We Remember Lest the World Forget 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No Justice for Journalists in Ukraine, Belarus and Russia September 2011

No Justice for Journalists in Ukraine, Belarus and Russia September 2011 ARTICLE 19 Free Word Centre 60 Farringdon Road London EC1R 3GA United Kingdom Tel: +44 20 7324 2500 Fax: +44 20 7490 0566 E-mail: [email protected] www.article19.org International Media Support (IMS) Nørregarde 18, 2nd floor 1165 Copenhagen K Denmark Tel: +45 88 32 7000 Fax: +45 33 12 0099 E-mail: [email protected] www.i-m-s.dk ISBN: 978-1-906586-27-0 © ARTICLE 19 and International Media Support (IMS), London and Copenhagen, August 2011 This work is provided under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 2.5 licence. You are free to copy, distribute and display this work and to make derivative works, provided you: 1) give credit to ARTICLE 19 and International Media Support (IMS); 2) do not use this work for commercial purposes; 3) distribute any works derived from this publication under a licence identical to this one. To access the full legal text of this licence, please visit: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ legalcode. ARTICLE 19 and International Media Support (IMS) would appreciate receiving a copy of any materials in which information from this report is used. This report was written and published within the framework of a project supported by the International Media Support (IMS) Media and Democracy Programme for Central and Eastern Europe and the Caucasus. It was compiled and written by Nathalie Losekoot, Senior Programme Officer for Europe at ARTICLE 19 and reviewed by JUDr. Barbora Bukovskà, Senior Director for Law at ARTICLE 19 and Jane Møller Larsen, Programme Coordinator for the Media and Democracy Unit at International Media Support (IMS). -

MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series

MCA 700 Discography by David Edwards, Mike Callahan & Patrice Eyries © 2018 by Mike Callahan MCA-700 Midline/Reissue Series: By the time the reissue series reached MCA-700, most of the ABC reissues had been accomplished in the MCA 500-600s. MCA decided that when full price albums were converted to midline prices, the albums needed a new number altogether rather than just making the administrative change. In this series, we get reissues of many MCA albums that were only one to three years old, as well as a lot of Decca reissues. Rather than pay the price for new covers and labels, most of these were just stamped with the new numbers in gold ink on the front covers, with the same jackets and labels with the old catalog numbers. MCA 700 - We All Have a Star - Wilton Felder [1981] Reissue of ABC AA 1009. We All Have A Star/I Know Who I Am/Why Believe/The Cycles Of Time//Let's Dance Together/My Name Is Love/You And Me And Ecstasy/Ride On MCA 701 - Original Voice Tracks from His Greatest Movies - W.C. Fields [1981] Reissue of MCA 2073. The Philosophy Of W.C. Fields/The "Sound" Of W.C. Fields/The Rascality Of W.C. Fields/The Chicanery Of W.C. Fields//W.C. Fields - The Braggart And Teller Of Tall Tales/The Spirit Of W.C. Fields/W.C. Fields - A Man Against Children, Motherhood, Fatherhood And Brotherhood/W.C. Fields - Creator Of Weird Names MCA 702 - Conway - Conway Twitty [1981] Reissue of MCA 3063. -

Cercle Hermaphroditos5

Cercle Hermaphroditos By Shualee Cook Cast: Laureline Reeves - trans female, 38, mastermind and ringleader of the Cercle Hermaphroditos Ambrose Carlton - trans male, mid 20s, prominent "gynander" looking to marry on his own terms Bertram Templeton - cis male, 30s, Ambrose's brother, active mover in the banking world Jennie June - trans female, 22, college student and aspiring author Phyllis Angevine - trans female, 33, queen of the Rialto "androgynes" Plum Gardner - trans female, 23, clerk by day, ingenue by night Officer Leahy - cis male, 30's, an old hand at the beat Officer Clark - cis male, late 20's, straight laced and by the book A Gentleman and a Man, played by the actors playing Leahy and Clark Setting: Rooms of the Cercle Hermaphroditos, an apartment on the upper floors of Columbia Hall, 32 Cooper Square, New York City; the ballroom below; a park bench on the Rialto Time: Fall of 1895 Note: Throughout the script, italics isolate private conversations between two people from the chatter around them. 1. Act One SCENE ONE The rooms of the Cercle Hermaphroditos. Stage left and center, the main parlor. Stylish, tastefully decorated, with the occasional flamboyant touch. Stage right, the kitchen. Bright and cheerful. In the parlor, LAURELINE REEVES, in a dress that manages to be elegant and sensible all at once, arranges a table for tea, taking pleasure in precision. A knock at the door. LAURELINE Everything in its place, and just in time. (to the door) Yes? VOICE Carlton to see Mr. Roland Reeves? LAURELINE Alone? VOICE As we'd discussed. Laureline looks through the door's peephole, is satisfied. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Title of Thesis: ABSTRACT CLASSIFYING BIAS

