Making Connections: a Literacy And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSITY of CALGARY the Kootenay School of Writing: History

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Kootenay School of Writing: History, Community, Poetics Jason Wiens A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 200 1 O Jason Wiens 200 1 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1+1 of canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellingion Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your lils Votre r6Orence Our file Notre rdfdtencs The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/^, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être implimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract Through a method which combines close readings of literary texts with archiva1 research, 1provide in this dissertation a critical history of the Kootenay School of Writing (KSW): an independent, writer-run centre established in Vancouver and Nelson, British Columbia in 1984. -

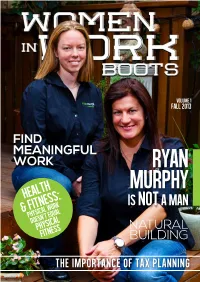

Read the Fall 2013 Edition with a Detailed Report On

VOLUME 1 FALL 2013 FIND MEANINGFUL WORK RYAN MURPHY HEALTH & FITNESS: IS NOT A MAN PHYSICAL WORK doesn’t equal PHYSICAL NATURAL FITNESS BUILDING THE IMPORTANCE OF TAX PLANNING LETTER FROM THE EDITOR “Be true to who you are. We have to fit into this out in the next other world and be true to who we are. That’s couple of weeks CONTENTS the challenge.” in our website and Facebook page, so THROUGH SHARING THE STORIES OF OTHER WOMEN keep checking in!). WORKING IN THE CONSTRUCTION INDUSTRY OR WITH A hese words were spoken to me only months After spending CRAFT, WE HOPE THAT YOU WILL FIND WHAT YOU NEED TO ago by an amazing Journeyman Plumber/ eight years in GET TO WORK OR TELL ANOTHER WOMAN ABOUT WHAT T Pipefitter, and advocate for women in the more than 20 You’ve learned. trades, Tamara Pongracz. Although I wish I countries, I began had been able to hear these words when I started my my career as a tile journey into the construction industry, I’m elated that setter because I other women can now read them and embark on a was so enamored personal challenge to join this amazing industry filled and interested in 3 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR with upcoming opportunities for students, employees, the infrastructure JILL DRADER and especially, business owners. in other countries. These SMART TRUCKING WITH Working in the construction industry isn’t easy. A pink 23 infrastructures CATHERINE MACMILLAN portable toilet and pink hard hats haven’t eliminated were built the fact that the industry itself is cyclical, and like the 10 EDUCATION INSTITUTES hundreds and thousands of years ago and were still 4 economy, it isn’t as predictable as we would like to IN WESTERN CANADA standing. -

News from the Feminist Caucus, by Anne Burke

News from the Feminist Caucus, by Anne Burke We welcome new members who share the goals and objectives of The Feminist Caucus. If you will be attending the agm in Toronto, June 7-9, please join us for the panel on Friday at 2 p.m.-3 p.m. and the brief Business Meeting (to plan 2014) & Reading at 3 p.m.-4 pm; and, on Saturday, the Open Reading at 4:15 p.m. -5:15 p.m., when we will be launching Poetry & The Disordered Mind , edited by Lynda Monahan, with readers Penn Kemp and Janet Vickers. This month, we also feature a brand-new review by Susan McCaslin of Doyali Farah Islam’s Yūsuf and the Lotus Flower (Ottawa: BuschekBooks, 2011); in addition to Previews of Untying the Apron Strings, Daughters Remember Mothers of the 1950s (Toronto: Guernica Books ) AND Force Field - 77 Women Poets of British Columbia , edited by Susan Musgrave (Salt Spring Island B.C.: Mother Tongue Press). Schedule: Friday, June 7, 2013 The Feminist Caucus Panel 2013 is at 2 pm Note: Immediately following the Panel, at 3 pm, there will be a brief business meeting to plan next year's program. Come and join us! Then we have an open reading , all welcome, until 4 pm. Schedule: Saturday, June 8, 2013 , there is the Fem Caucus Open Reading (all welcome) at 4:15 pm. We will be launching Poetry & the Disordered Mind . Janet Vickers and Penn Kemp contributors, will be two of the readers. Winners of the Pat Lowther Memorial Award will be announced during a special ceremony at the annual LCP Poetry Fest and Conference to be held at the Courtyard by Marriott Hotel in downtown Toronto on June 8, 2013. -

