HIGH-POWER and LOW-COMPLEXITY DUPLICATE BRIDGE METHODS for BABY BOOMERS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introducion to Duplicate

INTRODUCTION to DUPLICATE INTRODUCTION TO DUPLICATE BRIDGE This book is not about how to bid, declare or defend a hand of bridge. It assumes you know how to do that or are learning how to do those things elsewhere. It is your guide to playing Duplicate Bridge, which is how organized, competitive bridge is played all over the World. It explains all the Laws of Duplicate and the process of entering into Club games or Tournaments, the Convention Card, the protocols and rules of player conduct; the paraphernalia and terminology of duplicate. In short, it’s about the context in which duplicate bridge is played. To become an accomplished duplicate player, you will need to know everything in this book. But you can start playing duplicate immediately after you read Chapter I and skim through the other Chapters. © ACBL Unit 533, Palm Springs, Ca © ACBL Unit 533, 2018 Pg 1 INTRODUCTION to DUPLICATE This book belongs to Phone Email I joined the ACBL on ____/____ /____ by going to www.ACBL.com and signing up. My ACBL number is __________________ © ACBL Unit 533, 2018 Pg 2 INTRODUCTION to DUPLICATE Not a word of this book is about how to bid, play or defend a bridge hand. It assumes you have some bridge skills and an interest in enlarging your bridge experience by joining the world of organized bridge competition. It’s called Duplicate Bridge. It’s the difference between a casual Saturday morning round of golf or set of tennis and playing in your Club or State championships. As in golf or tennis, your skills will be tested in competition with others more or less skilled than you; this book is about the settings in which duplicate happens. -

International Teachers On-Line

International Teachers On-line International teachers are available to teach all levels of play. We teach Standard Italia (naturale 4 e 5a nobile), SAYC, the Two Over One system, Acol and Precision. - You can state your preference for which teacher you would like to work . Caitlin, founder of Bridge Forum, is an ACBL accredited teacher and author. She and Ned Downey recently co-authored the popular Standard Bidding with SAYC. As a longtime volunteer of Fifth Chair's popular SAYC team game, Caitlin received their Gold Star award in 2003. She has also beenhonored by OKbridge as "Angelfish" for her bridge ethics and etiquette. Caitlin has written articles for the ACBL's Bulletin and The Bridge Teacher as well as the American Bridge Teachers' Association ABTA Quarterly. Caitlin will be offering free classes on OKbridge with BRIDGE FORUM teacher Bill (athene) Frisby based on Standard Bidding with SAYC. For details of times and days, and to order the book, please check this website or email Caitlin at [email protected]. Ned Downey (ned-maui) is a tournament director, ACBL star teacher, and Silver Life Master with several regional titles to his credit. He is owner of the Maui Bridge Club and author of the novice text Just Plain Bridge as co-writing Standard Bidding with SAYC with Caitlin. Ned teaches regularly aboard cruise ships as well as in the Maui classroom and online. In addition to providing online individual and partnership lessons, he can be found on Swan Games Bridge (www.swangames.com) where he provides free supervised play groups on behalf of BRIDGE FORUM. -

Mirror (“Shadow”) (“Stolen Bid”) Doubles

“Mirror” (“Shadow”) (“Stolen Bid”) Doubles Mirror Doubles are sometimes used by Bridge Partnerships when a Player, poised to respond to Opener‟s strong, (15-17 HCP) 1-NT opening call, is confronted with a 2-level overcall by the would-be- Responder‟s, right-hand Opponent (RHO). Using “Mirror Doubles,” Responder‟s “double” under these circumstances, means, “Partner, my right-hand Opponent (RHO) has just stolen the bid that I was about to make. Had my RHO not done so, I was about to make the same bid that he/she just made.” For example, if a would-be Responder‟s right-hand Opponent overcalls 2D, and Responder “doubles,” it means that Responder was about to transfer to 2H, and so on. Opponent’s Overcall Meaning of the “Mirror Double” 2♣ Stayman 2♦ A Transfer to Hearts 2♥ A Transfer to Spades 2♠ By Partnership Agreement Today, although the use of “Mirror Doubles” remains as a staple of many recreational, local club Bridge Players, they tend not to be used by most of the better Players, with the exception of a “double,” following an interference call of “2C,” which is still, most often, used as a “Stayman” call; i.e., “Systems Are On,” and Opener is asked to respond as if Responder had invoked a Stayman, “2C,” initiating response. Other than this use of a “Mirror Double” over an interference call of “2C,” most of the better Players use a “double,” subsequent to 2-level, interference calls, above “2C,” as a far-more important, Negative or Penalty Double. The consensus seems to be that “Mirror Doubles” over interference calls at “2D” and above come at too high a cost, and that the loss of the ability to use a “double” as a Penalty or Take-Out, is too dear. -

Mirrors of Modernization: the American Reflection in Turkey

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Mirrors of Modernization: The American Reflection in urkT ey Begum Adalet University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Adalet, Begum, "Mirrors of Modernization: The American Reflection in urkT ey" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1186. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1186 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1186 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mirrors of Modernization: The American Reflection in urkT ey Abstract This project documents otherwise neglected dimensions entailed in the assemblage and implementations of political theories, namely their fabrication through encounters with their material, local, and affective constituents. Rather than emanating from the West and migrating to their venues of application, social scientific theories are fashioned in particular sites where political relations can be staged and worked upon. Such was the case with modernization theory, which prevailed in official and academic circles in the United States during the early phases of the Cold War. The theory bore its imprint on a series of developmental and infrastructural projects in Turkey, the beneficiary of Marshall Plan funds and academic exchange programs and one of the theory's most important models. The manuscript scrutinizes the corresponding sites of elaboration for the key indices of modernization: the capacity for empathy, mobility, and hospitality. In the case of Turkey the sites included survey research, the implementation of a highway network, and the expansion of the tourism industry through landmarks such as the Istanbul Hilton Hotel. -

Anaheim Angels?–Not Exactly

Presents Anaheim Angels?–Not Exactly Appeals at the 2000 Summer NABC Plus cases from the World Teams Olympiad Edited by Rich Colker ACBL Appeals Administrator Assistant Editor Linda Trent ACBL Appeals Manager CONTENTS Foreword ...................................................... iii The Expert Panel.................................................v Cases from Anaheim Tempo (Cases 1-21)...........................................1 Unauthorized Information (Cases 22-26)..........................75 Misinformation (Cases 27-43) ..................................90 Other (Case 44-48)..........................................142 Cases from the 11th World Teams Bridge Olympiad, Maastricht..........158 Tempo (Cases 49-50)........................................159 Misinformation (Cases 51-55) .................................165 Closing Remarks From the Expert Panelists..........................182 Closing Remarks From the Editor..................................186 The Panel’s Director and Committee Ratings .........................191 NABC Appeals Committee .......................................192 Abbreviations used in this casebook: AI Authorized Information AWMW Appeal Without Merit Warning LA Logical Alternative MI Misinformation PP Procedural Penalty UI Unauthorized Information i ii FOREWORD We continue our presentation of appeals from NABC tournaments. As always, our goal is to inform, provide constructive criticism, and foster change (hopefully) for the better in a manner that is entertaining, instructive and stimulating. The ACBL -

Beat Them at the One Level Eastbourne Epic

National Poetry Day Tablet scoring - the rhyme and reason Rosen - beat them at the one level Byrne - Ode to two- suited overcalls Gold - time to jump shift? Eastbourne Epic – winners and pictures English Bridge INSIDE GUIDE © All rights reserved From the Chairman 5 n ENGLISH BRIDGE Major Jump Shifts – David Gold 6 is published every two months by the n Heather’s Hints – Heather Dhondy 8 ENGLISH BRIDGE UNION n Bridge Fiction – David Bird 10 n Broadfields, Bicester Road, Double, Bid or Pass? – Andrew Robson 12 Aylesbury HP19 8AZ n Prize Leads Quiz – Mould’s questions 14 n ( 01296 317200 Fax: 01296 317220 Add one thing – Neil Rosen N 16 [email protected] EW n Web site: www.ebu.co.uk Basic Card Play – Paul Bowyer 18 n ________________ Two-suit overcalls – Michael Byrne 20 n World Bridge Games – David Burn 22 Editor: Lou Hobhouse n Raggett House, Bowdens, Somerset, TA10 0DD Ask Frances – Frances Hinden 24 n Beat Today’s Experts – Bird’s questions 25 ( 07884 946870 n [email protected] Sleuth’s Quiz – Ron Klinger’s questions 27 n ________________ Bridge with a Twist – Simon Cochemé 28 n Editorial Board Pairs vs Teams – Simon Cope 30 n Jeremy Dhondy (Chairman), Bridge Ha Ha & Caption Competition 32 n Barry Capal, Lou Hobhouse, Peter Stockdale Poetry special – Various 34 n ________________ Electronic scoring review – Barry Morrison 36 n Advertising Manager Eastbourne results and pictures 38 n Chris Danby at Danby Advertising EBU News, Eastbourne & Calendar 40 n Fir Trees, Hall Road, Hainford, Ask Gordon – Gordon Rainsford 42 n Norwich NR10 3LX -

Qthe Bidding

ONBOARD CREDIT £200 UP TO WHEN BOOKED BY 15TH OCTOBER Pyramids of Giza, Egypt Minerva Lofoten Islands, Norway Alhambra, Spain Exceptional value Bridge cruising aboard Minerva At Swan Hellenic we will always go further and delve that bit deeper. Our on board guest speakers and inclusive excursions ashore take you behind civilisations both ancient and modern, with fascinating results. You will travel in country-house style with around 320 other like-minded passengers. Choose to dine in the restaurant of your choice and in the company of your friends and you will still be assured of exceptional value for money, including all tips on board and ashore. Travel with a truly great British company, established in 1954, and enjoy an experience that will live with you forever. All passengers who have booked and registered through will be eligible to partake in the late afternoon bridge sessions, held on days when the ship is at sea. There is no bridge supplement as, like most of the excursions, it is included in the price. Mr Bridge actively encourages singles to join the party and they will always be found a partner for a game. Departs Cruise SPRING 2012 11 Apr EGYPT AND THE LEVANT 15 days from £2,255pp YOUR VOYAGE Sharm el Sheikh, El Sokhna, Alexandria, Tartous, Latakia, Antalya, Fethiye, Santorini, Piraeus INCLUDES: 25 Apr A CLASSIC SPRING 14 days from £2,155pp Piraeus, Corinth Canal, Itea, Katakolon, Argostoli, Preveza, Kotor, Korcula, Dubrovnik, Palermo, • Exclusive Mr Bridge drinks Civitavecchia parties* 8 May A MEDITERRANEAN MASTERPIECE 15 days from £1,990pp Civitavecchia, Portoferraio, Nice, Port Vendres, Mahon, Malaga, Cadiz, Portimao, Vigo, • Travel in country-house style St. -

The Maritime Club a Relay Precision System

The Maritime Club A Relay Precision System By Ethan Macaulay & Aled Iaboni Updated May, 2020 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents ......................................................................................................... 2 General Approach - Precision ....................................................................................... 5 The 1♣ Opening ........................................................................................................... 6 General Structure ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 After 1♣- ........................................................................................................................................................................ 6 After a Negative Response to 1♣ ......................................................................................................................... 7 After 1♣-1♦ ................................................................................................................................................................... 7 After 1♣-1♦-1♥ ............................................................................................................................................................ 7 After 1♣-1♦-1♥-1♠ ..................................................................................................................................................... 8 After 1♣-1♦-1♥-1NT ................................................................................................................................................ -

Pages 1-21 As

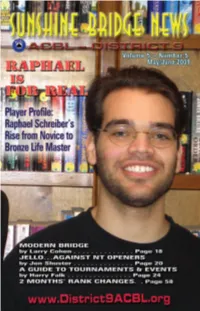

2 ACBL District 9 www.District9ACBL.org 3 SBN Vol 5 No 4:~SBN Vol 5 No 2 3/17/09 1:32 PM Page 8 SBN Vol 5 No 4:~SBN Vol 5 No 2 4/20/09 3:41 PM Page 9 Palm Beach Gardens Schedule of Events Regional Tournament ALL TIMES ARE PM UNLESS STATED OTHERWISE PGA 1:00 Charity Open Pairs Monday 7:00 Charity Open Pairs PGA National Resort & Spa May 25 MAY 400 Avenue of Champions, Palm Beach Gardens 7:00 Bracketed Open KO’s, Round 1 (cont’d Tue. 9:00 am, 1:00 & 7:00) 9:00 am Morning Side Game Series (1 of 5) 10:00 am & 3:00 Stratified Senior Pairs (two-session event) (800) 633-9150 • (561) 627-2000 10:00 am 299er Pairs (single-session) 25-31 Tuesday 1:00 & 7:00 Primetime KO’s I, Rounds 1 & 2 (cont’d 1:00 & 7:00 Wed.) May 26 1:00 & 7:00 Stratified Open Pairs (two-session event) 1:00 Side Game Series I (1 of 6) HOSTS 3:00 299er Pairs (single-session) (Notice New Strata) 7:00 Side Game Series I (2 of 6) Bob Parlin STRATA 7:00 Stratified Swiss Teams (single-session) Open & Senior Events 239-774-1139 9:00 am Morning KO’s, Round 1 (cont’d 9:00 am Thu., Fri., Sat.) A=2000+ B=750-2000 C=0-750 9:00 am Morning Side Game Series (2 of 5) [email protected] 10:00 am & 3:00 Stratified Senior Pairs (two-session event) 299er Events 10:00 am 299er Pairs (single-session) Jayne Thomas A=200-300, B=100-200, C=0-100 Wednesday 1:00 & 7:00 Primetime KO’s II, Rounds 1 & 2 (cont’d 1:00 & 7:00 Thu.) May 27 1:00 & 7:00 Stratified Open Pairs (two-session event) 813-727-5796 Strata May Be Changed At Director’s 1:00 Side Game, Series I (3 of 6) Discretion 3:00 299er Pairs (single-session) -

Editor Chris Buckley Contact Details Tel: 570

Editor Chris Buckley Contact details Tel: 570 3492 or 021 154 4321 Email: [email protected] Marvellous Mavis Marks Milestone A capacity crowd of members turned up on Tuesday 8th October to help Mavis celebrate her special day. It’s hard to believe that Mavis is 100 years old! Resplendent in her colourful outfit and specially decorated chair and room, songs were sung to her, glowing comments were attributed to her and a special cake was served. Humble as ever, Mavis took the occasion in her stride and played to her audience making witty comments and receiving her guests as they lined up to offer congratulations. Two of Mavis’ four children played bridge with her and joined in the special celebration. Mavis credits her longevity to her stout Finnish, German and English ancestry and a can-do attitude. Born in Taupiri, she was a keen sportswoman playing netball, basketball, tennis and golf…as well as a savvy game of bridge! Her children, 12 grandchildren, 33 great-grandchildren, and 2 great- great-grandchildren keep her young too. These key events have occurred over Mavis’ life: 1930 – The Great Depression 1931 – Hawkes Bay earthquake destroys much of Napier and Hastings 1940 – The Holocaust 1941 – Pearl Harbour 1945 – VE Day 1953 – Sir Edmund Hillary & Sherpa Tenzing Norgay conquer Mt Everest 1955 – Vietnam War 1960 – Television transmission begins in NZ 1961 – First man in space 2003 – Iraq War Christmas Party Can you believe that the Christmas season is imminent! Where did the year go?? Anyway to assist with your planning and costume preparation, the letter we all need to dress to is ‘E’. -

BIDDING CONVENTIONS and TECHNIQUES 1

BIDDING CONVENTIONS and TECHNIQUES CONTENTS 2 . OPENING ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 19 BALANCING ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 54 BIDDING NOTRUMP FIRST ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 53 BIDDING OVER [1./ – P – 1NT …?] ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 48 BIDDING OVER PREEMPTS ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ 49 COMPETING AT THE 5-LEVEL --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 57 COMPETING OVER A BIG CLUB (PRECISION) OPENING ----------------------------------------------------------------------- 58 COMPETITIVE BIDDING SUMMARY ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 29 CONSTRUCTIVE RAISES ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 63 CUE BID SUMMARY --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 31 DEFENSE RULES -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 80 DEFENSE ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

![OPENING • 1C — [2S] — X (I Or Borh Minors) Openings Third](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5464/opening-1c-2s-x-i-or-borh-minors-openings-third-1735464.webp)

OPENING • 1C — [2S] — X (I Or Borh Minors) Openings Third

I'hav~y Norris ci- ~~~i~i~ lV)n~a~~n SPECIAL DOUBLES NOTRUMP OVERCALLS GENERAL After overcall: Penalty APPROACH ~~~~OPENING Direct: 15 to 18 HCP Systems on'~ Neg.`~ thru 2S (only in some auctions) 5551. Our own system. Balanced hands w/o 5 a card major open 1~. Transfer Expected Min Length: 5 ❑ 4 ❑ 3 ❑ 2~~~1 ❑ ga~~cing: 10 to 14 / m; 12 to 16 / M Artif. •1C —[1 D or 1 H]— X (stolen bid = xfr) responses to lip. Many conv. responses. Many rebids by both aze transfers. Describe: dump to 2NT: Minors ❑ 2 Lowest either natural or balanced. Includes all bal. w/o a 5 card major. •1D — [1 H]— X balanced, (GF, 4-5 ~) Two Over One: GF ❑ Other ~((2~ is artif. GFj(2t is conv., always < GF) •Bal.: 11-14 or 18-20 •unbal, with primary 4(5+) •a114441s •1C — [2S] — X(I or borh minors) JUMP OVERCALL: VERY LIGHT: Openings Responsive: thru 2S Maximal Third hand, Overcalls ❑ Preempts ❑ RESPONSES Stron Intermediate Weak Support: Dblx; thru 2PS Redbl ~ ~ FORCING OPENING: 12 ' ~~~~~~ Nat Two bids Other~(2~, NAMYATS~ 1♦ Transfer, 4+ r. May have a longer minor. I GF always unbal. Card-showing~. OPENING Min. Offshape T/O~ PREEMPTS Note: All "HCP ranges" aze approximate. We often "adjust," more often up. ~~~~ Transfer,4+ s. May have a longer minor. I GF always unbal. Other: Pass-double inversion (X =doubt) 3/4-bids: Sound 0 light, very light ❑ 1~ Artif., 0-12. Almost all < GF hands w/o a 4+Major. Bal. or unbal. SIMPLE OVERCALL DEFENSE VS NOTRUMP NT OPENINGS 1 NT GF.