A Functional Interpretation of Pottery from Batan Island, Philippines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WAR AND RESISTANCE: THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida, History Department What happened in the Philippine Islands between the surrender of Allied forces in May 1942 and MacArthur’s return in October 1944? Existing historiography is fragmentary and incomplete. Memoirs suffer from limited points of view and personal biases. No academic study has examined the Filipino resistance with a critical and interdisciplinary approach. No comprehensive narrative has yet captured the fighting by 260,000 guerrillas in 277 units across the archipelago. This dissertation begins with the political, economic, social and cultural history of Philippine guerrilla warfare. The diverse Islands connected only through kinship networks. The Americans reluctantly held the Islands against rising Japanese imperial interests and Filipino desires for independence and social justice. World War II revealed the inadequacy of MacArthur’s plans to defend the Islands. The General tepidly prepared for guerrilla operations while Filipinos spontaneously rose in armed resistance. After his departure, the chaotic mix of guerrilla groups were left on their own to battle the Japanese and each other. While guerrilla leaders vied for local power, several obtained radios to contact MacArthur and his headquarters sent submarine-delivered agents with supplies and radios that tie these groups into a united framework. MacArthur’s promise to return kept the resistance alive and dependent on the United States. The repercussions for social revolution would be fatal but the Filipinos’ shared sacrifice revitalized national consciousness and created a sense of deserved nationhood. The guerrillas played a key role in enabling MacArthur’s return. -

Sustainable Agricultural Production Systems for Food Security in a Changing Climate in Batanes, Philippines

Journal of Developments in Sustainable Agriculture 9: 111-119 (2014) Sustainable Agricultural Production Systems for Food Security in a Changing Climate in Batanes, Philippines Lucille Elna P. de Guzman1, Oscar B. Zamora1, 2,JoanPaulineP.Talubo3* and Cesar Doroteo V. Hostallero4 1 Crop Science Cluster, College of Agriculture, University of the Philippines Los Baños 2 Office of the Vice-Chancellor for Academic Affairs, University of the Philippines Los Baños 3 Department of Community and Environmental Resource Planning, College of Human Ecology, University of the Philippines Los Baños 4 Office of the Provincial Agriculturist, Basco, Batanes, Philippines Climate change could have significant impacts in the Philippines on large sections of the population who are poor and vulnerable, especially those who live in areas prone to coastal storms, drought and sea level rise. The sectors mostly affected by climate change are agriculture and food security because of the risk of low productivity due to increasing temperature, drought, and increasing frequency and intensity of rainfall that brings about floods and land- slides. Located in the northernmost tip of the country, the Batanes group of islands lies on the country’s typhoon belt. Because of vulnerability and isolation from the rest of the archipelago, the Ivatans have developed self-sufficient, organic and climate-resilient crop production systems. This paper presents the indigenous crop production systems that have made the Ivatans food self-sufficient despite vulnerability of their agroecosystem. A typical Ivatan farmer owns 3-7 parcels of land. Each parcel has an average size of 300-500 m2.Farmers practice a rootcrop-based multiple cropping system with specific spatial arrangements of corn (Zea mays), gabi (Colocasia esculenta), yam (Dioscorea alata) and tugui (Dioscorea esculenta), using corn stover, hardwood trees or a local reed called viyawu (Miscanthus sp.) as trellis. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE Highlights of the Region II (Cagayan Valley) Population 2020 Census of Population and Housing (2020 CPH) Date of Release: 20 August 2021 Reference No. 2021-317 • The population of Region II - Cagayan Valley as of 01 May 2020 is 3,685,744 based on the 2020 Census of Population and Housing (2020 CPH). This accounts for about 3.38 percent of the Philippine population in 2020. • The 2020 population of the region is higher by 234,334 from the population of 3.45 million in 2015, and 456,581 more than the population of 3.23 million in 2010. Moreover, it is higher by 872,585 compared with the population of 2.81 million in 2000. (Table 1) Table 1. Total Population Based on Various Censuses: Region II - Cagayan Valley Census Year Census Reference Date Total Population 2000 May 1, 2000 2,813,159 2010 May 1, 2010 3,229,163 2015 August 1, 2015 3,451,410 2020 May 1, 2020 3,685,744 Source: Philippine Statistics Authority • The population of Region II increased by 1.39 percent annually from 2015 to 2020. By comparison, the rate at which the population of the region grew from 2010 to 2015 was lower at 1.27 percent. (Table 2) Table 2. Annual Population Growth Rate: Region II - Cagayan Valley (Based on Various Censuses) Intercensal Period Annual Population Growth Rate (%) 2000 to 2010 1.39 2010 to 2015 1.27 2015 to 2020 1.39 Source: Philippine Statistics Authority PSA Complex, East Avenue, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines 1101 Telephone: (632) 8938-5267 www.psa.gov.ph • Among the five provinces comprising Region II, Isabela had the biggest population in 2020 with 1,697,050 persons, followed by Cagayan with 1,268,603 persons, Nueva Vizcaya with 497,432 persons, and Quirino with 203,828 persons. -