A Self-Made Queen Margaret Atwood and the Hard Work of Literary Celebrity

Talking excrement PAGE 6 $6.50 Vol. 21, No. 6 July/August 2013 Suanne Kelman A Self-Made Queen Margaret Atwood and the hard work of literary celebrity ALSO IN THIS ISSUE Geoffrey Cameron The Baha’i exodus to Canada Sarah Elton vs. Pierre Desrochers Food fight for the planet Rudy Buttignol Can the CBC be saved? PLUS: NON-FICTION Hugh Segal on one of Canada’s most genial immigrants + Frances Henry on black power in Montreal + Rinaldo Walcott on book burnings and other anti-racist gestures + Christopher Pennington on Canadians in the U.S. Civil War + Sophie McCall on Grey Owl’s forgotten wife + Michael Taube on Canada’s forgotten royal + Laura Robinson on residential Publications Mail Agreement #40032362 schools + Barbara Yaffe on Ontario as seen from Quebec Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to LRC, Circulation Dept. FICTION Marian Botsford Fraser on Flee, Fly, Flown + Deborah Kirshner on The Blue Guitar PO Box 8, Station K Toronto, ON M4P 2G1 POETRY Elana Wolff + Kirsteen MacLeod + Maureen Hynes + Ruth Roach Pierson + Mary Rykov New from UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Across the Aisle Margaret Atwood and the Pathogens for War Opposition in Canadian Politics Labour of Literary Celebrity Biological Weapons, Canadian Life Scientists, and North American Biodefence by David E. Smith by Lorraine York by Donald Avery How do opposition parties influence How does internationally renowned author Canadian politics? Across the Aisle Margaret Atwood maintain her celebrity Donald Avery investigates the challenges of illuminates both the historical evolution status? This book explores the ways bioterrorism, Canada’s secret involvement and recent developments of opposition in which careers of famous writers are with biological warfare, and presents new politics in Canada. -

Libraries and Cultural Resources

LIBRARIES AND CULTURAL RESOURCES Archives and Special Collections Suite 520, Taylor Family Digital Library 2500 University Drive NW Calgary, AB, Canada T2N 1N4 www.asc.ucalgary.ca Zoë Landale fonds. ACU SPC F0142 https://searcharchives.ucalgary.ca/zoe-landale-fonds An additional finding aid in another format may exist for this fonds or collection. Inquire in Archives and Special Collections. ZOË LANDALE fonds ACCESSION NO.: 741/03.6 The Zoe Landale Fonds Accession No. 741/03.6 CORRESPONDENCE ....................................................................................................................................... 3 JOURNALS ................................................................................................................................................... 85 MANUSCRIPTS ............................................................................................................................................. 85 Poetry ...................................................................................................................................................... 85 Collected Poems...................................................................................................................................... 86 Fiction ...................................................................................................................................................... 94 Novels ................................................................................................................................................. -

October 2014 Volume 11, Number 9

St@nza – October 2014 Volume 11, Number 9 To include your news, events or other listings please contact Ingel Madrus at: Email: [email protected], Phone: 416‐504‐1657, Fax: 416‐504‐0096 News from the League Page 1 Opportunities Page 2 New Members Page 9 Poetry and Literary New Page 1 Events & Readings Page 5 Members News Page 10 NEWS FROM THE LEAGUE Deadline November 1! Submit Your Titles for the League Book Awards The deadline for submission to these awards is November 1st, 2014. For books that are published after this date, but still within the calendar year, please e‐mail me by November 1st, 2014 to arrange to have the deadline extended to Dec 15th. Please note: Titles will not be accepted past the deadline unless these arrangements have been made prior to November 1, 2014. If you are a League member, please contact your publisher to see if your title has been submitted before sending it in yourself to avoid duplication. For more information on these awards, and to download a submission form, please go to: http://poets.ca/contests‐awards/ The Al Purdy A‐frame Association Naming Opportunity The Al Purdy A‐frame Association has a naming opportunity and is hoping League members will help out. The A‐frame needs new decks. If League members collectively donate $1500 then one deck at the A‐ frame will have a plaque that will read “The League of Canadian Poets' Deck.” If 150 members donate $10 each, we make the target. Susan McMaster has already kicked off the campaign by donating $50 (donations of $50 or more receive a tax receipt). -

Take on the Challenge. INSTITUTION World Education, Inc., Boston, MA

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 481 355 CE 085 567 AUTHOR Morrish, Elizabeth; Horsman, Jenny; Hofer, Judy TITLE Take on the Challenge. INSTITUTION World Education, Inc., Boston, MA. PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 200p.; Supported by the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education, Women's Educational Equity Act Program. AVAILABLE FROM World Education, Inc., 44 Farnsworth Street, Boston, MA 02210 ($15) .Tel: 617-482-9485; Fax: 617-482-0617; e-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://www.worlded.org/. For full text: http://www.worlded.org/docs/TakeOnTheChallenge.pdf. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Access to Education; Adult Basic Education; Adult Educators; Adult Literacy; Art Education; Art Expression; Creativity; Curriculum Development; *Educational Environment; *Educational Practices; *Empowerment; Equal Opportunities (Jobs); Guidelines; Learning Activities; Resource Materials; Self Concept; Teacher Role; Teacher Student Relationship; *Violence; *Womens Education IDENTIFIERS Study Circles ABSTRACT This document is a sourcebook of ideas and materials for adult basic education teachers and others who want to design programming allowing women who have experienced the impact of violence to learn successfully. The sourcebook consists of three chapters that all contain an introduction, tools for programs, and examples from programs. The topics examined in the three chapters are as follows:(1) taking on the challenge of helping women who have felt the impacts of violence (reasons for addressing -

