Audience Engagement and Monetisation of Creative Content in Digital Environments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Q2 2021 Management's Discussion & Analysis

Share Information Investor Information Q At August 26, 2021, the All financial reports, news SIX U Company had 32,024,314 releases and corporate common shares outstanding information can be accessed on A M ONTHS and stock options exercisable our website at R E NDED for 2,020,530 additional www.wowunlimited.co common shares and warrants T JUNE 3 0 Contact Information 2 exercisable into 900,000 E 2 0 2 1 common shares. Investor Relations 200 – 2025 West Broadway R 2021 Vancouver, BC, Canada V6J 1Z6 [email protected] MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS This Management’s Discussion and Analysis (“MD&A”) is dated August 26, 2021 and is intended to assist in understanding the results of operations and financial condition of Wow Unlimited Media Inc. as at and for the three and six months ended June 30, 2021, and should be read in conjunction with the unaudited condensed interim consolidated financial statements and accompanying notes for the three and six months ended June 30, 2021, and other public disclosure documents of Wow Unlimited Media Inc., including its previously filed December 31, 2020, annual consolidated financial statements. Past performance may not be indicative of future performance. Unless otherwise noted, all amounts are reported in Canadian dollars, the Company’s functional currency, and have been prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”). Throughout the MD&A reference to “Wow Unlimited” or the “Company” refers to Wow Unlimited Media Inc. and its subsidiary entities. Additional information, including other publicly filed documents relating to the Company are available through the internet on the Canadian Securities Administrators’ System for Electronic Document Analysis and Retrieval (“SEDAR”), which can be accessed at www.sedar.com. -

Cartoon Digital

cartoon digital 6-8 December 2016 Munich (Germany) Creating Entertainment for Connected Screens Top speakers • Market trends • Case studies • Networking www.cartoon-media.eu pitching event for animated transmedia projects cRtOn 3 29 31 May 2017 www.cartoon-media.eu PARTNERS CARTOON DIGITAL IS ORGANISED BY WITH THE SUPPORT OF IN COLLABORATION WITH CARTOON IS SPONSORED BY 3 Ilse Aigner Bavarian State Minister of Economic Affairs and Media, Energy and Technology Deputy Minister-President of Bavaria Dear Cartoon Digital Seminar Attendants, n behalf of the Bavarian Government I warmly welcome you to Cartoon Digital in Munich, Bavaria’s cosmopolitan capital. O It has been a long-standing tradition to host a cartoon program event here in Munich. Munich is just the right venue: the local television stations and producers, special service providers for VFX and animation, the renowned University of Television and Film Munich (HFF) as well as other elite universities and, last but not least, an active and innovative games industry make Munich a first class location for animation film and television productions in Germany. The State of Bavaria with its film funding program run by the FilmFernsehFonds Bayern (FFF Bayern) contributes highly towards maintaining this leading position. The FFF Bayern disburses funding totaling 33 million — 4.7 million € of this funding is specifically allocated to the technically highly demanding and staff-intensive VFX and animation services and to international co-productions. In addition, there is a program that is dedicated to the games industry in Bavaria. This program will be further extended in the following years, and other media innovations will also be funded in future. -

Free-Digital-Preview.Pdf

THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ $7.95 U.S. 01> 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net THE BUSINESS, TECHNOLOGY & ART OF ANIMATION AND VFX January 2013 ™ The Return of The Snowman and The Littlest Pet Shop + From Up on The Visual Wonders Poppy Hill: of Life of Pi Goro Miyazaki’s $7.95 U.S. 01> Valentine to a Gone-by Era 0 74470 82258 5 www.animationmagazine.net 4 www.animationmagazine.net january 13 Volume 27, Issue 1, Number 226, January 2013 Content 12 22 44 Frame-by-Frame Oscars ‘13 Games 8 January Planner...Books We Love 26 10 Things We Loved About 2012! 46 Oswald and Mickey Together Again! 27 The Winning Scores Game designer Warren Spector spills the beans on the new The composers of some of the best animated soundtracks Epic Mickey 2 release and tells us how much he loved Features of the year discuss their craft and inspirations. [by Ramin playing with older Disney characters and long-forgotten 12 A Valentine to a Vanished Era Zahed] park attractions. Goro Miyazaki’s delicate, coming-of-age movie From Up on Poppy Hill offers a welcome respite from the loud, CG world of most American movies. [by Charles Solomon] Television Visual FX 48 Building a Beguiling Bengal Tiger 30 The Next Little Big Thing? VFX supervisor Bill Westenhofer discusses some of the The Hub launches its latest franchise revamp with fashion- mind-blowing visual effects of Ang Lee’s Life of Pi. [by Events forward The Littlest Pet Shop. -

Q2 2018 Management`S Discussion & Analysis Wow Unlimited Media Inc

Share Information Investor Information Q T H R E E At August 28, 2018, the All financial reports, news U Company had 26,752,131 releases and corporate AND S I X common shares outstanding information can be accessed on A M O N T H S and stock options exercisable our website at R for 2,343,897 additional www.wowunlimited.co 2 E N D E D common shares and warrants T Contact Information exercisable into 263,786 J UNE 3 0 E common shares. Investor Relations 200 – 2025 West Broadway R 2 0 1 8 2018 Vancouver, BC, Canada V6J 1V6 [email protected] . MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS This Management’s Discussion and Analysis (“MD&A”) is dated August 28, 2018 and is intended to assist in understanding the results of operations and financial condition of Wow Unlimited Media Inc. as at and for the three and six months ended June 30, 2018 and should be read in conjunction with the unaudited condensed interim consolidated financial statements and accompanying notes for the three and six months ended June 30, 2018 and other public disclosure documents of Wow Unlimited Media Inc., including its previously filed December 31, 2017 annual consolidated financial statements. Past performance may not be indicative of future performance. Unless otherwise noted, all amounts are reported in Canadian dollars, the Company’s functional currency, and have been prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”). Throughout the MD&A reference to Wow Unlimited or the Company refers to Wow Unlimited Media Inc. and its subsidiary entities. -

Download Bee & Puppycat Vol. 2 (Bee and Puppycat)

Download: Bee & PuppyCat Vol. 2 (Bee and PuppyCat) PDF Free [561.Book] Download Bee & PuppyCat Vol. 2 (Bee and PuppyCat) PDF By various Bee & PuppyCat Vol. 2 (Bee and PuppyCat) you can download free book and read Bee & PuppyCat Vol. 2 (Bee and PuppyCat) for free here. Do you want to search free download Bee & PuppyCat Vol. 2 (Bee and PuppyCat) or free read online? If yes you visit a website that really true. If you want to download this ebook, i provide downloads as a pdf, kindle, word, txt, ppt, rar and zip. Download pdf #Bee & PuppyCat Vol. 2 (Bee and PuppyCat) | #287982 in Books | BOOM | 2016-02-09 | 2016-02-09 | Original language: English | PDF # 1 | 10.19 x .30 x 6.63l, .0 | File type: PDF | 128 pages | BOOM | |0 of 0 people found the following review helpful.| Beyond Satisfied! | By Jensen Bee |I love Bee and Puppycat so much that it makes me feel a certain kind of happiness I've never felt for any other show before. The book came in perfectly and there was no dents or bends I was beyond satisfied with this. I've brought so many things involving this series and I don't ever regret buying a single thing! If you love Bee an | About the Author | Natasha Allegri is a storyboard revisionist who works on the Adventure Time cartoon series and was responsible for designing gender revised versions of the characters for the Show, including Fionna and Cake. Bee just wants to enjoy the good things in life like delicious food and the sweet entertainment of television, too bad money gets in the way. -

283123939-Rocket-Dog-Pitch

Like most people, as a kid Rocket Dog is a turbo- you probably wished for a charged animated series of sympathetic pet whose eleven-minute cartoons fiery rocket-butt gave her bounding squarely towards the power to fly. Good every seven-to eleven-year- thing for you your wish old who loves a good laugh never came true. (and to anyone who’s subversive enough to enjoy the mayhem caused by a certifiably insane canine). Bob is our human hero. A 12-year-old kid, he’s got those qualities you see in a lot of boys his age. He’s competitive, a bit gullible, believes he’s a natural leader (yet works himself to death to fit in), gets nervous around pretty girls, and is able to recognize godawful ideas only in hindsight. Bob would be well-satisfied to be seen as a natural leader but NO ONE with a shred of common sense will follow him. Rocket Dog follows him everywhere. Not that that’s a good thing. It’s those everyday things Bob wants—popularity, the like of a cute girl, racing bike—that are the drivers of our stories. In the long history of dogs, if ever there were a dependable, focused, proud, trustworthy, steadfast companion, it sure as heck isn’t Rocket Dog. (Maybe you’re thinking of her idol, screen star Bonnie?) Oh, sure, Rocket Dog is loyal to Bob—loyal to a neurotic, psychoballistic fault. It’s her over- zealous, frenzied, tongue-wagging determination to help get Bob what he wants that transforms his customary, dime-a-dozen days into epic, one-of-a-kind disasters. -