Sitecode Year Region Penro Cenro Province

***Data is based on submitted maps per region as of January 8, 2018. AREA IN SITECODE YEAR REGION PENRO CENRO PROVINCE MUNICIPALITY BARANGAY DISTRICT NAME OF ORGANIZATION SPECIES COMMODITY COMPONENT TENURE HECTARES 14- 023126-0084-0200 2014 II Isabela Roxas Isabela Mallig Manano II 200.02 Villa Corazon Environmental Greening Association Narra, Rain Tree, Gmelina, Mahogany, Cacao,Calamansi and Tamarind Timber Refo, Agroforestry Untenured 14- 023126-0085-0050 2014 II Isabela Roxas Isabela Mallig Manano II 50.00 Villa Corazon Environmental Greening Association Narra, Rain Tree, Gmelina, Mahogany, Cacao,Calamansi and Tamarind Timber Refo, Agroforestry Untenured 14- 023126-0086-0070 2014 II Isabela Roxas Isabela Quezon Manga II 70.01 Quezon-Tabuk Greeners Association Inc. Narra, Rain Tree, Gmelina, Mahogany Timber Refo, Agroforestry Untenured 14- 023126-0087-0130 2014 II Isabela Roxas Isabela Quezon Santos II 130.32 Bantay Ti Banbantay Narra, Rain Tree, Gmelina, Mahogany, and Cacao Timber Refo, Agroforestry Untenured 14-020900-0001-0010 2014 II Batanes Batanes Sabtang Sinakan Lone District 10.03 LGU Sabtang Mabolo, Malugai, Antipolo, Bitaog, Talisay, Arius Timber Reforestation Protected Area 14-020900-0002-0018 2014 II Batanes Batanes Sabtang Chavayan Lone District 18.22 LGU Sabtang Mabolo, Malugai, Antipolo, Bitaog, Talisay, Arius Timber Reforestation Protected Area 14-020900-0003-0051 2014 II Batanes Batanes Itbayat Raele Lone District 51.43 LGU Itbayat Mabolo, Malugai, Antipolo, Bitaog, Talisay, Arius Timber Reforestation Protected Area 14-020900-0004-0036 2014 II Batanes Batanes Itbayat Raele Lone District 36.34 LGU Itbayat Mabolo, Malugai, Antipolo, Bitaog, Talisay, Arius Timber Reforestation Protected Area 14-020900-0005-0023 2014 II Batanes Batanes Itbayat Raele Lone District 22.99 Modesta Malupa Mabolo, Malugai, Antipolo, Bitaog, Talisay, Arius Timber Reforestation Protected Area 14-021502-0006-0270 2014 II Cagayan Alcala Cagayan Baggao Sta. -

Ivatan Indigenous Knowledge, Classificatory Systems, and Risk Reduction Practices

Journal of Nature Studies 18(1): 76-96 Online ISSN: 2244-5226 IVATAN INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE, CLASSIFICATORY SYSTEMS, AND RISK REDUCTION PRACTICES Rolando C. Esteban1* and Edwin A. Valientes1 1 University of the Philippines Diliman *Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT – The paper aims to offer an emic perspective of Ivatan indigenous knowledge, classificatory systems, and risk reduction practices. It is based on primary data gathered through fieldwork in Basco and Ivana in Batan Island and in Chavayan in Sabtang Island in 2011-13 and 2017. Classificatory systems are ways of recognizing, differentiating, understanding, and categorizing ideas, objects, and practices. Ivatan classificatory systems are ecological and agrometeorological in nature. The distinction that they make between good and bad weather and good and bad times manifest binary, oppositional logic. Notions of bad weather and bad times are emphasized more than the good ones because of the risks involved. They are products of observations and experiences evolved over time in an environment that is prone to disasters because of its geomorphology, location, and practices. They are used in everyday life and during disasters, and always adapted to new knowledge and practices for survival. Keywords: classificatory system, disaster, emic perspective, indigenous knowledge, risk reduction practices INTRODUCTION Knowledge is either modem or indigenous. Modern denotes ‘scientific’ based on Western epistemology (Collins, 1983), while indigenous denotes ‘traditional’, ‘local’, and ‘environmental’ (Anuradha, 1998; Briggs and Sharp, 2004; Chesterfield and Ruddle, 1979; Morris, 2010; Tong, 2010). Thus, indigenous knowledge (IK) is synonymous with traditional knowledge (Anuradha, 1998; Brodt, 2001; Doxtater, 2004; Ellen and Harris, 1997; Sillitoe, 1998), local knowledge (Morris, 2010; Palmer and Wadley, 2007), and environmental knowledge (Ellen and Harris, 1997; Hunn et al., 2003). -

Bullet Train of Non-Linear Internal Waves from Luzon Strait C

BULLET TRAIN OF NON-LINEAR INTERNAL WAVES FROM LUZON STRAIT C-T Liu, R. Pinkel, M-K Hsu, R-S Tseng, Y-H Wang, J.M. Klymak, H-W Chen, C. Villanoy, L. David, Y. Yang, C-H Nan, Y-J Chyou, C-W Lee and Antony K. Liu In the northeastern South China Sea, a series of fast moving (about 2.9 m/s) non-linear internal waves (NLIWs) emanated westward from the Luzon Strait. Their propagation speed is faster than NLIWs previously observed in the world oceans, their amplitude reached 140 m or more, and are the largest free propagating NLIWs so far observed in the interior ocean. These NLIWs energized the top 1500 m of the water column, heaving it up and down in 20 min. Their associated energy density and energy flux are the largest observed to date. The exact source of these giant NLIWs is still under study and to be determined. BACKGROUND: Non-Linear Internal Waves (NLIWs) are often found in shelf regions. They are typically thought to be generated by tidal currents over steep topography (sill, seamount, shelf break, etc.) or sometimes by the instability of current shears. An ERS-1 SAR image of a non-linear internal waves (NLIW) near Luzon Strait (LS) in 1995/6/16 (http://sol.oc.ntu.edu.tw/IW/1995/ERS1.htm) showed quite different features than NLIW images nearer Taiwan (Liu et al., 1994). Existing theories and experience were insufficient to explain the location, shape and size of NLIW in that SAR image. To the west of LS, the HengChun Ridge (HCR) connects the southern tip of Taiwan to the continental shelf north of Luzon Island; Batan Islands and Babuyan Islands spread east of HCR. -

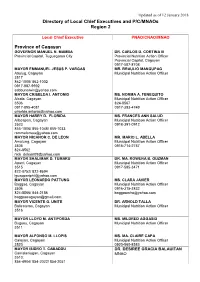

Directory of Local Chief Executives and P/C/Mnaos Region 2

Updated as of 12 January 2018 Directory of Local Chief Executives and P/C/MNAOs Region 2 Local Chief Executive PNAO/CNAO/MNAO Province of Cagayan GOVERNOR MANUEL N. MAMBA DR. CARLOS D. CORTINA III Provincial Capitol, Tuguegarao City Provincial Nutrition Action Officer Provincial Capitol, Cagayan 0917-587-8708 MAYOR EMMANUEL JESUS P. VARGAS MR. BRAULIO MANGUPAG Abulug, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3517 862-1008/ 862-1002 0917-887-9992 [email protected] MAYOR CRISELDA I. ANTONIO MS. NORMA A. FENEQUITO Alcala, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3506 824-8567 0917-895-4081 0917-393-4749 [email protected] MAYOR HARRY D. FLORIDA MS. FRANCES ANN SALUD Allacapan, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3523 0918-391-0912 855-1006/ 855-1048/ 855-1033 [email protected] MAYOR NICANOR C. DE LEON MR. MARIO L. ABELLA Amulung, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3505 0915-714-2757 824-8562 [email protected] MAYOR SHALIMAR D. TUMARU DR. MA. ROWENA B. GUZMAN Aparri, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3515 0917-585-3471 822-8752/ 822-8694 [email protected] MAYOR LEONARDO PATTUNG MS. CLARA JAVIER Baggao, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3506 0916-315-3832 824-8566/ 844-2186 [email protected] [email protected] MAYOR VICENTE G. UNITE DR. ARNOLD TALLA Ballesteros, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3516 MAYOR LLOYD M. ANTIPORDA MS. MILDRED AGGASID Buguey, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3511 MAYOR ALFONSO M. LLOPIS MS. MA. CLAIRE CAPA Calayan, Cagayan Municipal Nutrition Action Officer 3520 0920-560-8583 MAYOR ISIDRO T. CABADDU DR. DESIREE GRACIA BALAUITAN Camalaniugan, Cagayan MNAO 3510; 854-4904/ 854-2022/ 854-2051 Updated as of 12 January 2018 MAYOR CELIA T. -

