The Y-Works Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Florida Historical Quarterly

COVER The Gainesville Graded and High School, completed in 1900, contained twelve classrooms, a principal’s office, and an auditorium. Located on East University Avenue, it was later named in honor of Confederate General Edmund Kirby Smith. Photograph from the postcard collection of Dr. Mark V. Barrow, Gainesville. The Historical Quarterly Volume LXVIII, Number April 1990 THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY COPYRIGHT 1990 by the Florida Historical Society, Tampa, Florida. The Florida Historical Quarterly (ISSN 0015-4113) is published quarterly by the Florida Historical Society, Uni- versity of South Florida, Tampa, FL 33620, and is printed by E. O. Painter Printing Co., DeLeon Springs, Florida. Second-class postage paid at Tampa and DeLeon Springs, Florida. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the Florida Historical Society, P. O. Box 290197, Tampa, FL 33687. THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY Samuel Proctor, Editor Everett W. Caudle, Editorial Assistant EDITORIAL. ADVISORY BOARD David R. Colburn University of Florida Herbert J. Doherty University of Florida Michael V. Gannon University of Florida John K. Mahon University of Florida (Emeritus) Jerrell H. Shofner University of Central Florida Charlton W. Tebeau University of Miami (Emeritus) Correspondence concerning contributions, books for review, and all editorial matters should be addressed to the Editor, Florida Historical Quarterly, Box 14045, University Station, Gainesville, Florida 32604-2045. The Quarterly is interested in articles and documents pertaining to the history of Florida. Sources, style, footnote form, original- ity of material and interpretation, clarity of thought, and in- terest of readers are considered. All copy, including footnotes, should be double-spaced. Footnotes are to be numbered con- secutively in the text and assembled at the end of the article. -

The Florida Election Campaign Financing Act: a Bold Approach to Public Financing of Elections

Florida State University Law Review Volume 14 Issue 3 Article 9 Fall 1986 The Florida Election Campaign Financing Act: A Bold Approach to Public Financing of Elections Chris Haughee Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Legislation Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Chris Haughee, The Florida Election Campaign Financing Act: A Bold Approach to Public Financing of Elections, 14 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. 585 (1986) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol14/iss3/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FLORIDA ELECTION CAMPAIGN FINANCING ACT: A BOLD APPROACH TO PUBLIC FINANCING OF ELECTIONS CHRIS HAUGHEE* Florida's explosive population growth and the changing ways of life in this urban state have created problems in the political process just as troubling as the substantive problems of the envi- ronment, social services, and criminal justice. After all, these substantive issues can only be addressed by consensus solutions if the political process itself has integrity. In this Article, the author reviews the history of modern campaign reforms in Flor- ida and other jurisdictions, then examines the new system for public financing of statewide elections in Florida. He concludes that, despite the good intentions of the legislature, the utimate success or failure of the program will depend upon its accept- ance by all players in the electoral process. -

The New South Gubernatorial Campaigns of 1970 and the Changing Politics of Race

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1998 The ewN South Gubernatorial Campaigns of 1970 and the Changing Politics of Race. Donald Randy Sanders Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Sanders, Donald Randy, "The eN w South Gubernatorial Campaigns of 1970 and the Changing Politics of Race." (1998). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6760. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6760 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