Bee and Puppycat: Vol. 2 Free Download

BEE AND PUPPYCAT: VOL. 2 FREE DOWNLOAD Natasha Allegri | 128 pages | 30 Jun 2016 | Boom! Studios | 9781608867769 | English | Los Angeles, United States Bee and PuppyCat Ser.: Bee and PuppyCat Vol. 2 (2016, Trade Paperback) Friend Reviews. Frederator Studios. I have no connection to the series so this left me a bit cold - I understand this is aimed at the fans of the show. Bee and PuppyCat: Vol. 2 love all the illustrators who are a part of these comics ;-; their styles are so different and it just spices things up a little bit. I love the different artstyles in the book as well. With no luck in finding a new job, PuppyCat offers Bee some temp work if they report to Fishbowl Space. Feb 17, Lata rated it it was ok Shelves: scifi-fantasyauth-fxread. Bleeding Cool. The other stories are cute and fun, but I Bee and PuppyCat: Vol. 2 really looking to see where that ongoing story was headed. In horror, Bee spits her gum into the cherry and gives the rest to the farmer, leaving him and his animals to devour each other. Variation s. Bee celebrates her birthday with her "Dad Box", a creation by her father to help her feel less lonely. Oh well. Bee and PuppyCat save the day Sort of! Bee tries to free him by activating TempBot's letter, but she is transported along with Deckard instead. She clicks it open, only to find loose pieces and an off-key tune. How can you not love an aimless twenty-something who is obsessed with fo I got this for my year-old for his birthday, but honestly, it was as much for me as him. -

About Reaching Children Through Entertainment a Publication of Brunico Communications Inc.1996 - 2006

US$7.95 in the U.S. CA$8.95 in Canada 1 US$9.95 outside of Canada & the U.S. May 2006 ® About reaching children through entertainment A Publication of Brunico Communications Inc.1996 - 2006 www.stelorproductions.com NTED IN USPS CANADA Approved Polywrap AFSM 100 NUMBER 40050265 PRI 40050265 NUMBER CANADA POST AGREEMENT POST CANADA Redefi ning Trust In Internet Security.™ Approved by Parents. Loved by Kids. Protected by PiXkey.™ Stelor Productions © 2006 The Googles from Goo are a creation of Steven A. Silvers KKS3996.STELOR.inddS3996.STELOR.indd 1 44/26/06/26/06 88:42:04:42:04 PMPM HHOWOW WWILLILL YYOUOU MAKEMAKE TTHEHE BESTBEST UUSESE OOFF DDIGITALIGITAL TTRENDSRENDS AANDND GGROWROW YYOUROUR BBRANDRAND AACROSSCROSS EEMERGINGMERGING MMEDIAEDIA PPLATFORMS?LATFORMS? WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW TO GROW YOUR KIDS BRAND ACROSS EMERGING MEDIA PLATFORMS SSPEAKERSPEAKERS IINCLUDE:NCLUDE: Jacqueline Moen Paul Marcum VP & GM, KOL GM, Youth Content AOL Yahoo! John Evershed Co-founder & CEO Larry Seidman Doug Murphy Mondo Media CEO EVP Business Development Dimensional Branding Group Nelvana Ltd. Paul Jelinek Robin Fisher Roffer Deron Triff VP, Digital Media Products CEO, Chief Creative Offi cer VP, Business Development Nickelodeon Big Fish Marketing, Inc Scholastic Media Presented by: The Must Attend Event for Execs Looking to Build Kids Entertainment Brands, Including: Supported by: • Brand / IP Managers • Marketers • Licensors • Content Producers / Distributors • Advertising & Promotion Agencies ™Brand Building in the Kids Digital Space title, tagline and logo are trademarks of, • Digital Media Executives and the event is produced by Brunico Marketing Inc. *$100 discount off full one-day conference rate of $750 by April 17, 2006. -