Archaeological Investigations at Savidug, Sabtang Island

4 Archaeological Investigations at Savidug, Sabtang Island Peter Bellwood and Eusebio Dizon This chapter is focused on the site complex near Savidug village, roughly half way down the eastern coast of Sabtang Island, facing across a sea passage to the southwestern coastline of Batan. The Sabtang site complex includes an impressive ijang of sheer volcanic rock, which we surveyed. A sand dune to the north, close to Savidug village itself, contained two distinct archaeological phases separated by about a millennium of non-settlement in the site. We also excavated another small late prehistoric shell midden at Pamayan, inland from Savidug village. In 2002, brief visits for reconnaissance purposes by the Asian Fore-Arc Project were made to Sabtang and Ivuhos Islands (Bellwood et al. 2003). As a result, one week was spent on Sabtang in 2003, during which time a plane-table survey and test excavations were carried out at Savidug ijang, and the Pamayan shell midden at the back of Savidug village was test-excavated. The location of Savidug village is indicated on Fig. 4.1, half way down the eastern coast of Sabtang and facing the southern end of Batan, 5 km across the ocean passage to the northeast. In 2006, test-excavation was undertaken at the Savidug Dune Site (Nadapis), which yielded a sequence extending back 3000 years incorporating two separate phases of human activity commencing with circle stamped pottery dated to c.1000 BC and very similar to that at Anaro on Itbayat and Sunget on Batan. In 2007, Savidug Dune Site was subjected to further excavation for 3 weeks, resulting in the recovery of several large burial jars, Taiwan nephrite, and a more thorough understanding of the nature of the whole site. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BATANES

2010 Census of Population and Housing Batanes Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BATANES 16,604 BASCO (Capital) 7,907 Ihubok II (Kayvaluganan) 2,103 Ihubok I (Kaychanarianan) 1,665 San Antonio 1,772 San Joaquin 392 Chanarian 334 Kayhuvokan 1,641 ITBAYAT 2,988 Raele 442 San Rafael (Idiang) 789 Santa Lucia (Kauhauhasan) 478 Santa Maria (Marapuy) 438 Santa Rosa (Kaynatuan) 841 IVANA 1,249 Radiwan 368 Salagao 319 San Vicente (Igang) 230 Tuhel (Pob.) 332 MAHATAO 1,583 Hanib 372 Kaumbakan 483 Panatayan 416 Uvoy (Pob.) 312 SABTANG 1,637 Chavayan 169 Malakdang (Pob.) 245 Nakanmuan 134 Savidug 190 Sinakan (Pob.) 552 Sumnanga 347 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Batanes Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population UYUGAN 1,240 Kayvaluganan (Pob.) 324 Imnajbu 159 Itbud 463 Kayuganan (Pob.) 294 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and Housing Cagayan Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population CAGAYAN 1,124,773 ABULUG 30,675 Alinunu 1,269 Bagu 1,774 Banguian 1,778 Calog Norte 934 Calog Sur 2,309 Canayun 1,328 Centro (Pob.) 2,400 Dana-Ili 1,201 Guiddam 3,084 Libertad 3,219 Lucban 2,646 Pinili 683 Santa Filomena 1,053 Santo Tomas 884 Siguiran 1,258 Simayung 1,321 Sirit 792 San Agustin 771 San Julian 627 Santa -

