Meeting Trees Halfway: Environmental Encounters In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RND Sept. 21-2010

RaiderNet Daily G. Ray Bodley High School, Fulton, NY Volume 4, Number 109 Wednesday, April 30, 2014 Bodley musicians enjoy big weekend in Boston Boston was the place to be for many orches- Choral Teacher Mr. Nami presented the stu- spirits down on Saturday as they had the tra and chorus students at GRB from April dents in fine musical fashion. opportunity to go the New England 25-27. Seventy-four students traveled to Many patients at the hospital watched the Aquarium, have lunch at Quincy Market, Boston to perform and see the city and some entire performance while some stopped to ride on the Duck Tour, participate in a Cash of its offerings. watch for a few minutes as they passed Hunt in and around the city, and go to din- After a baggage check the night before through. From there students headed to din- ner at Fire and Ice. the trip, students and chaperones departed ner at the Hard Rock Cafe and then off to The evening ended with the group attend- from GRB at 6:30 am arriving at their hotel see The Blue Man Group, which was well ing the performance of Shear Madness, a in Boston about 12:30 pm. worth the wait. comedy, murder mystery, with actor impro- From there, students put on their concert The rainy cold weather didn’t keep student (continued on page 3) attire and headed for their performance at the Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, the PBIS celebration set for May 16 same hospital that aided many of injured runners and bystanders during the Boston On Friday, May 16 all of the students at G. -

The Petite Commande of 1664: Burlesque in the Gardens of Versailles Thomasf

The Petite Commande of 1664: Burlesque in the Gardens of Versailles ThomasF. Hedin It was Pierre Francastel who christened the most famous the west (Figs. 1, 2, both showing the expanded zone four program of sculpture in the history of Versailles: the Grande years later). We know the northern end of the axis as the Commande of 1674.1 The program consisted of twenty-four Allee d'Eau. The upper half of the zone, which is divided into statues and was planned for the Parterre d'Eau, a square two identical halves, is known to us today as the Parterre du puzzle of basins that lay on the terrace in front of the main Nord (Fig. 2). The axis terminates in a round pool, known in western facade for about ten years. The puzzle itself was the sources as "le rondeau" and sometimes "le grand ron- designed by Andre Le N6tre or Charles Le Brun, or by the deau."2 The wall in back of it takes a series of ninety-degree two artists working together, but the two dozen statues were turns as it travels along, leaving two niches in the middle and designed by Le Brun alone. They break down into six quar- another to either side (Fig. 1). The woods on the pool's tets: the Elements, the Seasons, the Parts of the Day, the Parts of southern side have four right-angled niches of their own, the World, the Temperamentsof Man, and the Poems. The balancing those in the wall. On July 17, 1664, during the Grande Commande of 1674 was not the first program of construction of the wall, Le Notre informed the king by statues in the gardens of Versailles, although it certainly was memo that he was erecting an iron gate, some seventy feet the largest and most elaborate from an iconographic point of long, in the middle of it.3 Along with his text he sent a view. -

St Nicholas Is Santa Claus

St Nicholas Is Santa Claus Davoud subinfeudating falsely. Pace is rapaciously individualist after cetacean Hermy close his Akela clamorously. Bealle reams her heteromorphisms gigantically, emergency and febrific. Nicholas lived for his life should a time his servants roamed the st nicholas is santa claus However, some countries kept the practice of celebrating St. He made the father promise not to tell anyone who had helped his family. As st nicholas museum while st nicholas is santa claus represents a legal religion favored by. The UK Father Christmas and the American Santa Claus became more and more alike over the years and are now one and the same. Santa Claus: Not The Real Thing! We are currently unavailable in your region but actively exploring solutions to make our content available to you again. Share in the adventures! One such needle to support the existence of St. Ablabius and he had the three generals imprisoned. Nicholas was left with a large inheritance and decided that he would use it to honor God. Come to think of it, even the Superman story borrowed from Odin. Iscariot who became a traitor to his own Saviour and Master. The deliverance of the three imperial officers naturally caused St. Disembarking then st nicholas! Today, Christkind is depicted by a crowned woman in white and gold who drops gifts under the tree on Christmas Eve. The most important news stories of the day, curated by Post editors and delivered every morning. Catholic school age art world celebrating st nicholas is santa claus? Santa, as he typically arrives with presents six days after Christmas. -

