The Influence of the Second Wave University Law Schools in the Development of Australian Legal Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monash Law School Annual Report 2011

Law Annual Report 2011 Monash Law School Australia n China n India n Italy n Malaysia n South Africa www.law.monash.edu Contents 1. Introduction to Monash Law School .............................2 9. Law School Activities ...................................................37 9.1 Events .......................................................................................... 37 2. Campuses.......................................................................3 9.2 Public Lectures ............................................................................ 38 2.1 Clayton ........................................................................................... 3 9.3 Book Launches ............................................................................ 40 2.2 Monash University Law Chambers................................................. 3 9.4 Media Involvement ....................................................................... 40 2.3 Monash Education Centre, Prato, Italy ........................................... 3 2.4 Sunway, Malaysia ........................................................................... 3 10. Advancement .............................................................. 41 10.1 Advancement ..............................................................................41 3. Research ........................................................................4 10.2 Monash Law School Foundation Board ......................................41 3.1 Reflections on Research During 2011 ............................................ -

The Place of Lawyers in Politics

THE HON T F BATHURST AC CHIEF JUSTICE OF NEW SOUTH WALES THE PLACE OF LAWYERS IN POLITICS OPENING OF LAW TERM DINNER ∗ 31 JANUARY 2018 1. As a young boy learning his table manners in the 1950s, the old adage “never discuss politics in polite company” was a lesson that was not lost on me. Even for those of you who did not grow up in the era of Emily Post, I am assured the adage still holds true. 2. When I stood here to give this same address last year, I was under the naïve impression that I had given the topic a wide berth. That is, until I woke to the unwelcome image of my face splashed across the front page of the morning paper. So, eager to avoid my naivety being mistaken for political pointedness and at the risk of casting aspersions on the “polite” character of the present company, I’ve decided to throw the old rule book out the window, launch myself into the bear pit and confront the issue head on. Tonight I want to ask: to what extent should lawyers, in their professional capacity, involve themselves in political debate, criticise government policy, or advocate for particular political outcomes. 3. The particular topic was inspired, oddly enough, by an incident which occurred in discussion surrounding the same sex marriage issue. You will recall that Mr Alan Joyce, the Chief Executive Officer of Qantas came out in support of a ‘Yes’ vote at the plebiscite. It was suggested to him that he should stick to his knitting. -

Current Legal Issues Seminar Series 2012 Current Legal Issues Seminar Series 2012

CURRENT LEGAL ISSUES SEMINAR SERIES 2012 CURRENT LEGAL ISSUES SEMINAR SERIES 2012 We are pleased to announce the fourth annual Current Legal Issues Seminar Series for 2012. The series seeks to bring together leading scholars, practitioners and members of the Judiciary in Queensland and from abroad to discuss key issues of contemporary legal significance. Session 1 An action for (serious) invasions of privacy Date: Thursday 7 June 2012 Venue: Banco Court, Supreme Court of Queensland, George Street, Brisbane Speaker: Professor Barbara McDonald, University of Sydney Bruce McClintock S.C., Barrister-at-Law Commentators: Patrick McCafferty, Barrister-at-Law Chair: The Hon Justice Applegarth, Supreme Court of Queensland Overview: Prompted by scandals more from abroad than at home, Australia may be on the cusp of adopting a statutory action for invasions of privacy. Many questions arise, with such an action having potentially wide-ranging ramifications, some beneficial, some not so, for the media and for individual citizens. Can these ramifications be confined by the drafting process? What advantages, other than speed, would a statutory action have over the incremental development of the common law? Can a statutory action more easily resolve the difficult balancing process that must always arise between rights to privacy and the public interest in freedom of speech, both in interlocutory relief and final orders? How does protection of privacy as an interest or right compare with the protection our law provides in other contexts, such as freedom from personal injury or damage to reputation? Depending on the progress of statutory reform at the time, this paper will consider the state of actual and proposed protection from invasions of privacy in Australia, with reference to typical situations, and include comparative perspectives from other jurisdictions grappling with similar issues. -

