Indra in the Epics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iconography of the Recently Discovered Naga Sculptures from Pamba River Basin, Pathanamthitta District, South Kerala

Iconography of the Recently Discovered Naga Sculptures from Pamba River Basin, Pathanamthitta District, South Kerala Ambily C.S.1, Ajit Kumar2 and Vinod Pancharath3 1. Excavation Branch II, Archaeological survey of India, Purana Qila, New Delhi – 110001, India (Email: [email protected]) 2. Department of Archaeology, University of Kerala, Kariavattom Campus, Thiruvananthapuram - 695581, Kerala, India (Email: [email protected]) 3. Industrial Design Centre, Indian Institute of Technology, Powai, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India (Email: [email protected]) Received: 25 September 2015; Accepted: 18 October 2015; Revised: 09 November 2015 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 3 (2015): 618-634 Abstract: Recent exploration by the first author brought to light interesting Naga sculptures from the middle ranges of Pamba River basin. All the sculptures are made out of granite and can be classified into Nagarajas and Nagayakshis except one which is a female naga devotee. This paper tries to briefly discuss the iconography, chronology and significance of the sculptures. Keywords: Exploration, Pamba River Basin, Kerala, Nagarajas, Nagayakshis, Iconography, Chronology Introduction Pamba is one of the important and third longest rivers in Kerala. It is apparently the river Baris/Bans mentioned in records of Pliny (Menon 1967-62). It originates from Pulachimalai hill in Peermade plateau at an altitude of 1650 MSL and has a length of 176km. It flows through Idukki, Pathanamthitta and Alappuzha districts and finally empties into the Vembanadu Lake. During medieval period Pamba basin harbored prosperous settlement like Kaviyur, Thiruvanmandoor, Perunnayil and Thiruvalla. Naga and yakshi images have earlier been reported from Niranam-Tiruvalla area (Mathew 2006). The present discoveries add to the list of known images. -

Researches on Poison, Garuda-Birds and Naga-Serpents Based on the Sgrub Thabs Kun Btus

Researches on Poison, Garuda-birds and Naga-serpents based on the Sgrub thabs kun btus ALEX WAYMAN Tibetan literature deals with poison in a number of texts, conveniently in corporated in the Tibetan sadhana (deity evocation) collection Sgrub thabs kun btus,1 especially in Vols. Cha and Nya of the fourteen-volume set. Here the term for 'poison' (T. dug) has a range of usages and applications far ex ceeding what we could expect in Western conceptions, also far exceeding those found in Indian Buddhism itself. To differentiate the part due to the In dian heritage from what else is found in these Tibetan texts, whatever be the source, it is relevant to introduce numerical groups, namely, the three, the four, and the five kinds of poison. The threefold system does not implicate the Garuda-birds or Naga-serpents. The system of four poisons, with a fifth one added, in terms of the four or five elements, goes with both the Garuda-birds and Naga-serpents; and a secondary system of five poisons was found in a iion-faced' DakinT text. The threefold set of poison In an early, primitive paper I dealt with the Buddhist theory of poison, which stresses three psychological poisons—lust, hatred, and delusion (in Sanskrit, usually rdga, dvesa, moha).2 The Indian books on medicine, includ ing Vagbhata's Astahgahrdayasamhita, which was translated into Tibetan along with a large commentary, set forth two kinds of natural poisons: 'stable' poison from the stationary realm, e.g. from roots of plants; and 'mobile' poi son from the moving realm, e.g. -

17-Chapter-16-Versewise.Pdf

BHAGAVAD GITA Chapter 16 Daivasura-Sampad-Vibhaga Yoga (The Divine and Demoniac Natures Defined) 1 Chapter 16 Introduction : 1) Of vain hopes, of vain actions, of vain knowledge and senseless (devoid of discrimination), they verily are possessed of the delusive nature of raksasas and asuras. [Chapter 9 – Verse 12] Asura / Raksasa Sampad : • Moghasah, Mogha Karmanah – false hopes from improper actions. Vicetasah : • Lack of discrimination. • Binds you to samsara. 2) But the Mahatmas (great souls), O Partha, partaking of My divine nature, worship Me with a single mind (with a mind devoted to nothing else), knowing Me as the imperishable source of all beings. [Chapter 9 – Verse 13] Daivi Sampad : • Seek Bagawan. • Helps to gain freedom from Samsara. 2 • What values of the mind constitute spiritual disposition and demonic disposition? Asura – Sampad Daivi Sampad - Finds enjoyment only in - Make choice as per value sense objects. structure, not as per - Will compromise to gain convenience. the end. • Fields of experiences - Kshetram change but the subject Kshetrajna, knower is one in all fields. • Field is under influence of different temperaments – gunas and hence experiences vary from individual to individual. • Infinite is nature of the subject, transcendental state of perfection and pure knowledge (Purushottama). • This chapter describes how the knower pulsates through disciplined or undisciplined field of experience. • Field is the 3 gunas operative in the minds of individuals. • Veda is a pramana only for prepared mind. Values are necessary to gain knowledge – chapter 13, 14, 15 are direct means to liberation through Jnana yoga. Chapter 16, 17 are values to gain knowledge. 3 Chapter 16 - Summary Verse 1 - 3 Verse 4 - 21 Verse 22 Daivi Sampat (Spiritual) – 18 Values Asuri Sampat (Materialistic) – 18 Values - Avoid 3 traits and adopt daivi sampat and get qualifications 1. -

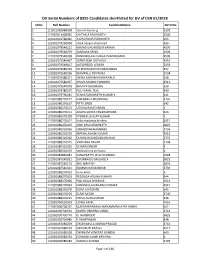

DV Sl No.S of 8255 Cen 01 2018.Xlsx

DV Serial Numbers of 8255 Candidates shortlisted for DV of CEN 01/2018 Sl No. Roll Number CandidateName DV Sl No. 1 111021092980008 ramesh kumar g 2592 2 121001013400035 CHITYALA RAVIKANTH 4506 3 121001022780082 JUJJAVARAPU SRIMANTH 635 4 121001079230008 shaik naseer ahammad 636 5 121001079540221 KAMADI JAGADEESH VARMA 4507 6 121001079540279 SANDAKA SRINU 4508 7 121001079540338 KANDREGULA DURGA PHANIKUMAR 4509 8 121001079540407 VENKATESH GUTHULA 4510 9 121001079540817 KATIKIREDDI LOKESH 2593 10 121001079580229 DILEEPKUMAR DEVARAKONDA 637 11 121001079580296 MAMPALLI PRIYANKA 3734 12 121001079580321 CHINA AKKAIAH KANKANALA 638 13 121001079580337 NAGALAKSHMI PONNURI 4511 14 121001079640078 BHUKYA DASARADH 639 15 121001079780207 PULI VIMAL TEJA 640 16 121001079790242 VENKATABHARATH KUMAR Y 641 17 121001080270122 KALLAPALLI ARUNBABU 3735 18 121001080270167 PITTA BABJI 642 19 121001080270174 UDDISA RAMCHARAN 1 20 121001080270211 ADAPA SURYA CHAKRADHARA 643 21 121001080270328 PYDIMALLA AJAY KUMAR 2 22 121001080270412 Kalla chaitanya krishna 4512 23 121001080270493 JAMI KASI VISWANATH 6822 24 121001080310065 DARABOINA RAMBABU 3736 25 121001080310176 SEPENA ASHOK KUMAR 4513 26 121001080310262 DUNNA HEMASUNDARA RAO 3737 27 121001080310275 VANDANA PAVAN 3738 28 121001080310395 DUNNA DINESH 3 29 121001080310479 vattikuti siva srinivasu 4 30 121001083840041 KANAPARTHI JAYA CHANDRA 2594 31 121001087540021 SIVUNNAIDU MUDADLA 6823 32 121001087540116 ARJI MAHESH 6824 33 121001087540321 KOMMA RAVISANKAR 3739 34 121001088270010 kona kiran 5 35 121001088270019 -

Aranyakhanda Quiz – 2016 Questions Without Answers ( Please Find The

Aranyakhanda quiz – 2016 Questions without answers ( Please find the answers yourself) 1. Who wrote the Ramayana? 2. How many khandas are there in the Ramayana? Name them in order. 3. How many sargas are there in the Aranyakhanda? 4. Which forest did Rama enter in the beginning of Aranyakhanda? 5. Who is the Lord of the birds? 6. Name the Lord of wind. 7. Name the God of death. 8. Who cursed Viradha to be a rakshasa? 9. Who killed Viradha? 10. Who gave immortal life to Sarabhanga? 11. How many years passed happily with Rama, Lakshmana and Sita living in the forest with the sages? 12. Name the two rakshasas that Agastya killed. 13. For whom was the viswakarman bow made? 14. Whose was the exhaustless pair of quivers? 15. What weapon did Agastya give rama? 16. Name vasishta’s wife. 17. To which place did Agastya direct Rama to? 18. On the banks of which river is the place that Agastya directed Rama to? 19. How many daughters did Daksha have? 20. How many of Daksha’s daughters did Kashyapa marry? 21. Name adisesha’s mother. 22. ___ is the mother of Daityas. Diti. 23. From where did Bharata rule? 24. On the banks of which river is the place that Bharata ruled from? 25. Who is the Asura of the eclipse? 26. Name Ravana’s sister. 27. Name Janaka’s kingdom. 28. Name Ravana’s father. 29. When Lakshmana disgraced Surpanakha, to whom did she go in grievance? 30. Where did Khara live? 31. Name the three types of Gunas. -

