A Rhetorical Analysis of Annalise Keating's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Re-Mixing Old Character Tropes on Screen: Kerry Washington, Viola Davis, and the New Femininity by Melina Kristine Dabney A

Re-mixing Old Character Tropes on Screen: Kerry Washington, Viola Davis, and the New Femininity By Melina Kristine Dabney A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Film Studies 2017 This thesis entitled: Re-mixing Old Character Tropes on Screen: Kerry Washington, Viola Davis, and the new Femininity written by Melina Kristine Dabney has been approved for the Department of Film Studies ________________________________________________ (Melinda Barlow, Ph.D., Committee Chair) ________________________________________________ (Suranjan Ganguly, Ph.D., Committee Member) ________________________________________________ (Reiland Rabaka, Ph.D., Committee Member) Date: The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. Dabney, Melina Kristine (BA/MA Film Studies) Re-mixing Old Character Tropes on Screen: Kerry Washington, Viola Davis, and the New Femininity Thesis directed by Professor Melinda Barlow While there is a substantial amount of scholarship on the depiction of African American women in film and television, this thesis exposes the new formations of African American femininity on screen. African American women have consistently resisted, challenged, submitted to, and remixed racial myths and sexual stereotypes existing in American cinema and television programming. Mainstream film and television practices significantly contribute to the reinforcement of old stereotypes in contemporary black women characters. However, based on the efforts of African American producers like Shonda Rhimes, who has attempted to insert more realistic renderings of African American women in her recent television shows, black women’s representation is undergoing yet another shift in contemporary media. -

Black Women, Natural Hair, and New Media (Re)Negotiations of Beauty

“IT’S THE FEELINGS I WEAR”: BLACK WOMEN, NATURAL HAIR, AND NEW MEDIA (RE)NEGOTIATIONS OF BEAUTY By Kristin Denise Rowe A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of African American and African Studies—Doctor of Philosophy 2019 ABSTRACT “IT’S THE FEELINGS I WEAR”: BLACK WOMEN, NATURAL HAIR, AND NEW MEDIA (RE)NEGOTIATIONS OF BEAUTY By Kristin Denise Rowe At the intersection of social media, a trend in organic products, and an interest in do-it-yourself culture, the late 2000s opened a space for many Black American women to stop chemically straightening their hair via “relaxers” and begin to wear their hair natural—resulting in an Internet-based cultural phenomenon known as the “natural hair movement.” Within this context, conversations around beauty standards, hair politics, and Black women’s embodiment have flourished within the public sphere, largely through YouTube, social media, and websites. My project maps these conversations, by exploring contemporary expressions of Black women’s natural hair within cultural production. Using textual and content analysis, I investigate various sites of inquiry: natural hair product advertisements and internet representations, as well as the ways hair texture is evoked in recent song lyrics, filmic scenes, and non- fiction prose by Black women. Each of these “hair moments” offers a complex articulation of the ways Black women experience, share, and negotiate the socio-historically fraught terrain that is racialized body politics -

How to Get Away with Colour: Colour-Blindness and the Myth of a Postracial America in American Television Series

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title How to get away with colour: colour-blindness and the myth of a postracial America in American television series Author(s) Martens, Emiel; Póvoa, Débora Publication date 2017 Original citation Martens, E. and Póvoa, D. (2017) 'How to get away with colour: colour- blindness and the myth of a postracial America in American television series', Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 13, 117-134. Type of publication Article (peer-reviewed) Link to publisher's http://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue13/13_7Article_MartensPovoa.p version df Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2017, The Author(s) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/6032 from Downloaded on 2021-09-24T05:10:11Z How to Get Away with Colour: Colour- Blindness and the Myth of a Postracial America in American Television Series Emiel Martens and Débora Povoa Abstract: The popular American television series How to Get Away with Murder (2014) seems to challenge the long history of stereotypical roles assigned to racial minorities in American media by choosing a multiracial cast to impersonate characters that, while having different racial backgrounds, share a similar socio-economic status and have multidimensional personalities that distance them from the common stereotypes. However, although it has been praised for its portrayal of racial diversity, the series operates within a problematic logic of racial colour-blindness, disconnecting the main characters from any sign of racial specificity and creating a fictional world in which racism is no longer part of American society. -