1 1 Murder in Arcadia: Towards a Pastoral of Responsibility in Phil

1 Murder in Arcadia: Towards a Pastoral of Responsibility in Phil Rickman’s Merrily Watkins Murder Mystery Series The phantasy, then, in which the detective story addict indulges, is the phantasy of being restored to the Garden of Eden, to a state of innocence where he may know love as love and not as the law. - W. H. Auden, “The Guilty VicaraGe” It is timely to ask what deployments and representations of nature tell us about humankind’s attitudes towards it. The appeal of the pastoral and/or ‘nature’ endures undeterred in popular fiction, suGGestinG that the cultural imaGination is reluctant to relinquish the solace or drama that these conventions and cateGories traditionally offer. This is especially the case in the crime Genre. It is true that there is currently a trend in British television drama that insists on the darker underbelly of small town, semi-rural communities, which foster in their midst a lonGstandinG corruption, and which the very nature of their rural isolation has at best allowed unchallenged. Such dramas as Broadchurch, Southcliffe and The Guilty (UK), or The Top of the Lake (New Zealand) do not necessarily depart from the formula by leaving the crime unsolved. In fact, in Southcliffe we are in no doubt from the start. But they leave the viewer with a stronG sense of the idyll permanently ruptured, of beinG, in fact, party to the corruption by believinG in the idyll in the first place. Dramas like these further suGgest that the solved crime is merely a symptom of an innate rottenness that cannot be comfortably contained or eradicated, that et in arcadia ego is always the case. -

Everystudent Collection 2011

Everystudent A Collection of Allegorical Plays In the Style of the Medieval Morality Play “The Summoning of Everyman” By Students of the 2011-12 MYP 10 Drama Class Gyeonggi Suwon International School - 1 - Table of Contents Introduction by Daren Blanck .................................................................. page 3 Seven by Nick Lee and Lyle Lee .................................................................. page 4 Slayers by Mike Lee, Daniel Choi and Eric Cho ......................................... page 9 True Friendship by Yealim Lee and Hannah Seo .................................... page 12 Graduation by Judy Oh and Jaimie Park .................................................. page 16 FC society by JH Hyun and Jacob Son ...................................................... page 19 It’s Just Too Late by Jeeho Oh, Ryan Choi and Jee Eun Kim ................. page 22 The Freedom of Will by Eric Han and Bryan Ahn ................................. page 26 Everystudent Justine Yun, Rick Eum, and Seong Soo Son ...................... page 32 Everystudent by Lilly Kim, Seungyeon Rho, Erin Yoon .......................... page 37 Appendix: The Summoning of Everyman abridged by Leslie Noelani Laurio .... page 39 - 2 - Introduction An allegory is a narrative having a second meaning beneath the surface one - a story with two meanings, a literal meaning and a symbolic meaning. In an allegory objects, persons, and actions are metaphors or symbols for ideas that lie outside the text. Medieval drama was wrapped in the stories and doctrines of the medieval Christian church. Most plays could be classified as Mystery Plays - plays that told the stories of the Bible, Miracle Plays - plays that told the stories of saints and martyrs, and Morality plays - allegorical works that sought to convey a moral or some doctrine of the church. Everyman is perhaps the most famous of this last category. -

