Fish Communities and Fisheries in Wales's National Nature Reserves: a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dolgarrog, Conwy

900 Dolgarrog Hydro-Electric Works: Dolgarrog, Conwy Archaeological Assessment GAT Project No. 2158 Report No. 900 November, 2010 Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Gwynedd Gwynedd Archaeological Trust Craig Beuno, Ffordd y Garth, Bangor, Gwynedd, ll57 2RT Archaeological Assessment: Dolgarrog Hydro-Electric Works Report No. 900 Prepared for Capita Symonds November 2010 By Robert Evans Ymddiriedolaeth Archaeolegol Gwynedd Gwynedd Archaeological Trust Craig Beuno, Ffordd y Garth, Bangor, Gwynedd, LL57 2RT G2158 HYDRO-ELECTRIC PIPELINE, DOLGARROG ARCHAEOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT Project No. G2158 Gwynedd Archaeological Trust Report No. 900 CONTENTS Page Summary 3 1. Introduction 3 2. Project brief and specification 3 3. Methods and Techniques 4 4. Archaeological Results 7 5. Summary of Archaeological Potential 19 6. Summary of Recommendations 20 7. Conclusions 21 8. Archive 22 9. References 22 APPENDIX 1 Sites on the Gwynedd HER within the study area APPENDIX 2 Project Design 1 Figures Fig. 1 Site Location. Base map taken from Ordnance Survey 1:10 000 sheet SH76 SE. Crown Copyright Fig. 2 Sites identified on the Gwynedd HER (Green Dots), RCAHMW survey (Blue Dots) and Walk-Over Survey (Red Dots). Map taken from Ordnance Survey 1:10 000 sheets SH 76 SE and SW. Crown Copyright Fig. 3 The Abbey Demesne, from Plans and Schedule of Lord Newborough’s Estates c.1815 (GAS XD2/8356- 7). Study area shown in red Fig. 4 Extract from the Dolgarrog Tithe map of 1847. Field 12 is referred to as Coed Sadwrn (Conwy Archives) Fig. 5 The study area outlined on the Ordnance Survey 25 inch 1st edition map of 1891, Caernarvonshire sheets XIII.7 and XIII.8, prior to the construction of the Hydro-Electric works and dam. -

Wales: River Wye to the Great Orme, Including Anglesey

A MACRO REVIEW OF THE COASTLINE OF ENGLAND AND WALES Volume 7. Wales. River Wye to the Great Orme, including Anglesey J Welsby and J M Motyka Report SR 206 April 1989 Registered Office: Hydraulics Research Limited, Wallingford, Oxfordshire OX1 0 8BA. Telephone: 0491 35381. Telex: 848552 ABSTRACT This report reviews the coastline of south, west and northwest Wales. In it is a description of natural and man made processes which affect the behaviour of this part of the United Kingdom. It includes a summary of the coastal defences, areas of significant change and a number of aspects of beach development. There is also a brief chapter on winds, waves and tidal action, with extensive references being given in the Bibliography. This is the seventh report of a series being carried out for the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. For further information please contact Mr J M Motyka of the Coastal Processes Section, Maritime Engineering Department, Hydraulics Research Limited. Welsby J and Motyka J M. A Macro review of the coastline of England and Wales. Volume 7. River Wye to the Great Orme, including Anglesey. Hydraulics Research Ltd, Report SR 206, April 1989. CONTENTS Page 1 INTRODUCTION 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 COASTAL GEOLOGY AND TOPOGRAPHY 3.1 Geological background 3.2 Coastal processes 4 WINDS, WAVES AND TIDAL CURRENTS 4.1 Wind and wave climate 4.2 Tides and tidal currents 5 REVIEW OF THE COASTAL DEFENCES 5.1 The South coast 5.1.1 The Wye to Lavernock Point 5.1.2 Lavernock Point to Porthcawl 5.1.3 Swansea Bay 5.1.4 Mumbles Head to Worms Head 5.1.5 Carmarthen Bay 5.1.6 St Govan's Head to Milford Haven 5.2 The West coast 5.2.1 Milford Haven to Skomer Island 5.2.2 St Bride's Bay 5.2.3 St David's Head to Aberdyfi 5.2.4 Aberdyfi to Aberdaron 5.2.5 Aberdaron to Menai Bridge 5.3 The Isle of Anglesey and Conwy Bay 5.3.1 The Menai Bridge to Carmel Head 5.3.2 Carmel Head to Puffin Island 5.3.3 Conwy Bay 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7 REFERENCES BIBLIOGRAPHY FIGURES 1. -