Examining Interracial Relationships in Shondaland

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 5-2017 Gender in Black and White: Examining Interracial Relationships in ShondaLand Caitlin V. Downing Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Downing, Caitlin V., "Gender in Black and White: Examining Interracial Relationships in ShondaLand" (2017). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 110. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/110 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gender in Black and White: Examining Interracial Relationships in ShondaLand By Caitlin Downing Prepared for Dr. Esch English Department Salve Regina University May 8, 2017 Downing 1 Gender in Black and White: Examining Interracial Relationships in ShondaLand ABSTRACT: Shonda Rhimes has been credited for crafting progressive television dramas that attract millions of viewers. Scholars have found that through the use of tactics like colorblind casting, Rhimes unintentionally creates problematic relationships between characters. Focusing on production techniques and dialogue, this paper examines episodes from two of her most popular shows, How To Get Away With Murder and Scandal. This paper argues that while the shows pursue progressive material, the shows present African-American female characters that require partners. Further, both white male characters negatively influence the women’s independence. -

87Th Academy Awards Reminder List

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 87TH ACADEMY AWARDS ABOUT LAST NIGHT Actors: Kevin Hart. Michael Ealy. Christopher McDonald. Adam Rodriguez. Joe Lo Truglio. Terrell Owens. David Greenman. Bryan Callen. Paul Quinn. James McAndrew. Actresses: Regina Hall. Joy Bryant. Paula Patton. Catherine Shu. Hailey Boyle. Selita Ebanks. Jessica Lu. Krystal Harris. Kristin Slaysman. Tracey Graves. ABUSE OF WEAKNESS Actors: Kool Shen. Christophe Sermet. Ronald Leclercq. Actresses: Isabelle Huppert. Laurence Ursino. ADDICTED Actors: Boris Kodjoe. Tyson Beckford. William Levy. Actresses: Sharon Leal. Tasha Smith. Emayatzy Corinealdi. Kat Graham. AGE OF UPRISING: THE LEGEND OF MICHAEL KOHLHAAS Actors: Mads Mikkelsen. David Kross. Bruno Ganz. Denis Lavant. Paul Bartel. David Bennent. Swann Arlaud. Actresses: Mélusine Mayance. Delphine Chuillot. Roxane Duran. ALEXANDER AND THE TERRIBLE, HORRIBLE, NO GOOD, VERY BAD DAY Actors: Steve Carell. Ed Oxenbould. Dylan Minnette. Mekai Matthew Curtis. Lincoln Melcher. Reese Hartwig. Alex Desert. Rizwan Manji. Burn Gorman. Eric Edelstein. Actresses: Jennifer Garner. Kerris Dorsey. Jennifer Coolidge. Megan Mullally. Bella Thorne. Mary Mouser. Sidney Fullmer. Elise Vargas. Zoey Vargas. Toni Trucks. THE AMAZING CATFISH Actors: Alejandro Ramírez-Muñoz. Actresses: Ximena Ayala. Lisa Owen. Sonia Franco. Wendy Guillén. Andrea Baeza. THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN 2 Actors: Andrew Garfield. Jamie Foxx. Dane DeHaan. Colm Feore. Paul Giamatti. Campbell Scott. Marton Csokas. Louis Cancelmi. Max Charles. Actresses: Emma Stone. Felicity Jones. Sally Field. Embeth Davidtz. AMERICAN REVOLUTIONARY: THE EVOLUTION OF GRACE LEE BOGGS 87th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AMERICAN SNIPER Actors: Bradley Cooper. Luke Grimes. Jake McDorman. Cory Hardrict. Kevin Lacz. Navid Negahban. Keir O'Donnell. Troy Vincent. Brandon Salgado-Telis. -

A Content Analysis of Olivia Pope: How Scandal Reconfirms the Negative Stereotypes of Black Women

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2020 A content analysis of Olivia Pope: how scandal reconfirms the negative stereotypes of black women. Chelsy LeAnn Golder University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Golder, Chelsy LeAnn, "A content analysis of Olivia Pope: how scandal reconfirms the negative stereotypes of black women." (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3471. Retrieved from https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd/3471 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF OLIVIA POPE: HOW SCANDAL RECONFIRMS THE NEGATIVE STEREOTYPES OF BLACK WOMEN By Chelsy LeAnn Golder B.A., Northern Kentucky University, 2018 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Communication Department of Communication University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2020 A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF OLIVIA POPE: HOW SCANDAL RECONFIRMS THE NEGATIVE STEREOTYPES OF BLACK WOMEN By Chelsy LeAnn Golder B.A., Northern Kentucky University, 2018 A Thesis Approved on 4/17/2020 By the following Thesis Committee ______________________________ Dr. -