Final Report

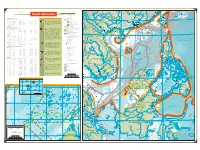

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS AND HIGHWAYS THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES THE FEASIBILITY STUDY OF THE FLOOD CONTROL PROJECT FOR THE LOWER CAGAYAN RIVER IN THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES FINAL REPORT VOLUME III-2 SUPPORTING REPORT ANNEX VII WATERSHED MANAGEMENT ANNEX VIII LAND USE ANNEX IX COST ESTIMATE ANNEX X PROJECT EVALUATION ANNEX XI INSTITUTION ANNEX XII TRANSFER OF TECHNOLOGY FEBRUARY 2002 NIPPON KOEI CO., LTD. NIKKEN Consultants, Inc. SSS JR 02- 07 List of Volumes Volume I : Executive Summary Volume II : Main Report Volume III-1 : Supporting Report Annex I : Socio-economy Annex II : Topography Annex III : Geology Annex IV : Meteo-hydrology Annex V : Environment Annex VI : Flood Control Volume III-2 : Supporting Report Annex VII : Watershed Management Annex VIII : Land Use Annex IX : Cost Estimate Annex X : Project Evaluation Annex XI : Institution Annex XII : Transfer of Technology Volume III-3 : Supporting Report Drawings Volume IV : Data Book The cost estimate is based on the price level and exchange rate of June 2001. The exchange rate is: US$1.00 = PHP50.0 = ¥120.0 Cagayan River N Basin PHILIPPINE SEA Babuyan Channel Apayao-Abulug ISIP Santa Ana Camalaniugan Dike LUZON SEA MabangucDike Aparri Agro-industry Development / Babuyan Channel by CEZA Catugan Dike Magapit PIS (CIADP) Lallo West PIP MINDANAO SEA Zinundungan IEP Lal-lo Dike Lal-lo KEY MAP Lasam Dike Evacuation System (FFWS, Magapit Gattaran Dike Alcala Amulung Nassiping PIP evacuation center), Resettlement, West PIP Dummon River Supporting Measures, CAGAYAN Reforestation, and Sabo Works Nassiping are also included in the Sto. Niño PIP Tupang Pared River Nassiping Dike Alcala Reviewed Master Plan. -

Spratly Islands

R i 120 110 u T4-Y5 o Ganzhou Fuqing n h Chenzhou g Haitan S T2- J o Dao Daojiang g T3 S i a n Putian a i a n X g i Chi-lung- Chuxiong g n J 21 T6 D Kunming a i Xingyi Chang’an o Licheng Xiuyu Sha Lung shih O J a T n Guilin T O N pa Longyan T7 Keelung n Qinglanshan H Na N Lecheng T8 T1 - S A an A p Quanzhou 22 T'ao-yüan Taipei M an T22 I L Ji S H Zhongshu a * h South China Sea ng Hechi Lo-tung Yonaguni- I MIYAKO-RETTO S K Hsin-chu- m c Yuxi Shaoguan i jima S A T21 a I n shih Suao l ) Zhangzhou Xiamen c e T20 n r g e Liuzhou Babu s a n U T Taichung e a Quemoy p i Meizhou n i Y o J YAEYAMA-RETTO a h J t n J i Taiwan C L Yingcheng K China a a Sui'an ( o i 23 n g u H U h g n g Fuxing T'ai- a s e i n Strait Claimed Straight Baselines Kaiyuan H ia Hua-lien Y - Claims in the Paracel and Spratly Islands Bose J Mai-Liao chung-shih i Q J R i Maritime Lines u i g T9 Y h e n e o s ia o Dongshan CHINA u g B D s Tropic of Cancer J Hon n Qingyuan Tropic of Cancer Established maritime boundary ian J Chaozhou Makung n Declaration of the People’s Republic of China on the Baseline of the Territorial Sea, May 15, 1996 g i Pingnan Heyuan PESCADORES Taiwan a Xicheng an Wuzhou 21 25° 25.8' 00" N 119° 56.3' 00" E 31 21° 27.7' 00" N 112° 21.5' 00" E 41 18° 14.6' 00" N 109° 07.6' 00" E While Bandar Seri Begawan has not articulated claims to reefs in the South g Jieyang Chaozhou 24 T19 N BRUNEI Claim line Kaihua T10- Hsi-yü-p’ing Chia-i 22 24° 58.6' 00" N 119° 28.7' 00" E 32 19° 58.5' 00" N 111° 16.4' 00" E 42 18° 19.3' 00" N 108° 57.1' 00" E China Sea (SCS), since 1985 the Sultanate has claimed a continental shelf Xinjing Guiping Xu Shantou T11 Yü Luxu n Jiang T12 23 24° 09.7' 00" N 118° 14.2' 00" E 33 19° 53.0' 00" N 111° 12.8' 00" E 43 18° 30.2' 00" N 108° 41.3' 00" E X Puning T13 that extends beyond these features to a hypothetical median with Vietnam.