A Warm Welsh Welcome to Adventure Parc

A breathtaking venue with your wellbeing at heart. Come to North Wales to experience exceptional hospitality, adventures and incentives, delivered by our award-winning team. ADVENTUREPARCSNOWDONIA.COM Conway Rd, Dolgarrog, Conwy, LL32 8QE. 01492 353 123 #AdventureAwaits [email protected] You’ll find us in the Conwy Valley, a short distance from Conwy and Betws y Coed on the edge of the A WARM WELSH Snowdonia National Park. It’s easy to get WELCOME TO ADVENTURE here! TRAVEL TIMES TRAVEL 60 MINUTES FROM CHESTER PARC SNOWDONIA 90 MINUTES FROM LIVERPOOL 100 MINUTES FROM MANCHESTER 145 MINUTES FROM BIRMINGHAM We offer one-of-a-kind team building and incentive experiences, as well as showstopper events, 180 MINUTES* FROM LONDON *BY TRAIN conference & meeting facilities at our beautiful new hotel and spa. From surfing on man-made waves to indoor caving, ninja assault courses to mountain biking and zip lines, our adventures are designed to invigorate, exhilarate and pump up your team. Check in for luxurious hospitality at our Hilton Garden Inn, or treat the team to a day of relaxation at the Wave Garden Spa followed WITH THE FORESTS AND by an evening to remember at our stunning restaurant & bar. Our friendly events team is here to help you plan every step of the way. MOUNTAINS OF NORTH WALES [email protected] | 01492 353 123 ON OUR DOORSTEP, THERE’S PLENTY OF ROOM TO ENJOY THE FREEDOM OF FRESH WE’RE GOOD TO GO! AIR AND BIG OPEN SPACES. As members of the We’re Good to Go, Hilton Clean Stay, and Hilton Event Ready schemes, you can be assured that we are following the most scrupulous COVID-19 COME RAIN OR SHINE guidelines. -

Mike Peacock Phd 2013.Pdf

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The effect of peatland rewetting on gaseous and fluvial carbon losses from a Welsh blanket bog Peacock, Michael Award date: 2013 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 The Effect of Peatland Rewetting on Gaseous and Fluvial Carbon Losses from a Welsh Blanket Bog Michael Anthony Peacock PhD Thesis School of Biological Sciences Bangor University Declaration and Consent Details of the Work I hereby agree to deposit the following item in the digital repository maintained by Bangor University and/or in any other repository authorized for use by Bangor University. Author Name: ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Title: ………………………………………………………………………………………..………………………. Supervisor/Department: .................................................................................................................. Funding body (if any): ........................................................................................................................ Qualification/Degree obtained: ………………………………………………………………………. This item is a product of my own research endeavours and is covered by the agreement below in which the item is referred to as “the Work”. -

