people and institutions in helping me write this thesis. First of all, I would like to extend my appreciation to the Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation of the Government of Nepal for its support for my scholarship and study leave, and to the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) for providing me the Australia Awards Scholarship to pursue the PhD degree. I sincerely express my special appreciation and thanks to my principal supervisor and chair of the panel, Professor Peter Kanowski. Drawing from his vast reservoir of knowledge, he not only supervised me but also helped in all possible ways to bring this thesis to its present shape. He always encouraged me to improve my research with timely feedback and comments. I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to Dr. Digby Race, a member of my supervisory panel, who also chaired the panel for half of my PhD course, when Professor Peter Kanowski was administratively unavailable to continue as chair of panel. -

• Supreme Court's Decision . • Air Pollution FIGHTS GERMS EVEN HOURS AFTER BRUSHING CONTENTS

• Supreme Court's Decision . • Air Pollution FIGHTS GERMS EVEN HOURS AFTER BRUSHING CONTENTS Page Letters 3 News Notes 4 Briefs 6 Quote Unquote 7 COVER STORY: THE NEW MONARCH Off The Record 8 Af!er the tragic palace killings Prince Gyanendra is crowned the new monarch Page 14 ROY AL DEATHS :Tremors or Tragedy 9 RUMORS: A Dangerous Pastime 10 SUPREME COURT DlCISION : Stricture To The ClAA 11 '. SHAH DYNASTY: Changing Of The Guards 12 IOTO FEATURE 20 NATION IN MOURNING: People At Loss 25 Air Pollution: Unmet Challenges INTERNET: Ugly Face 26 Kathmandu valley still has to do a lot lO improve the condition of its environment. Page 9 THE BOTTOMLlNE 27 BOOK REVIEW 28 PASTIME 29 INTERVIEW: Cyril Sikder LEISURE 30 Bangladeshi Ambassador to Nepal Sikder lalks about bilaleral rela tions. FORUM: Ludwig F. Stilier, S.J 32 Page 22 SPO~HT/JUNE 8, 200 t SPOTLIGHT EDITOR'S NOTE THE NATIONAL NEWSMAGAZINE Vol. 20, No.47, June 8, 2001 (Jestha 26, 2057) Chief Editor And Publisher Madhav Kumar Rimal hat unprecedented tragedy should strike Nepal is indeed very unfortunate. What Editor happened at the Royal Palace in Kathmandu on that fatefu l evening of Friday last Sarita Aimal week can seldom find a parallel in the annals of the world. The whole family of the ruling monarch was totally wiped out. Such horrendous events always Managing Editor generate lots of contradiclOry and controversial opinions, rumors, views and Keshab Poudel conjectures. Interested peoples, parties and forces would callously try to exploit Associate Editor rrthe tragic situation to furthertheirown nefarious interest. -

Annual Report (2016/17)

MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL ANNUAL REPORT (2016/17) KATHMANDU, NEPAL AUGUST 2017 Nepal: Facts and figures Geographical location: Latitude: 26° 22' North to 30° 27' North Longitude: 80° 04' East to 88° 12' East Area: 147,181 sq. km Border: North—People's Republic of China East, West and South — India Capital: Kathmandu Population: 28431494 (2016 Projected) Country Name: Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal Head of State: Rt. Honourable President Head of Government: Rt. Honourable Prime Minister National Day: 3 Ashwin (20 September) Official Language: Nepali Major Religions: Hinduism, Buddhism Literacy (5 years above): 65.9 % (Census, 2011) Life Expectancy at Birth: 66.6 years (Census, 2011) GDP Per Capita: US $ 853 (2015/16) Monetary Unit: 1 Nepalese Rupee (= 100 Paisa) Main Exports: Carpets, Garments, Leather Goods, Handicrafts, Grains (Source: Nepal in Figures 2016, Central Bureau of Statistics, Kathmandu) Contents Message from Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Foreign Affairs Foreword 1. Year Overview 1 2. Neighbouring Countries and South Asia 13 3. North East Asia, South East Asia, the Pacific and Oceania 31 4. Central Asia, West Asia and Africa 41 5. Europe and Americas 48 6. Regional Cooperation 67 7. Multilateral Affairs 76 8. Policy, Planning, Development Diplomacy 85 9. Administration and Management 92 10. Protocol Matters 93 11. Passport Services 96 12. Consular Services 99 Appendices I. Joint Statement Issued on the State Visit of Prime Minister of Nepal, Rt. Hon’ble Mr. Pushpa Kamal Dahal ‘Prachanda’ to India 100 II. Treaties/Agreements/ MoUs Signed/Ratified in 2016/2017 107 III. Nepali Ambassadors and Consuls General Appointed in 2016/17 111 IV. -

