The Devonshire Collection Archives GB 2495 DF5 Papers of William

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chatsworth House

The Devonshire Collection Archives GB 2495 DF31 Papers of George Augustus Henry Cavendish, 1st Earl of Burlington of the 2nd creation (1754-1834), Lady Elizabeth Cavendish, Countess of Burlington (1760-1835), and members of the Compton Family 1717 - 1834 Created by Louise Clarke, Cataloguing Archivist, December 2014; revised by Fran Baker, January 2019, Chatsworth House Trust DF31: Papers of George Augustus Henry Cavendish, 1st Earl of Burlington of 2nd creation (1754-1834), Lady Elizabeth Cavendish, Countess of Burlington (1760-1835) and members of the Compton Family. Administrative/Biographical History: George Augustus Henry Cavendish, 1st Earl of Burlington, nobleman and politician, was born on 21 March 1754. He was the third son of William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire, and Charlotte Elizabeth Boyle, Baroness Clifford; his eldest brother William became 5th Duke of Devonshire. Styled Lord George Cavendish for most of his life, he attended Trinity College Cambridge, and subsequently became an MP. He was MP for Knaresborough from 1775-1780; for Derby from 1780 to 1796; and for Derbyshire from 1797 to 1831. His title was a revival of that held by his grandfather, Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington and 4th Earl of Cork. The Earl married Lady Elizabeth Compton, daughter of Charles Compton, 7th Earl of Northampton and Lady Ann Somerset, on 27 February 1782 at Trinity Chapel, Compton Street, St. George Hanover Square, London. They had six children: Caroline (d. 1867); William (1783- 1812); George Henry Compton (1784-1809); Anne (1787-1871); Henry Frederick Compton (1789-1873); and Charles Compton (1793-1863). The 1st Earl of Burlington died on 4 May 1834 at age 80 at Burlington House, Piccadilly, London. -

Catalogue of the Earl Marshal's Papers at Arundel

CONTENTS CONTENTS v FOREWORD by Sir Anthony Wagner, K.C.V.O., Garter King of Arms vii PREFACE ix LIST OF REFERENCES xi NUMERICAL KEY xiii COURT OF CHIVALRY Dated Cases 1 Undated Cases 26 Extracts from, or copies of, records relating to the Court; miscellaneous records concerning the Court or its officers 40 EARL MARSHAL Office and Jurisdiction 41 Precedence 48 Deputies 50 Dispute between Thomas, 8th Duke of Norfolk and Henry, Earl of Berkshire, 1719-1725/6 52 Secretaries and Clerks 54 COLLEGE OF ARMS General Administration 55 Commissions, appointments, promotions, suspensions, and deaths of Officers of Arms; applications for appointments as Officers of Arms; lists of Officers; miscellanea relating to Officers of Arms 62 Office of Garter King of Arms 69 Officers of Arms Extraordinary 74 Behaviour of Officers of Arms 75 Insignia and dress 81 Fees 83 Irregularities contrary to the rules of honour and arms 88 ACCESSIONS AND CORONATIONS Coronation of King James II 90 Coronation of King George III 90 Coronation of King George IV 90 Coronation of Queen Victoria 90 Coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra 90 Accession and Coronation of King George V and Queen Mary 96 Royal Accession and Coronation Oaths 97 Court of Claims 99 FUNERALS General 102 King George II 102 Augusta, Dowager Princess of Wales 102 King George III 102 King William IV 102 William Ewart Gladstone 103 Queen Victoria 103 King Edward VII 104 CEREMONIAL Precedence 106 Court Ceremonial; regulations; appointments; foreign titles and decorations 107 Opening of Parliament -

The Earl of Dartmouth As American Secretary 1773-1775

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1968 To Save an Empire: The Earl of Dartmouth as American Secretary 1773-1775 Nancy Briska anderson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation anderson, Nancy Briska, "To Save an Empire: The Earl of Dartmouth as American Secretary 1773-1775" (1968). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624654. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-tm56-qc52 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TO SAVE AH EMPIRE: jTHE EARL OP DARTMOUTH "i'i AS AMERICAN SECRETARY 1773 - 1775 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts By Nancy Brieha Anderson June* 1968 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Nancy Briska Anderson Author Approved, July, 1968: Ira Gruber, Ph.D. n E. Selby', Ph.D. of, B Harold L. Fowler, Ph.D. TO SAVE AN EMFIREs THE EARL OF DARTMOUTH AS AMERICAN SECRETARY X773 - 1775 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I first wish to express my appreciation to the Society of the Cincinnati for the fellowship which helped to make my year at the. -

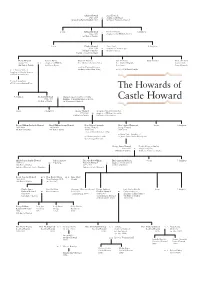

Howard Family Tree.Pdf

Charles Howard Anne Howard, 1629-1685 m. daughter of Edward, Created 1st Earl of Carlisle 1661 1st Baron Howard of Escrick 2 sons Edward Howard m. Elizabeth Uvedale, 3 daughters 1646-1692 daughter of Sir William Uvedale 2nd Earl of Carlisle 3 sons Charles Howard Anne Capel, 2 daughters 1669-1738 m. daughter of Arthur Capel, 3rd Earl of Carlisle 1st Earl of Essex (builder of Castle Howard) Henry Howard Isabella Byron, Elizabeth Howard, Anne Howard, Mary Howard Charles Howard, 1694-1758 m. 2. daughter of William, m. 1. Nicholas Lord Lechmere m. 1. Richard Ingram, Colonel in the 4th Earl of Carlisle 4th Baron Byron Lord Irwin Green Howards m. 2. Sir Thomas Robinson m. 1. Frances Spencer, (architect of the West Wing) m. 2. Col. William Douglas daughter of Charles Spencer, 3rd Earl of Sunderland 3 sons, 2 daughters, all but one predeceased him The Howards of 4 daughters Frederick Howard m. Margaret Caroline Leveson Gower, 1748-1825 daughter of Granville Leveson Gower, Castle Howard 5th Earl of Carlisle 1st Marquess of Stafford 3 sons 6 daughters George Howard Georgiana Dorothy Cavendish, 1773-1848 m. daughter of William Cavendish, 6th Earl of Carlisle 5th Duke of Devonshire George William Frederick Howard Revd William George Howard Hon. Edward Granville Hon. Charles Wentworth 2 sons 6 daughters 1802-1864 1808-1889 George Howard George Howard 7th Earl of Carlisle 8th Earl of Carlisle 1809-1880 1814-1879 (created Baron Lanerton 1874) m. Mary Parke, daughter of m. Diana, daughter of the Sir James Parke, Baron Wensleydale Hon. George Ponsonby George James Howard Rosalind Frances Stanley, 1843-1911 m. -

A Unique Experience with Albion Journeys

2020 Departures 2020 Departures A unique experience with Albion Journeys The Tudors & Stuarts in London Fenton House 4 to 11 May, 2020 - 8 Day Itinerary Sutton House $6,836 (AUD) per person double occupancy Eastbury Manor House The Charterhouse St Paul’s Cathedral London’s skyline today is characterised by modern high-rise Covent Garden Tower of London Banqueting House Westminster Abbey The Globe Theatre towers, but look hard and you can still see traces of its early Chelsea Physic Garden Syon Park history. The Tudor and Stuart monarchs collectively ruled Britain for over 200 years and this time was highly influential Ham House on the city’s architecture. We discover Sir Christopher Wren’s rebuilding of the city’s churches after the Great Fire of London along with visiting magnificent St Paul’s Cathedral. We also travel to the capital’s outskirts to find impressive Tudor houses waiting to be rediscovered. Kent Castles & Coasts 5 to 13 May, 2020 - 9 Day Itinerary $6,836 (AUD) per person double occupancy The romantic county of Kent offers a multitude of historic Windsor Castle LONDON Leeds Castle Margate treasures, from enchanting castles and stately homes to Down House imaginative gardens and delightful coastal towns. On this Chartwell Sandwich captivating break we learn about Kent’s role in shaping Hever Castle Canterbury Ightham Mote Godinton House English history, and discover some of its famous residents Sissinghurst Castle Garden such as Ann Boleyn, Charles Dickens and Winston Churchill. In Bodiam Castle a county famed for its castles, we also explore historic Hever and impressive Leeds Castle. -

Levens Hall & Gardens

LAKE DISTRICT & CUMBRIA GREAT HERITAGE 15 MINUTES OF FAME www.cumbriaslivingheritage.co.uk Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal Cumbria Living Heritage Members’ www.abbothall.org.uk ‘15 Minutes of Fame’ Claims Cumbria’s Living Heritage members all have decades or centuries of history in their Abbot Hall is renowned for its remarkable collection locker, but in the spirit of Andy Warhol, in what would have been the month of his of works, shown off to perfection in a Georgian house 90th birthday, they’ve crystallised a few things that could be further explored in 15 dating from 1759, which is one of Kendal’s finest minutes of internet research. buildings. It has a significant collection of works by artists such as JMW Turner, J R Cozens, David Cox, Some have also breathed life into the famous names associated with them, to Edward Lear and Kurt Schwitters, as well as having a reimagine them in a pop art style. significant collection of portraits by George Romney, who served his apprenticeship in Kendal. This includes All of their claims to fame would occupy you for much longer than 15 minutes, if a magnificent portrait - ‘The Gower Children’. The you visited them to explore them further, so why not do that and discover how other major piece in the gallery is The Great Picture, a interesting heritage can be? Here’s a top-to-bottom-of-the-county look at why they triptych by Jan van Belcamp portraying the 40-year all have something to shout about. struggle of Lady Anne Clifford to gain her rightful inheritance, through illustrations of her circumstances at different times during her life. -

The Life of William Ewart Gladstone (Vol 2 of 3) by John Morley

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Life of William Ewart Gladstone (Vol 2 of 3) by John Morley This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Life of William Ewart Gladstone (Vol 2 of 3) Author: John Morley Release Date: May 24, 2010, 2009 [Ebook 32510] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE LIFE OF WILLIAM EWART GLADSTONE (VOL 2 OF 3)*** The Life Of William Ewart Gladstone By John Morley In Three Volumes—Vol. II. (1859-1880) Toronto George N. Morang & Company, Limited Copyright, 1903 By The Macmillan Company Contents Book V. 1859-1868 . .2 Chapter I. The Italian Revolution. (1859-1860) . .2 Chapter II. The Great Budget. (1860-1861) . 21 Chapter III. Battle For Economy. (1860-1862) . 49 Chapter IV. The Spirit Of Gladstonian Finance. (1859- 1866) . 62 Chapter V. American Civil War. (1861-1863) . 79 Chapter VI. Death Of Friends—Days At Balmoral. (1861-1884) . 99 Chapter VII. Garibaldi—Denmark. (1864) . 121 Chapter VIII. Advance In Public Position And Other- wise. (1864) . 137 Chapter IX. Defeat At Oxford—Death Of Lord Palmer- ston—Parliamentary Leadership. (1865) . 156 Chapter X. Matters Ecclesiastical. (1864-1868) . 179 Chapter XI. Popular Estimates. (1868) . 192 Chapter XII. Letters. (1859-1868) . 203 Chapter XIII. Reform. (1866) . 223 Chapter XIV. The Struggle For Household Suffrage. (1867) . 250 Chapter XV. -

Mundella Papers Scope

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 6 - 9, MS 22 Title: Mundella Papers Scope: The correspondence and other papers of Anthony John Mundella, Liberal M.P. for Sheffield, including other related correspondence, 1861 to 1932. Dates: 1861-1932 (also Leader Family correspondence 1848-1890) Level: Fonds Extent: 23 boxes Name of creator: Anthony John Mundella Administrative / biographical history: The content of the papers is mainly political, and consists largely of the correspondence of Mundella, a prominent Liberal M.P. of the later 19th century who attained Cabinet rank. Also included in the collection are letters, not involving Mundella, of the family of Robert Leader, acquired by Mundella’s daughter Maria Theresa who intended to write a biography of her father, and transcriptions by Maria Theresa of correspondence between Mundella and Robert Leader, John Daniel Leader and another Sheffield Liberal M.P., Henry Joseph Wilson. The collection does not include any of the business archives of Hine and Mundella. Anthony John Mundella (1825-1897) was born in Leicester of an Italian father and an English mother. After education at a National School he entered the hosiery trade, ultimately becoming a partner in the firm of Hine and Mundella of Nottingham. He became active in the political life of Nottingham, and after giving a series of public lectures in Sheffield was invited to contest the seat in the General Election of 1868. Mundella was Liberal M.P. for Sheffield from 1868 to 1885, and for the Brightside division of the Borough from November 1885 to his death in 1897. -

Campbell List 88

Leabharlann Náisiúnta na hÉireann National Library of Ireland Collection List No. 88 PAPERS OF PAMELA LADY CAMPBELL AND HER FAMILY (MSS 40,024-40,031) (Accession No. 6048) Mostly family and other correspondence of Lady Pamela Campbell, daughter of Lord Edward Fitzgerald Compiled by Peter Kenny, Assistant Keeper, 2004 Introduction The Papers were acquired by the National Library of Ireland from Elizabeth Lady Campbell in January 2004 (Accession 6048). Pamela Fitzgerald, eldest daughter of Lord Edward Fitzgerald, the United Irishman, and his wife Pamela (née Sims, d. 1831), was born at Hamburg in 1796. She married Sir Guy Campbell on 21 November 1820. Sir Guy’s first wife, Frances Elizabeth (née Burgoyne), had died in 1818. They had an only child who was named after her mother. The marriage of Sir Guy and Lady Pamela produced eleven children. The Papers mostly consist of correspondence with family and friends. Additional papers of Lady Campbell and her family held by the National Library are listed in Collection List 46 (Lennox / Fitzgerald / Campbell Papers). I Papers of Sir Guy Campbell (d. 1849) For correspondence with his son Guy Colin Campbell (1824-1853) see MS 40,030 /1-3 below. For additional typescript copy letters see MS 40,028 /18-19 below. MS 40,024 /1 Army commissions. 1794-1849. 6 items. Includes his appointment as Deputy Quarter Master General to the forces in Ireland. MS 40,024 /2 Correspondence re medals and other awards. 1842-1849. 8 items. MS 40,024 /3 Campbell’s memorial to the Duke of York re his military service; with covering note and part of typed transcript of the memorial. -

Volunteer Role Description Ornamental/Kitchen Garden Volunteer

Volunteer Role Description Ornamental/Kitchen Garden Volunteer Role Title Ornamental/Kitchen Garden Volunteer Holker Hall Gardens, Cark-in-Cartmel, Grange-over-sands, Cumbria, LA11 Location 7PL Glyn Sherratt Main Contact Head Gardener Role function To support the garden team in delivering a high standard of horticulture in the ornamental and kitchen gardens. Main Activities • You will be assisting with the ‘day to day’ maintenance work in the gardens; primarily edging, weeding, planting, pruning, harvesting crops, leaf and grass collecting, and bulb planting. Desirable Qualities • A passion for horticulture and gardening. • Enjoy working in an outdoor situation and being part of a team. • To be reasonably physically fit (the role involves walking around, horticultural work and lifting regularly). • Have a basic knowledge of ornamental plants. Additional terms and information • We are looking for volunteers to help on a Wednesday and Friday from 10.30am to 3.30pm, with a half hour break for lunch. We kindly ask for a weekly commitment from our volunteers but can offer flexibility so it fits in around your life. • Volunteers will be issued with all the equipment needed to carry the work in the gardens, including gloves and steel toe-capped boots. • All Volunteers will receive an induction as well as Health & Safety training and other instruction appropriate to the tasks to be undertaken. The Benefits for You • Share and develop your skills and plant knowledge. • Gain experience to add to your CV. • Meet like-minded people and be part of an enthusiastic team. • Free entry to the garden for yourself and one other. The Next Step • If you wish to offer your time as a Garden Volunteer at Holker Hall, please complete the application form and email it to [email protected] . -

Jesse Collings, Agrarian Radical, 1880-1892

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 1-1-1975 Jesse Collings, agrarian radical, 1880-1892. David Murray Aronson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1 Recommended Citation Aronson, David Murray, "Jesse Collings, agrarian radical, 1880-1892." (1975). Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014. 1343. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_1/1343 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations 1896 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JESSE COLLINGS, AGRARIAN RADICAL, 1880-1892 A Dissertation Presented By DAVID MURRAY ARONSON Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 1975 History DAVID MURRAY ARONSON 1975 JESSE COLLINGS, AGRARIAN RADICAL, 1880-1892 A Dissertation By DAVID MURRAY AFONSON -Approved ss to style and content by Michael Wolff, Professor of English Franklin B. Wickwire, Professor of History Joyce BerVraan, Professor of History Gerald McFarland, Ch<- History Department August 1975 Jesse Collings, Agrarian Radical, 1880-1892 David M. Aronson, B,A., University of Rochester M.A. , Syracuse University Directed by: Michael Wolff Jesse Collings, although -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville.