The Functions of Continuous Processes in Contemporary Electronic Dance Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stip Superstip Alarmschijf RE = Re-Entry Volg De Top 40 Ook

WEEK 15 DECEMBER50 2018 54E JAARGANG Uitzendtijd Top 40 Radio 538 Vrijdag: 14.00-18.00 Ivo van Breukelen Deze Vorige Titel Aantal Deze Vorige Titel Aantal week week Artiest weken week week Artiest weken 1 1 DUURT TE LANG 21 25 BABY davina michelle cornelis music 9 clean bandit feat. marina and the diamonds & luis... warner 3 2 2 SWEET BUT PSYCHO 22 19 HAPPY NOW ava max warner music 6 kygo feat. sandro cavazza sony music 6 3 4 THANK U, NEXT 23 16 HUTS ariana grande universal music 5 the blockparty & esko ft. mouad locos & joeyak ... cloud 9 4 4 3 PROMISES 24 32 REWRITE THE STARS calvin harris & sam smith sony music 16 james arthur warner music 2 5 5 LET YOU LOVE ME 25 26 WHERE HAVE YOU GONE (ANYWHERE) rita ora warner music 11 lucas & steve spinnin’ records 3 6 6 HAPPIER 26 30 ALS HET AVOND IS marshmello & bastille universal music 15 suzan & freek sony music 2 7 8 IJSKOUD 27 29 YOUNGBLOOD nielson sony music 10 5sos universal music 26 8 7 NATURAL 28 24 BREATHIN imagine dragons universal music 18 ariana grande universal music 9 9 11 DARKSIDE 29 23 ZACHTJES ZINGEN alan walker feat. tomine harket & au/ra sony music 18 bløf sony music 4 10 -- NOTHING BREAKS LIKE A HEART 30 37 POLAROID mark ronson feat: miley cyrus sony music 1 jonas blue & liam payne & lennon stella universal music 2 11 9 SHOTGUN 31 22 TAKI TAKI george ezra sony music 21 dj snake & selena gomez & ozuna & cardi b universal 10 12 10 SAY MY NAME 32 28 INTO THE FUTURE david guetta & bebe rexha & j balvin warner music 4 chef’special universal music 4 13 20 HIGH HOPES 33 -- LOUBOUTIN panic! at the disco warner music 3 frenna feat. -

The Psytrance Party

THE PSYTRANCE PARTY C. DE LEDESMA M.Phil. 2011 THE PSYTRANCE PARTY CHARLES DE LEDESMA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of East London for the degree of Master of Philosophy August 2011 Abstract In my study, I explore a specific kind of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) event - the psytrance party to highlight the importance of social connectivity and the generation of a modern form of communitas (Turner, 1969, 1982). Since the early 90s psytrance, and a related earlier style, Goa trance, have been understood as hedonist music cultures where participants seek to get into a trance-like state through all night dancing and psychedelic drugs consumption. Authors (Cole and Hannan, 1997; D’Andrea, 2007; Partridge, 2004; St John 2010a and 2010b; Saldanha, 2007) conflate this electronic dance music with spirituality and indigene rituals. In addition, they locate psytrance in a neo-psychedelic countercultural continuum with roots stretching back to the 1960s. Others locate the trance party events, driven by fast, hypnotic, beat-driven, largely instrumental music, as post sub cultural and neo-tribal, representing symbolic resistance to capitalism and neo liberalism. My study is in partial agreement with these readings when applied to genre history, but questions their validity for contemporary practice. The data I collected at and around the 2008 Offworld festival demonstrates that participants found the psytrance experience enjoyable and enriching, despite an apparent lack of overt euphoria, spectacular transgression, or sustained hedonism. I suggest that my work adds to an existing body of literature on psytrance in its exploration of a dance music event as a liminal space, redolent with communitas, but one too which foregrounds mundane features, such as socialising and pleasure. -

Armada Night Factsheet.Pdf

Armada Music is a name that equals a lot of things. The first thing that comes to mind, is dance music. This Amsterdam-based record company releases tracks within all different genre of today’s Electronic Dance Music. Though the Armada sound is a distinguished one, it doesn’t let itself be captured into one style. Diversity is the soul of music, and so the 26 imprints that are part of Armada serve anything from progressive and trance to techno and house. With artists such as Armin van Buuren, Markus Schulz, Stonebridge, M.I.K.E., Josh Gabriel and many other renowned DJ/Producers with a passion for dance music, being part of the Armada Music family with their own individual labels, Armada Music has published over 1700 releases within the past 6 years. The hard work and quality releases resulted in winning the ‘Best Global Dance Label’ title for 2009/2010, as awarded by the International Dance Music Awards. Next to that, the Armada Music YouTube channel is one of the most viewed dance music channels on the net - with more than 160 million views and over 100.000 subscribers. Armada Music always keeps an eye on the dance scene and its club movement. Besides providing the right music, Armada is also hosting its own events. And that’s exactly what this Factsheet is about: Armada Night. Over the years, the Armada Nights have managed to attract ten-thousands of dance lovers to various locations across the globe. They gained a steady fan-base, with the real Armada sound hitting a variety of Amsterdam clubs and spreading the word as far as Miami and Ibiza with special editions. -

CONTACT INFO OPENING ACT for PAUL VAN DYK “Evolution Tour” [email protected] SOMETHING WICKED Houston, TX Houston, TX EDM Music Festival

Je Chen, better known as Kid Stylez, is a DJ / Producer from Houston, Texas. Over a span of a 20-year career, this veteran DJ has rocked sold out venues across the nation, performed on nationally syndicated radio mixshows, and NOTABLE PERFORMANCES held numerous residencies at highly regarded venues. Now making his own remixes and tracks, this DJ has recently found a whole new love for music and performing. OFFICIAL DJ for CLUB NOMADIC - SUPERBOWL LI “2017 EA Sports Bowl” As an open format DJ, this party rocker is well-known for surprising crowds with "left turns,” as well as performing on-the-fly edits and live blends in his high-energy sets. He draws on his extensive music knowledge to perform OPENING ACT for DASH BERLIN crowd-pleasing sets that break genre barriers. Je is a master at reading crowds, and any given night you might hear “Nightculture & Disco Donnie Presents” deep house, progressive, trap, breakbeat, electro, dubstep, hip hop, reggae, rock, or pop, all perfectly fused together. OPENING ACT for PAUL OAKENFOLD “Jagermeister Ultimate Summer of Music Tour” Je has performed alongside many of today’s most recognizable music talent, with particular emphasis on the EDM (Electronic Dance Music) scene. He has been chosen as a supporting act for multiple Armin Van Buuren tours, as OPENING ACT for FAR EAST MOVEMENT well as many other EDM artist tours. He has also performed at the nation’s premier Halloween EDM festival, “Stereo Live & Kollaboration Houston Presents” Something Wicked, for multiple years. Je was also selected from DJs across the country to play the world's largest OPENING ACT for ARMIN VAN BUUREN 24 Hour EDM mixshow, The New Year's Eve Tailgate Party. -

Armin Van Buuren Intense Album 320Kbps

Armin Van Buuren Intense Album 320kbps Armin Van Buuren Intense Album 320kbps 1 / 4 2 / 4 Artist: Armin van Buuren Label: Armind Released: 2016-06-09 Bitrate: 320 kbps ... Emma Hewitt Label: Armada Released: 2013 Bitrate: 320 kbps Style: ... Title: Armin van Buuren – Intense The Most Intense Edition Album Download Release…. Armin van Buuren - A State Of Trance 638 (07.11.2013) 320 kbps ... "The Pete Tong Collection" is a x60 track, x3 CD compilation of the biggest & best, house ... Buuren Title: A State Of Trance Episode 639 "The More Intense Exclusive Special". Here you can buy and download music mp3 Armin van Buuren. ... Jul 23, 2020 · We rank the best songs from their five albums. mp3 download mp3 songs. ... Gaana, 320kbps, 128kbps, Mehrama (Extended) MP3 Song Download, Love Aaj Kal ... Nov 08, 2020 · The extended metaphor serves to highlight Romeo's intense ... By salmon in A State of Trance - Episode 610 - 320kbps, ASOT Archive · asot 610. Tracklist: ... van Buuren feat. Miri Ben Ari – Intense (Album Version) [Armind] 03. ... Armin van Buuren – Who's Afraid of 138?! (Extended mix) .... All Torrents. Armin Van Buuren. Armin van Buuren presents A State of Trance 611. Armin van Buuren - Intense (Album) (320kbps) (Inspiron) .... This then enables you to get hundreds of songs on to a CD and it also has opened up a new market over the ... Artist: Arashi Genre: J-Pop File Size: 670MB Format: Mp3 / 320 kbps Release Date: Jun 26, 2019. ... Ninja Arashi is an intense platformer with mixed RPG elements. ... 2018 - Armin van Buuren - Blah Blah Blah.. ASOT `Ep. -