PLACE-NAMES of FLINTSHIRE

1 PLACE-NAMES of FLINTSHIRE HYWEL WYN OWEN KEN LLOYD GRUFFYDD 2 LIST A. COMPRISES OF THE NAMED LOCATIONS SHOWN ON THE ORDNANCE SURVEY LANDRANGER MAPS, SCALE 1 : 50,000 ( 2009 SELECTED REVISION ). SHEETS 116, 117, 126. 3 PLACE-NAMES NGR EARLY FORM(S) & DATE SOURCE / COMMENT Abbey Farm SJ 0277 The Abby 1754 Rhuddlan PR Plas newydd or Abbey farm 1820 FRO D/M/830. Plas Newydd or Abbey Farm 1849 FRO D/M/804. Aberduna SJ 2062 Dwi’n rhyw amau nad yw yn Sir y Fflint ? Aberdunne 1652 Llanferres PR Aberdynna 1674 “ “ Aberdynne 1711 “ “ Aberdinna 1726 “ “ Aber Dinna 1739 “ “ Aberdyne 1780 “ “ Aberdine 1793 “ “ Abermorddu SJ 3056 Abermoelduy 1378 CPR,1377-81, 233. Aber mole (sic) 1587 FRO, D/GW/1113. Aber y Moel du 1628 BU Bodrhyddan 719. Abermorddu 1771 Hope PR Abermorddu 1777 Hope PR Abermordy 1786 Hope PR Abermorddu 1788 Hope PR Abermordy 1795 Hope PR Abermorddy 1795 John Evans’ Map. Abermordey 1799 Hope PR Abermorddu 1806 Hope PR Abermorddy 1810 Hope PR Abermorddu 1837 Tithe Schedule Abermorddu 1837 Cocking Index, 13. Abermorddu 1839 FHSP 21( 1964 ), 84. Abermorddu 1875 O.S.Map. [ Cymau ] Referred to in Clwyd Historian, 31 (1993 ), 15. Also in Hope Yr : Aber-ddu 1652 NLW Wigfair 1214. Yr Avon dhŷ 1699 Lhuyd, Paroch, I, 97. Yr Aberddu 1725 FHSP, 9( 1922 ), 97. Methinks where the Black Brook runs into the Alun near Hartsheath ~ or another one? Adra-felin SJ 4042 Adravelin 1666 Worthenbury PR Radevellin 1673 Worthenbury PR Adrevelin 1674 Worthenbury PR Adafelin 1680 Worthenbury PR Adwefelin, Adrefelin 1683 Worthenbury PR Adavelin 1693 Worthenbury PR Adavelin 1700 Worthenbury PR Adavelen 1702 Worthenbury PR 4 Adruvellin 1703 Bangor Iscoed PR Adavelin 1712 Worthenbury PR Adwy’r Felin 1715 Worthenbury PR Adrefelin 1725 Worthenbury PR Adrefelin 1730 Worthenbury PR Adravelling 1779 Worthenbury PR Addravellyn 1780 Worthenbury PR Addrevelling 1792 Worthenbury PR Andravalyn 1840 O.S.Map.(Cassini) Aelwyd-uchaf SJ 0974 Aelwyd Ucha 1632 Tremeirchion PR Aylwyd Ucha 1633 Cwta Cyfarwydd, 147. -

Adventures in North Wales This Is Where It All Begins

STAG & HEN ADVENTURES IN NORTH WALES THIS IS WHERE IT ALL BEGINS... We’ll help you put together a uniquely brilliant send off for the bride or groom to be. ADVENTUREPARCSNOWDONIA.COM Conway Rd, Dolgarrog, Conwy, LL32 8QE. 01492 353 123 #AdventureAwaits [email protected] You’ll find us in the FOR LEGENDARY Conwy Valley, a short distance from Conwy and Betws y Coed STAG AND HEN on the edge of the Snowdonia National Park. It’s easy to get ADVENTURES here! TRAVEL TIMES TRAVEL 60 MINUTES FROM CHESTER Looking for an alternative to the traditional do? We can help you to put together a 90 MINUTES FROM LIVERPOOL legendary trip. 100 MINUTES FROM MANCHESTER 145 MINUTES FROM BIRMINGHAM From surfing on man-made waves, to ninja assault courses and zip lines, gorge walking to mountain bikes, we have everything you *BY TRAIN need to make it an experience to remember. 180 MINUTES* FROM LONDON Check in for some deep relaxation at our brand new Wave Garden Spa, followed by luxurious hospitality at our Hilton Garden Inn, or stay over in our comfortable wooden glamping pods. However you want to do it, our dedicated events team will make sure it all goes off without a hitch. Just drop us a line to start planning your trip! WITH THE FORESTS AND [email protected] | 01492 353 123 MOUNTAINS OF NORTH WALES ON OUR DOORSTEP, THERE’S PLENTY OF ROOM TO WE’RE GOOD TO GO! ENJOY THE FREEDOM OF FRESH AIR AND BIG OPEN SPACES. As members of the We’re Good to Go, Hilton Clean Stay, and Hilton Event Ready schemes, you can be assured that we are following the most scrupulous COVID-19 COME RAIN OR SHINE guidelines. -