Shawn Patterson

SHAWN PATTERSON SELECTED CREDITS MAKING APES: THE ARTISTS WHO CHANGED FILM (2019) THE LEGO MOVIE (2014) SUPERMANSION (2015-2019) THE ADVENTURES OF PUSS IN BOOTS (2015-2018) ROBOT CHICKEN (2010-2014) BIOGRAPHY Shawn Patterson is an Academy Award, Emmy and Grammy nominated Composer, Songwriter and Music Producer. Originally hailing from Athol, Massachusetts, Patterson's lifelong passion for music started with his late father, Ronald Patterson, a multi-instrumentalist musician. As a child, Shawn was exposed to television shows whose music scores (and sometimes songs) became engrained in his head: ‘Star Trek’, ‘The Six Million Dollar Man’, ‘Lost In Space’, and ‘Starsky & Hutch’. But it was his introduction to John Williams' legendary scores of ‘Star Wars’ and ‘Superman’ that initiated Patterson's profound life long journey to become a score composer and a part of cinematic storytelling through music. Shawn attended Berklee College of Music and the University of Massachusetts, Amherst; where he was selected to study privately and perform with legendary jazz musicians Dr. Billy Taylor and Max Roach. As a jazz, blues, rock guitarist and bandleader, Shawn played shows and lead various bands (including trio, duo and solo settings) while writing compositions in his free time. In 1987, Patterson attended and graduated from the Grove School of Music in Studio City, California. While attending Grove, Shawn studied orchestration and arranging privately with Roger Steinman. After relocating to Los Angeles in 1990, Patterson studied composition and orchestration privately with legendary Los Angeles Composer and Orchestrator, Jack Smalley. Patterson soon found success writing music for film trailers around town. Over the years, Shawn has composed score and written songs in an enormous wide range of styles for a number of award winning episodic television shows. -

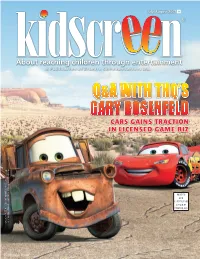

Q&A with Thq's Gary Rosenfeld

US$7.95 in the U.S. CA$8.95 in Canada US$9.95 outside of CanadaJuly/August & the U.S. 2007 1 ® Q&A WITH THQ’S GARY ROSENFELD CCARSARS GGAINSAINS TTRACTIONRACTION IINN LLICENSEDICENSED GGAMEAME BBIZIZ NUMBER 40050265 40050265 NUMBER ANADA USPS Approved Polywrap ANADA AFSM 100 CANADA POST AGREEMENT POST CANADA C IN PRINTED 001editcover_July_Aug07.indd1editcover_July_Aug07.indd 1 77/19/07/19/07 77:00:43:00:43 PMPM KKS.4562.Cartoon.inddS.4562.Cartoon.indd 2 77/20/07/20/07 55:06:05:06:05 PMPM KKS.4562.Cartoon.inddS.4562.Cartoon.indd 3 77/20/07/20/07 55:06:54:06:54 PMPM #8#+.#$.'019 9 9 Animation © Domo Production Committee. Domo © NHK-TYO 1998. [ZVijg^c\I]ZHiVg<^gah Star Girls and Planet Groove © Dianne Regan Sean Regan. XXXCJHUFOUUW K<C<M@J@FEJ8C<J19`^K\ek<ek\ikX`ed\ek%K\c%1)()$-'+$''-+\ok%)'(2\dX`c1iZfcc`ej7Y`^k\ek%km C@:<EJ@E>GIFDFK@FEJ19`^K\ek<ek\ikX`ed\ek%K\c%1)()$-'+$''-+\ok%)'-2\dX`c1idXippXe\b7Y`^k\ek%km KKS4548.BIGS4548.BIG TTENT.inddENT.indd 2 77/19/07/19/07 66:54:45:54:45 PMPM 1111 F3 to mine MMOG space for TV concepts 114Parthenon4 Kids: Geared up and ready to invest 1177 Will Backseat TV boost Nick’s in-car profile? 225Storm Hawks5 goes jjuly/augustuly/august viral with Guerilla 0077 HHighlightsighlights ffromrom tthishis iissuessue 10 up front 24 marketing France TV to invest in Chrysler and Nick hope more content and global to get more mileage out Special Reports web presence of the minivan set with 29 RADARSCREEN backseat TV feature Fred Seibert’s Frederator Films 13 ppd tries a fresh approach to Parthenon Kids offers 26 digital -