Annalise Keating's Portrayal As a Black Attorney Is the Real Scandal

UCLA National Black Law Journal Title Annalise Keating's Portrayal as a Black Attorney is the Real Scandal: Examining How the Use of Stereotypical Depictions of Black Women can Lead to the Formation of Implicit Biases Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6wd3d4gk Journal National Black Law Journal, 27(1) ISSN 0896-0194 Author Toms-Anthony, Shamar Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ANNALISE KEATING’S PORTRAYAL AS A BLACK ATTORNEY IS THE REAL SCANDAL: Examining How the Use of Stereotypical Depictions of Black Women Can Lead to the Formation of Implicit Biases Shamar Toms-Anthony* Abstract Law firms are struggling to increase the representation and retention of Black women, and Black women have reported feeling excluded, invisible, and a lack of support within law firms. In this Comment, I posit that ABC’s hit show “How to Get Away with Murder” over relies on traditional negative stereotypes about Black women. Annalise Keating, the show’s lead character, conforms to the stereotypes of the Jezebel, the Mammy, and the Angry Black Woman. Fur- ther, Keating’s representation as a Black female attorney is uniquely significant because historically Black women have done very little lawyering on the television screen. Thus, Keating’s representation as a Black female attorney on a show that has garnered upwards of twenty million viewers in a single episode is extremely influential, as it can have the effect of shaping audiences’ perceptions about Black women in the legal profession. As a result, I argue that the show’s negative depic- tion of Keating as a Black female attorney can lead to the formation of implicit biases about Black female attorneys, and may contribute to why Black women are having a difficult time excelling in law firms, which are 92.75 percent White. -

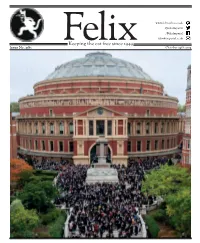

IMPERIAL COLLEGE LONDON FELIX This Week’S Issue

www.felixonline.co.uk @felixImperial /FelixImperial [email protected] Keeping the cat free since 1949 Issue No. 1585 October 24th 2014 2 24.10.2014 THE STUDENT PAPER OF IMPERIAL COLLEGE LONDON FELIX This week’s issue... [email protected] Felix Editor Philippa Skett EDITORIAL TEAM CONTENTS Editor-In-Chief A poorly captioned photo of PHILIPPA SKETT News 3–6 Deputy Editor a man sweeping in Metric PHILIP KENT Comment 7–8 Treasurer THOMAS LIM Features 9–10 speaks a thousand words Technical Hero Science 11 LUKE GRANGER-BROWN ast week we ran two stories the night when the newspaper layout News Editors Technology 12 that we were worried (or did gets too much. If anyone needs any AEMUN REZA Lwe hope?) would cause a storm. post-it notes, give us a shout. CECILE BORKHATARIA Music 15 One was covering the amenities funds Finally, we saw the launch of our KUNAL WAGLE cut, and the other was looking at the amazing, brand new website last first non-alocoholic bar night ran by week. Personally, I was dozing in the Comment Editors Television 16–17 TESSA DAVEY Imperial College Union. Surprisingly, corner after a particularly stressful Film 22–23 the latter story is the one that is submission of the paper the night Technology Editors seemingly kicking up a storm. before, but I heard that it all went JAMIE DUTTON Arts 24–27 We are running a whole page this smoothly and was launched on time. OSAMA AWARA week dedicated to the news story that We are still uploading articles onto Science Editors Food 28–29 only warrented about 200 words in the site a few batches at a time. -

The Black Paper

THE BLACK PAPER THE BLACK PAPER 1 BlkPaper-BB424-2.indd 1 5/15/17 11:34 AM IT’S TIME TO GET SERIOUS ABOUT DIVERSITY. We’re Here. Get Bold. An agency tackling multicultural representation in the media, marketing, advertising, and tech industries through awareness, consulting, and connections. www.boldculture.co 2 THE BLACK PAPER BlkPaper-BB424-2.indd 2 5/15/17 11:34 AM ALL ROADS LEAD TO A FACT QUITE OBVIOUS FOR ADVERTISING AND MARKETING EXECS: BLACK CONSUMERS AND CREATIVES ARE INCREDIBLY INFLUENTIAL. DESPITE THIS, BIG BRANDS MOSTLY STRUGGLE TO REACH AND KEEP THEM. WE OFFER A WAY FORWARD. A PUBLICATION OF THE BLACK PAPER 1 BlkPaper-BB424-2.indd 1 5/15/17 11:34 AM TABLE OF CONTENTS 5 THIS ISN’T KANSAS ANYMORE: MORE LIKE ATLANTA 9 MEASURING INFLUENCE 10 PEPSI POPS ITS OWN BUBBLE 12 DONALD GLOVER AS MARKETING GURU 13 LIKE WILDFIRE 14 BLACK WOMEN DOMINATE 16 IT’S A TRUST THANG 17 HOW HAVE BIG BRANDS GOTTEN IT WRONG? 19 BLACK AMERICANS IN ADVERTISING 25 IMPROVING BRAND OUTREACH 27 NOTES AND REFERENCES 2 THE BLACK PAPER BlkPaper-BB424-2.indd 2 5/15/17 11:34 AM TEAM DARREN MARTIN JR. Chief Executive Officer AHMAD BARBER Chief Creative Officer JARED LOGGINS Contributing Editor Contributors BIANA BAKMAN JUDA BORRAYO STEPHEN FELDMAN BlkPaper-BB424-2.indd 3 5/15/17 11:34 AM IN A WORLD WHERE ANYONE CAN COMMUNICATE WITH ANYONE EVEN ON THE OTHER SIDE OF THE GLOBE HOW DOES YOUR BRAND STAND OUT? 4 THE BLACK PAPER BlkPaper-BB424-2.indd 4 5/15/17 11:34 AM THIS ISN’T KANSAS ANYMORE: MORE LIKE ATLANTA WRITTEN BY: JUDA BORRAYO In the last 20 years, the elevation of targeted majority Black-owned businesses grew 34%.” marketing, big data, and social media has IMPROVED EDUCATION AND Black female-owned businesses represent 59% greatly influenced marketing strategies. -

1144 05/16 Issue One Thousand One Hundred Forty-Four Thursday, May Sixteen, Mmxix

#1144 05/16 issue one thousand one hundred forty-four thursday, may sixteen, mmxix “9-1-1: LONE STAR” Series / FOX TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX TELEVISION 10201 W. Pico Blvd, Bldg. 1, Los Angeles, CA 90064 [email protected] PHONE: 310-969-5511 FAX: 310-969-4886 STATUS: Summer 2019 PRODUCER: Ryan Murphy - Brad Falchuk - Tim Minear CAST: Rob Lowe RYAN MURPHY PRODUCTIONS 10201 W. Pico Blvd., Bldg. 12, The Loft, Los Angeles, CA 90035 310-369-3970 Follows a sophisticated New York cop (Lowe) who, along with his son, re-locates to Austin, and must try to balance saving those who are at their most vulnerable with solving the problems in his own life. “355” Feature Film 05-09-19 ê GENRE FILMS 10201 West Pico Boulevard Building 49, Los Angeles, CA 90035 PHONE: 310-369-2842 STATUS: July 8 LOCATION: Paris - London - Morocco PRODUCER: Kelly Carmichael WRITER: Theresa Rebeck DIRECTOR: Simon Kinberg LP: Richard Hewitt PM: Jennifer Wynne DP: Roger Deakins CAST: Jessica Chastain - Penelope Cruz - Lupita Nyong’o - Fan Bingbing - Sebastian Stan - Edgar Ramirez FRECKLE FILMS 205 West 57th St., New York, NY 10019 646-830-3365 [email protected] FILMNATION ENTERTAINMENT 150 W. 22nd Street, Suite 1025, New York, NY 10011 917-484-8900 [email protected] GOLDEN TITLE 29 Austin Road, 11/F, Tsim Sha Tsui, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China UNIVERSAL PICTURES 100 Universal City Plaza Universal City, CA 91608 818-777-1000 A large-scale espionage film about international agents in a grounded, edgy action thriller. The film involves these top agents from organizations around the world uniting to stop a global organization from acquiring a weapon that could plunge an already unstable world into total chaos. -

O Papel Da Televisão No Streaming: Um Estudo Sobre a Evolução Das Séries Da Produtora Shondaland E Sua Contratação Pela Netflix1