Ommatoiulus Moreleti (Lucas) and Cylindroiulus

Bulletin of the British Myriapod & Isopod Group Volume 30 (2018) OMMATOIULUS MORELETI (LUCAS) AND CYLINDROIULUS PYRENAICUS (BRÖLEMANN) NEW TO THE UK (DIPLOPODA, JULIDA: JULIDAE) AND A NEW HOST FOR RICKIA LABOULBENIOIDES (LABOULBENIALES) Steve J. Gregory1, Christian Owen2, Greg Jones and Emma Williams 1 4 Mount Pleasant Cottages, Church Street, East Hendred, Oxfordshire, OX12 8LA, UK. E-mail: [email protected] 2 75 Lewis Street, Aberbargoed. CF8 19DZ, UK. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The schizophylline millipede Ommatoiulus moreleti (Lucas) and the cylindroiuline millipede Cylindroiulus pyrenaicus (Brölemann) (Julida: Julidae) are recorded new for the UK from a site near Bridgend, Glamorganshire, in April 2017. An unidentified millipede first collected in April 2004 from Kenfig Burrows, Glamorganshire, is also confirmed as being C. pyrenaicus. Both species are described and illustrated, enabling identification. C. pyrenaicus is reported as a new host for the Laboulbeniales fungus Rickia laboulbenioides. Summary information is provided on habitat preferences of both species in South Wales and on their foreign distribution and habitats. It is considered likely that both species have been unintentionally introduced into the UK as a consequence of industrial activity in the Valleys of south Wales. INTRODUCTION The genera Ommatoiulus Latzel, 1884 and Cylindroiulus Verhoeff, 1894 (Julida: Julidae) both display high species diversity (Kime & Enghoff, 2017). Of the 47 described species of Ommatoiulus the majority are found in North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula (ibid). Currently, just one species, Ommatoiulus sabulosus (Linnaeus, 1758), is known from Britain and Ireland, a species that occurs widely across northern Europe (Kime, 1999) and in Britain reaches the northern Scottish coastline (Lee, 2006). -

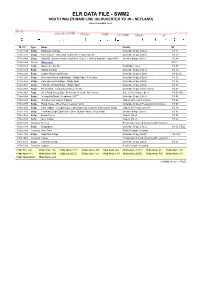

Elr Data File - Swm2 South Wales Main Line (Gloucester Yd Jn - Neyland)