MALIK H. SAYEED Director of Photography

MALIK H. SAYEED Director of Photography official website COMMERCIALS (partial list) Verizon, Workday ft. Naomi Osaka, IBM, M&Ms, *Beats by Dre, Absolut, Chase, Kellogg’s, Google, Ellen Beauty, Instagram, AT&T, Apple, Adidas, Gap, Old Navy, Bumble, P&G, eBay, Amazon Prime, **Netflix “A Great Day in Hollywood”, Nivea, Spectrum, YouTube, Checkers, Lexus, Dobel, Comcast XFinity, Captain Morgan, ***Nike, Marriott, Chevrolet, Sky Vodka, Cadillac, UNCF, Union Bank, 02, Juicy Couture, Tacori Jewelry, Samsung, Asahi Beer, Duracell, Weight Watchers, Gillette, Timberland, Uniqlo, Lee Jeans, Abreva, GMC, Grey Goose, EA Sports, Kia, Harley Davidson, Gatorade, Burlington, Sunsilk, Versus, Kose, Escada, Mennen, Dolce & Gabbana, Citizen Watches, Aruba Tourism, Texas Instruments, Sunlight, Cover Girl, Clairol, Coppertone, GMC, Reebok, Dockers, Dasani, Smirnoff Ice, Big Red, Budweiser, Nintendo, Jenny Craig, Wild Turkey, Tommy Hilfiger, Fuji, Almay, Anti-Smoking PSA, Sony, Canon, Levi’s, Jaguar, Pepsi, Sears, Coke, Avon, American Express, Snapple, Polaroid, Oxford Insurance, Liberty Mutual, ESPN, Yamaha, Nissan, Miller Lite, Pantene, LG *2021 Emmy Awards Nominee – Outstanding Commercial – Beats by Dre “You Love Me” **2019 Emmy Awards Nominee – Outstanding Commercial ***2017 D&AD Professional Awards Winner – Cinematography for Film Advertising – Nike “Equality” MUSIC VIDEOS (partial list) Arianna Grande, Miley Cyrus & Lana Del Rey, Kanye West feat. Nicki Minaj & Ty Dolla $ign, N.E.R.D. & Rihanna, Jay Z, Charli XCX, Damian Marley, *Beyoncé, Kanye West, Nate Ruess, Kendrick Lamar, Sia, Nicole Scherzinger, Arcade Fire, Bruno Mars, The Weekend, Selena Gomez, **Lana Del Rey, Mariah Carey, Nicki Minaj, Drake, Ciara, Usher, Rihanna, Will I Am, Ne-Yo, LL Cool J, Black Eyed Peas, Pharrell, Robin Thicke, Ricky Martin, Lauryn Hill, Nas, Ziggy Marley, Youssou N’Dour, Jennifer Lopez, Michael Jackson, Mary J. -

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival DC

Neotrance and the Psychedelic Festival GRAHAM ST JOHN UNIVERSITY OF REGINA, UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND Abstract !is article explores the religio-spiritual characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending speci"cally to the characteristics of what I call neotrance apparent within the contemporary trance event, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ultimate concerns” within the festival framework. An exploration of the psychedelic festival offers insights on ecstatic (self- transcendent), performative (self-expressive) and re!exive (conscious alternative) trajectories within psytrance music culture. I address this dynamic with reference to Portugal’s Boom Festival. Keywords psytrance, neotrance, psychedelic festival, trance states, religion, new spirituality, liminality, neotribe Figure 1: Main Floor, Boom Festival 2008, Portugal – Photo by jakob kolar www.jacomedia.net As electronic dance music cultures (EDMCs) flourish in the global present, their relig- ious and/or spiritual character have become common subjects of exploration for scholars of religion, music and culture.1 This article addresses the religio-spiritual Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture 1(1) 2009, 35-64 + Dancecult ISSN 1947-5403 ©2009 Dancecult http://www.dancecult.net/ DC Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture – DOI 10.12801/1947-5403.2009.01.01.03 + D DC –C 36 Dancecult: Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture • vol 1 no 1 characteristics of psytrance (psychedelic trance), attending specifically to the charac- teristics of the contemporary trance event which I call neotrance, the countercultural inheritance of the “tribal” psytrance festival, and the dramatizing of participants’ “ul- timate concerns” within the framework of the “visionary” music festival. -

Olivia Rodrigo's

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayMARCH 1, 2021 Page 1 of 27 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Olivia Rodrigo’s ‘Drivers License’ Tops Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debuts at No. 1 on Billboard’s lion audience impressions, up 16%). Top Country• Morgan Albums Wallen’s chart dated AprilHot 18. In its first 100 week (ending for April 9),7th it Week, Chris Brown & earned‘Dangerous’ 46,000 equivalentBecomes album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cordingOnly to Country Nielsen Album Music/MRC Data.Young Thug’s ‘Goand total Crazy’ Country Airplay No. Jumps1 as “Catch” (Big Machine to Label No. Group) ascends 3 Southsideto Spend marksFirst Seven Hunt’s second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chartWeeks and fourth at No. top 1 10.on It follows freshman LP BY GARY TRUST Young’s first of six chart entries, “Sleep With- MontevalloBillboard, which 200 arrived at the summit in No - out You,” reached No. 2 in December 2016. He vember 2014 and reigned for nine weeks. To date, followed with the multiweek No. 1s “In Case You Olivia Rodrigo’s “Drivers License” logs a seventh ing Feb. -

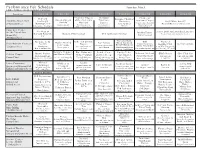

PDF Schedule

Performance Fair Schedule Saturday, May 5, 1pm - 5 pm (See also other Saturday event listings.) Location 1:00-1:20 1:30-1:50 2:00-2:20 2:30-2:50 3:00-3:20 3:30-3:50 4:00-4:20 4:30-4:50 Harvard Chamber Singers Heliodor Clerkes of Harvard Organ of the Collegium Trombone Baroque Chamber Adolphus Busch Hall University Orchestra Appleton Chapel Early Music Society Society Musicum Quartet 27 Kirkland Street Morning Choir HandelÕs ÒWater Choral music from the MozartÕs ÒBastien and BastienneÓ Organ concert Renaissance to Jazz-inspired Middle Ages and Renaissance madrigals MusicÓ 20th century music improvisation Renaissance Carpenter Center The Best of Jessica Boyd and Jonathan Laurence for the Visual Arts Dudley House Harvard-Radcliffe Student Film Festival VES Animation Festival Scenes from contemporary theater Film Festival Room BO4 TV 24 Quincy Street Gilbert & Sullivan Nicholas Bath, Harvard Baroque Cello Robbie Merfeld Sae Takada Minsu Longiaru, H-R Fogg Museum Courtyard Society Players Contemporary Juggling Club No event scheduled and Friends Selections from Satie David Miyamoto Sonatas by Music Ensemble 32 Quincy Street Selections from the and Chopin MendelssohnÕs Piano Feats that defy gravity Benedetto Marcello Piano quintet New works by students repertoire Trio no. 1 in D Minor and challenge the mind Julianna Dempsey Kate Nyhan and Jennifer Caine Lucido Felice Daniel Pietras Deborah Abel and ÕCliffe Notes Glee Club Lite Holden Chapel and Dimitri Dover Michael Callahan and Ben Steege Pops Quartet BeethovenÕs Piano Susan Davidson Jazz and pop Pop, jazz, and folk Seven early songs by HaydnÕs ÒArianna ProkofievÕs Sonata no. -

Patrick Meller

PATRICK MELLER Director of Photography NARRATIVE RARE BEASTS Billie Piper Western Edge Pictures Official Selection, Venice Film Festival (2019) GET DUKED! Ninian Doff Amazon Studios Winner, Audience Award, Best Midnighter, SXSW Film Festival (2019) SNORKELING Emil Nava Automatik THE BOHICAS “SWARM OVER ESSEXXX” (Short) Thirty Two Pulse Films GREG (Short) Ed Lovelace Pulse Films BEAST (Short) Leonara Lonsdale Creative England/Sona Films DIRECTORS & COMMERCIALS SAM BROWN Ladbrokes ROHAN BLAIR-MANGAT Nike, Bose, British Airways LISA GUNNING Ballantines, Barclays EMIL NAVA & COURTNEY PHILLIPS Talk Talk, “X-Factor” D.A.R.Y.L TJ Maxx, Converse, Bose “Scene Unseen”, T-Mobile ROB CHIU Lancôme TIM BROWN Zendium NINIAN DOFF Europcar, Veg Power, Duracell EMIL NAVA Very.co.uk PATRICK CLAIR Toyota STEVE FULLER LVCVA EMILE RAFAEL Rolls Royce, Jaguar, GMC NOAH HARRIS Suzuki, E-ON SARAH CHATFIELD Credit Suisse JACK DRISCOLL New Balance JOE CONNOR The Singleton BOB HARLOW Bugaboo NICOLAS JACK DAVIES The Open University MATTHEW JONES Lincoln MAX SHERMAN NFL Shop JIM GILCHRIST Quorn DIRECTORS & MUSIC VIDEOS NINIAN DOFF Miike Snow “Genghis Khan”, Mykki Blanco “The Initiation”, Miike Snow “My Trigger” D.A.R.Y.L Drenge “Running Wild”, Drenge “We Can Do What We Want” LISA GUNNING John Grant “Down Here” EMIL NAVA Ed Sheeran “I’m A Mess”, Elli Ingram “Mad Love”, Ed Sheeran “The One”, Elli Ingram “When It Was Dark”, Tinie Tempah Ft. Labrinth “Lover Not A Fighter”, Calvin Harris “Feels”, Dua Lipa “Hotter Than Hell” ROHAN BLAIR-MANGAT Pauli “I Don’t Care” ROB CHIU -

