Body Piercing Complications and Prevention of Health Risks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

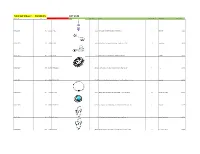

Total Lot Value = $5,520.15 LOT #149 Location Id Lot # Item Id Sku Image Store Price Model Store Quantity Classification Total Value

Total Lot Value = $5,520.15 LOT #149 location_id Lot # item_id sku Image store_price model store_quantity classification Total Value A10-S11-D009 149 143692 BR-2072 $11.99 Pink CZ Sparkling Heart Dangle Belly Button Ring 1 Belly Ring $11.99 A10-S11-D010 149 67496 BB-1011 $4.95 Abstract Palm Tree Surgical Steel Tongue Ring Barbell - 14G 10 Tongue Ring $49.50 A10-S11-D013 149 113117 CA-1346 $11.95 Triple Bezel CZ 925 Sterling Silver Cartilage Earring Stud 6 Cartilage $71.70 A10-S11-D017 149 150789 IX-FR1313-10 $17.95 Black-Plated Stainless Steel Interlocked Pattern Ring - Size 10 1 Ring $17.95 A10-S11-D022 149 168496 FT9-PSA15-25 $21.95 Tree of Life Gold Tone Surgical Steel Double Flare Tunnel Plugs - 1" - Pair 2 Plugs Sale $43.90 A10-S11-D024 149 67502 CBR-1004 $10.95 Hollow Heart .925 Sterling Silver Captive Bead Ring - 16 Gauge CBR 10 Captive Ring , Daith $109.50 A10-S11-D031 149 180005 FT9-PSJ01-05 $11.95 Faux Turquoise Tribal Shield Surgical Steel Double Flare Plugs 4G - Pair 1 Plugs Sale $11.95 A10-S11-D032 149 67518 CBR-1020 $10.95 .925 Sterling Silver Hollow Star Vertical Captive Bead Ring - 16G 4 Captive Ring , Daith $43.80 A10-S11-D034 149 67520 CBR-1022 $10.95 .925 Sterling Silver Hollow Butterfly Vertical Captive Bead Ring - 16G 2 Captive Ring , Daith $21.90 A10-S11-D035 149 67521 CBR-1023 $8.99 .925 Sterling Silver Hollow Cross Vertical Captive Bead Ring - 16G 2 Captive Ring , Daith $17.98 A10-S11-D036 149 67522 NP-1001 $15.95 Triple CZ .925 Sterling Silver Nipple Piercing Barbell Shield 8 Nipple Ring $127.60 A10-S11-D038 149 -

Basic Facts About Stainless Steel

What is stainless steel ? Stainless steel is the generic name for a number of different steels used primarily for their resistance to corrosion. The one key element they all share is a certain minimum percentage (by mass) of chromium: 10.5%. Although other elements, particularly nickel and molybdenum, are added to improve corrosion resistance, chromium is always the deciding factor. The vast majority of steel produced in the world is carbon and alloy steel, with the more expensive stainless steels representing a small, but valuable niche market. What causes corrosion? Only metals such as gold and platinum are found naturally in a pure form - normal metals only exist in nature combined with other elements. Corrosion is therefore a natural phenomena, as nature seeks to combine together elements which man has produced in a pure form for his own use. Iron occurs naturally as iron ore. Pure iron is therefore unstable and wants to "rust"; that is, to combine with oxygen in the presence of water. Trains blown up in the Arabian desert in the First World War are still almost intact because of the dry rainless conditions. Iron ships sunk at very great depths rust at a very slow rate because of the low oxygen content of the sea water . The same ships wrecked on the beach, covered at high tide and exposed at low tide, would rust very rapidly. For most of the Iron Age, which began about 1000 BC, cast and wrought iron was used; iron with a high carbon content and various unrefined impurities. Steel did not begin to be produced in large quantities until the nineteenth century. -

Genital Piercings: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Implications for Urologists Thomas Nelius, Myrna L