Hanuman Chalisa.Pdf

Shree Hanuman Chaleesa a sacred thread adorns your shoulder. Gate of Sweet Nectar 6. Shankara suwana Kesaree nandana, Teja prataapa mahaa jaga bandana Shree Guru charana saroja raja nija You are an incarnation of Shiva and manu mukuru sudhari Kesari's son/ Taking the dust of my Guru's lotus feet to Your glory is revered throughout the world. polish the mirror of my heart 7. Bidyaawaana gunee ati chaatura, Baranaun Raghubara bimala jasu jo Raama kaaja karibe ko aatura daayaku phala chaari You are the wisest of the wise, virtuous and I sing the pure fame of the best of Raghus, very clever/ which bestows the four fruits of life. ever eager to do Ram's work Buddhi heena tanu jaanike sumiraun 8. Prabhu charitra sunibe ko rasiyaa, pawana kumaara Raama Lakhana Seetaa mana basiyaa I don’t know anything, so I remember you, You delight in hearing of the Lord's deeds/ Son of the Wind Ram, Lakshman and Sita dwell in your heart. Bala budhi vidyaa dehu mohin harahu kalesa bikaara 9. Sookshma roopa dhari Siyahin Grant me strength, intelligence and dikhaawaa, wisdom and remove my impurities and Bikata roopa dhari Lankaa jaraawaa sorrows Assuming a tiny form you appeared to Sita/ in an awesome form you burned Lanka. 1. Jaya Hanumaan gyaana guna saagara, Jaya Kapeesha tihun loka ujaagara 10. Bheema roopa dhari asura sanghaare, Hail Hanuman, ocean of wisdom/ Raamachandra ke kaaja sanvaare Hail Monkey Lord! You light up the three Taking a dreadful form you slaughtered worlds. the demons/ completing Lord Ram's work. -

And Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Raven and the Serpent: "The Great All- Pervading R#hula" Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet Cameron Bailey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE RAVEN AND THE SERPENT: “THE GREAT ALL-PERVADING RHULA” AND DMONIC BUDDHISM IN INDIA AND TIBET By CAMERON BAILEY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Religion Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Cameron Bailey defended this thesis on April 2, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bryan Cuevas Professor Directing Thesis Jimmy Yu Committee Member Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my adviser Dr. Bryan Cuevas who has guided me through the process of writing this thesis, and introduced me to most of the sources used in it. My growth as a scholar is almost entirely due to his influence. I would also like to thank Dr. Jimmy Yu, Dr. Kathleen Erndl, and Dr. Joseph Hellweg. If there is anything worthwhile in this work, it is undoubtedly due to their instruction. I also wish to thank my former undergraduate advisor at Indiana University, Dr. Richard Nance, who inspired me to become a scholar of Buddhism. -

Janamejaya I Janamejaya I

JANAMEJAYA I 346 JANAMEJAYA I King mistaking the sage's silence for haughtiness threw Yajna gala. Janamejaya received the young Sage with in anger a dead snake round his neck and went away. all respect and promised to grant his desire what- But, within seven days of the incident Pariksit was ever that be. Astlka's demand was that the Sarpa Satra bitten to death by Taksaka, king of the Nagas accord- should be stopped. Though Janamejaya was not for ing to the curse pronounced on him by Gavijata, stopping the yajna, he was reminded of his promise to son of sage Samika. grant any desire of Astlka and the latter insisted on the Janamejaya was only an infant at the time of his stopping of the Satra. Janamejaya stopped it. Astlka father's death. So the obsequies of the late king were blessed that the serpents which had died at the Satra his ministers. After that at an attain salvation. performed by auspicious would (Adi Parva, Chapters 52-58 ; time Janamejaya was crowned King. Within a short Devi Bhagavata, 2nd Skandha) . time he mastered statecraft. Dhanurvidya was taught 6) Listens to the Bhdrata story. While the Sarpa Satra by Krpacarya. Very soon he earned reputation as an was being conducted Vyasa came over there and related efficient administrator. He got married in due course. the whole story of the Mahabharata at the request of (Devi Bhagavata, 2nd Skandha) . Janamejaya. (Adi Parva, Chapter 60) . 4) His hatred towards snakes. In the course of a talk 7) Saramd's curse. Janamejaya along with his brother one day with Janamejaya Uttanka the sage detailed to once performed a yajna of long duration at Kuruksetra. -

Bhagavad Gita Chapter 10: Divine Emanations

Bhagavad Gita Chapter 10: Divine Emanations Tonight we will be doing chapter 10 of the Bhagavad Gita, Vibhuti Yoga, The Yoga of Divine Emanations. But first I want to talk about the nature of the journey. For most of us Westerners this aspect of the Gita is not available to us. Very few people in the West open up to God, to the collective consciousness, in the experiential way that is being revealed here. Most spiritual teachings have more to do with the development of the psychic intelligence and its relationship to truth. Vibhuti Yoga is truly devotional. A vast majority of people have a devotional relationship or feeling for whatever God or Allah or Zoroaster represents. It comes from something in our human nature that is transferring onto an idea, from the human collective consciousness, and is different from what we will be talking about today. (2:00) Vibhuti Yoga is a direct revelation from the universe to the individual. What we might call devotion is absolutely felt, but of a completely different order than what we would call religious devotion or the fervor that occurs with born again Christians or with people that are motivated from their vital for this passionate relationship, for this idea of God. That comes from the higher heart, the higher vital, the part of our human nature that is rising up from our focus on our relationships and attachments and identifications associated with community and society. It is a part of us that lifts to a possibility. It is to some extent associated with what I call the psychic heart. -

Payyannur Pattu

PAURIKA 587 PAYYANNUR PATTU PAURIKA. A king of the ancient country Purikanagari. will get the benefit of worshipping Visnu for a year. is to be in the He was such a sinner that he was reborn as a jackal This worship conducted months of in his next birth. Asadha Sravana (Chapter 111, Sand Parva) . (July), (August) Prausthapada PAUR^AMASA. SonofMarlci. His mother was called (September), As vina (October) and Karttika (Novem- Sambhuti. Paurnamasa had two sons named Virajas ber) A sacred Pavitra (sacred thread or ring of Kusa is either in and Parvata. (Chapter 10, Ariisa 1, Visnu Purana). grass) to be prepared gold, silver, copper, PAUSAJ1T. One of the sages belonging to the tradition cotton or silk. A specially purified cotton thread is of the of under also The Pavitra is to be made of three threads disciples Vyasa. (See Guruparampara) . enough woven The Pavitra is to be made PAUSAMASA. The month of Pausa (January) . During together. holy by 108 times the mantra or even half this month, on the full moon day the constellation reciting Gayatri of that number is 108 times or more Pusya and the moon join in a zodiac. He who takes enough. Reciting is considered tobeUttama half of it is considered food only once a day during this month will get beauty, (best) ; and less than it is considered fame and prosperity. (Chapter 106, Anusasana Parva). Madhyama (tolerable) adhama The Pavitra should then be tied PAUSPINJI. A sage belonging to the tradition of (worst). to mandalas and the mantra to be recited at the time disciples of Vyasa. -

The Plurality of Draupadi, Sita and Ahalya

Many Stories, Many Lessons: The Plurality of Draupadi, Sita and Ahalya Benu Verma Assistant Professor, USHSS Guru Gobind Singh Indraprastha University Dwarka, Delhi Abstract: The relationship between life and literature is a dialogic one. Life inspires literature and literature in turn influences life. Various genres in which literature is manifested reflect on the orientation, significance as well as the place of the text in its social environment. Mikhail Bakhtin proposes that genres dictate the reception of a text. Yet the same text could be interpreted differently in different times and contexts and be rewritten to reflect the aspirations of the author and her/his times. The many life stories of the feminine figures from the epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata assert not only the inconclusive nature of myth and the potency of these epics, they also tell us that with changing political and social milieu the authors reinterpret and record anew given stories to contribute to the literature of their times. Draupadi as the epic heroine of Mahabharata has been written about popularly and widely and in each version with a new take on the major milestones of her life like her five husbands and her birth from fire. The motifs of her disrobing and her hair have been employed variedly to tell various stories, sometimes of oppression and at others of liberation, each belonging to a different time and space. Each story reflected the political stance and aspiration of its author and read by readers differently as per their times and contexts. Through an examination of various literary renditions of the feminine figures from the epics, like Draupadi, Sita, and Ahalya, this paper discusses the relationship between life and literature and how changing times call for changing forms of literature. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh.