Union Park Hotel 1519 W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chicago Neighborhood Resource Directory Contents Hgi

CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD [ RESOURCE DIRECTORY san serif is Univers light 45 serif is adobe garamond pro CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY CONTENTS hgi 97 • CHICAGO RESOURCES 139 • GAGE PARK 184 • NORTH PARK 106 • ALBANY PARK 140 • GARFIELD RIDGE 185 • NORWOOD PARK 107 • ARCHER HEIGHTS 141 • GRAND BOULEVARD 186 • OAKLAND 108 • ARMOUR SQUARE 143 • GREATER GRAND CROSSING 187 • O’HARE 109 • ASHBURN 145 • HEGEWISCH 188 • PORTAGE PARK 110 • AUBURN GRESHAM 146 • HERMOSA 189 • PULLMAN 112 • AUSTIN 147 • HUMBOLDT PARK 190 • RIVERDALE 115 • AVALON PARK 149 • HYDE PARK 191 • ROGERS PARK 116 • AVONDALE 150 • IRVING PARK 192 • ROSELAND 117 • BELMONT CRAGIN 152 • JEFFERSON PARK 194 • SOUTH CHICAGO 118 • BEVERLY 153 • KENWOOD 196 • SOUTH DEERING 119 • BRIDGEPORT 154 • LAKE VIEW 197 • SOUTH LAWNDALE 120 • BRIGHTON PARK 156 • LINCOLN PARK 199 • SOUTH SHORE 121 • BURNSIDE 158 • LINCOLN SQUARE 201 • UPTOWN 122 • CALUMET HEIGHTS 160 • LOGAN SQUARE 204 • WASHINGTON HEIGHTS 123 • CHATHAM 162 • LOOP 205 • WASHINGTON PARK 124 • CHICAGO LAWN 165 • LOWER WEST SIDE 206 • WEST ELSDON 125 • CLEARING 167 • MCKINLEY PARK 207 • WEST ENGLEWOOD 126 • DOUGLAS PARK 168 • MONTCLARE 208 • WEST GARFIELD PARK 128 • DUNNING 169 • MORGAN PARK 210 • WEST LAWN 129 • EAST GARFIELD PARK 170 • MOUNT GREENWOOD 211 • WEST PULLMAN 131 • EAST SIDE 171 • NEAR NORTH SIDE 212 • WEST RIDGE 132 • EDGEWATER 173 • NEAR SOUTH SIDE 214 • WEST TOWN 134 • EDISON PARK 174 • NEAR WEST SIDE 217 • WOODLAWN 135 • ENGLEWOOD 178 • NEW CITY 219 • SOURCE LIST 137 • FOREST GLEN 180 • NORTH CENTER 138 • FULLER PARK 181 • NORTH LAWNDALE DEPARTMENT OF FAMILY & SUPPORT SERVICES NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY WELCOME (eU& ...TO THE NEIGHBORHOOD RESOURCE DIRECTORY! This Directory has been compiled by the Chicago Department of Family and Support Services and Chapin Hall to assist Chicago families in connecting to available resources in their communities. -

Table of Contents

The Newberry Library Guide to Chicago Church and Synagogue Records Rev. 4/10/2014 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS The Newberry Library .............................................................................................................. 1 Guide to Chicago Church and Synagogue Records .......................................................... 1 Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................... 2 CHICAGO CHURCHES AND SYNAGOGUES—GENERAL ................................................ 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 5 Archives ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Family History Library .......................................................................................................... 5 Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center .......................................................... 5 Books and publications ........................................................................................................... 5 AFRICAN-AMERICAN CHURCHES ......................................................................................... 7 Denominational web sites ....................................................................................................... 7 Congregations.......................................................................................................................... -