ELR DATA FILE - SWM2 SOUTH WALES MAIN LINE (GLOUCESTER YD JN - NEYLAND) www.railwaydata.co.uk M. Ch. Type Name Details ID 113m 11ch Bridge Millstream Subway Underline Bridge | Steel 113 11 113m 13ch Bridge River Twyver - Also Under Chl At 92 78. Over Stream Underline Bridge | Steel 113 13 113m 44ch Bridge Windmill - Eastern Radial Road Over. Glos C.c. Own & Maintain - Agmt.rt510 Overline Bridge | Steel 113 44 114m 04ch Station Gloucester GCR 114m 07ch Bridge Gloucester Stn Fb - Footbridge | Steel 114 07 114m 12ch Bridge Station Subway Underline Bridge | Steel 114 12 114m 22ch Bridge London Road Underbridge Underline Bridge | Steel 114 21.25 114m 32ch Bridge Worcester Street Underbridge - Single Span. A38 Under Underline Bridge | Steel 114 32 114m 35ch Bridge Hare Lane Underbridge - Single Span Underline Bridge | Brick 114 35 114m 36ch Bridge Park Street Underbridge - Single Span Underline Bridge | Brick 114 36 114m 47ch Bridge Deans Walk - Closed To Vehicular Traffic Underline Bridge | Brick (Arch) 114 47 114m 54ch Bridge Over Road On Up Side. (fb Not On Nr Land - No Exams) Side of Line Bridge | Steel 114 54 B/S 114m 54ch Bridge "st.oswalds Road - Headroom 16'0""" Underline Bridge | Steel 114 54 115m 02ch Bridge St Catherines Viaduct 7 Spans Viaduct | Pre-cast Concrete 115 02 115m 07ch Bridge Pump House - River Severn (eastern Arm) Underline Bridge | Pre-tensioned Concrete 115 07 115m 16ch Bridge Ham Viaduct - 12 Spans (pre Cast Segmental Concrete Arches Over Land) Viaduct | Pre-cast Concrete 115 16 115m 31ch Bridge Townham Single Span -

Bridgend Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation Review December 2011

Bridgend Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation Review December 2011 Quality Management Job No GC/001170 Doc No. Title Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation Review Location Bridgend Document Ref File reference Date December 2011 Sarah Simons Prepared by Principal Ecologist 19-12-11 BSc (Hons), MSc, MIEEM Lucy Fay Checked by Senior Ecologist 19-12-11 BSc (Hons), AIEEM Ian Walsh Authorised by Technical Director 19-12-11 BSc, CEng, MICE, MCIHT Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Review objectives 1 2. METHODOLOGY 2 2.1 Introduction 2 2.2 Desktop Study 2 2.3 Field Survey 3 2.4 Constraints 4 3. OVERVIEW OF RESULTS 5 3.1 Sites that no longer qualify as SINCS 5 3.2 Sites that require re-survey to confirm status 6 3.3 Sites that should be upgraded from cSINC to SINC 6 4. RECOMMENDATIONS 7 4.1 Identifying new SINCs 7 4.2 SINC administration 7 4.3 SINC habitat management 8 5. REFERENCES 10 APPENDICES 11 i 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 BACKGROUND Bridgend County Borough Council commissioned Capita Symonds to carry out a review of its Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs). The review included both desk-based studies and field work. This report will provide a record of the methodologies used and a summary of the findings of the review along with recommendations for further work. 1.2 REVIEW OBJECTIVES • To confirm or otherwise that the Council’s suite of SINCs meet a robust set of criteria (Wildlife Sites Guidance Wales – A Guide to Develop Local Wildlife Systems in Wales (Wales Biodiversity Partnership, 2008)) • To provide SINC data sufficient to inform the emerging Local Development Plan (LDP) and the planning process. -

NAO CAMS2 Nancy.QXD

www.environment-agency.gov.uk/cams The Neath, Afan and Ogmore Catchment Abstraction Management Strategy October 2005 www.environment-agency.gov.uk/cams The Environment Agency is the leading public body protecting and improving the environment in England and Wales. It’s our job to make sure that air, land and water are looked after by everyone in today’s society, so that tomorrow’s generations inherit a cleaner, healthier world. Our work includes tackling flooding and pollution incidents, reducing industry’s impacts on the environment, cleaning up rivers, coastal waters and contaminated land, and improving wildlife habitats. Published by: Environment Agency Wales Cambria House 29 Newport Road Cardiff, CF24 0TP Tel: 08708 506 506 IC code: GEWA 1005BJNM-B-P © Environment Agency Wales All rights reserved. This document may be reproduced with prior permission of the Environment Agency. This report is printed using water based inks on Revive, a recycled paper combining at least 75% de-inked post consumer waste and 25% mill broke. Front cover photograph by David Dennis, Environmental Images. Foreword Water is so often taken for granted, especially in Wales. After all, it seems to be raining rather often, so surely there has to be a plentiful supply for all our needs! And our needs are many and varied. All our houses need water; hospitals need water; industries need water; breweries need water; some recreational activities need water, this list is endless, and at the same time we need to ensure that we keep enough water in the rivers to protect the environment. It follows that this precious resource has to be carefully managed if all interests, often conflicting, can be properly served. -