1 CURRICULUM VITAE of NANCY JANOVICEK Associate Professor Social Sciences 612 Department of History 2500 University Driv

CURRICULUM VITAE OF NANCY JANOVICEK Associate Professor Social Sciences 612 Department of History 2500 University Drive NW University of Calgary Calgary, AB T2N 1N4 Email: [email protected] Phone Number: 403-220-6403 Fax: 403 403-289-8566 EDUCATION SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY PhD, History (2002) Dissertation: “No Place to Go: Women’s Activism, Family Violence and the Mixed Social Economy, Northwestern Ontario and the Kootenays, BC, 1965-1989” Fields: Canadian Social and Cultural History, Gender and Modern European History, Human and Social Geography CARLETON UNIVERSITY MA, CanaDian StuDies (Women’s StuDies Stream) (1997) Thesis: “Finding a Place: The Politics of Feminist Organizing Against Spousal Assault in Ottawa and Lanark County, 1972-1982” UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA BA, Honours History (1991) CURRENT RESEARCH INTERESTS: • My current research project examines the impact of the back-to-the-land movement on the West Kootenays, British Columbia. • Carmen Neilson and I are editing A Companion to Women’s and Gender History in Canada. • I have initiated The Annie Gale Project, a community-based project aims to commemorate the political work of Calgary’s first female Alderman through various public history projects, including a bronze. GRANTS, FELLOWSHIPS, SCHOLARSHIPS, AND AWARDS 2014 University Research Grants Committee Seed Grant, $14, 547.00 2012 SSHRC Awards to Scholarly Publications Program, $8,000.00 (with Dr. Catherine Carstairs, University of Guelph) SSHRC Aid to Research Workshops and Conferences Grant, $25,685.00 2011-2012 Calgary Institute -

Fall 2020 Catalogue

CAITLIN PRESS WHERE URBAN MEETS RURAL & HOME OF DAGGER EDITIONS FALL 2020 Mary Jayne Blackmore Vera Maloff Claire Finlayson Cathy Sosnowsky Kate Braid Mary MacDonald Shannon McConnell Jane Byers Kelly Rose Pflug-Back PRAISE FOR OUR BOOKS “A compelling, thoroughly researched tale of love and death on the BC prairie. Reimer’s book [The Trials of Albert Stroebel] is a gift to history nerds and true-crime lovers alike” —Jesse Donaldson “Accepting yourself at every size? That means rejecting all the whispered edicts of Eurowestern society and the out-loud abuse of strangers. That’s a BIG project. And one worth documenting. As a BIG girl myself, I NEEDED all the stories in [BIG: Stories about Life in Plus-Sized Bodies], from the sad-stark-raging to the joyful-triumphant-funny.” —Ariel Gordon “Furs and gold may dominate BC’s modern creation narrative, but it was the packtrain that made it possible. ... Cataline: The Life of BC’s Legendary Packer is a remarkable window into that astonishing period of the province’s history, and what a story it is!” —Stephen Hume “A compulsively readable novel, The Kissing Fence is a story about resilience and resistance in the face of a shameful, nearly forgotten episode in Canadian history. Insightful and sensitively told, it is a timely story that serves to remind us of the destructive multigenerational effects of the forced assimilation of children.” —Iona Whishaw “Let your soul come to rest in this haunting book as you take a quiet journey to a watershed that someone cherishes. Sweet Water examines our relationship to water in all its forms by the best poets among us and powerfully reminds us of our dependence on this precious life force. -

BC Labour Heritage Centre Oral History Project Interview with Kate

Kate Braid Interview Summary – November 8 2016 Page 1 of 8 BC Labour Heritage Centre Oral History Project Interview with Kate Braid Date: November 8, 2016 Location: Kate’s Home Interviewers: Bailey Garden, Ken Bauder Videographer: Bailey Garden Running Time: 01:40:44 Key Subjects: Al King; BC Institute of Technology [BCIT]; BC Regional Council of Carpenters; BC Federation of Labour [BC Fed]; Carpenter’s Union; Communist Party; Continuing Education [SFU]; Construction industry; Creative writing; Feminism; International Women’s Day [IWD]; Labour arts and culture; Labour education; Labour history; Labour school; Labour studies [faculty]; Malaspina University-College [now Vancouver Island University, VIU]; May Works [festival]; Oral history; Poetry; Politics; Sexual harassment; Simon Fraser University [SFU]; University of British Columbia [UBC]; Vancouver; Vancouver Island; Vancouver Industrial Writers Union; Women’s Committee [BC Fed]; Women in labour; Women’s rights; Women in trades; Women’s movement; Kate Braid is a labourer and poet, writing about her experiences as a female working in the male-dominated construction trades. 00:00 – 04:29 In the first section of the interview, introductions are made. Kate Braid was born in Calgary, Alberta on March 9, 1947. She was raised in Calgary until age 10, when her father got a job in Montreal. Her family lived in an Anglophone neighbourhood. She has memories of the FLQ crisis of the 1970s as she was still working in Quebec and dating a Francophone man at the time. She recalls understanding their frustration but feeling it was not her place as an Anglophone, and so she left the province. She recalls Expo 67, which was the first time she remembers feeling “truly Canadian”. -

Winter 2020 Catalogue

CAITLIN PRESS WHERE URBAN MEETS RURAL AND HOME OF DAGGER EDITIONS WINTER 2020 Chad Reimer Christina Myers ed. Susan Smith-Josephy & Irene Bjerky, C'eyxkn B.A. Thomas-Peter Yvonne Blomer ed. Betsy Warland Kim Goldberg PRAISE “Irene Kelleher and her family persevered with dignity in the face of racism; their stories link us to the fur trade, gold rush and settlement of the province. Indeed, these Invisible Generations helped forge a modern British Columbia. They should be celebrated, not forgotten.” —Mark Forsythe, former CBC British Columbia broadcaster “[In Escape to the Wild,] Hejlskov risks it all for what she believes in and gives us a rare and raw look at the fight it took to try and build a life in the wilderness.” —Nikki van Schyndel, author of Becoming Wild “Rising Tides uses words on climate change to name it, tame it and act as science tells us to, before it is too late—I commend Catriona Sandilands for bringing together this diverse group of people that honoured climate change through these words.” — Dr. Catherine Potvin, Canada Research Chair in Climate Change Mitigation and Tropical Forest (Tier 1) “[In On/Me,] Cunningham doesn’t pull her punches, but they are quick, stinging hits, captur- ing difficult realities, the in-between worlds of belonging and not, of bearing the assumptions that make us a part of a group or alone. The dangerous smoulder of her mind is masterfully harnessed to clarity, illuminating pain and turbulence without being tragic.” —Eden Robinson, author of Trickster Drift “[Baird’s] dazzling, precise lines reveal a vital poetics that grows out of ordinary landscapes to transform the text into a balm for insight, healing, and articulation. -

Bibliographie

Bibliographie Steven C. McNeil, avec la contribution de Lynn Brockington Abell, Walter, « Some Canadian Moderns », Magazine of Art, vol. 30, no 7 (juill. 1937), p. 422– 427. Abell, Walter, « New Books on Art Reviewed by the Editors, Klee Wyck by Emily Carr », Maritime Art, vol. 2, no 4 (avril–mai 1942), p. 137. Abell, Walter, « Canadian Aspirations in Painting », Culture, vol. 33, no 2 (juin 1942), p. 172– 182. Abell, Walter, « East is West – Thoughts on the Unity and Meaning of Contemporary Art », Canadian Art, vol. 11, no 2 (hiver 1954), p. 44–51, 73. Ackerman, Marianne, « Unexpurgated Emily », Globe and Mail (Toronto), 16 août 2003. Adams, James, « Emily Carr Painting Is Sold for $240,000 », Globe and Mail (Toronto), 28 nov. 2003. Adams, John, « …but Near Carr’s House Is Easy Street », Islander, supplément au Times- Colonist (Victoria), 7 juin 1992. Adams, John, « Emily Walked Familiar Routes », Islander, supplément au Times-Colonist (Victoria), 26 oct. 1993. Adams, John, « Visions of Sugar Plums », Times-Colonist (Victoria), 10 déc. 1995. Adams, Sharon, « Memories of Emily, an Embittered Artist », Edmonton Journal, 27 juill. 1973. Adams, Timothy Dow, « ‘Painting Above Paint’: Telling Li(v)es in Emily Carr’s Literary Self- Portraits », Journal of Canadian Studies, vol. 27, no 2 (été 1992), p. 37–48. Adeney, Jeanne, « The Galleries in January », Canadian Bookman, vol. 10, no 1 (janv. 1928), p. 5–7. Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Oil Paintings from the Emily Carr Trust Collection, cat. exp., Victoria, Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, 1958. Art Gallery of Ontario, Emily Carr: Selected Works from the Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, cat.