Criminalization of Search-And-Rescue Operations in the Mediterranean Has Been Accompanied by Rising Migrant Death Rate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

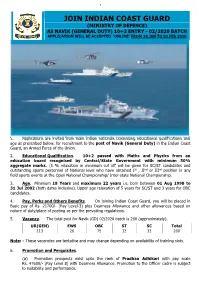

"Online" Application the Candidates Need to Logon to the Website and Click Opportunity Button and Proceed As Given Below

1 JOIN INDIAN COAST GUARD (MINISTRY OF DEFENCE) AS NAVIK (GENERAL DUTY) 10+2 ENTRY - 02/2020 BATCH APPLICATION WILL BE ACCEPTED ‘ONLINE’ FROM 26 JAN TO 02 FEB 2020 1. Applications are invited from male Indian nationals possessing educational qualifications and age as prescribed below, for recruitment to the post of Navik (General Duty) in the Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union. 2. Educational Qualification. 10+2 passed with Maths and Physics from an education board recognised by Central/State Government with minimum 50% aggregate marks. (5 % relaxation in minimum cut off will be given for SC/ST candidates and outstanding sports personnel of National level who have obtained Ist , IInd or IIIrd position in any field sports events at the Open National Championship/ Inter-state National Championship. 3. Age. Minimum 18 Years and maximum 22 years i.e. born between 01 Aug 1998 to 31 Jul 2002 (both dates inclusive). Upper age relaxation of 5 years for SC/ST and 3 years for OBC candidates. 4. Pay, Perks and Others Benefits. On joining Indian Coast Guard, you will be placed in Basic pay of Rs. 21700/- (Pay Level-3) plus Dearness Allowance and other allowances based on nature of duty/place of posting as per the prevailing regulations. 5. Vacancy. The total post for Navik (GD) 02/2020 batch is 260 (approximately). UR(GEN) EWS OBC ST SC Total 113 26 75 13 33 260 Note: - These vacancies are tentative and may change depending on availability of training slots. 6. Promotion and Perquisites. (a) Promotion prospects exist upto the rank of Pradhan Adhikari with pay scale Rs. -

(Mkc) Current Awareness Bulletin June 2019

INTERNATIONAL MARITIME ORGANIZATION MARITIME KNOWLEDGE CENTRE (MKC) “Sharing Maritime Knowledge” CURRENT AWARENESS BULLETIN JUNE 2019 www.imo.org Maritime Knowledge Centre (MKC) [email protected] www d Maritime Knowledge Centre (MKC) About the MKC Current Awareness Bulletin (CAB) The aim of the MKC Current Awareness Bulletin (CAB) is to provide a digest of news and publications focusing on key subjects and themes related to the work of IMO. Each CAB issue presents headlines from the previous month. For copyright reasons, the Current Awareness Bulletin (CAB) contains brief excerpts only. Links to the complete articles or abstracts on publishers' sites are included, although access may require payment or subscription. The MKC Current Awareness Bulletin is disseminated monthly and issues from the current and the past years are free to download from this page. Email us if you would like to receive email notification when the most recent Current Awareness Bulletin is available to be downloaded. The Current Awareness Bulletin (CAB) is published by the Maritime Knowledge Centre and is not an official IMO publication. Inclusion does not imply any endorsement by IMO. Table of Contents IMO NEWS & EVENTS ............................................................................................................................ 2 UNITED NATIONS ................................................................................................................................... 4 CASUALTIES........................................................................................................................................... -