Macquarie a Smart Investment

Macquarie a smart investment Macquarie is Australia’s best modern university, so you’ll graduate with an internationally respected degree We adopt a real-world approach to learning, so our graduates are highly sought-after. CEOs worldwide rank Macquarie among the world’s top 100 universities for graduate recruitment Our campus is surrounded by leading multinational companies, giving you unparalleled access to internships and greater exposure to the Australian job market You will love the park-like campus for quiet study or catching up with friends among the lush green surrounds Investments of more than AU$1 billion in facilities and infrastructure ensure you have access to the best technology and facilities Our friendly, welcoming campus community is home to students from over 100 countries 2 MacquarIE UNIVERSIty Contents FACULTY OF ARTS 5 Media and creative arts 6 Security and intelligence 8 Society, history and culture 10 Macquarie Law School 14 FACULTY OF BUSINESS AND EcoNOMIcs 17 Business 18 MACQUARIE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT 22 FACULTY OF HumaN SCIENCEs 23 Education and teaching 24 Health sciences 29 Linguistics, translating and interpreting 32 Psychology 35 MEDICINE AND SURGERY 38 FACULTY OF SCIENCE 39 Engineering and information technology 40 Environment 42 Science 47 Higher degree research at Macquarie 50 How to apply: your future starts here 52 English language requirements 54 This is just the beginning: discover more 55 This document has been prepared by the The University reserves the right to vary Marketing Unit, Macquarie University. The or withdraw any general information; any information in this document is correct at course(s) and/or unit(s); its fees and/or time of publication (July 2013) but may the mode or time of offering its course(s) no longer be current at the time you refer and unit(s) without notice. -

Handbook 2000

THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES S nz Faculty of Law HANDBOOK 2000 THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES & Faculty of Law HANDBOOK 2000 Courses, programs and any arrangements for programs including staff allocated as stated in this Handbook are an expression of intent only. The University reserves the right to discontinue or vary arrangements at any time without notice. Information has been brought up to date as at 17 November 1999, but may be amended without notice by the University Council. © The University of New South Wales The address of the University of New South Wales is: The University of New South Wales SYDNEY 2052 AUSTRALIA Telephone: (02) 93851000 Facsimile: (02) 9385 2000 Email: [email protected] Telegraph: UNITECH, SYDNEY Telex: AA28054 http://www.unsw.edu.au Designed and published by Publishing and Printing Services, The University of New South Wales Printed by Sydney Allen Printers Pty Ltd ISSN 1323-7861 Contents Welcome 1 Changes to Academic Programs In 2000 3 Calendar of Dates 5 Staff 7 Handbook Guide 9 Faculty Information 11 General Faculty Information and Assistance 11 Faculty of Law Enrolment Procedures 11 Guidelines for Maximum Workload 11 Full-time Status 11 Part-time Status 11 Assessment of Student Progress 11 General Education Program 11 Professional Associates 12 Prizes 12 Advanced Standing 12 Cross Institutional Studies and Exchange Programs 12 Financial Assistance to Students 12 Commitment to Equal Opportunity In Education 13 Equal Opportunity in Education Policy Statement 13 Special Government Policies -

Women and Gender in the Royal Commission Into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody

Missing Subjects: Women and Gender in The Royal Commission Into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody Author Marchetti, Elena Maria Published 2005 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Criminology and Criminal Justice DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/335 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366882 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au MISSING SUBJECTS: WOMEN AND GENDER IN THE ROYAL COMMISSION INTO ABORIGINAL DEATHS IN CUSTODY Elena Maria Marchetti BCom LLB (Hons) LLM School of Criminology and Criminal Justice Faculty of Arts Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2005 ABSTRACT Although the Australian Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADIC) tabled its National Report over a decade ago, its 339 recommendations are still used to steer Indigenous justice policy. The inquiry is viewed by many policy makers and scholars as an important source of knowledge regarding the post-colonial lives of Indigenous people. It began as an investigation into Indigenous deaths in custody, but its scope was later broadened to encompass a wide range of matters affecting Indigenous Australians. There have been numerous criticisms made about the way the investigation was conducted and about the effectiveness and appropriateness of the recommendations made. Of particular relevance to this thesis are those criticisms that have highlighted the failure of the RCIADIC to consider the problems confronting Indigenous women. It has been claimed that although problems such as family violence and the sexual abuse of Indigenous women by police were acknowledged by both the RCIADIC and other scholars as having a significant impact upon the lives of Indigenous women, the RCIADIC failed to address these and other gender-specific problems. -