Intercom – Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos Interdisciplinares da Comunicação 41º Congresso Brasileiro de Ciências da Comunicação – Joinville - SC – 2 a 8/09/2018 O Papel da Televisão no Streaming: Um Estudo Sobre a Evolução das Séries da Produtora Shondaland e sua Contratação pela Netflix1 Rhayller Peixoto da Costa Souza2 Júlio Arantes Azevedo3 Universidade Federal de Alagoas, Maceió, AL Resumo O presente artigo busca levantar dados sobre as principais séries da produtora Shondaland e apontar a evolução de suas histórias para um modelo de representatividade, diferente de como eram contadas em seus primeiros anos. Ao longo das temporadas dos seriados produtora, o modo de conduzir os personagens se alinhou a uma demanda de conscientização coletiva, se aproximando do empoderamento feminino e da discussão étnico-racial. A transformação das narrativas em tramas que dialogam com o público de modo didático se projeta para além da televisão, resultando na adesão a elementos televisivos pelo serviço de streaming Netflix, como parte das estratégias para firmar suas relações com o consumidor da tevê que quer ver esses debates incorporados nos produtos que assiste. Palavras-chave: Grey’s Anatomy ; Netflix ; televisão ; personagem Introdução No ano de 2015 a Revista Exame destacou a consolidação da Netflix como distribuidor de audiovisual via streaming como um dos grandes acontecimentos da era digital. O modo operacional da empresa, que disponibiliza seu conteúdo on demand4 é atrativo ao consumidor, criando uma relação em que a vontade do usuário prevalece sobre o que é consumido, uma rotina bem diferente da apresentada pela televisão desde sua popularização, na segunda metade do século passado. A chegada do serviço de streaming criou, além da excitação pela novidade, uma ideia de quebra de vínculo do 1 Trabalho apresentado no IJ DT4 - Comunicação Audiovisual - do 41º Congresso Brasileiro de Ciências da Comunicação. -

Network Telivision

NETWORK TELIVISION NETWORK SHOWS: ABC AMERICAN HOUSEWIFE Comedy ABC Studios Kapital Entertainment Wednesdays, 9:30 - 10:00 p.m., returns Sept. 27 Cast: Katy Mixon as Katie Otto, Meg Donnelly as Taylor Otto, Diedrich Bader as Jeff Otto, Ali Wong as Doris, Julia Butters as Anna-Kat Otto, Daniel DiMaggio as Harrison Otto, Carly Hughes as Angela Executive producers: Sarah Dunn, Aaron Kaplan, Rick Weiner, Kenny Schwartz, Ruben Fleischer Casting: Brett Greenstein, Collin Daniel, Greenstein/Daniel Casting, 1030 Cole Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90038 Shoots in Los Angeles. BLACK-ISH Comedy ABC Studios Tuesdays, 9:00 - 9:30 p.m., returns Oct. 3 Cast: Anthony Anderson as Andre “Dre” Johnson, Tracee Ellis Ross as Rainbow Johnson, Yara Shahidi as Zoey Johnson, Marcus Scribner as Andre Johnson, Jr., Miles Brown as Jack Johnson, Marsai Martin as Diane Johnson, Laurence Fishburne as Pops, and Peter Mackenzie as Mr. Stevens Executive producers: Kenya Barris, Stacy Traub, Anthony Anderson, Laurence Fishburne, Helen Sugland, E. Brian Dobbins, Corey Nickerson Casting: Alexis Frank Koczaraand Christine Smith Shevchenko, Koczara/Shevchenko Casting, Disney Lot, 500 S. Buena Vista St., Shorts Bldg. 147, Burbank, CA 91521 Shoots in Los Angeles DESIGNATED SURVIVOR Drama ABC Studios The Mark Gordon Company Wednesdays, 10:00 - 11:00 p.m., returns Sept. 27 Cast: Kiefer Sutherland as Tom Kirkman, Natascha McElhone as Alex Kirkman, Adan Canto as Aaron Shore, Italia Ricci as Emily Rhodes, LaMonica Garrett as Mike Ritter, Kal Pennas Seth Wright, Maggie Q as Hannah Wells, Zoe McLellan as Kendra Daynes, Ben Lawson as Damian Rennett, and Paulo Costanzo as Lyor Boone Executive producers: David Guggenheim, Simon Kinberg, Mark Gordon, Keith Eisner, Jeff Melvoin, Nick Pepper, Suzan Bymel, Aditya Sood, Kiefer Sutherland Casting: Liz Dean, Ulrich/Dawson/Kritzer Casting, 4705 Laurel Canyon Blvd., Ste.