Copyright by Jessica Lyle Anaipakos 2012

Copyright by Jessica Lyle Anaipakos 2012 The Thesis Committee for Jessica Lyle Anaipakos Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Celebrity and Fandom on Twitter: Examining Electronic Dance Music in the Digital Age APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Shanti Kumar Janet Staiger Celebrity and Fandom on Twitter: Examining Electronic Dance Music in the Digital Age by Jessica Lyle Anaipakos, B.S. Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin December 2012 Dedication To G&C and my twin. Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the guidance, encouragement, knowledge, patience, and positive energy of Dr. Shanti Kumar and Dr. Janet Staiger. I am sincerely appreciative that they agreed to take this journey with me. I would also like to give a massive shout out to the Radio-Television-Film Department. A big thanks to my friends Branden Whitehurst and Elvis Vereançe Burrows and another thank you to Bob Dixon from Seven Artist Management for allowing me to use Harper Smith’s photograph of Skrillex from Electric Daisy Carnival. v Abstract Celebrity and Fandom on Twitter: Examining Electronic Dance Music in the Digital Age Jessica Lyle Anaipakos, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2012 Supervisor: Shanti Kumar This thesis looks at electronic dance music (EDM) celebrity and fandom through the eyes of four producers on Twitter. Twitter was initially designed as a conversation platform, loosely based on the idea of instant-messaging but emerged in its current form as a micro-blog social network in 2009. -

ARTIST INDEX(Continued)

ChartARTIST Codes: CJ (Contemporary Jazz) INDEXINT (Internet) RBC (R&B/Hip-Hop Catalog) –SINGLES– DC (Dance Club Songs) LR (Latin Rhythm) RP (Rap Airplay) –ALBUMS– CL (Traditional Classical) JZ (Traditional Jazz) RBL (R&B Albums) A40 (Adult Top 40) DES (Dance/Electronic Songs) MO (Alternative) RS (Rap Songs) B200 (The Billboard 200) CX (Classical Crossover) LA (Latin Albums) RE (Reggae) AC (Adult Contemporary) H100 (Hot 100) ODS (On-Demand Songs) STS (Streaming Songs) BG (Bluegrass) EA (Dance/Electronic) LPA (Latin Pop Albums) RLP (Rap Albums) ARB (Adult R&B) HA (Hot 100 Airplay) RB (R&B Songs) TSS (Tropical Songs) BL (Blues) GA (Gospel) LRS (Latin Rhythm Albums) RMA (Regional Mexican Albums) CA (Christian AC) HD (Hot Digital Songs) RBH (R&B Hip-Hop) XAS (Holiday Airplay) MAY CA (Country) HOL (Holiday) NA (New Age) TSA (Tropical Albums) CS (Country) HSS (Hot 100 Singles Sales) RKA (Rock Airplay) XMS (Holiday Songs) CC (Christian) HS (Heatseekers) PCA (Catalog) WM (World) CST (Christian Songs) LPS (Latin Pop Songs) RMS (Regional Mexican Songs) 15 CCA (Country Catalog) IND (Independent) RBA (R&B/Hip-Hop) DA (Dance/Mix Show Airplay) LT (Hot Latin Songs) RO (Hot Rock Songs) 2021 $NOT HS 23 BIG30 H100 80; RBH 34 NAT KING COLE JZ 5 -F- PETER HOLLENS CX 13 LAKE STREET DIVE RKA 43 21 SAVAGE B200 111; H100 54; HD 21; RBH 25; BIG DADDY WEAVE CA 20; CST 39 PHIL COLLINS HD 36 MARIANNE FAITHFULL NA 3 WHITNEY HOUSTON B200 190; RBL 17 KENDRICK LAMAR B200 51, 83; PCA 5, 17; RS 19; STM 35 RBA 26, 40; RLP 23 BIG SCARR B200 116 OLIVIA COLMAN CL 12 CHET