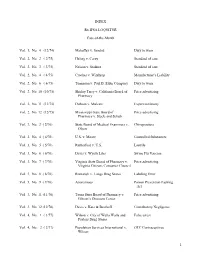

INDEX Rx IPSA LOQUITUR Case-Of-The-Month Vol. 1, No. 4

INDEX Rx IPSA LOQUITUR Case-of-the-Month Vol. 1, No. 4 (12/74) Mahaffey v. Sandoz Duty to warn Vol. 2, No. 2 ( 2/75) Heling v. Carey Standard of care Vol. 2, No. 3 ( 3/75) Nelson v. Stadner Standard of care Vol. 2, No. 4 ( 4/75) Crocker v. Winthrop Manufacturer’s Liability Vol. 2, No. 6 ( 6/75) Tonneson v. Paul B. Elder Company Duty to warn Vol. 2, No. 10 (10/75) Shirley Terry v. California Board of Price advertising Pharmacy Vol. 2, No. 11 (11/75) Dobson v. Mulcare Expert testimony Vol. 2, No. 12 (12/75) Mississippi State Board of Price advertising Pharmacy v. Steele and Schub Vol. 3, No. 2 ( 2/76) State Board of Medical Examiners v. Chiropractors Olson Vol. 3, No. 4 ( 4/76) U.S. v. Moore Controlled Substances Vol. 3, No. 5 ( 5/76) Rutherford v. U.S. Laetrile Vol. 3, No. 6 ( 6/76) Davis v. Wyeth Labs Swine Flu Vaccine Vol. 3, No. 7 ( 7/76) Virginia State Board of Pharmacy v. Price advertising Virginia Citizens Consumer Council Vol. 3, No. 8 ( 8/76) Romanyk v. Longs Drug Stores Labeling Error Vol. 3, No. 9 ( 9/76) Anonymous Poison Prevention Packing Act Vol. 3, No. 11 (11/76) Texas State Board of Pharmacy v. Price advertising Gibson’s Discount Center Vol. 3, No. 12 (12/76) Davis v. Katz & Besthoff Contributory Negligence Vol. 4, No. 1 ( 1/77) Wilson v. City of Walla Walla and False arrest Payless Drug Stores Vol. 4, No. 2 ( 2/77) Population Services International v. -

Harry S. Dent Papers Mss.0158

Harry S. Dent Papers Mss.0158 Clemson University Libraries Special Collections Harry S. Dent Papers Mss.0158 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY INFORMATION Summary Information Repository Clemson University Libraries Special Collections Biographical Note Creator - Correspondent Scope and Content Note Agnew, Spiro T., 1918-1996 Arrangement note Creator - Correspondent Administrative Information Barton, Bill Controlled Access Headings Creator - Correspondent Collection Inventory BeLieu, Kenneth E., (Kenneth Eugene), 1914-2001 White House Files Series Creator - Correspondent Personal Series Brownell, Gordon Legal Series Creator - Correspondent Laity: Alive and Serving Bush, George, 1924- Series Creator - Correspondent Books Series Butterfield, Alexander Porter, 1926- Scrapbooks Series Creator - Correspondent Photographs Series Campbell, Carroll A. Oversize Series Creator - Correspondent Audio-Visual Series Chapin, Dwight L., (Dwight Lee), 1940- Memorabilia Series Creator - Correspondent Colson, Charles W. Creator - Correspondent Dent, Betty Creator - Creator Dent, Harry S. , 1930-2007 Creator - Correspondent Duffy, James Evan, 1932- Creator - Correspondent file:///C/Users/jredd/Desktop/Mss0158Dent.html[4/19/2019 1:39:37 PM] Harry S. Dent Papers Mss.0158 Eckerd, Jack M., 1913- Creator - Correspondent Edwards, James B., 1927- Creator - Correspondent Ehrlichman, John Creator - Correspondent Flanigan, Peter M., (Peter Magnus), 1923- Creator - Correspondent Ford, Gerald R., 1913-2006 Creator - Correspondent Ford, Leighton Creator - Correspondent Goldwater, -

![10/1/78 President's Trip to Florida [Briefing Book]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1607/10-1-78-presidents-trip-to-florida-briefing-book-3101607.webp)

10/1/78 President's Trip to Florida [Briefing Book]

10/01/78 President’s Trip to Florida [Briefing Book] Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: Presidential Files; Folder: 10/01/78 President’s Trip to Florida [Briefing Book]; Container 93 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf WITHDRAWAL SHEET (PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARIES) CORRESPONDENTS OR TITLE DATE RESTRICTION Page from briefit.lg book on Pres:ident Carter 1 s trip to F ler ida 1 1 pg . , re :Personal comments 1 0 I 1 I 1·a c &· I. f I !I, FILE LOCATION Carter Presidential Papers-Staff 6ffic~s, Offic~ of Staff Se.-Pres. Handwriting File, President 1 s Trip: to FL 10/1178 .[Brie:fing Book] RESTRICTION CODES (A) Closed by Executive Order 12356'governing access to national secu6ty information. (B) Closed by statute or by the agency which originated the document. (C) Closed in accordance with restrictions contained in the donor's deed of gift . NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMIN'ISTRATION. NA FORM 1429 (6-85) TABLE OF CONTENTS I. SCHEDULE - Summary Schedule Maps - Diagrams II. ISSUES - Political Overview - Congressional Delegation - General Issues III. CAPE CANAVERAL - Map - Issues - NASA - Events Space Center Tour Space Medals of Honor Awards IV. DISNEY WORLD - Orlando - Disney World - Event Address to the International Chamber of Commerce ,;' \ \ SCHEDULE J ~ .. \ ) SUMMARY SCHEDUL1 THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON SUMMARY SCHEDULE TRIP TO FLORIDA SUNDAY - OCTOBER 1, 1978 12:15 p.m. Depart South Grounds via helicopter for Andrews AFB. 12 :.35 p.m.• Air Force One departs Andrews for Kennedy Space Center, Florida. (Flying Time: 1 hr. 55 min~.) 2:30 p.m. -

Republican Candidate Taping Sessions, 1974” of the Robert T

The original documents are located in Box 27, folder “Republican Candidate Taping Sessions, 1974” of the Robert T. Hartmann Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 27 of the Robert T. Hartmann Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library .- THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON October 10, 1974 TAPING SESSIONS FOR REPUBLICAN CANDIDATES 11:30 a.m.- 12:55 p.m. (85 minutes) October 12, 1974 (Saturday) Cabinet Room & Private Office From: Gwen Anderson Q Via: Dean Burch ~ I. PURPOSE A. Film and radio endorsement tape session for Michigan 5th District Republican Congressional candidate Paul G. Goebel, Jr. B. Taping session to cut radio tape endorsements for campaign use of Republican candidates. I I. BACKGROUND A. Filmed endorsement for Paul G. Goebel, Jr. 1. President has agreed to make filmed endorsement for candidate Paul G. Goebel, Jr. 2. National Republican Congressional Committee will arrange for appropriate film and taping equipment and crew. -

Sunland Tribune

Sunland Tribune Volume 21 Article 1 1995 Full Issue Sunland Tribune Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/sunlandtribune Recommended Citation Tribune, Sunland (1995) "Full Issue," Sunland Tribune: Vol. 21 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/sunlandtribune/vol21/iss1/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sunland Tribune by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Table of Contents THE PRESIDENT’S REPORT By Charles A. Brown, President, Tampa Historical Society 1 JOHN T. LESLEY: Tampa’s Pioneer Renaissance Man By Donald J. Ivey 3 SIN CITY, MOONSHINE WHISKEY AND DIVORCE By Pamela N. Gibson 21 COLONEL SAM REID: The Founding of the Manatee Colony and Surveying the Manatee Country, 1841-1847 By Joe Knetsch 29 THE CIRCUIT RIDING PREACHERS: They Sowed the Seed SUNLAND By Norma Goolsby Frazier 35 TRIBUNE DAVID LEVY YULEE: Florida’s First U. S. Senator By Hampton Dunn 43 Volume XXI November, 1995 “HOT, COLD, WHISKEY PUNCH”: The Civil War Letters of Journal of the Charles H. Tillinghast, U. S. N. TAMPA HISTORICAL SOCIETY By David J. Coles and Richard J. Ferry 49 Tampa, Florida THE OAKLAWN CEMETERY RAMBLE – 1995 KYLE VanLANDINGHAM By Arsenio M. Sanchez 65 Editor in Chief 1995 D. B. McKAY AWARD WINNER: Preservationist Stephanie Ferrell 1995 Officers By Hampton Dunn 67 CHARLES A. BROWN MEET THE AUTHORS 70 President 1995 SUNLAND TRIBUNE PATRONS 71 KYLE S. VanLANDINGHAM Vice President TAMPA HISTORICAL SOCIETY MEMBERSHIP ROSTER – October 12, 1995 73 MARY J. -

June 24, 1975 Washington, D

Scanned from the President's Daily Diary Collection (Box 76) at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS SERVICE WITHD RAWAL SHEET (PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARIES) FORM OF CORRESPONDENTS OR TITLE DATE RESTRICTION DOCUMENT 1-{~ ApprlndiX B , tc/al-f/75 C (~-red Co£>:J qVa.;{ab/~ I" ~V) file.') RESTRICTION COOES (AI CIOSEld by Executive Order 12356 govorning access to national security information. (B) Closed by statute or by tho agency which origlnaled the document. eel Closed in accordance wilh restrictions contained in the donor's deed of gift , GSA FO~M 7122 (REV. 5-32) THE WHITE HOUSE THE DAILY DIARY OF PRESIDENT GERALD R. FORD PLACE DAY BEGAN DATE (Mo., Day, Yr.) THE WHITE HOUSE JUNE 24 1975 WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME DAY 6:55 a.m. TUESDAY TIME "3ai "~u ACTIVITY 0: ~ 1------,.----1 II II In Oul c.. ~ 6:55 The President had breakfast. 7:35 The President went to the Oval Office. The President met with: 7:40 7:55 David A. Peterson, Chief, Central Intelligence Agency/Office of Current Intelligence (CIA/OCI) White House Support Staff 7:40 8:00 Lt. Gen. Brent Scowcroft, Deputy;. Assistant for National Security Affairs 8:05 8:25 The President met with his Counsellor, Robert T. Hartmann. The President met with: 8:30 9:15 Donald H. Rumsfeld, Assistant 9:05 9:15 Rogers C.B. Morton, Secretary of Commerce 9:15 9:28 The President met with his Counsellor, John O. Marsh, Jr. 9:30 P The President telephoned Director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and Assistant for Management and Budget James T. -

Journal of the Senate

Journal of the Senate Number 22—Regular Session Wednesday, March 20, 2002 CONTENTS DOCTOR OF THE DAY Bills on Third Reading . 1037 The President recognized Dr. Robert Knaus of Seminole, sponsored by Call to Order . 1036, 1110 Senator King, as doctor of the day. Dr. Knaus specializes in Psychology Co-Sponsors . 1222 and Sports Medicine. House Messages, Final Action . 1222 House Messages, First Reading . 1212 ADOPTION OF RESOLUTIONS Introduction and Reference of Bills . 1212 Motions . 1110, 1212 At the request of Senator Dawson— Motions Relating to Committee Reference . 1212 Point of Order . 1197, 1204 By Senator Dawson— Point of Order Ruling . 1205 Remarks . 1111, 1178 SR 1896—A resolution in honor of the late Charles Spencer Pompey. Reports of Committees . 1212 Resolutions . 1036 WHEREAS, on July 24, 2001, the Delray Beach area lost a valued Special Order Calendar . 1061, 1110, 1130 citizen and friend in the person of longtime educator, historian, and Special Recognition . 1111, 1116 activist Charles Spencer Pompey, only seven days short of his eighty- Statement of Intent . 1042 sixth birthday, and CALL TO ORDER WHEREAS, encouraged by his mother’s determination that her five children be properly educated, Charles Pompey became valedictorian of The Senate was called to order by President McKay at 9:00 a.m. A his high school class at the age of 15 and graduated summa cum laude quorum present—39: in 1939 from Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte, North Carolina, at that time a remarkable achievement for an African American, and Mr. President Geller Posey Brown-Waite Holzendorf Pruitt WHEREAS, during a career that spanned 41 years, Mr. -

The Current State of Marcia. P. Hoffman School of the Arts

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Arts Administration Master's Reports Arts Administration Program 8-2014 Thriving or Surviving: The Current State of Marcia. P. Hoffman School of the Arts Emily Fredrickson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/aa_rpts Part of the Arts Management Commons Recommended Citation Fredrickson, Emily, "Thriving or Surviving: The Current State of Marcia. P. Hoffman School of the Arts" (2014). Arts Administration Master's Reports. 165. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/aa_rpts/165 This Master's Report is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Master's Report in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Master's Report has been accepted for inclusion in Arts Administration Master's Reports by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thriving or Surviving: The Current State of Marcia. P. Hoffman School of the Arts An Internship Report Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Arts Administration By Emily Fredrickson Florida State University, 2012 August 2014 Table of Contents ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................................iii Chapter 1: Profile of the Arts Organization................................................................................... -

Press Secretary Briefings, 10/21/75

Digitized from Box 13 of the Ron Nessen Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library This Copy For______________ __ N E W S C 0 N F E R E N C E #352 AT ThL WHITE HOUSE WITH JACK HUSHEN AT 9:20 A.M. EDT OCTOBER 21, 1975 TUESDAY MR. HUSHEN: Dr. LukashI reported that the President slept soundly all night long; awoke at about 7:20a.m. Dr. Lukash examined him at that time and found that his temperature had dropped into the 99 range. Q What is the 99 range? MR. HUSHEN: Less than 100. (Laughter) Q More than 99. Q Below normal and ailing? MR. HUSHEN: Upon initial examination, the President's general physical findings appear to be improved. Q Could you repeat that? MR. HUSHEN: The President's general physical findings appear to be improved. Q That means he has generally improved? MR. HUSHEN: Correct. I was just giving you Dr. Lukash's terminology. Dr. Lukash said the treatment program will continue, which is restricted activity, bed rest and medication. The President had his regular breakfast at about 8:30 consisting of orange juice, melon, English muffin and tea. That is all I have to give you. 0 What about his schedule? Are all these meetings cancelled that Ron had said last night? MORE #352 , . -=-, - 2 - #352-10/21 MR. HUSHEN: Yes. Q He will have maybe a few aides in like yesterday? MR. HUSHEN: Don Rumsfeld is going over to meet with him right now. Q Who is? MR. HUSHEN: Don Rumsfeld.