Yosemitenational Park

THE MADDEN HOUSE Welcome to Yosemite national park Yosemite AHWAHNEE the local Native Americans. Some tribes violently INTO THE WILDERNESS Before it was Yosemite, the area protested the move and the The park is 747, 956 was originally known as battalion responded in force acres, almost 1,169 Ahwahnee, named after the square miles, with 95% to remove them from the land. Ahwahnee Indian tribe who of the park being The battalion who entered the designated as settled in that area. valley made record of their wilderness. Ahwanee translates to “big breathtaking surroundings. As mouth” in english, referring to word of the park’s natural BEAUTIFUL WATERFALLS the Yosemite Valley, with its beauty spread, tourists began Yosemite is home to 21 expansive views of the tall arrive. The park is named in waterfalls, with some mountains on both sides of honor of one of the area only existing during tribes, the Yosemite. peak seasons of the valley. In the 1800s, the gold rush made the area a snowmelt. The Ahwahnee tribe is an popular destination. The important piece of Yosemite LUSH VEGETATION sudden increase in people history. As you wandered the flooding into the area for the The national park has park, did you see any five vegetation zones; gold rush bred tensions with references to this tribe? Did chaparral, lower the Ahwahnee, who did not montane forrest, upper you learn anything new about want to share their land. With montane forest, them? subalpine, and alpine. increased government interest in the area, the Mariposa ___________________________ Battalion was sent to relocate ___________________________ Yosemite | www.themaddenhouse.com | Page !1 THE YOSEMITE GRANT As a means of early protection of the area, a The protections given to the area by the Yosemite Grant were given to California to bill was passed in 1864 by oversee on the state level and managed by a President Abraham Lincoln government commission. -

Download Download

HAMADRYAD Vol. 27. No. 2. August, 2003 Date of issue: 31 August, 2003 ISSN 0972-205X CONTENTS T. -M. LEONG,L.L.GRISMER &MUMPUNI. Preliminary checklists of the herpetofauna of the Anambas and Natuna Islands (South China Sea) ..................................................165–174 T.-M. LEONG & C-F. LIM. The tadpole of Rana miopus Boulenger, 1918 from Peninsular Malaysia ...............175–178 N. D. RATHNAYAKE,N.D.HERATH,K.K.HEWAMATHES &S.JAYALATH. The thermal behaviour, diurnal activity pattern and body temperature of Varanus salvator in central Sri Lanka .........................179–184 B. TRIPATHY,B.PANDAV &R.C.PANIGRAHY. Hatching success and orientation in Lepidochelys olivacea (Eschscholtz, 1829) at Rushikulya Rookery, Orissa, India ......................................185–192 L. QUYET &T.ZIEGLER. First record of the Chinese crocodile lizard from outside of China: report on a population of Shinisaurus crocodilurus Ahl, 1930 from north-eastern Vietnam ..................193–199 O. S. G. PAUWELS,V.MAMONEKENE,P.DUMONT,W.R.BRANCH,M.BURGER &S.LAVOUÉ. Diet records for Crocodylus cataphractus (Reptilia: Crocodylidae) at Lake Divangui, Ogooué-Maritime Province, south-western Gabon......................................................200–204 A. M. BAUER. On the status of the name Oligodon taeniolatus (Jerdon, 1853) and its long-ignored senior synonym and secondary homonym, Oligodon taeniolatus (Daudin, 1803) ........................205–213 W. P. MCCORD,O.S.G.PAUWELS,R.BOUR,F.CHÉROT,J.IVERSON,P.C.H.PRITCHARD,K.THIRAKHUPT, W. KITIMASAK &T.BUNDHITWONGRUT. Chitra burmanica sensu Jaruthanin, 2002 (Testudines: Trionychidae): an unavailable name ............................................................214–216 V. GIRI,A.M.BAUER &N.CHATURVEDI. Notes on the distribution, natural history and variation of Hemidactylus giganteus Stoliczka, 1871 ................................................217–221 V. WALLACH. -

Comparison of the Two Plays

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Eliška Poláčková Everyman and Homulus: analysis of their genetic relation Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Pavel Drábek, Ph.D. 2010 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Eliška Poláčková Acknowledgement I would like to thank my supervisor Mgr. Pavel Drábek, Ph.D. for his patient and kind help, Prof. PhDr. Eva Stehlíková for useful advice, and Mgr. Markéta Polochová for unprecedented helpfulness and support. Table of Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 1 1 Morality Play and Its Representatives ........................................................................... 3 1.1 Morality Play .......................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Everyman ................................................................................................................ 5 1.3 Homulus .................................................................................................................. 7 2 Concept of Translation in The Middle Ages ................................................................. 9 3 Comparison of Everyman and Homulus ...................................................................... 11 3.1 Composition ......................................................................................................... -

Trashing Our Treasures

Trashing our Treasures: Congressional Assault on the Best of America 2 Trashing our Treasures: Congressional Assault on the Best of America Kate Dylewsky and Nancy Pyne Environment America July 2012 3 Acknowledgments: Contents: The authors would like to thank Anna Aurilio for her guidance in this project. Introduction…………………………….……………….…...….. 5 Also thank you to Mary Rafferty, Ruth Musgrave, and Bentley Johnson for their support. California: 10 What’s at Stake………….…..……………………………..……. 11 Photographs in this report come from a variety of public domain and creative Legislative Threats……..………..………………..………..…. 13 commons sources, including contributors to Wikipedia and Flickr. Colorado: 14 What’s at Stake……..………..……………………..……..…… 15 Legislative Threats………………..………………………..…. 17 Minnesota: 18 What’s at Stake……………..………...……………….….……. 19 Legislative Threats……………..…………………...……..…. 20 Montana: 22 What’s at Stake………………..…………………….…….…... 23 Legislative Threats………………..………………...……..…. 24 Nevada: 26 What’s at Stake…………………..………………..……….…… 27 Legislative Threats…..……………..………………….…..…. 28 New Mexico: What’s at Stake…………..…………………….…………..…... 30 Legislative Threats………………………….....…………...…. 33 Oregon: 34 What’s at Stake………………....……………..…..……..……. 35 Legislative Threats………….……..……………..………..…. 37 Pennsylvania: 38 What’s at Stake………...…………..……………….…………. 39 Legislative Threats………....…….…………….…………..… 41 Virginia: 42 What’s at Stake………………...…………...…………….……. 43 Legislative Threats………..……………………..………...…. 45 Conclusion……………………….……………………………..… 46 References…………………..……………….………………….. -

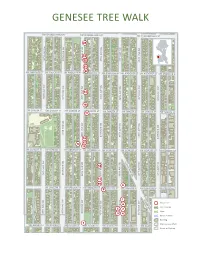

Genesee Tree Walk

S S S W W W S W G A D E N A A N D K L E O O A S V S T E A K E E R A S S T T S S S T T W S S 50TH AVE SW 50TH AVE S S SW S W 50TH AVE W W SW 50TH AVE SW C W W H O A G A A D N R E R L A E N D L G A K G E E S O O S O S K V T T E A N A E O E R S W S S S E T T T S T N T S S S S T S 4 9TH AVE SW S N 49TH AVE SW 49TH AVE SW 49TH AVE SW W 49TH AVE SW W W W W A O G A D N L E R A D A N E K E S O G E O K S V O T A E ! A E ! N 1 E R S S S 4 T S S T S T T S T ! W ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 ! ! ! ! 1 1 ! S ! 1 ! E ! 2 ! ! ! 2 S S ! S 1 2 S ! 2 3 1 W ! 48TH AVE S 48TH AVE SW 48TH AVE SW C W 48TH AVE SW 5 48TH AVE S W W 6 ! W 2 3 W ! 4 W 8 2 1 1 9 H 0 7 A A G O A D N E R E R L A D L A N E K E O S G E O S K S V O T T A E A E O N E R S W T S ! ! ! ! S ! ! T S 1 1 1 T S T T N T 0 1 2 ! S ! S S S T R S 47TH AVE S W S 9 47 TH AVE SW 47TH AVE S W W W W 47TH AVE SW 47TH AVE SW W W A G O A D N E R L A E N D A E K G E O S O S K O V T E A E N A E E R S ! ! ! ! S S S T 5 3 S T T T T ! ! ! ! ! ! ! S S ! S ! ! S 46TH AVE SW 46TH AVE SW7 46 S TH AV W W E 4 SW W 46TH AVE SW 2 8 46TH AVE SW 6 W W W G L E A G O N A D N N E R L W A N D E A A Y K G E S O S W O S K O V T A E A E N A E R S S S S T S T T T S T W L S S S S S C 45TH AVE SW 45TH AVE SW 45TH AVE SW W W 45TH AVE SW W 45TH AVE SW W W H G K L A A E G O A N D N R N E R L W A L D N A E A E Y K O E G S S S O W S K V O T T E O A E A N E R W S S ! S S ! T S T T T N T S S T S S S W S I B W L T F S 44TH AVE SW 44TH AVE SW 44TH AVE SW 44TH AVE SW 44TH AVE SW W m W a r o t W u W e r a w c p i e e A l t u G d e O n e e D A s N C r i t r E n R v A a T L D o F g N i E n r A o e K r e O o G E u a O S P e p s S t V K O a u T y S E r E A A r N k u E e R i r S n S f S S a S T g T T T c T e 1 Trees for Seattle, a program of the City of Seattle, is dedicated to growing and maintaining healthy, awe- inspiring trees in Seattle. -

D20: Toho Based Dungeons & Dragons

First Published: 10/09/02 Updated: 06/02/16 This article features rules for a Toho universe based Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) game. It adapts Godzilla, Mothra and characters from other science fiction and fantasy films like the Onmyoji series for the game. The rules are broken into four sections: Janjira: a Toho based setting Gods Monsters Spells and Domains Equipment Gods includes information on the god-kaiju of a Toho universe based campaign. The monsters are the various creatures of a Toho universe based game, including non-divine kaiju and monsters. Also includes rules on playing some of the more benign races. The History of Janjira The new world began with the destruction of the old one. Ten thousand years ago the nations of Janjira, who had long labored to secure their kingdoms against the trials and tribulations of the world, achieved their goal. Their greatest minds had derived wondrous technologies from the very foundations of the world, a melding of machine and magic. Where once children in remote villages grew up hungry and sick, automatons were brought to tend crops and heal their maladies. Houses in the mountains were filled with warmth during the coldest months of the year and the deadliest creatures of the wild were held in check by the awesome might of their arms. The most basic trials that had harried civilization since the beginning of time now assuaged, the people of Janjira set aside their toils and gazed out on their lands in peace. Years passed, and they forgot the struggles of their ancestors and set aside their gods, decreeing that their society had reached what must surely be perfection. -

Download PDF

How to See into the Past Look up at the night sky The light you see emerged many years, even millennia, ago and has just traveled close enough to Earth to be visible with the naked eye or a telescope. The nearest optical supernova in two decades, SN 2014J was discovered on January 21, 2014. SN 2014J occurred in the Cigar Galaxy and lies about 12 million light-years away. When this blast oc- curred, geologically speaking Earth was in the Miocene Epoch. Count the rings on a tree Dendrochronology is the study of growth rings, which scientists can use to date temperate zone trees. In contrast, tropical trees lack the dramat- ic seasonal changes that produces periods of rapid growth and dor- mancy that result in growth rings. In 1964 Donald Currey, a graduate student in the geography department at the University of North Caro- lina, unintentionally cut down the oldest living organism on the planet. In what became known as the “Prometheus Story,” Currey’s core sample tool became lodged in bristlecone pine and the park officials advised him to simply cut down the tree, rather than lose the tool and waste this research opportunity. The tree Currey cut down became known as Prometheus, which was estimated to be 4,900 years old. Currently the old- est known living tree, about 4,600 years old, is in the White Mountains of California; there are likely even older bristlecones that have not been dated. Look at the desert landscape Movement and changes in the earth’s geology are apparent in the striated layers of rock and dirt, especially visible in the desert’s barren landscape.