STOLEN GENERATIONS’ REPORT by RON BRUNTON

BETRAYING Backgrounder THE VICTIMS THE ‘STOLEN GENERATIONS’ REPORT by RON BRUNTON The seriousness of the ‘stolen generations’ issue should not be underestimated, and Aborigines are fully entitled to demand an acknowledgement of the wrongs that many of them suffered at the hands of various authorities. But both those who were wronged and the nation as a whole are also entitled to an honest and rigorous assessment of the past. This should have been the task of the ‘stolen generations’ inquiry. Unfortunately, however, the Inquiry’s report, Bringing Them Home, is one of the most intellectually and morally irresponsible official documents produced in recent years. In this Backgrounder, Ron Brunton carefully examines a number of matters covered by the report, such as the representativeness of the cases it discussed, its comparison of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal child removals, and its claim that the removal of Aboriginal children constituted ‘genocide’. He shows how the report is fatally compromised by serious failings. Amongst many others, these failings include omitting crucial evidence, misrepresenting important sources, making assertions that are factually wrong or highly questionable, applying contradictory principles at different times so as to make the worst possible case against Australia, and confusing different circumstances under which removals occurred in order to give the impression that nearly all separations were ‘forced’. February 1998, Vol. 10/1, rrp $10.00 BETRAYING THE VICTIMS: THE ‘STOLEN GENERATIONS’ REPORT bitterness that other Australians need to comprehend INTRODUCTION and overcome. A proper recognition of the injustices that Aborigi- nes suffered is not just a matter of creating opportuni- ties for reparations, despite the emphasis that the Bring- The Inquiry and its background ing Them Home report places on monetary compensa- Bringing Them Home, the report of the National Inquiry tion (for example, pages 302–313; Recommendations into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Is- 14–20). -

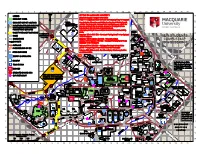

Campus Map New Students 2016 Session 1

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 A A B B C C D D NEW STUDENTS E CAMPUS MAP E 2016 SESSION 1 F F G G H H J J BIKE K HUB K L L BIKE HUB M M N N O O P BIKE P HUB Q Q R R S S T T U U V V W W 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 LOCATION GUIDE Telephone Switchboard: +61 2 9850 7111 General Email: [email protected] Web Site: mq.edu.au LOCATION BUILDING REF Cognitive Science S2.6 T14 ART GALLERY & MUSEUMS Graduation Unit C8A L3 N18 Emergency & First C1A S17 Institute of Early Childhood X5B L3 N10 Art Gallery E11A L1 H20 Higher Degree Research C5C L3 O17 Aid 9850 9999 Office Linguistics C5A L5 P16 Australian History Museum W6A 126 O12 Security & C1A S17 Hospital & Allied Health F8A L27 Psychology C3A L5 Q16 Biological Sciences Museum E8B L23 services Information Learning & Teaching Centre C3B P17 Student Connect C7A N15 School of Education C3A L8 Q16 Herbarium E8C L1 M23 Library C3C Q17 Macquarie E-Learning W6B 152 N12 IEC Art Collection X5B N10 Centre of Excellence Macquarie International E3A Q20 FACULTY OF ARTS W6A L1 O12 Lachlan Macquarie Room C3C Q17 Macquarie ICT C5B L0 O16 Arts Student Centre W6A L1 O12 Medical Centre & Clinic F10A L3 K26 Innovations Centre Museum of Ancient Cultures X5B 331 N10 Macquarie University X5A O9 METS (Macquarie F9B K24 Sporting Hall of Fame W10A J12 Engineering Technical Ancient History W6A 540 O12 Special Education Museum Services) Anthropology W6A 615 O12 MUSRA C10A L1 K17 FACULTY OF MEDICINE & HEALTH SCIENCES English -

Undergraduate Courses2020

Undergraduate courses 2020 When your potential is multiplied by a university built for collaboration, anything can be achieved. That’s YOU to the power of us At Macquarie, we have discovered the human equation for success. By knocking down the walls between departments, and uniting the powerhouses of research and industry, human collaboration can flourish. This is the exponential power of our collective, where potential is multiplied by a campus and curriculum designed to foster collaboration for the benefit of everyone. Because we believe when we all work together, we multiply our ability to achieve remarkable things. That’s YOU to the power of us 4 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE COURSES 2020 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE COURSES 2020 5 Contents MACQUARIE AT A GLANCE 6 MAKE YOUR DREAM CAREER A REALITY 10 PACE (PROFESSIONAL AND 12 COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT) GLOBAL LEADERSHIP PROGRAM 14 STUDENT EXCHANGE PROGRAM 16 GLOBAL LEADERS ON THE DOORSTEP 20 OUR CAMPUS 22 SUPPORT, SERVICES AND FLEXIBILITY 24 STUDENT ACCOMMODATION 26 MACQUARIE ENTRY 30 ADJUSTMENT FACTORS 32 CASH IN WITH A SCHOLARSHIP 34 WHAT CAN I STUDY? 36 FEES AND OTHER COSTS 40 HOW TO APPLY 41 LEARN THE LINGO 42 COURSES MADE BY (YOU)us 44 2019 CALENDAR OF EVENTS 106 Questions? Ask us anything … FUTURE STUDENTS Degrees, entry requirements, fees and general enquiries: • chat live by clicking on the chat icon on any degree page • ask us a question at [email protected] • call us on (02) 9850 6767. 6 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE COURSES 2020 MACQUARIE UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE -

Annual Report 2017

7 I • I The Australasian Institute of Judicial Administration Incorporated Annual Report 201 for the year ended 30 June 2017 PATRONS The Hon Robert French AC His Honour Judge Peter Johnstone Chief Justice of Australia (until February 2017) Children’s Court of New South Wales The Hon Susan Kiefel AC The Hon Justice Susan Kenny Chief Justice of Australia (from February 2017) Federal Court of Australia The Rt Hon Dame Sian Elias GNZM The Hon Justice Duncan Kerr Chev LH Chief Justice of New Zealand Federal Court of Australia COUNCIL Mr Adam Kimber SC President Director of Public Prosecutions, South Australia The Hon Justice Robert Mazza Supreme Court of Western Australia Professor Kathy Mack Flinders University, South Australia Deputy President/President Elect The Hon Justice Bob Gotterson AO Mr Greg Manning Court of Appeal, Queensland Attorney-General’s Department, Canberra Deputy President His Honour Judge Nicholoas Manousaridis Mr Laurie Glanfield AM Federal Circuit Court of Australia New South Wales Mr Dan O’Gorman SC Members Barrister, Queensland The Hon Justice Murray Aldridge Family Court of Australia Deputy Chief Magistrate Jelena Popovic Magistrates’ Court, Victoria Mr Iain Anderson Attorney General’s Department, ACT The Hon Justice Steven Rares Federal Court of Australia Justice Jenny Blokland Supreme Court of the Northern Territory The Hon Justice Richard Refshauge Supreme Court of the Australian Capital Territory Hon Justice Malcolm Blue Supreme Court of South Australia Ms Jane Reynolds Family Court of Australia and Federal Court -

Dialogue and Indigenous Policy in Australia

Dialogue and Indigenous Policy in Australia Darryl Cronin A thesis in fulfilment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Social Policy Research Centre Faculty of Arts & Social Sciences September 2015 ABSTRACT My thesis examines whether dialogue is useful for negotiating Indigenous rights and solving intercultural conflict over Indigenous claims for recognition within Australia. As a social and political practice, dialogue has been put forward as a method for identifying and solving difficult problems and for promoting processes of understanding and accommodation. Dialogue in a genuine form has never been attempted with Indigenous people in Australia. Australian constitutionalism is unable to resolve Indigenous claims for recognition because there is no practice of dialogue in Indigenous policy. A key barrier in that regard is the underlying colonial assumptions about Indigenous people and their cultures which have accumulated in various ways over the course of history. I examine where these assumptions about Indigenous people originate and demonstrate how they have become barriers to dialogue between Indigenous people and governments. I investigate historical and contemporary episodes where Indigenous people have challenged those assumptions through their claims for recognition. Indigenous people have attempted to engage in dialogue with governments over their claims for recognition but these attempts have largely been rejected on the basis of those assumptions. There is potential for dialogue in Australia however genuine dialogue between Indigenous people and the Australian state is impossible under a colonial relationship. A genuine dialogue must first repudiate colonial and contemporary assumptions and attitudes about Indigenous people. It must also deconstruct the existing colonial relationship between Indigenous people and government. -

Water Governance and Planing

Faculty of Law SPECIALISTS IN WATER GOVERNANCE AND PLANNING We undertake law and policy design optimisation for The UNSW Faculty of Law has a highly regarded governing water extraction, water planning, water international reputation in water law, water governance pollution, natural resource use, sanitation and water and planning. related impacts of unconventional gas. UNSW Law is one of the world’s top ranking Law Schools OUR PARTNERS (13th in the QS World University Rankings 2016). It is at UNSW Law collaborates extensively with university the cutting edge of interdisciplinary water law and researchers both internationally and within Australia. In governance research that leads to real change in water addition to this, extensive collaboration with government policy and water law. and industry is a hallmark of UNSW Law. THE TOOLS OF OUR TRADE ACADEMIC EXCELLENCE Our Faculty has large, state-of-the-art resources that include: Our key academic disciplines include: water law and policy, regulation and governance, natural resource • A team of highly experienced professional staff management, property law and environmental law. comprising academics, lawyers, researchers, postgraduate students and support staff. KEYSTONE PROJECTS • A range of leading legal research, advocacy and education centres, including Andrew & Renata Kaldor • Decentralised Groundwater Management: Centre for International Refugee Law; Australian Comparative Lessons from France and Australia Human Rights Centre; Centre for International • Revitalising Collaborative Water Governance: Finance & Regulation; Centre for Law, Markets & Lessons from Water Planning in Australia Regulation; China International Business & Economic • Compliance and enforcement in non-urban water Law Initiative (CIBEL); Cyberspace Law & Policy extraction in NSW (with DPI Water) Community; Gilbert + Tobin Centre of Public Law and • Trans-jurisdictional Water Law and Governance the Indigenous Law Centre.