Ambulatory and Office Urology Genital Piercings: Diagnostic and Therapeutic Implications for Urologists Thomas Nelius, Myrna L. Armstrong, Katherine Rinard, Cathy Young, LaMicha Hogan, and Elayne Angel OBJECTIVE To provide quantitative and qualitative data that will assist evidence-based decision making for men and women with genital piercings (GP) when they present to urologists in ambulatory clinics or office settings. Currently many persons with GP seek nonmedical advice. MATERIALS AND A comprehensive 35-year (1975-2010) longitudinal electronic literature search (MEDLINE, METHODS EMBASE, CINAHL, OVID) was conducted for all relevant articles discussing GP. RESULTS Authors of general body art literature tended to project many GP complications with potential statements of concern, drawing in overall piercings problems; then the information was further replicated. Few studies regarding GP clinical implications were located and more GP assumptions were noted. Only 17 cases, over 17 years, describe specific complications in the peer-reviewed literature, mainly from international sources (75%), and mostly with “Prince Albert” piercings (65%). Three cross-sectional studies provided further self-reported data. CONCLUSION Persons with GP still remain a hidden variable so no baseline figures assess the overall GP picture, but this review did gather more evidence about GP wearers and should stimulate further research, rather than collectively projecting general body piercing information onto those with GP. With an increase in GP, urologists need to know the specific differences, medical implica- tions, significant short- and long-term health risks, and patients concerns to treat and counsel patients in a culturally sensitive manner. Targeted educational strategies should be developed. Considering the amount of body modification, including GP, better legislation for public safety is overdue. -

Piercing-Aftercare

PIERCING AFTERCARE This advice sheet is given as your written reminder of the advised aftercare for your new piercing. The piercing procedure involves breaking the skin’s surface so there is always a potential risk for infection to occur afterwards. Your piercing should be treated as a wound initially and it is important that this advice is followed to minimise the risk of infection. If you have any problems at all with your piercing or if you would like assistance with a jewellery change then please call back and see us. Don’t be afraid to come back, we want you to be 100% happy with your piercing. MINIMISING INFECTION RISK ☺ Avoid touching the new piercing unnecessarily so that exposure to germs is reduced. ☺ Always thoroughly wash and dry your hands before touching your new piercing, or wear latex/nitrile gloves when cleaning it. ☺ If a dressing has been applied to your new piercing, leave it on for about one hour after the piercing was received and then you can remove the dressing and care for your piercing as advised below. ☺ Clean your piercing as advised by your piercer. ☺ For cleaning your piercing, you should use a saline solution. This can either be a shop-bought solution or a home-made solution of a quarter teaspoon of table salt in a pint of warm water or tea tree oil. Stay clear of and do NOT use surgical spirit, alcohol, soap, ointment or TCP. ☺ For cleaning oral piercings you should use a mild alcohol-free mouthwash eg Oral B Sensitive. ☺ Polyps can appear on new piercings; this is due to accidentally knocking the piercing site or pressure on the site. -

Patients with Oral/Facial Piercings

PATIENTS WITH ORAL/FACIAL PIERCINGS 2 Credits by Wendy Paquette, LPN, BS Erika Vanterainen, EFDA, LPN Home Study Solutions.com, Inc. P.O. Box 21517 St. Petersburg, FL 33742-1517 Phone 1-877-547-8933 Fax 1-727-546-3500 www.homestudysolutions.com November 2015 to December 2022 Home Study Solutions.com, Inc. is an ADA CERP recognized provider. 2/27/2000 to 5/31/2023 California CERP #3759 Florida CEBP #122 A National Continuing Education Provider Home Study Solutions.com, Inc. 1 Revised 2019 Copyrighted 1999 Home Study Solutions.com, Inc. Expiration date is 3 years from the original release date or last review date, whichever is most recent. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. If you have any questions or comments about this course, please e-mail [email protected] and put the name of the course on the subject line of the e-mail. We appreciate all feedback. Home Study Solutions.com, Inc. P.O. Box 21517 St. Petersburg, FL 33742-1517 Phone 1-877-547-8933 Fax 1-727-546-3500 www.homestudysolutions.com Printed in the USA Home Study Solutions.com, Inc. 2 PATIENTS WITH ORAL/FACIAL PIERCINGS Course Outline 1. OVERVIEW 2. ANATOMY OF THE TONGUE 3. ANATOMY OF THE LIP 4. THE PIERCING PROCEDURE • Complications and Risks Associated with Oral Jewelry • What role does tongue piercing play with tongue cancer? 5. -