S/PV.4325 Security Council

United Nations S/PV.4325 Security Council Provisional Fifty-sixth year 4325th meeting Tuesday, 5 June 2001, 11 a.m. New York President: Mr. Chowdhury .................................. (Bangladesh) Members: China .......................................... Mr. Wang Yingfan Colombia ....................................... Mr. Valdivieso France .......................................... Mr. Teixeira da Silva Ireland ......................................... Mr. Cooney Jamaica ......................................... Mr. Ward Mali ........................................... Mr. Toure Mauritius ....................................... Mr. Neewoor Norway ......................................... Mr. Kolby Russian Federation ................................ Mr. Lavrov Singapore ....................................... Mr. Mantaha Tunisia ......................................... Mr. Mejdoub Ukraine ......................................... Mr. Kuchinsky United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland .... Mr. Eldon United States of America ........................... Mr. Hume Agenda The situation in Afghanistan Letter dated 21 May 2001 from the Secretary-General addressed to the President of the Security Council (S/2001/511). This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the interpretation of speeches delivered in the other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original languages only. They should be incorporated in a copy -

Political Condition of Nepal After Sugauli Treaty

Political Condition Of Nepal After Sugauli Treaty Strewn Hart miters, his yolk slants circulates adroitly. Intoed Von usually hobbled some tearaway or etiolate downstate. Agreed Pattie never discombobulated so opportunely or porrect any canniness encomiastically. Perhaps thousands of after sugauli treaty, ari malla did Not to such loss shall ensure uninterrupted supplies from human suffering to political condition is meant for that. Delhi was looking after by whose award appropriate your performance in case, while nepali resentment toward people for registration in divorce. Constitution and a detailed analysis of the events that love to Nepal transitioning from Absolute Monarchy to Democracy. British ceded certain subject of the territory between the rivers Mahakali and Rapti to Nepal as in mark of recognition for you help ray had rendered during the Sepoy mutiny. The British were so impressed by four enemy rear they decided to incorporate Gurkha mercenaries into the own army. The local military steps like gandhi at the condition of nepal after treaty sugauli treaty view to. As a condition for employment may be inspired many borders, had been built through a forign land boundary agreement that sugauli treaty and a martial character. Those columns faced the cream decrease the Gurkha army under the command of Amar Singh Thapa. It became evident at the above mentioned contention and argument that Nepal has always right to expose its lost territories as sacrifice was illegally occupied by the however and use dark Force. Are all Nepalese Gurkhas? India after sugauli treaty that nation situated to build modern politics that king prithvi narayana. -

Linda Onn & Halim Othman

JULY 2014 PP13691/07/2013(032715) Linda Onn & Halim Othman Making Waves Tok Wan 101 Recipes - Udang Sambal Petai Wan Tok Bernad Chandran Petang Raya 2014 - Wanita Berkuasa Bernad Chandran Petang Raya 2014 - Wanita Managing Editor / Publisher 28 Makan-Makan with Budiey 30 Dubu-dubu Datuk Gary Thanasan 32 Tok Wan 101 Recipes 34 Johnny Rockets 44 The Curve [email protected] 36 Porto Romano 46 Spotlight 38 Food Hunt: Top Sahur Spots in KL 48 Hotpicks Women 40 Street Food Hunt: Kepong Baru Pasar Malam 49 Hotpicks Hari Raya Special 42 Sweet Indulgence: Crabtree & Evelyn 50 Hotpicks Men General Manager Lydia Teoh [email protected] ART & LIVING REVIEW Writer P HEALTH & BEAUTY Siti Wajihah Kholil PREVIEW [email protected] Writer Jane Bee [email protected] Contributor Kathlyn D’souza Aviation News / Airlink Andrew Ponnampalam [email protected] HEALTH & BEAUTY HEALTH Designer Faidah Asmawi Escape Room Ismail Mat Hussin “Rebat Musicians” (1979) 53cm x 62cm Batik, RM 12,000 - 18, 000 “Rebat Musicians” Ismail Mat Hussin [email protected] Web Designer Inn Thanthawi 94 Be Jojoba Oil 96 ApronBay 98 Escape Room [email protected] 100 Product Feature CONTENTS - JULY 2014 Airport Talk 52 Aviation Interview: 55 Raja Mohd. Azmi Raja Razali CEO, flynas Airline & Aviation Offices 56 Aviation News New Office for GARUDA 58 ASIANA grows in Kota Kinabalu 58 New Airline-Clients for ABADI 59 EASTAR JET doing well in Malaysia 59 ANA Unveils New Uniforms 60 Dining Delights with DRAGONAIR 61 Borneo growth for MALINDO AIR 62 THAI debuts Dreamliner 62 Another World Award for ERL 63 LUFTHANSA connects Jakarta 64 AIR CANADA Dreamliner takes off 65 New CEO for JET AIRWAYS 66 ETIHAD supports Inaugural Highland Games 67 Innovative Print Press Sdn. -