ANNUAL REPORT for the Royal Air Force Mountain Rescue Service AS the NEW TL at RAF Kinloss As a Part-Time Troop

ANNUAL REPO RT 5ADRODDIAD 3 BLYNYDDOL Ogwen Valley Mountain Rescue Organisation Sefydliad Achub Mynydd Dyffryn Ogwen The Ogwen Valley Mountain Rescue Organisation 53 rd ANNUAL REPO RT FOR THE YEAR 2017 Bryn Poeth, Capel Curig, Betws y Coed, Conwy L L24 0EU T: +44 (0)1690 720333 E: [email protected] W: ogwen-rescue.org.uk Published by the Ogwen Valley Mountain Rescue Organisation © OVMRO 20 18 Edited by Russ Hore • Designed by Judy Whiteside Front cover: Night rescue with helicopter © Karl Lester Back cover: Dyffryn Ogwen © Lawrence Cox Argraffwyd gan/Printed by Browns CTP Please note that the articles contained in this report express the views of the individuals and are not necessarily the views of the team. Christmas photography competition winner 2017: Castell y Gwynt © Neil Murphy. 5 Chairman’s Report 9 Adroddiad y Cadeirydd 14 Team Leader 18 Incidents: January 20 Incidents: February 21 Incidents: March 23 Incidents: April 25 Incidents: May 28 Incidents: June 28 Incidents: July 34 Incidents: August 37 Incidents: September 38 Incidents: October 41 Incidents: November 42 Incidents: December 44 Incident Summary 46 Casual ty Care 49 Equipment Officer 53 Press Officer 57 Training Officer s 58 IT Group t 61 Treble Three 67 Treasurer n 69 Collection Boxes e 70 Trustees Report t 73 Accounts 81 Shop n o c 3 14 January 2018: Call-out No 6 : Tryfan: We were called to search for a walker reported overdue. In worsening weather, twelve team members searched Cwm Tryfan, Heather Terrace and along the foot of the West Face, through into the early hours with nothing found. -

Snowdonia Green Key Strategy Appraisal Document and User Survey Snowdonia Active – Eryri Bywiol Feb/March 2002 V3.00

Snowdonia Green Key Strategy Appraisal Document and User Survey Snowdonia Active – Eryri Bywiol Feb/March 2002 V3.00 1 Snowdonia-Active Snowdonia-Active is a recently formed group of independent freethinking business people from within the Gwynedd, Môn and the rural Conwy area. We have come together as a result of sharing a common desire to better promote and safeguard Adventure Tourism and associated Outdoor Industries within our geographical area. We see a need for a unifying group bringing together all the elements that give the Adventure Tourism and associated Outdoor Industries their special Snowdonia magic. The group represents a broad spectrum of those elements, from Freelance Instructors, Heads of Outdoor Centres and Management Development Companies to Equipment Manufacturers, Retailers and Service Industries. We believe that the best way to protect the interests of our industry, it’s customers and the environment is by coming together to promote and develop the valuable contribution that we make to the local economy. 2 Introduction This report was co-ordinated by Snowdonia-Active to provide a structured insight into the possible impact of the proposed Snowdonia Green Key Strategy (GKS) upon local outdoor orientated businesses and outdoor adventure/recreational users of Northern Snowdonia. It was deeply felt and vociferously expressed that the Green Key Strategy failed to consult with these user groups. Since the GKS argues strongly for reforms to aid the economic development of the area, the lack of consultation with the outdoor business sector has resulted in many of the positive aspects of the strategy being overshadowed by controversy surrounding the plans for the enforced Park & Ride scheme.