Q1 2021 Management's Discussion & Analysis

Share Information Investor Information Q At May 27, 2021, the Company All financial reports, news T HREE U had 32,024,314 common releases and corporate shares outstanding and stock information can be accessed on A M ONTHS options exercisable for our website at R E NDED 1,906,786 additional common www.wowunlimited.co shares and warrants T M ARCH 3 1 C o n t a c t Information 1 exercisable into 900,000 E 2 0 2 1 common shares. Investor Relations 200 – 2025 West Broadway R 2021 Vancouver, BC, Canada V6J 1Z6 [email protected] MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS This Management’s Discussion and Analysis (“MD&A”) is dated May 27, 2021 and is intended to assist in understanding the results of operations and financial condition of Wow Unlimited Media Inc. as at and for the three months ended March 31, 2021 and should be read in conjunction with the unaudited condensed interim consolidated financial statements and accompanying notes for the three months ended March 31, 2021 and other public disclosure documents of Wow Unlimited Media Inc., including its previously filed December 31, 2020, annual consolidated financial statements. Past performance may not be indicative of future performance. Unless otherwise noted, all amounts are reported in Canadian dollars, the Company’s functional currency, and have been prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (“IFRS”). Throughout the MD&A reference to “Wow Unlimited” or the “Company” refers to Wow Unlimited Media Inc. and its subsidiary entities. Additional information, including other publicly filed documents relating to the Company are available through the internet on the Canadian Securities Administrators’ System for Electronic Document Analysis and Retrieval (“SEDAR”), which can be accessed at www.sedar.com. -

Un Anno Di Zapping Guida Critica Family Friendly Ai Programmi Televisivi STAGIONE TELEVISIVA - 2015/2016

Osservatorio Media del Moige Movimento Italiano Genitori a cura di Elisabetta Scala Palmira Di Marco Francesco La Rosa un anno di zapping guida critica family friendly ai programmi televisivi STAGIONE TELEVISIVA - 2015/2016 prefazione di On. Antono Martusciello indice Prefazione 7 Marida Caterini Introduzione 9 Maria Rita Munizzi, Elisabetta Scala Legenda dei simboli 11 Schede di analisi critica dei programmi 13 Indice dei programmi 323 Glossario dei termini tecnici 335 Note professionali degli autori 337 5 prefazione Una stagione televisiva molto controversa punteggiata, troppo frequentemente, da imbarazzanti cadute di stile. Palinsesti costruiti per catturare la curiosità del pubbli- co facendo leva su istinti degradanti ma ritenuti forieri di audience e quindi appetibili agli investitori pubblicitari. La tv mostra un sensibile e progressivo deterioramento dei valori etici, meno attenta al rispetto per i telespettatori e, soprattutto, per i minori. Fortunatamente, uno spiraglio esiste. E la speranza che si possa invertire il trend, fidando in un piccolo schermo a misura di famiglia, diventa visibile come un faro nella nebbia. Un anno di zapping ha, da sempre, il compito di analiz- zare i palinsesti individuando i meriti e la qualità dei pro- grammi, delle fiction, degli spot pubblicitari, dei talk show, dell’informazione e dell’intrattenimento in tutti i settori. Un lavoro lungo un anno, mai fazioso, attento e gratifi- cante, pronto a indicare la strada giusta per un’inversio- ne di tendenza verso una tv propositiva per un pubblico trasversale. Un lavoro che conosco da vicino nel quale io stessa sono stata impegnata lo scorso anno. La famiglia è la maggior fruitrice del piccolo schermo sia nelle forma convenzionale, ancora in grado di riunire tut- ti dinanzi al vecchio caro elettrodomestico, sia nella sua evoluzione resa possibile dalle nuove tecnologie.