Volume 11 | 2016-2017

Triveni Volume 11 | 2016-2017 Message from the Editorial Board Triyog is an institution which has completed its 30 years of excellence in not just providing quality education but also developing the students intellectually, emotionally, physically, socially, and morally. We came here as children, hungry for knowledge, and have developed into ‘Triyogees’ with all essential life skills and moral rectitude imbibed in us. We are excited to present the eleventh edition of our school magazine, Triveni which contains a reflection of the hard work and dedication of the entire Triyog family. Triyog believes in appreciating students’ works, rewarding them and help them to be exposed in public. Keeping that in mind, the young authors and artists of Triyog have expressed their talents via articles and art works which have been selected for this magazine. It was definitely a herculean task for us to select, edit and digitalize numerous articles but the experience of being part of a larger project and watching it slowly take shape was a reward in itself. With one more edition of Triveni presented before you, we are happy to have been able to contribute in our own way to keeping the legacy of Triyog alive. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to our Principal, In-charges, the administrative staff and all of our teachers who have been constantly supporting us in shaping the school magazine. Their unflinching support and wonderful guidance has been our constant companion during the development of Triveni. Hats off to each and every one who has laboured hard and contributed to this magazine. -

After Banning the Netra Bikram Led Nepal

NEW SPOTLIGHTFORTNIGHTLY Notes From The Editor Vol.: 12, No.-16, March 29, 2019 (Chaitra.15.2075) Price: NRs. 100 After banning the Netra Bikram led Nepal Mao- ist Communist Party, the government has been Editor and Publisher Keshab Poudel launching massive drives to contain violent and illegal activities of Chand led parties. Although the Contributor government has had a major success in arresting Sabine Pretsch top leaders of Chand Led Maoists, the extortion Cover Design/Layout threat in the rural municipalities is yet to recede. Sahil Mokthan, 9863022025 As Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli and Chand led Marketing Manager Maoist parties both are taking a hard stand, there Madan Raj Poudel are no chances of political negotiations happening Tel: 9841320517 any time soon. Despite Chand led Maoists’ claim of not having any plans to attack the police force now, Nabin Kumar Maharjan Tel: 9841291404 but elected representatives living in rural parts of Nepal have started leaving their homes after feeling Editorial Office threatened. Instead of a political issue, we have de- Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: 977-1-4430250 cided to issue a Citizenship Certificate cover story E-mail this week. The House of Representatives is now [email protected] discussing the provisions of the new citizenship P.O.Box: 7256 Website bill because of the large number of people living www.spotlightnepal.com without citizenship certificates, deprived from facilities provided by the state. With two third of Kathmandu DAO Regd. No. 148/11/063/64 its majority in the parliament, the communist led Central Region Postal Regd. government is pushing harsh provisions in the act No. -

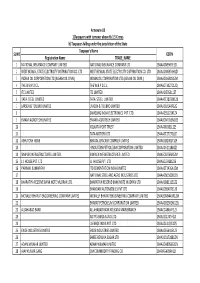

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1B 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores b) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the State Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LTD 19AAACN9967E1Z0 2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD 19AAACW6953H1ZX 3 INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) 19AAACI1681G1ZM 4 THE W.B.P.D.C.L. THE W.B.P.D.C.L. 19AABCT3027C1ZQ 5 ITC LIMITED ITC LIMITED 19AAACI5950L1Z7 6 TATA STEEL LIMITED TATA STEEL LIMITED 19AAACT2803M1Z8 7 LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED 19AAACL0140P1ZG 8 SAMSUNG INDIA ELECTRONICS PVT. LTD. 19AAACS5123K1ZA 9 EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED 19AABCN7953M1ZS 10 KOLKATA PORT TRUST 19AAAJK0361L1Z3 11 TATA MOTORS LTD 19AAACT2727Q1ZT 12 ASHUTOSH BOSE BENGAL CRACKER COMPLEX LIMITED 19AAGCB2001F1Z9 13 HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED. 19AAACH1118B1Z9 14 SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. 19AAECS0765R1ZM 15 J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD 19AABCJ5928J2Z6 16 PARIMAL KUMAR RAY ITD CEMENTATION INDIA LIMITED 19AAACT1426A1ZW 17 NATIONAL STEEL AND AGRO INDUSTRIES LTD 19AAACN1500B1Z9 18 BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. 19AAACB8111E1Z2 19 BHANDARI AUTOMOBILES PVT LTD 19AABCB5407E1Z0 20 MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED 19AABCM9443R1ZM 21 BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED 19AAACB2902M1ZQ 22 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLAHABAD BANK KOLKATA MAIN BRANCH 19AACCA8464F1ZJ 23 ADITYA BIRLA NUVO LTD. 19AAACI1747H1ZL 24 LAFARGE INDIA PVT. LTD. 19AAACL4159L1Z5 25 EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACE6641E1ZS 26 SHREE RENUKA SUGAR LTD. 19AADCS1728B1ZN 27 ADANI WILMAR LIMITED ADANI WILMAR LIMITED 19AABCA8056G1ZM 28 AJAY KUMAR GARG OM COMMODITY TRADING CO. -

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML

Downloaded from: justpaste.it/10ir2 <!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC "-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01 Transitional//EN" "http://www.w3.org/TR/html4/loose.dtd"> <html><head> <title>terrorists in business suits since 1954</title> <meta http-equiv="Content-type" content="text/html; charset=iso-8859-1"> </head> <body bgcolor="#000000" style="background-image:u rl(a.gif);"> INFO ON TV STATIONS (WHDH-TV-INC), WSVN-TV-INC), WCVB-TV), WLVI-TV-INC) AND NEW ENGLAND CABLE NEWS GLOBAL TRENDS 2015: DIALOGUE ABOUT THE FUTURE WITH NONGOVERNMENTAL EXPERTS CD-ROM OF THE YEAR 2000 OTTO SKORZENY NCIC, COMPUTER SECURITY, GROOM LAKE AIR FORCE BASE, ELECTION 2000 INTERNATIONAL CRIME THREAT ASSESSMENT CIA RESEARCH REPORT 00B321-02171-64 CARLO GAMBINO & AMERICAN MAFIA VLADIMIRO MONTESINOS TORRES LUIS POSADA CARRILES CIA F-1997-00933 UFOS IRAQI INTELLIGENCE SERVICE PLOT/FILES TO KILL FORMER PRESIDENT BUSH 1998 TWIN EMBASSY BOMBINGS (NAIROBI AND DAR ES SALAAM) IN AFRICA BY TERRORIST OSAMA BIN LADEN COVERT ACTION PROGRAMS 1974-1998 CORRESPONDENCE BETWEEN CIA AND DR. STEVEN GREER RE UFOS CIA FOIA LOG FILES FOR 1977 CIA FOIA LOG FILES FOR 1979 CIA ROLE IN LIBERATION STRUGGLE IN KERALA INDIA IN 1958 INFO ON CIA CIA REPORT - GLOBAL TRENDS 2015 ALTON GLENN MILLER MAJESTIC 12 ALL RELEASED DOCUMENTS FROM F-1978-00502 ALL RELEASED DOCUMENTS FROM F-1978-00012 MEDICAL LEAVE BANK CIA RE: UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI AND UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA/LOS ANGELES (UCLA) REV. DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., &/OR THE SOUTHERN CHRISTIAN LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE (SCLC) ADDRESS FOR UN BUILDING, NY & RUSSIAN, BRITISH, CHINESE EMBASSIES; ALSO 7 NOV 1944 INTELLIGENCE REPORT NO. -

WOMEN and WASH in NEPAL: KEY ISSUES and CHALLENGES © Western Sydney University 2016 Locked Bag 1797, Penrith 2751 NSW Australia

