The Evolution of Israel's Anti-Defection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Outline Plan NOP 37/H for Natural Gas Treatment Facilities

Lerman Architects and Town Planners, Ltd. 120 Yigal Alon Street, Tel Aviv 67443 Phone: 972-3-695-9093 Fax: 9792-3-696-0299 Ministry of Energy and Water Resources National Outline Plan NOP 37/H For Natural Gas Treatment Facilities Environmental Impact Survey Chapters 3 – 5 – Marine Environment June 2013 Ethos – Architecture, Planning and Environment Ltd. 5 Habanai St., Hod Hasharon 45319, Israel [email protected] Unofficial Translation __________________________________________________________________________________________________ National Outline Plan NOP 37/H – Marine Environment Impact Survey Chapters 3 – 5 1 Summary The National Outline Plan for Natural Gas Treatment Facilities – NOP 37/H – is a detailed national outline plan for planning facilities for treating natural gas from discoveries and transferring it to the transmission system. The plan relates to existing and future discoveries. In accordance with the preparation guidelines, the plan is enabling and flexible, including the possibility of using a variety of natural gas treatment methods, combining a range of mixes for offshore and onshore treatment, in view of the fact that the plan is being promoted as an outline plan to accommodate all future offshore gas discoveries, such that they will be able to supply gas to the transmission system. This policy has been promoted and adopted by the National Board, and is expressed in its decisions. The final decision with regard to the method of developing and treating the gas will be based on the developers' development approach, and in accordance with the decision of the governing institutions by means of the Gas Authority. In the framework of this policy, and in accordance with the decisions of the National Board, the survey relates to a number of sites that differ in character and nature, divided into three parts: 1. -

Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship

INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND ADVICE FOR THE PARLIAMENT INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES Research Paper No. 4 2002–03 Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship DEPARTMENT OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY ISSN 1328-7478 Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2003 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members of the public. Published by the Department of the Parliamentary Library, 2003 I NFORMATION AND R ESEARCH S ERVICES Research Paper No. 4 2002–03 Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship Sarah Miskin Politics and Public Administration Group 24 March 2003 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Martin Lumb and Janet Wilson for their help with the research into party defections in Australia and Cathy Madden, Scott Bennett, David Farrell and Ben Miskin for reading and commenting on early drafts. -

("DSCC") Files This Complaint Seeking an Immediate Investigation by the 7

COMPLAINT BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION CBHMISSIOAl INTRODUCTXON - 1 The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee ("DSCC") 7-_. J _j. c files this complaint seeking an immediate investigation by the 7 c; a > Federal Election Commission into the illegal spending A* practices of the National Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee (WRSCIt). As the public record shows, and an investigation will confirm, the NRSC and a series of ostensibly nonprofit, nonpartisan groups have undertaken a significant and sustained effort to funnel "soft money101 into federal elections in violation of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended or "the Act"), 2 U.S.C. 5s 431 et seq., and the Federal Election Commission (peFECt)Regulations, 11 C.F.R. 85 100.1 & sea. 'The term "aoft money" as ueed in this Complaint means funds,that would not be lawful for use in connection with any federal election (e.g., corporate or labor organization treasury funds, contributions in excess of the relevant contribution limit for federal elections). THE FACTS IN TBIS CABE On November 24, 1992, the state of Georgia held a unique runoff election for the office of United States Senator. Georgia law provided for a runoff if no candidate in the regularly scheduled November 3 general election received in excess of 50 percent of the vote. The 1992 runoff in Georg a was a hotly contested race between the Democratic incumbent Wyche Fowler, and his Republican opponent, Paul Coverdell. The Republicans presented this election as a %ust-win81 election. Exhibit 1. The Republicans were so intent on victory that Senator Dole announced he was willing to give up his seat on the Senate Agriculture Committee for Coverdell, if necessary. -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