Mineral Collecting Sites in North Carolina by W

.'.' .., Mineral Collecting Sites in North Carolina By W. F. Wilson and B. J. McKenzie RUTILE GUMMITE IN GARNET RUBY CORUNDUM GOLD TORBERNITE GARNET IN MICA ANATASE RUTILE AJTUNITE AND TORBERNITE THULITE AND PYRITE MONAZITE EMERALD CUPRITE SMOKY QUARTZ ZIRCON TORBERNITE ~/ UBRAR'l USE ONLV ,~O NOT REMOVE. fROM LIBRARY N. C. GEOLOGICAL SUHVEY Information Circular 24 Mineral Collecting Sites in North Carolina By W. F. Wilson and B. J. McKenzie Raleigh 1978 Second Printing 1980. Additional copies of this publication may be obtained from: North CarOlina Department of Natural Resources and Community Development Geological Survey Section P. O. Box 27687 ~ Raleigh. N. C. 27611 1823 --~- GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SECTION The Geological Survey Section shall, by law"...make such exami nation, survey, and mapping of the geology, mineralogy, and topo graphy of the state, including their industrial and economic utilization as it may consider necessary." In carrying out its duties under this law, the section promotes the wise conservation and use of mineral resources by industry, commerce, agriculture, and other governmental agencies for the general welfare of the citizens of North Carolina. The Section conducts a number of basic and applied research projects in environmental resource planning, mineral resource explora tion, mineral statistics, and systematic geologic mapping. Services constitute a major portion ofthe Sections's activities and include identi fying rock and mineral samples submitted by the citizens of the state and providing consulting services and specially prepared reports to other agencies that require geological information. The Geological Survey Section publishes results of research in a series of Bulletins, Economic Papers, Information Circulars, Educa tional Series, Geologic Maps, and Special Publications. -

Raymond & Leigh Danielle Austin

PRODUCT TRENDS, BUSINESS TIPS, NATIONAL TONGUE PIERCING DAY & INSTAGRAM FAVS Metal Mafia PIERCER SPOTLIGHT: RAYMOND & LEIGH DANIELLE AUSTIN of BODY JEWEL WITH 8 LOCATIONS ACROSS OHIO STATE Friday, August 14th is NATIONAL TONGUE PIERCING DAY! #nationaltonguepiercingday #nationalpiercingholidays #metalmafialove 14G Titanium Barbell W/ Semi Precious Stone Disc Internally Threaded Starting At $7.54 - TBRI14-CD Threadless Starting At $9.80 - TTBR14-CD 14G Titanium Barbell W/ Swarovski Gem Disc Internally Threaded Starting At $5.60 - TBRI14-GD Threadless Starting At $8.80 - TTBR14-GD @fallenangelokc @holepuncher213 Fallen Angel Tattoo & Body Piercing 14G Titanium Barbell W/ Dome Top 14G Titanium Barbell W/ Dome Top 14G ASTM F-67 Titanium Barbell Assortment Internally Threaded Starting At $5.46 - TBRI14-DM Internally Threaded Starting At $5.46 - TBRI14-DM Starting At $17.55 - ATBRE- Threadless Starting At $8.80 - TTBR14-DM Threadless Starting At $8.80 - TTBR14-DM 14G Threaded Barbell W Plain Balls 14G Steel Internally Threaded Barbell W Gem Balls Steel External Starting At $0.28 - SBRE14- 24 Piece Assortment Pack $58.00 - ASBRI145/85 Steel Internal Starting At $1.90 - SBRI14- @the.stabbing.russian Titanium Internal Starting At $5.40 - TBRI14- Read Street Tattoo Parlour ANODIZE ANY ASTM F-136 TITANIUM ITEM IN-HOUSE FOR JUST 30¢ EXTRA PER PIECE! Blue (BL) Bronze (BR) Blurple Dark Blue (DB) Dark Purple (DP) Golden (GO) Light Blue (LB) Light Purple (LP) Pink (PK) Purple (PR) Rosey Gold (RG) Yellow(YW) (Blue-Purple) (BP) 2 COPYRIGHT METAL MAFIA 2020 COPYRIGHT METAL MAFIA 2020 3 CONTENTS Septum Clickers 05 AUGUST METAL MAFIA One trend that's not leaving for sure is the septum piercing. -