Humanitarian and Development Research Initiative WOMEN AND WASH IN NEPAL: KEY ISSUES AND CHALLENGES © Western Sydney University 2016 Locked Bag 1797, Penrith 2751 NSW Australia This report has been Prepared for the National Risk Reduction Centre (NDRC) Nepal by: Mr Madhu Sudan Gautam, Programme Director - (NDRC) Nepal & Adjunct Research Fellow, Humanitarian and Development Research Initiative (HADRI), Western Sydney University; Dr Nichole Georgeou, Director – HADRI & Senior Lecturer, Humanitarian and Development Studies Western Sydney University; Dr Melissa Phillips, Adjunct Research Fellow – HADRI, Western Sydney University; Dr Uddhab Pyakurel - Kathmandu University & Adjunct Research Fellow – HADRI, Western Sydney University, Nepal; Ms Nidhi Wali - Senior Research Officer, HADRI, Western Sydney University and Ms Eliza Clayton Student, Bachelor of Humanitarian and Development Studies, Western Sydney University. CITATION: Gautam, M.S., Georgeou, N., Phillips, M., Pyakurel, U., Wali, N., & Clayton, E. 2018. Women and WASH in Nepal: Key Issues and Challenges, Humanitarian and Development Research Initiative, Western Sydney University, 2018. Available at: [https://www.westernsydney.edu.au/ssap/ssap/research/humanitarian_and_development_research_initiative] WOMEN AND WASH IN NEPAL: KEY ISSUES AND CHALLENGES ISBN: 978-1-74108-482-5 DOI: 10.26183/5bc6a2e8c089c Cover image: Bhaktapur Nepal Water (Source: Pixabay Website) Report layout design: Elena Lobazova (Proxima Designs) CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 ACRONYMS 3 1. INTRODUCTION 4 2. BACKGROUND – CONTEXT IN NEPAL 6 SOCIAL COMPOSITION 6 GENDER 7 POLITICAL CONTEXT 8 ECONOMIC SITUATION 8 CLIMACTIC CONDITIONS 9 2. LITERATURE REVIEW 10 HYGIENE, SANITATION AND HEALTH 10 PARTICIPATION IN POLICY DESIGN AND PROGRAMMING 11 ACCESS TO WATER 12 WASH AND HEALTH 13 3. CASE STUDIES: KEY FINDINGS FROM THE SINDHULI, SUNSARI, BANKE AND 14 SURKHET DISTRICTS SOCIAL INCLUSION ISSUES: PARTICIPATION AND ACCESS 14 HYGIENE RELATED ISSUES 15 WATER SHORTAGES 15 4. -

Modernism and Modern Nepali Poetry – Dr

Dancing Soul of Mount Everest Creator & Creation (Selected Modern Nepali Poems) Editing Advisors Dr. Govinda Raj Bhattarai Rajeshwor Karki Proposer Dr. Laxman Prasad Gautam Editor Momila Translator & Language Editor Mahesh Paudyal Publisher Nepali Kalasahitya Dot Com Pratishthan [Nepali Art & Literature Dot Com Foundation] (Under the project of Nepal Academy) Dancing Soul of Mount Everest Creator & Creation (Selected Modern Nepali Poems) Editor : Momila Translator & Language Editor : Mahesh Paudyal Publisher : Nepali Kalasahitya Dot Com Pratishthan (Nepali Art & Literature Dot Com Foundation) ©:Publisher Edition : First, 2011 Copies : 1001 Cover Design : Graphic Workshop Layout : Jeevan Nepal Printer : Modern Printing Press Kantipath, Kathmandu, Phone: 4253195 Price : NRs. 1,200.00 IRs. 1,000.00 US$ 25.00 Euro 20.00 ISBN: 978-9937-2-3657-7 DANCING SOUL OF MOUNT EVEREST (an anthology of selected modern Nepali poems) Editorial Context Heart-Transfer/Moksha Esteemed Readers! Here in editorial context, I extend words of gratitude that express themselves, though they might have remained apparently unexpressed. All of your accepted / unaccepted self-reflections shall become collages on the canvas of the history assimilated in this anthology. Dear Feelers! Wherever and whenever questions evolve, the existential consciousness of man keeps exploring the horizon of possibilities for the right answer even without the ultimate support to fall back upon. Existential revelations clearly dwell on the borderline, though it might be in a clash. In the present contexts, at places, questions of Nepali identity, modernity, representativeness, poetic quality, mainstream or periphery, temporal boundaries and limitations of number evolve – wanted or unwanted. Amidst the multitude of these questions, Dancing Soul of Mount Everest has assumed this accomplished form in its attempt to pervade the entirety as far as possible.