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis Directed By: Dr. David Zajic, Ph.D. Our project extends previous algorithmic approaches to finding bias in large text corpora. We used multilingual topic modeling to examine language-specific bias in the English, Spanish, and Russian versions of Wikipedia. In particular, we placed Spanish articles discussing the Cold War on a Russian-English viewpoint spectrum based on similarity in topic distribution. We then crowdsourced human annotations of Spanish Wikipedia articles for comparison to the topic model. Our hypothesis was that human annotators and topic modeling algorithms would provide correlated results for bias. However, that was not the case. Our annotators indicated that humans were more perceptive of sentiment in article text than topic distribution, which suggests that our classifier provides a different perspective on a text’s bias. CLASSIFYING BIAS IN LARGE MULTILINGUAL CORPORA VIA CROWDSOURCING AND TOPIC MODELING by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Gemstone Honors Program, University of Maryland, 2018 Advisory Committee: Dr. David Zajic, Chair Dr. Brian Butler Dr. Marine Carpuat Dr. Melanie Kill Dr. Philip Resnik Mr. Ed Summers © Copyright by Team BIASES: Brianna Caljean, Katherine Calvert, Ashley Chang, Elliot Frank, Rosana Garay Jáuregui, Geoffrey Palo, Ryan Rinker, Gareth Weakly, Nicolette Wolfrey, William Zhang 2018 Acknowledgements We would like to express our sincerest gratitude to our mentor, Dr. -

ZRBG – Ghetto-Liste (Stand: 01.08.2014) Sofern Eine Beschäftigung I

ZRBG – Ghetto-Liste (Stand: 01.08.2014) Sofern eine Beschäftigung i. S. d. ZRBG schon vor dem angegebenen Eröffnungszeitpunkt glaubhaft gemacht ist, kann für die folgenden Gebiete auf den Beginn der Ghettoisierung nach Verordnungslage abgestellt werden: - Generalgouvernement (ohne Galizien): 01.01.1940 - Galizien: 06.09.1941 - Bialystok: 02.08.1941 - Reichskommissariat Ostland (Weißrussland/Weißruthenien): 02.08.1941 - Reichskommissariat Ukraine (Wolhynien/Shitomir): 05.09.1941 Eine Vorlage an die Untergruppe ZRBG ist in diesen Fällen nicht erforderlich. Datum der Nr. Ort: Gebiet: Eröffnung: Liquidierung: Deportationen: Bemerkungen: Quelle: Ergänzung Abaujszanto, 5613 Ungarn, Encyclopedia of Jewish Life, Braham: Abaújszántó [Hun] 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Kassa, Auschwitz 27.04.2010 (5010) Operationszone I Enciklopédiája (Szántó) Reichskommissariat Aboltsy [Bel] Ostland (1941-1944), (Oboltsy [Rus], 5614 Generalbezirk 14.08.1941 04.06.1942 Encyclopedia of Jewish Life, 2001 24.03.2009 Oboltzi [Yid], Weißruthenien, heute Obolce [Pol]) Gebiet Vitebsk Abony [Hun] (Abon, Ungarn, 5443 Nagyabony, 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Encyclopedia of Jewish Life 2001 11.11.2009 Operationszone IV Szolnokabony) Ungarn, Szeged, 3500 Ada 16.04.1944 13.07.1944 Braham: Enciklopédiája 09.11.2009 Operationszone IV Auschwitz Generalgouvernement, 3501 Adamow Distrikt Lublin (1939- 01.01.1940 20.12.1942 Kossoy, Encyclopedia of Jewish Life 09.11.2009 1944) Reichskommissariat Aizpute 3502 Ostland (1941-1944), 02.08.1941 27.10.1941 USHMM 02.2008 09.11.2009 (Hosenpoth) Generalbezirk -

Rotefan Eloyan Markosovish Prisoner Petition Letter to Comrade

See also Vladislav Eloyan and Michael McKibben with Joseph Lipsius and George West. "Eloyan Rotefan Marcosovich. A Newly Discovered 69th Inf. Div Legacy of Spirit, Resilience and Valor. 69th Inf Div 271st Inf Reg AT Co". The U.S. Army 69th Infantry Division Association Website. July 4, 2010. Petition Letter <http://www.69th-infantry-division.com/whowhere/photoo3-Eloyan- Rotefan-Marcosovich.html>. Last updated December 21, 2010. Original Russian Petition Letter follows. From: Eloyan Rotefan Markosovich, Prisoner To: Comrade Malenkov, Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR1 Date: 22 October 1953 I would like to introduce myself and describe the recent events in Norilsk briefly. I was born in Erevan in 1925 and moved to Moscow with by brother and father in 1930. In 1941 I finished seven years of education in school No. 279. In July 1941 at only 15 years old I joined the Red Army as a volunteer in an armored cavalry battalion of the 13th Rifle Division. On 22 October I was severely wounded near Vyazma city and picked up by an army ambulance from the village of Proletarskoe. A week later our ambulance detail was captured by Germans. After I had partially recovered, I escaped on crutches and wandered into the Smolensk district. Since I was only 16 years old, the Germans didn’t ask me for documents, so I roamed from village to village with some of my friends. My wounds healed slowly, making it difficult to walk for the longest time. I was once sheltered by Ivan Mikheev at his house in the village of Kamentshiki. -

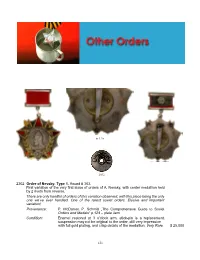

2302 Order of Nevsky. Type 1. Award # 363. First Variation of the Very First Issue of Orders of A. Nevsky, with Center Medallion Held by 2 Rivets from Reverse

to 1.5x 2302 2302 Order of Nevsky. Type 1. Award # 363. First variation of the very first issue of orders of A. Nevsky, with center medallion held by 2 rivets from reverse. There are only handful of orders of this variation observed, with this piece being the only one we’ve ever handled. One of the rarest soviet orders. Elusive and important variation! Provenance: P. McDaniel, P. Schmitt „The Comprehensive Guide to Soviet Orders and Medals“ p.124 – plate item. Condition: Enamel restored at 3 o’clock arm, stick-pin is a replacement, suspension may not be original to the order, still very impressive with full gold plating, and crisp details of the medallion. Very Rare $ 25,000 121 2303 2303 Order of Nevsky. Type 2. Award # 9464. Original silver nut. Comes with copies of official research from Ministry of Defense of Russian Federation – awarded to Guards Captain V. Volosyankin, company commander of 131st Guards Rifle Regiment, 45th Rifle Division, 30th Guards Rifle Corps. English translation attached. Also comes with Certificate of Authenticity from Paul McDaniel (6 out of 10 condition rating). Condition: Light patina, some red enamel replaced, about 50% of the gold-plating remains $ 4,000 2304 2304 Order of Nevsky. Type 3. Award # 12370. Variation 3. Early "ìîíåòíûé äâîð" issue. Original silver nut. Comes with copies of official research from Ministry of Defense of Russian Federation – awarded to Guards Major S. Zinakov, commander of special armor train detachment. English translation attached. Condition: Dark patina with full gold-plating remaining. Superb $ 4,000 2305 122 2305 Complete documented group of Jun. -

Parallel Journeys:Parallel Teacher’S Guide

Teacher’s Parallel Journeys: The Holocaust through the Eyes of Teens Guide GRADES 9 -12 Phone: 470 . 578 . 2083 historymuseum.kennesaw.edu Parallel Journeys: The Holocaust through the Eyes of Teens Teacher’s Guide Teacher’s Table of Contents About this Teacher’s Guide.............................................................................................................. 3 Overview ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Georgia Standards of Excellence Correlated with These Activities ...................................... 5 Guidelines for Teaching about the Holocaust .......................................................................... 12 CORE LESSON Understanding the Holocaust: “Tightening the Noose” – All Grades | 5th – 12th ............................ 15 5th Grade Activities 1. Individual Experiences of the Holocaust .......................................................................... 18 2. Propaganda and Dr. Seuss .................................................................................................. 20 3. Spiritual Resistance and the Butterfly Project .................................................................. 22 4. Responding to the St. Louis ............................................................................................... 24 5. Mapping the War and the Holocaust ................................................................................. 25 6th, 7th, and 8th Grade Activities -

Lobach the Sacred Lakes of the Dvina Region (Northwest Belarus)

THE SACRED LAKES OF THE DVINA REGION (NORTHWEST BELARUS) ULADZIMER LOBACH BALTICA 15 BALTICA Abstract The subject of research is the sacral geography of the Dvina region (in northwest Belarus), the sacred lakes situated in this region, and place-legends about vanished churches relating to these lakes. The author bases his research on the analytical method, and interprets folkloric sources, historical facts and data collected during ethnographic field trips. The main con- clusion of the article attests to the fact that place-legends about a vanished church (they relate to the majority of the lakes) ARCHAEOLOGIA indicate the sacrality of these bodies of water. In the past, sacrality might have contained two closely interrelated planes: an archaic one, which originated from pre-Christian times, and that of the Early Middle Ages, related to the baptism of the people of the Duchy of Polotsk. Key words: Belarusian Dvina region, sacral geography, sacred lakes, ancient religion, Christianisation, folklore. During ethnographic field trips organised by research- been found (four in the Homiel, and three in the Mahil- I ers from Polotsk University between 1995 and 2008, iou region). It should also be pointed out that the con- NATURAL HOLY a large amount of folklore data about lakes that still centration of lakes in the Dvina region (no more than PLACES IN ARCHAEOLOGY occupy a special place in the traditional vision of the 35 per cent of all the lakes in Belarus) is not as high AND world of the rural population was recorded. This means as is commonly supposed. Due to popular belief, the FOLKLORE IN THE BALTIC objects of ‘sacral geography’, which for the purposes region is often referred to as ‘the land of blue lakes’. -

Orders, Medals and Decorations

Orders, Medals and Decorations To be sold by auction at: Sotheby’s, in the Lower Grosvenor Gallery The Aeolian Hall, Bloomfield Place New Bond Street London W1A 2AA Day of Sale: Thursday 1 December 2016 at 12.00 noon and 2.30 pm Public viewing: Nash House, St George Street, London W1S 2FQ Monday 28 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Tuesday 29 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Wednesday 30 November 10.00 am to 4.30 pm Or by previous appointment. Catalogue no. 83 Price £15 Enquiries: Paul Wood, David Kirk or James Morton Cover illustrations: Lot 239 (front); lot 344 (back); lot 35 (inside front); lot 217 (inside back) Tel.: +44 (0)20 7493 5344 Fax: +44 (0)20 7495 6325 Email: [email protected] Website: www.mortonandeden.com This auction is conducted by Morton & Eden Ltd. in accordance with our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue. All questions and comments relating to the operation of this sale or to its content should be addressed to Morton & Eden Ltd. and not to Sotheby’s. Online Bidding This auction can be viewed online at www.the-saleroom.com, www.numisbids.com and www.sixbid.com. Morton & Eden Ltd offers an online bidding service via www.the-saleroom.com. This is provided on the under- standing that Morton & Eden Ltd shall not be responsible for errors or failures to execute internet bids for reasons including but not limited to: i) a loss of internet connection by either party; ii) a breakdown or other problems with the online bidding software; iii) a breakdown or other problems with your computer, system or internet connec- tion. -

BELARUS: Conscientious Objector Jailed

FORUM 18 NEWS SERVICE, Oslo, Norway http://www.forum18.org/ The right to believe, to worship and witness The right to change one's belief or religion The right to join together and express one's belief This article was published by F18News on: 1 February 2010 BELARUS: Conscientious objector jailed By Felix Corley, Forum 18 News Service <http://www.forum18.org> Ivan Mikhailov, a Messianic Jew, has today (1 February) had a three-month jail term imposed on him by a court in Belarus for refusing compulsory military service. His brother-in-law told Forum 18 News Service that "The sentence has nothing to do with justice." His lawyer, Svetlana Gorbatok, argued that the absence of an Alternative Service Law is not a legal basis for violating Mikhailov's rights. He has been in pre-trial detention since 15 December 2009, and must serve another six weeks unless he wins an appeal he will make. Also present in court was Mikhail Pashkevich of 'For Alternative Civilian Service', which has launched a civic society petition calling for civilian alternative service. Prosecutor Aleksandr Cherepovich, asked by Forum 18 who had suffered from refusal to undertake compulsory military service, replied: "The state." Meanwhile, the launch of a CD compilation of Christian songs at a Catholic church has been stopped under state pressure. Senior religious affairs official Alla Ryabitseva angrily told Forum 18 that: "Concerts don't take place in churches." The family of Ivan Mikhailov, a Messianic Jew, condemned a three-month prison term handed him today (1 February) by a court in the Belarusian capital Minsk for refusing compulsory military service.