Developed by Contents

DEVELOPED BY CONTENTS NEIGHBORHOOD The West Loop 06 Fulton Market 08 Map 10 Access 12 NEIGHBORS Offi ces 14 Dining 18 Hospitality 22 Entertainment & Arts 23 Residents 24 Demographics 25 SPACE Overview 26 First Level Retail 28 About McCaffery Interests 29 3 4 5 THE WEST LOOP Once a Marketplace, Always a Marketplace Bounded by Ashland Avenue to the West, the Chicago River to the East, the Eisenhower Expressway to the South and Grand Avenue to the North, the West Loop has played a key role in making Chicago an economic powerhouse. Originally home to the city’s bustling wholesale market district, several of the West Loop’s charismatic warehouses continue to market and distribute food goods today, while neighboring thoroughfares are being revitalized to refl ect and foster the urban life, culture and energy for which this historic area is known. 6 7 FULTON MARKET Dynamic Day & Night Destination At the heart of the West Loop is Fulton Market. The proximity of this quiet, westbound avenue to the city’s nineteenth century rail and stock yards positioned it as a vital hub of Chicago’s growing food enterprises. Wide sidewalks increase walkability and offer opportunities for outdoor dining, parklets and window shopping. Nearby public transportation, bike- sharing stations, and multiple interstate connections makes the area highly accessible by foot, train, bike or car. Just blocks off of Randolph Street’s in-demand “Restaurant Row” and minutes from Chicago’s hip Greektown neighborhood, Fulton Market is at the center of this 24/7 district. ©John8 Joh -

Guam National Wildlife Refuge, Yigo, Guam

28816 Federal Register / Vol. 75, No. 99 / Monday, May 24, 2010 / Notices e.g., permitting electronic submission of Description of the Need for the Participants must submit a new responses. Information and Its Proposed Use: application and updated affordable This notice also lists the following In general, a nonprofit organization housing plan every two years to remain information: must be HUD-approved and meet on the Roster. HUD uses the information Title of Proposal: Application and Re- specific requirements to maintain to ensure that a nonprofit organization certification Packages for Approval of approval and remain on the Nonprofit meets the requirements to participate in Nonprofit Organizations in FHA Organization Roster (Roster). Single Family programs. Activities. This includes an application, OMB Approval Number: 2502–0540. affordable housing plan, annual reports, Frequency of Submission: On Form Numbers: None. and required record keeping. occasion, Annually, Biennially. Number of Annual × Hours per respondents responses response = Burden hours Reporting Burden .............................................................................. 355 0.205 0.147 11,760 Total Estimated Burden Hours: Parties who do not file an appeal in the following methods. You may request 11,760. accordance with the requirements of 43 either a hard copy or CD–ROM. Status: Extension of a currently CFR part 4, subpart E, shall be deemed Agency Web Site: Review or approved collection. to have waived their rights. download a copy of the document at Authority: Section 3507 of the Paperwork ADDRESSES: A copy of the decision may http://www.fws.gov/pacific/planning/. Reduction Act of 1995, 44 U.S.C. 35, as be obtained from: Bureau of Land E-mail: [email protected]. -

Polling Places Nov

City of Chicago PRELIMINARY List of ELECTION DAY Polling Places Nov. 3, 2020 General Election* (All polling place locations are subject to change.) Ward Prec ELECTION DAY Polling Place & Address ("x" indicates that the polling place is not fully accessible.) 1 1 x Yates School 1826 N Francisco Ave 1 2 x Funston School 2010 N Central Park Ave 1 3 x Wells Community Academy 936 N Ashland Ave 1 4 x Commercial Park 1845 W Rice St 1 5 x LaSalle II Magnet School 1148 N Honore St 1 6 x The Ogden Intrnl H S / Chicago 1250 W Erie St 1 7 x Haas Park 2402 N Washtenaw Ave 1 8 x Wicker Park Senior Housing 2020 W Schiller St 1 9 x The Lincoln Lodge 2040 N Milwaukee Ave 1 10 x LaSalle II Magnet School 1148 N Honore St 1 11 Wicker Pk Fieldhouse 1425 N Damen Ave 1 12 Ukranian Village Cultural Ctr 2247 W Chicago Ave 1 13 x Chase School 2021 N Point St 1 14 x De Diego Community Academy 1313 N Claremont Ave 1 15 x De Diego Community Academy 1313 N Claremont Ave 1 16 x Goethe School 2236 N Rockwell St 1 17 x Funston School 2010 N Central Park Ave 1 18 x Create Your Own Space Studio 937 N Western Ave 1 19 x Chase School 2021 N Point St 1 20 x St Sylvester 2915 W Palmer St 1 21 x LaSalle II Magnet School 1148 N Honore St 1 22 x Wright College 1645 N California Ave 1 23 x St Sylvester 2915 W Palmer St 1 24 x Erie Elementary Charter School 1405 N Washtenaw Ave 1 25 x Erie Elementary Charter School 1405 N Washtenaw Ave 1 26 x Funston School 2010 N Central Park Ave 1 27 x The Joinery 2533 W Homer St 1 28 x Windy City Field House 2367 W Logan Bv 1 29 x Bloomingdale -

Designated Historic and Natural Resources Within the I&M Canal

Designated historic and natural resources within the I&M Canal National Heritage Corridor Federal Designations National Cemeteries • Abraham Lincoln National Cemetery National Heritage Areas • Abraham Lincoln National Heritage Area National Historic Landmarks • Adler Planetarium (Chicago, Cook County) • Auditorium Building (Chicago, Cook County) • Carson, Pirie, Scott, and Company Store (Chicago, Cook County) • Chicago Board of Trade Building (LaSalle Street, Chicago, Cook County) • Depriest, Oscar Stanton, House (Chicago, Cook County) • Du Sable, Jean Baptiste Point, Homesite (Chicago, Cook County) • Glessner, John H., House (Chicago, Cook County) • Hegeler-Carus Mansion (LaSalle, LaSalle County) • Hull House (Chicago, Cook County) • Illinois & Michigan Canal Locks and Towpath (Will County) • Leiter II Building (Chicago, Cook County) • Marquette Building (Chicago, Cook County) • Marshall Field Company Store (Chicago, Cook County) • Mazon Creek Fossil Beds (Grundy County) • Old Kaskaskia Village (LaSalle County) • Old Stone Gate, Chicago Union Stockyards (Chicago, Cook County) • Orchestra Hall (Chicago, Cook County) • Pullman Historic District (Chicago, Cook County) • Reliance Building, (Chicago, Cook County) • Rookery Building (Chicago, Cook County) • Shedd Aquarium (Chicago, Cook County) • South Dearborn Street-Printing House Row North (Chicago, Cook County) • S. R. Crown Hall (Chicago, Cook County) • Starved Rock (LaSalle County) • Wells-Barnettm Ida B., House (Chicago, Cook County) • Williams, Daniel Hale, House (Chicago, Cook County) National Register of Historic Places Cook County • Abraham Groesbeck House, 1304 W. Washington Blvd. (Chicago) • Adler Planetarium, 1300 S. Lake Shore Dr., (Chicago) • American Book Company Building, 320-334 E. Cermak Road (Chicago) • A. M. Rothschild & Company Store, 333 S. State St. (Chicago) • Armour Square, Bounded by W 33rd St., W 34th Place, S. Wells Ave. and S. -

Series in PDF Format Here

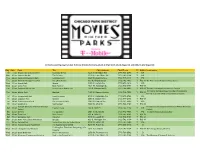

All movie screenings begin at dusk. Estimate 8:30 pm from June-July 15, 8:15 pm from July 16-August 15, and 8:00 pm after August 16. Day Date Park Title Park Address Park Phone CC Rating Underwriter Fri 7-Jun Berger Park Cultural Center Some Like It Hot 6205 N. Sheridan Rd. (773) 761-0376 Y NR Mon 10-Jun Belmont Harbor The 39 Steps 3200 N. Lake Shore Dr. (312) 742-1134 Y NR Tue 11-Jun Donovan Playground Park Goosebumps 2 3620 S.Lituanica Ave. (312) 747-6111 Y PG Tue 11-Jun Ward (A. Montgomery) Park Crazy Rich Asians 630 N. Kingsbury St. (312) 742-7895 Y PG-13 The River North Resident's Association Wed 12-Jun Brands Park Moana 3259 N. Elston Ave. (773) 478-2414 Y PG Wed 12-Jun Union Park Black Panther 1501 W. Randolph St. (312) 746-5494 Y PG-13 Thu 13-Jun Bartelme (Mary) Park Adventures in Babysitting 115 S. Sangamon St. (312) 746-5962 Y PG-13 The Mary Bartelme Park Advisory Council The Wicker Park Bucktown Chamber of Commerce Thu 13-Jun Wicker Park Stardust 1425 N. Damen Avenue (312) 742-7553 Y PG-13 Members and the Wicker Park Advisory Council Fri 14-Jun Eugene Field Park Great Outdoors 5100 N. Ridgeway Ave. (773) 478-9744 Y PG Fri 14-Jun Lindblom Park Creed II 6054 S. Damen Ave. (312) 747-6443 Y PG-13 Fri 14-Jun Pottawattomie Park Ghostbusters (1984) 7340 N. Rogers Ave. (773) 262-5835 Y PG Fri 14-Jun Shedd Park Night School 3660 W. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b 0MB No W24-0018 (Jan. 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing__________________________________________ The Historic Resources of the Chicago Park District B. Associated Historic Contexts The Historical Development of Public Parks in Chicago since 1839 C. Geographical Data The City limits of Chicago/ Illinois I I See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional reqt-jjjjetfienis a& forth in 36^Cr-H"Pact60^ and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. Signature of certifying official Date ___ Director , T1 1 1nnls State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. _________________ Signature of the Keeper of the National Register Date E. Statement of Historic Contexts Discuss each historic context listed in Section B. -

2011 HED Annual Report SCR

CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 3 ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 4 Harper Court 5 Resurrection University 6 Gateway Plaza 7 Green Exchange 8 Accretive Health 9 Hellenic Museum 10 Logan Theater 11 WaterSaver Faucet 12 WMS Gaming 13 CVS Pharmacy 14 TIFWorks 15 Small Business Improvement Fund 15 AFFORDABLE HOUSING 16 North and Talman III 17 Casa Maravilla 18 Independence Apartments 19 Dr. King Legacy Apartments 20 Hope Manor Apartments 21 Zapata Apartments 22 Viceroy Apartments 23 Hairpin Lofts 24 Chicago Low Income Housing Trust Fund 25 PLANNING AND ZONING 26 Metra-Milwaukee District West Line Plan 27 Planned Development Designations 28 Rosehill Nature Preserve 30 Calumet Open Space Reserve 31 Bloomingdale Park and Trail 32 Honore Street Farm 33 Chicago Motor Club 34 Brewery Tied Houses 35 DEPARTMENT AGGREGATES 36 City of Chicago Department of Housing and Economic Development Andrew J. Mooney, Commissioner Michael Jasso, Economic Development Deputy Commissioner Lawrence Grisham, Housing Deputy Commissioner Patti Scudiero, Planning and Zoning Deputy Commissioner Communications and Outreach Division 121 N. LaSalle St. #1000 Chicago, IL 60602 (312) 744-4190 www.cityofchicago.org/hed Spring 2012 Mayor Rahm Emanuel INTRODUCTION The “2011 Project Highlights” booklet is an overview of Department of Housing and Economic Development (HED) projects that were either started or substantially completed during our inaugural year leading Chicago’s planning, housing and economic development functions. Largely coinciding with Mayor Rahm Emanuel’s first year in office, 2011 was charac- terized by new government efficiencies, coordination, and progress. Merged from separate departments, HED’s staff of approximately 225 development professionals worked with unprecedented cooperation to create jobs, expand housing options, and foster quality of life improvements citywide. -

CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOODS Updated by the UIC MS in OT Class of 2022

CHICAGO NEIGHBORHOODS Updated by the UIC MS in OT Class of 2022 HELPFUL WEBSITES TRANSIT: http://www.transitchicago.com/ The Mapquest of Chicago public transit – calculates route options and travel time for anywhere in the city, it’s great! Your UIC unlimited transit pass allows you to ride any city train or bus anytime without having to pay. FYI: school is near the BLUE (Damen Illinois Medical Center stop) and PINK (Polk stop) train lines. AIRPORT FYI: the blue line goes north to O’Hare Airport, and the orange line goes south to Midway Airport. http://ctabustracker.com/ This is an easy reference point for checking bus times. http://bus.uic.edu/ The bus tracker for the UIC busses. www.google.com/transit Google Maps is the most reliable way to figure out public transportation in the city. Has a great app for iPhones as well! (Maps on the iPhone is a little less reliable) GENERAL, AREA BUSINESSES, & SOCIAL EVENTS: http://chicago.metromix.com/ Profile several restaurants, bars, music venues, theaters, street festivals, special events, conventions, etc., including reviews, hours, addresses, phone numbers, and promotions. Can browse by neighborhood, price, genre, date, type of venue, etc. Great way to find the nearest Thai restaurant, bowling alley, sports bar, or movie theater or see what’s happening in the city on a certain date. https://www.timeout.com/chicago/events-calendar Events around the city by month. http://chicago.citysearch.com Profiles area establishments and events. You can also search here for free things to do in Chicago. http://cityofchicago.org Offers some general Chicago information. -

Developed by Contents

DEVELOPED BY CONTENTS NEIGHBORHOOD The West Loop 06 Fulton Market 08 Map 10 Access 12 NEIGHBORS Offi ces 14 Dining 18 Hospitality 22 Entertainment & Arts 23 Residents 24 Demographics 25 SPACE Overview 26 First Level Retail 28 About McCaffery Interests 29 3 4 5 THE WEST LOOP Once a Marketplace, Always a Marketplace Bounded by Ashland Avenue to the West, the Chicago River to the East, the Eisenhower Expressway to the South and Grand Avenue to the North, the West Loop has played a key role in making Chicago an economic powerhouse. Originally home to the city’s bustling wholesale market district, several of the West Loop’s charismatic warehouses continue to market and distribute food goods today, while neighboring thoroughfares are being revitalized to refl ect and foster the urban life, culture and energy for which this historic area is known. 6 7 FULTON MARKET Dynamic Day & Night Destination At the heart of the West Loop is Fulton Market. The proximity of this quiet, westbound avenue to the city’s nineteenth century rail and stock yards positioned it as a vital hub of Chicago’s growing food enterprises. Wide sidewalks increase walkability and offer opportunities for outdoor dining, parklets and window shopping. Nearby public transportation, bike- sharing stations, and multiple interstate connections makes the area highly accessible by foot, train, bike or car. Just blocks off of Randolph Street’s in-demand “Restaurant Row” and minutes from Chicago’s hip Greektown neighborhood, Fulton Market is at the center of this 24/7 district. ©John8 Joh -

Neighborhood Plan West Loop

West Loop Neighborhood Plan Prepared by: Neighbors of West Loop Chicago, IL August, 2018 West Loop Neighborhood Plan In 2013, an effort was initiated to increase collaboration among residents across the four wards of the transforming West Loop. The Fulton River District Association (FRDA), a neighborhood group located in the northeast portion of the West Loop, looked beyond its boundaries to engage nearby volunteers. FRDA worked with residents that were participating in other community organizations like park advisory councils (PACs), Community Alternative Policing Strategy (CAPS), local school councils, and other positive community organizations. In January of 2014, the Fulton River District Association became Neighbors of West Loop and expanded its geographic reach to include all of the West Loop as we know it today. Neighbors of West Loop (NoWL) is a neighborhood organization comprised of West Loop residents who bring together others in the area who want to make a positive impact on our vibrant community. We are a non-profit organization, supported by our membership and other West Loop residents who volunteer their time to benefit the organization. The organization is founded on transparency and welcomes anyone who wants to make a difference at the local level. The positions that we establish and the initiatives that we promote are aligned with the feedback that we receive from the community. Our goal is to empower residents who wish to volunteer their time for the West Loop. We believe in transparency and the idea that every resident should have the opportunity to be informed and to be heard on issues that affect their community.