Download File

Columbia University Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Human Rights Studies Master of Arts Program Silencing “Breaking the Silence”: The Israeli government’s agenda respecting human rights NGOs activism since 2009 Ido Dembin Thesis Adviser: Prof. Yinon Cohen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 12 September, 2018 Abstract This research examines a key aspect in the deterioration of Israeli democracy between 2009-2018. Mainly, it looks at Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's Right-wing governments utilization of legislative procedure to limit the right to free speech. The aspects of the right to free speech discussed here pertain to dissenting and critical activism against these government’s policies. The suppression of said right is manifested in the marginalization, delegitimization and ultimately silencing of its expression in Human Rights NGOs activism. To demonstrate this, the research presents a case study of one such NGO – “Breaking the Silence” – and the legal and political actions designed to cause its eventual ousting from mainstream Israeli discourse. The research focuses on the importance and uniqueness of this NGO, as well as the ways in which the government perceives and acts against it. First, it analyzes the NGO’s history, modus operandi and goals, emphasizing the uniqueness that makes it a particularly fascinating case. Then, it researches the government’s specific interest in crippling and limiting its influence. Finally, it highlights the government’s toolbox and utilization thereof against it. By shining a light on this case, the research seeks to show the process of watering down of a fundamental right within Israeli democracy – which is instrumental to understanding the state’s risk of decline towards illiberal democracy. -

The Decline of Collective Responsibility in American Politics

MORRIS P. FIORINA The Decline of Collective Responsibility inAmerican Politics the founding fathers a Though believed in the necessity of establishing gen to one uinely national government, they took great pains design that could not to lightly do things its citizens; what government might do for its citizens was to be limited to the functions of what we know now as the "watchman state." Thus the Founders composed the constitutional litany familiar to every schoolchild: a they created federal system, they distributed and blended powers within and across the federal levels, and they encouraged the occupants of the various posi tions to check and balance each other by structuring incentives so that one of to ficeholder's ambitions would be likely conflict with others'. The resulting system of institutional arrangements predictably hampers efforts to undertake initiatives and favors maintenance of the status major quo. Given the historical record faced by the Founders, their emphasis on con we a straining government is understandable. But face later historical record, one two that shows hundred years of increasing demands for government to act positively. Moreover, developments unforeseen by the Founders increasingly raise the likelihood that the uncoordinated actions of individuals and groups will inflict serious on the nation as a whole. The of the damage by-products industri not on on al and technological revolutions impose physical risks only us, but future as well. Resource and international cartels raise the generations shortages spectre of economic ruin. And the simple proliferation of special interests with their intense, particularistic demands threatens to render us politically in capable of taking actions that might either advance the state of society or pre vent foreseeable deteriorations in that state. -

A Pre-Feasibility Study on Water Conveyance Routes to the Dead

A PRE-FEASIBILITY STUDY ON WATER CONVEYANCE ROUTES TO THE DEAD SEA Published by Arava Institute for Environmental Studies, Kibbutz Ketura, D.N Hevel Eilot 88840, ISRAEL. Copyright by Willner Bros. Ltd. 2013. All rights reserved. Funded by: Willner Bros Ltd. Publisher: Arava Institute for Environmental Studies Research Team: Samuel E. Willner, Dr. Clive Lipchin, Shira Kronich, Tal Amiel, Nathan Hartshorne and Shae Selix www.arava.org TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 HISTORICAL REVIEW 5 2.1 THE EVOLUTION OF THE MED-DEAD SEA CONVEYANCE PROJECT ................................................................... 7 2.2 THE HISTORY OF THE CONVEYANCE SINCE ISRAELI INDEPENDENCE .................................................................. 9 2.3 UNITED NATIONS INTERVENTION ......................................................................................................... 12 2.4 MULTILATERAL COOPERATION ............................................................................................................ 12 3 MED-DEAD PROJECT BENEFITS 14 3.1 WATER MANAGEMENT IN ISRAEL, JORDAN AND THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY ............................................... 14 3.2 POWER GENERATION IN ISRAEL ........................................................................................................... 18 3.3 ENERGY SECTOR IN THE PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY .................................................................................... 20 3.4 POWER GENERATION IN JORDAN ........................................................................................................ -

Institute for the Study of Modern Israel ~ISMI~

Institute for the Study of Modern Israel ~ISMI~ November 10 – 11, 2018 Atlanta, Georgia ISMI.EMORY.EDU 1 2 Welcome to the 20th Anniversary Celebration of the Emory Institute for the Study of Modern Israel (ISMI). SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 10, 2018 1:30pm-1:45pm Opening Remarks (Ken Stein) 1:45pm-2:45pm Israel: 1948-2018 A Look Back to the Future (Asher Susser, Yitzhak Reiter, Yaron Ayalon, Rachel Fish, Ken Stein-moderator) 2:45pm-3:00pm Break 3:00pm-4:15pm Israel and its Neighborhood (Alan Makovsky, Jonathan Schanzer, Joel Singer, Asher Susser-moderator) 4:15pm-5:30pm US Foreign Policy toward Israel (Todd Stein, Alan Makovsky, Jonathan Schanzer, Ken Stein-moderator) 5:30pm-6:00pm Break 6:00pm-6:45pm Wine Reception 6:45pm-7:45pm ISMI at Emory: Impact on Emory College, Atlanta and Beyond (Introductory Remarks by Ambassador Judith Varnai Shorer, Consul General of Israel to the Southeastern United States, Michael Elliott, Dov Wilker, Lois Frank, Joshua Newton, Jay Schaefer, Ken Stein-moderator) 7:45pm-8:45pm Dinner 9:00pm-10:00pm Musical Performance by Aveva Dese with Introduction by Eli Sperling 10:30pm-midnight AFTER HOURS Reading Sources and Shaping Narratives: 1978 Camp David Accords (Ken Stein) SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 11, 2018 7:00am-8:30am Breakfast 8:30am-9:30am Israel and the American Jewish Community (Allison Goodman, Jonathan Schanzer, Alan Makovsky, Ken Stein-moderator) 9:30am-10:30am Reflections of Israel Learning at Emory (Dana Pearl, Jay Schaefer, Mitchell Tanzman, Yaron Ayalon, Yitzhak Reiter, Ken Stein-moderator) 10:30am-10:45am Break 10:45am-11:30am Foundations, Donors, and Israel Studies (Stacey Popovsky, Rachel Fish, Dan Gordon, Ken Stein-moderator) 11:30am-12:30pm One-state, two states, something else? (Rachel Fish, Yitzhak Reiter, Joel Singer, Jonathan Schanzer, Ken Stein-moderator) 12:30pm-12:45pm Closing Remarks - ISMI’s Future and What’s Next 12:45pm Box Lunch 3 Full Agenda - Saturday November 10, Saturday – 1:30pm-1:45pm Opening Remarks Welcoming thoughts about our two days of learning. -

Partisanship in Perspective

Partisanship in Perspective Pietro S. Nivola ommentators and politicians from both ends of the C spectrum frequently lament the state of American party politics. Our elected leaders are said to have grown exceptionally polarized — a change that, the critics argue, has led to a dysfunctional government. Last June, for example, House Republican leader John Boehner decried what he called the Obama administration’s “harsh” and “hyper-partisan” rhetoric. In Boehner’s view, the president’s hostility toward Republicans is a smokescreen to obscure Obama’s policy failures, and “diminishes the office of the president.” Meanwhile, President Obama himself has complained that Washington is a city in the grip of partisan passions, and so is failing to do the work the American people expect. “I don’t think they want more gridlock,” Obama told Republican members of Congress last year. “I don’t think they want more partisanship; I don’t think they want more obstruc- tion.” In his 2006 book, The Audacity of Hope, Obama yearned for what he called a “time before the fall, a golden age in Washington when, regardless of which party was in power, civility reigned and government worked.” The case against partisan polarization generally consists of three elements. First, there is the claim that polarization has intensified sig- nificantly over the past 30 years. Second, there is the argument that this heightened partisanship imperils sound and durable public policy, perhaps even the very health of the polity. And third, there is the impres- sion that polarized parties are somehow fundamentally alien to our form of government, and that partisans’ behavior would have surprised, even shocked, the founding fathers. -

Party System in South and Southeast Asia

PARTY SYSTEM IN SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIA A THEMATIC REPORT BASED ON DATA 1900-2012 Authors: Julio Teehankee, Medet Tiulegenov, Yi-ting Wang, Vlad Ciobanu, and Staffan I. Lindberg V-Dem Thematic Report Series, No. 2, October 2013. Prepared for The European Union, represented by the European Commission under Service Contract No. EIDHR 2012/298/903 2 About V-Dem Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) is a new approach to conceptualization and measurement of democracy. It is a collaboration between some 50+ scholars across the world hosted by the Department of Political Science at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden; and the Kellogg Institute at the University of Notre Dame, USA. With four Principal Investigators (PIs), three Project Coordinators (PCs), fifteen Project Managers (PMs) with special responsibility for issue areas, more than thirty Regional Managers (RMs), almost 200 Country Coordinators (CCs), a set of Research Assistants (RAs), and approximately 3,000 Country Experts (CEs), the V-Dem project is one of the largest ever social science research-oriented data collection programs. V-Dem is collecting data on 329 indicators of various aspects democracy tied to the core of electoral democracy as well as six varying properties: liberal, majoritarian, consensual, participatory, deliberative and egalitarian dimensions of democracy. A pilot study in 2011 tested the preliminary set of indicators and the data collection interfaces and procedures. Twelve countries from six regions of the world were covered, generating 462,000 data points. In the main phase, all countries of the world will be covered from 1900 to the present, generating some 22 million data across the 329 indicators, as well as several indices of varying forms of democracy. -

Spring 2009, Emory University Dr. Doron Shultziner ( [email protected] )

Contemporary Issues in Israeli Politics and Society (HIST 489SWR/POLS 490SWR) Spring 2009, Emory University Dr. Doron Shultziner ( [email protected] ) This colloquium looks at developments in Israeli politics, society and constitutional arrangements from the 1990s until present day. We will explore contemporary issues in view of their historical evolution. New political players, and societal and political phenomena in Israel will be discussed as well. Examination and Grading : Students will write two short papers (1500 words) during the semester, each constitutes 20% of the final grade. First short paper is due in early March and the second paper is due in early April. A final paper (about 20 pages) will constitute 60% of the final grade. The final paper is due May 5, 2009. Active class participation is necessary and may count up to an additional 10% bonus to the final grade. Students will send weekly reflection paragraphs about the readings and lead discussions on chosen topics. Students are also required to meet with the course assistant Dr. Chris Palazzolo for their final paper. The syllabus is subject to change based on class dynamics and availability of guest speakers. Students are strongly advised to follow current events on the Israeli daily Haaretz: www.haaretz.com Contact details: Dr. Doron Shultziner Office phone: 404-727-9698 Office: Bowden Hall 102 Office hours Mondays 12:50-13:50 [email protected] Dr. Chris Palazzolo , Course Research Assistant and Social Sciences Librarian Office 404-727-0143 [email protected] (also available via Learnlink) 1. Introduction and Historical Background (1.26.09) Mahler, Gregory S. -

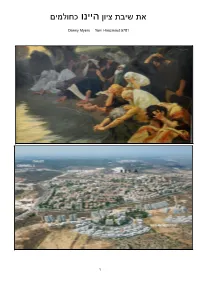

Final Version היינו כחולמים תשפ"א

את שיבת ציון היינו כחולמים Danny Myers Yom Haazmaut 5781 1 Israel-The heart, soul & spirit of the Jew 1. Introduction-The Rav on Israel (1958) Dr. Arnold Lustiger The prayer recited after having partaken of a meal of bread, Birkat Hamazon, is an intricate series of four blessings. In Birkat Hamazon, we thank God for the food, for the land, and for the future rebuilding of Jerusalem, and we conclude with a blessing of gratitude. In the prayer for the land, mention is made of God's covenant of circumcision and the giving of the Torah. A unique aspect of the recitation of Birkat Hamazon is the obligation of Zimun, in which a designated leader introduces responsive statements of blessing to others who have eaten with him. The wording of the responsive statements varies depending on whether the number of participants is three or ten; the Mishnah in Berakhot goes further, detailing a series of variant wordings for one hundred, one thousand, or ten thousand participants, respectively. In contrast, after eating grapes, pomegranates, or figs, the fruits for which the Land of Israel is praised, only one much shorter blessing, the Berakhah Me'ein Shalosh, is recited. Although the themes of land and Jerusalem are also contained in the Berakhah Me'ein Shalosh, they appear in greatly abbreviated form. Allusions to circumcision and the giving of the Torah are entirely absent. The obligation for Zimun, the synchronicity associated with Birkat Hamazon, is also absent in the Berakhah Me'ein Shalosh. a. Ezrah-Man's Partnership with God The halakhic reason for the difference between the blessings recited after the consumption of a meal consisting of bread on one hand and fruit on the other is clearly laid out in the Talmud.