Piercing Price List Red Tattoo and Piercing Leeds Corn Exchange 0113 2420413

Piercing Price List Red Tattoo and Piercing Leeds Corn exchange 0113 2420413 Ears Other Lobe - £12 BCR / Labret Nostril - £12 BCR/Plain & Jewell Stud Helix - £9 BCR / £12 Labret High Nostril - £15 Stud Tragus - £17 BCR / £20 Horseshoe Tongue - £30 Anti-Tragus - £17 BCR / £20 Horseshoe Lip - £20 BCR / £25 Labret Forward Helix - £17 BCR / £20 Horseshoe Medusa/Madonna – £25 Labret Rook - £17 BCR / £20 Curved Bar Navel - £20 BCR Snug - £20 Curved Bar /Horseshoe £25 Plain Curved Bar Conch - £20 Barbell / £25 BCR £28 Jewelled Curved Bar Orbital - £25 BCR/Horseshoe £30 Double Jewell Curved Bar Daith - £25 BCR/Horseshoe Nipple - £22 BCR / £40 Pair Industrial - £35 Barbell £26 Barbell / £50 Pair Eyebrow - £18 BCR / £20 Barbell We use Titanium as standard for all our piercings and we do offer a large variety of upgrade options. Just ask at reception for more information. PLEASE TURN OVER FOR MORE PRICES Other Cont. Dermal Anchor & Surface Bridge - £25 Barbell Dermal Anchors - £30 Plain/Jewelled Cheek - £30 Each / £50 Pair (First one full price, any after will be Septum - £30 BCR/Horseshoe £15 Each when done in the same sitting) Smiley - £20 BCR/Horseshoe Dermal Removal - £10 Frowny - £20 BCR/Horseshoe Surface – 1.2 £25 Tongue Web - £25 BCR/Horseshoe 1.6 £30 Vertical Lip - £30 Male Intimate (Saturdays Only) Female Intimate Prince Albert - £40 BCR/Horseshoe Clitoral Hood - £30 BCR Reverse PA - £40 BCR/Horseshoe £35 Curved Bar Frenum - £30 BCR/Barbell Fourchette - £30 Curved Bar Foreskin - £30 BCR/Horseshoe Christina - £30 P.T.F.E Guiche - £30 BCR/Horseshoe Triangle - £40 BCR/Horseshoe Hafada - £30 BCR/Horseshoe Labia - £30 BCR / £50 Pair Dydoe - £30 Curved Bar / £50 Pair x2 Pairs - £90 Surface - £30 x3 Pairs £125 Ladder – x 3 £80 (for more than 3 please ask for info) Piercings are done on a walk-in basis @redtattooleeds @danielle_redpiercing @brittany_redpiercing . -

(Licensing of Skin Piercing and Tattooing) Order 2006 Local Authority

THE CIVIC GOVERNMENT (SCOTLAND) ACT 1982 (LICENSING OF SKIN PIERCING AND TATTOOING) ORDER 2006 LOCAL AUTHORITY IMPLEMENTATION GUIDE Version 1.8 Scottish Licensing of Skin Piercing and Tattooing Working Group January 2018 Table of Contents PAGE CHAPTER 1 Introduction and Overview of the Order …………………………. 1 CHAPTER 2 Procedures Covered by the Order ……………………………….. 2 CHAPTER 3 Persons Covered by the Order …………………………………… 7 3.1 Persons or Premises – Licensing Requirements ……………………. 7 3.2 Excluded Persons ………………………………………………………. 9 3.2.1 Regulated Healthcare Professionals ………………………………. 9 3.2.2 Charities Offering Services Free-of-Charge ………………………. 10 CHAPTER 4 Requirements of the Order – Premises ………………………… 10 4.1 General State of Repair ……………………………………………….. 10 4.2 Physical Layout of Premises ………………………………………….. 10 4.3 Requirements of Waiting Area ………………………………………… 11 4.4 Requirements of the Treatment Room ………………………………… 12 CHAPTER 5 Requirements of the Order – Operator and Equipment ……… 15 5.1 The Operator ……………………………………………………………. 15 5.1.1 Cleanliness and Clothing ……………………………………………. 16 5.1.2 Conduct ……………………………………………………………….. 17 5.1.3 Training ……………………………………………………………….. 17 5.2 Equipment ……………………………………………………………… 18 5.2.1 Skin Preparation Equipment ……………………………………….. 19 5.2.2 Anaesthetics ………………………………………………………… 20 5.2.3 Needles ……………………………………………………………… 23 5.2.4 Body Piercing Jewellery …………………………………………… 23 5.2.5 Tattoo Inks ………………………………………………………….. 25 5.2.6 General Stock Requirements …………………………………….. 26 CHAPTER 6 Requirements of the Order – Client Information ……………. 27 6.1 Collection of Information on Client …………………………………….. 27 ii Licensing Implementation Guide – Version 1.8 – January 2018 6.1.1 Age …………………………………………………………………… 27 6.1.2 Medical History ……………………………………………………… 28 6.1.3 Consent Forms ……………………………………………………… 28 6.2 Provision of Information to Client ……………………………………… 29 CHAPTER 7 Requirements of the Order – Peripatetic Operators …………. -

Diplomarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Magisterarbeit „Phänomen Tattoo und Piercing – Zwischen Selbstfindung und Modeerscheinung“ Verfasserin Carina Nitsche angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Kultur- und Sozialwissenschaften (Mag.soc.) Wien, im März 2011 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A-307 Matrikelnummer: A0600791 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Kultur- und Sozialanthropologie Betreuer: Mag. Dr. Wittigo Keller Inhaltsverzeichnis VORWORT ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 EINFÜHRUNG ................................................................................................................................................ 5 PHÄNOMEN KÖRPERKUNST........................................................................................................................... 8 BEGRIFFSERKLÄRUNG.............................................................................................................................................. 10 ARTEN ................................................................................................................................................................. 11 Tatauierungen und Skarifizierungen ............................................................................................................ 11 Piercing und Perforation .............................................................................................................................. -

Complications of Oral Piercing

Y T E I C O S L BALKAN JOURNAL OF STOMATOLOGY A ISSN 1107 - 1141 IC G LO TO STOMA Complications of Oral Piercing SUMMARY A. Dermata1, A. Arhakis2 Over the last decade, piercing of the tongue, lip or cheeks has grown 1General Dental Practitioner in popularity, especially among adolescents and young adults. Oral 2Aristotle University of Thessaloniki piercing usually involves the lips, cheeks, tongue or uvula, with the tongue Dental School, Department of Paediatric Dentistry as the most commonly pierced. It is possible for people with jewellery in Thessaloniki, Greece the intraoral and perioral regions to experience problems, such as pain, infection at the site of the piercing, transmission of systemic infections, endocarditis, oedema, airway problems, aspiration of the jewellery, allergy, bleeding, nerve damage, cracking of teeth and restorations, trauma of the gingiva or mucosa, and Ludwig’s angina, as well as changes in speech, mastication and swallowing, or stimulation of salivary flow. With the increased number of patients with pierced intra- and peri-oral sites, dentists should be prepared to address issues, such as potential damage to the teeth and gingiva, and risk of oral infection that could arise as a result of piercing. As general knowledge about this is poor, patients should be educated regarding the dangers that may follow piercing of the oral cavity. LITERATURE REVIEW (LR) Keywords: Oral Piercings; Complications Balk J Stom, 2013; 17:117-121 Introduction are the tongue and lips, but other areas may also be used for piercing, such as the cheek, uvula, and lingual Body piercing is a form of body art or modification, frenum1,7,9. -

Skin Friendly Jewellery News Spring/Summer 2021 Medical Ear

MADE IN SWEDEN Skin friendly jewellery news spring/summer 2021 Medical ear & nose piercing VALID FROM FEBRUARY 2021 EURO 1 Do your customers like beautiful jewellery? New So do we. We also think that they should be able to wear it without having to worry about nickel, cadmium, lead or any other inappropriate materials. And that their children or grandchildren should be able to do the same. That is why Blomdahl’s jewellery and ear and nose piercing method exists, a safe way to look good every day. For you, with care. Be inspired by our skin friendly new styles New CONTENT: 3 NEWS 13 ACCESSORIES 14 MEDICAL EAR PIERCING 18 MEDICAL NOSE PIERCINGG 19 ACCESSORIES, CLEANSING ETC 20 PRODUCT EXPOSURE 23 MARKETING ew See the entire assortment N on b2b.blomdahl.com 2 3 SKIN FRIENDLY JEWELLERY SKIN FRIENDLY JEWELLERY 33-2490-0800 S, O 33-2390-0800 G, O NEWS Butterfly SPRING/SUMMER 8 MM 2021 16 MM, 31-12090-1600 NT, N 16 MM, 31-13090-1600 GT, N 17 MM, 31-12090-1700 NT, N 17 MM, 31-13090-1700 GT, N 18 MM, 31-12090-1800 NT, N 18 MM, 31-13090-1800 GT, N 19 MM, 31-12090-1900 NT, N 19 MM, 31-13090-1900 GT, N BUTTERFLY BUTTERFLY 15-1490-00 ST, 8 MM I 15-1390-00 GT, 8 MM I From the existing assortment From the existing assortment 32-2390-0800 G, N 32-2490-0800 S, N PRICE GROUP PRICE/ PAIR REC RETAIL PRICE I € 21,60 € 49,00 N € 38,60 € 90,00 O € 44,20 € 102,00 GT= Golden Titanium ST= Silver Titanium NT= Natural Titanium G: bracelet or necklace with a gold coloured, skin friendly ceramic coating.