Mare Nostrum Project

Mare Nostrum Project Final Report: Legal-Institutional Instruments for Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) in the Mediterranean 2016 Bridging the Legal-Institutional Gap in Mediterranean Coastline Management MARE NOSTRUM PROJECT: Bridging the Legal- Institutional Gap in Mediterranean Coastline Management Final Report: Legal -Institutional Instruments for Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) in the Mediterranean Project Head: Rachelle Alterman Writing Team: Cygal Pellach and Dafna Carmon Additional Contributors: Na'ama Teschner Raanan Boral Mare Nostrum Project ENPI CBC MSB Grant Agreement I-A/1.3/093 MARE NOSTRUM marenostrumproject.eu [email protected] +972-48294018 +972-54-4563384 Bridging the Legal-Institutional Gap in Mediterranean Coastline Management MARE NOSTRUM PROJECT FINAL REPORT Legal-Institutional Instruments for Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) in the Mediterranean Technion Academic Team: Rachelle Alterman (head), Dafna Carmon, Cygal Pellach, Raanan Boral, Na’ama Teschner Project management: Raanan Boral, Cygal Pellach Additional research inputs: Elena Korotkova, Safira De La Sala, Dorit Garfunkel Administrative-financial Coordinator: Simon Van Dam Cover Design: Cygal Pellach Mare Nostrum Project ENPI CBC MSB Grant Agreement I-A/1.3/093 MARE NOSTRUM marenostrumproject.eu [email protected] +972-48294018 +972-54-4563384 © 2016 by the Mare Nostrum Partnership Statement about the Programme: The 2007-2013 ENPI CBC Mediterranean Sea Basin (MSB) Programme is a multilateral Cross-Border Cooperation initiative funded by the European Neighbourhood and Partnership Instrument (ENPI). The Programme objective is to promote the sustainable and harmonious cooperation process at the Mediterranean Basin level by dealing with the common challenges and enhancing its endogenous potential. It finances cooperation projects as a contribution to the economic, social, environmental and cultural development of the Mediterranean region. -

How Best to Respond? Expert Meeting Djibuti, 8-10 November 2011

RefugeesRefugees andand asylumasylum--seekersseekers inin distressdistress atat seasea –– howhow bestbest toto respondrespond?? ExpertExpert meetingmeeting DjibutiDjibuti,, 88--1010 NovemberNovember 20112011 AUTHORITIES INVOLVED IN RESCUE AT SEA Central Directorate Strategic Coordination Navy Navy CoCoastast Guard Operational guidance in high seas Operational guidance for S.A.R. events Guardia di Finanza Police & Carabinieri Operational guidance in territorial waters Close shore line patrolling PrincipalPrincipal FlowsFlows towardstowards ItalyItaly From TUNISIA EGADI ISLANDS TUNISI TUNISIA LINOSA LAMPEDUSA SOUSSE MADIJA * Up to 5 November DATA ON LANDINGS YEARS LANDINGS MEN WOMEN MINOR TOTAL 2009 39 391 1 7 399 2010 51 560 2 52 614 2011* 512 26.682 235 1.102 28.019** **Landing in Lampedusa 25.714 Landing in Linosa 429 In 2011 have been arrested 73 smugglers and facilitators and 337 boats have been confiscated. In the 2010, were arrested only 7 persons and 19 boats were confiscated. Modus Operandi from Tunisia • By zodiac or wooden boat, of about 4 to 15 meters in length with 3 to 279 persons aboard (on a boat of 12 meters in length) • By fishing boats of 15/25 meters in length (maximum 344 persons aboard a boat of 15 meters in length) • Principally young males • Many trips are self-organized • Nocturnal departure • The cost is about 1,500/2,000 dinars • The Tunisians, generally, claim to want to reach northern Europe From LIBYA SICILY LINOSA LAMPEDUSA TRIPOLI ZUARA MISRATAH LIBYA * Up to 26 may DATA ON LANDINGS YEARS LANDINGS MEN WOMEN MINOR TOTAL 2009 55 4,928 896 466 6,290 2010 9 279 10 57 346 2011* 99 23.137 3.016 1.985 28.318 In 2011 have been arrested 51 smugglers and facilitators and have been confiscated 60 boats. -

Join Indian Coast Guard (Ministry of Defence) As Navik (General Duty) 10+2 Entry - 02/2018 Batch Application Will Be Accepted ‘Online’ from 24 Dec 17 to 02 Jan 18

1 JOIN INDIAN COAST GUARD (MINISTRY OF DEFENCE) AS NAVIK (GENERAL DUTY) 10+2 ENTRY - 02/2018 BATCH APPLICATION WILL BE ACCEPTED ‘ONLINE’ FROM 24 DEC 17 TO 02 JAN 18 1. Applications are invited from male Indian nationals possessing educational qualifications and age, as prescribed below, for recruitment to the post of Navik (General Duty) in the Indian Coast Guard, an Armed Force of the Union. 2. Educational Qualification. 10+2 passed with 50% marks aggregate in total and minimum 50% aggregate in Maths and Physics from an education board recognized by Central/State Government. (5 % relaxation in above minimum cut off will be given for SC/ST candidates and outstanding sports person of National level who have obtained 1st, 2nd or 3rd position in any field sports events at the Open National Championship/ Interstate National Championship. This relaxation will also be applicable to the wards of Coast Guard uniform personnel deceased while in service). 3. Age. Minimum 18 Years and maximum 22 years i.e. between 01 Aug 1996 to 31 Jul 2000 (both dates inclusive). Upper age relaxation of 5 years for SC/ST and 3 years for OBC candidates. 4. Pay, Perks and Others Benefits:- On joining Indian Coast Guard, you will be placed in Basic pay Rs. 21700/- (Pay Level-3) plus Dearness Allowance and other allowances based on nature of duty/place of posting as per the regulation enforced time to time. 5. Promotion and Perquisites. (a) Promotion prospects exist up to the rank of Pradhan Adhikari with pay scale Rs. 47600/- (Pay Level 8) with Dearness Allowance. -

The Precarious Position of NGO Safe and Rescue Operations in the Central Mediterranean

05 2 0 1 7 (NOUVELLE SÉRIE- VERSION ÉLECTRONIQUE) UNCERTAINTY, ALERT AND DISTRESS: THE PRECARIOUS POSITION OF NGO SEARCH AND RESCUE OPERATIONS IN THE CENTRAL MEDITERRANEAN ADAM SMITH1 I. INTRODUCTION – II. INTERNATIONAL SAR FRAMEWORK, CURRENT CRISIS AND RESPONSES – III- OPPOSITION TO NGO DEPLOYERS – IV. LEGAL EVALUATION OF ANTI-NGO POLICIES, CURRENT AND EXPECTED – V- CONCLUSIONS AND OBSERVATIONS ABSTRACT: The international framework for maritime search and rescue relies on state actors establishing regions of responsibility supported by private shipmasters acting in compliance with traditional duties to rescue persons in distress at sea. Despite revisions to the framework’s founda- tional treaty, questions persist about the extent of state responsibilities and the interaction between those responsibilities and international human rights law. Over the past three years, non-govern- mental organizations (NGOs) have provided significant support to the efforts of sovereign actors responding to the migration crisis in the Central Mediterranean. Regional governments and civil society initially praised NGO operations, but in recent months these groups have come to criticize and challenge such operations. Italian authorities have threatened criminal prosecution of NGO de- ployers and proposed closing national ports to them. Libyan authorities have harassed NGO vessels and sought to exclude them from international waters. These actions are consistent with non-entrée strategies employed by Mediterranean states in recent years, but are in certain cases of questionable legality. Although controlling irregular migration is properly the responsibility of state actors, re- cent policies are inconsistent with principles of rule of law and good governance. KEYWORDS: irregular migration; maritime law; Search and Rescue regime; NGOs; Italy; Libya; human rights. -

Ouest Tribune

MÉDÉA DEUX BOMBES ARTISANALES DÉTRUITES P. 2 SOLIDARITÉ EDDALIA APPELLE LES PRIVÉS À INVESTIR DANS SON SECTEUR P. 2 Jeudi 22 Août 2019 - N°7726 - Prix: 20 DA - 13, Cité Djamel Oran - Tél: 041 85 80 48 - Fax: 041 85 82 54 - www.ouestribune-dz.com DIALOGUE NATIONAL INCLUSIF LeLe panelpanel intensifieintensifie sesses rencontresrencontres Lire page 3 L’HÉCATOMBE SE POURSUIT 22 PÈLERINS SUR LES ROUTES ALGÉRIENS DÉCÉDÉS DEPUIS 74 MORTS ET PLUS LE DÉBUT DU DE 270 BLESSÉS HADJ 2019 P. 3 EN UNE SEMAINE P. 2 2 Ouest Tribune Jeudi 22 Août 2019 EVENEMENT MÉDÉA L’HÉCATOMBE SE POURSUIT SUR LES ROUTES Deux 74 morts et plus de 270 blessés bombes en une semaine artisanales Samir Hamiche Selon les services de la gendarmerie nationale, 74 personnes ont été toute la société et, en premier détruites lieu, le conducteur. tuées alors que 271 autres ont été blessées dans plus de 170 accidents eux bombes de es chiffres des acci- de la route survenus entre le 13 et 19 août de ce mois. A ce jour, tous les moyens dents de la circulation mis en œuvre pour contrer Dconfection Ldonnés par la Protec- selon le dernier bilan de la tons, le non-respect de la dis- de leur vie avec près de 3.500 cette situation chaotique artisanale ont été tion civile et la gendarmerie gendarmerie nationale. tance de sécurité et le non- personnes fauchées par la n’ont pas abouti, faisant de découvertes et nationale, sont toujours très Selon la gendarmerie, c’est respect de la priorité. Concer- route chaque année en Algé- la circulation dans la capi- détruites, mardi à élevés et alarmants notam- la wilaya de Bouira qui vient nant le nombre de morts, Ti- rie. -

Submission-Mare-Liberum

1 Submission to the Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants: pushback practices and their impact on the human rights of migrants by Mare Liberum Mare Liberum is a Berlin based non-profit-association, that monitors the human rights situation in the Aegean Sea with its own ships - mainly of the coast of the Greek island of Lesvos. As independent observers, we conduct research to document and publish our findings about the current situation at the European border. Since March 2020, Mare Liberum has witnessed a dramatic increase in human rights violations in the Aegean, both at sea and on land. Collective expulsions, commonly known as ‘pushbacks’, which are defined under ECHR Protocol N. 4 (Article 4), have been the most common violation we have witnessed in 2020. From March 2020 until the end of December 2020 alone, we counted 321 pushbacks in the Aegean Sea, in which 9,798 people were pushed back. Pushbacks by the Hellenic Coast Guard and other European actors, as well as pullbacks by the Turkish Coast Guard are not a new phenomenon in the Aegean Sea. However, the numbers were significantly lower and it was standard procedure for the Hellenic Coast Guard to rescue boats in distress and bring them to land where they would register as asylum seekers. End of February 2020 the political situation changed dramatically when Erdogan decided to open the borders and to terminate the EU-Turkey deal of 2016 as a political move to create pressure on the EU. Instead of preventing refugees from crossing the Aegean – as it was agreed upon in the widely criticised EU-Turkey deal - reports suggested that people on the move were forced towards the land and sea borders by Turkish authorities to provoke a large number of crossings. -

Tonnare in Italy: Science, History, and Culture of Sardinian Tuna Fishing 1

Tonnare in Italy: Science, History, and Culture of Sardinian Tuna Fishing 1 Katherine Emery The Mediterranean Sea and, in particular, the cristallina waters of Sardinia are confronting a paradox of marine preservation. On the one hand, Italian coastal resources are prized nationally and internationally for their natural beauty as well as economic and recreational uses. On the other hand, deep-seated Italian cultural values and traditions, such as the desire for high-quality fresh fish in local cuisines and the continuity of ancient fishing communities, as well as the demands of tourist and real-estate industries, are contributing to the destruction of marine ecosystems. The synthesis presented here offers a unique perspective combining historical, scientific, and cultural factors important to one Sardinian tonnara in the context of the larger global debate about Atlantic bluefin tuna conservation. This article is divided into four main sections, commencing with contextual background about the Mediterranean Sea and the culture, history, and economics of fish and fishing. Second, it explores as a case study Sardinian fishing culture and its tonnare , including their history, organization, customs, regulations, and traditional fishing method. Third, relevant science pertaining to these fisheries’ issues is reviewed. Lastly, the article considers the future of Italian tonnare and marine conservation options. Fish and fishing in the Mediterranean and Italy The word ‘Mediterranean’ stems from the Latin words medius [middle] and terra [land, earth]: middle of the earth. 2 Ancient Romans referred to it as “ Mare nostrum ” or “our sea”: “the territory of or under the control of the European Mediterranean countries, especially Italy.” 3 Today, the Mediterranean Sea is still an important mutually used resource integral to littoral and inland states’ cultures and trade. -

GAO-21-539, COVID-19: the Coast Guard Has Addressed Challenges

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Addressees July 2021 COVID-19 The Coast Guard Has Addressed Challenges, but Could Improve Telework Documentation and Personnel Data GAO-21-539 July 2021 COVID-19 The Coast Guard Has Addressed Challenges, but Could Improve Telework Documentation and Highlights of GAO-21-539, a report to Personnel Data congressional addressees Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found The Coast Guard is a multi-mission The U.S. Coast Guard took steps to safeguard its personnel during the COVID- maritime military service responsible 19 pandemic by updating its policies and guidance, expanding telework, and for maritime safety, security, and administering COVID-19 vaccines, among other efforts. For example, the Coast environmental protection, among other Guard formed a COVID-19 Crisis Action Team comprising targeted working things. During the pandemic, the Coast groups to address COVID-19-related issues and develop new policies and Guard has faced challenges in guidance. Further, from December 2020 through April 2021, the Coast Guard balancing the need to safeguard its administered vaccines to 35,439 (about 64 percent) of its personnel. personnel with its responsibility to continue missions and operations. Selected U.S. Coast Guard COVID-19 Crisis Action Team Working Groups In response to a CARES Act mandate and congressional requests, GAO reviewed the Coast Guard’s efforts to respond to the pandemic. This report examines (1) the Coast Guard’s actions to reduce the risk of COVID-19 exposure for its personnel; (2) challenges the Coast Guard faced in operating in a pandemic environment and how it addressed them; and (3) the extent to which the Coast Guard has The Coast Guard also took actions to address a variety of challenges posed by collected and maintained valid and the COVID-19 pandemic. -

Migration Germany Welcomes Refugees

per VOLUME 7, ISSUE 1, 2016 ConcordiamJournal of European Security and Defense Issues n WOLVES AMONG SHEEP? n MIGRANT DEMOGRAPHICS Refugees pose little terrorism threat The vulnerability of women and children n A LUCRATIVE ENTERPRISE PLUS Demand drives human smuggling The role of international law n LESSONS FROM HISTORY Fixing a broken system Europe’s experience with migration Germany welcomes refugees MIGRATION Balancing Human Rights and Security Table of Contents features ON THE COVER The flood of migrants into Europe, many moving through the Balkans to Germany, often face the rain and cold in search of a better life. THE ASSOCIATED PRESS 38 7 The Complexities of Migration 22 Terrorism and Mass Migration By Dr. Carolyn Haggis and Dr. Petra Weyland, Marshall Center By Dr. Sam Mullins, Marshall Center Faculty Overview Violent extremists rarely emerge from the ranks of Europe’s refugees. 10 Refugees in Europe By Dr. Anne Hammerstad 30 Alumni in Their Own Words Integrating asylum seekers — not freezing By Ana Breben of Romania, Rear Adm. (Ret.) Ivica immigration — is critical to pre-empting conflict. Tolić of Croatia, Maj. Bassem Shaaban of Lebanon, and Lt. Cmdr. Ilir Çobo of Albania (co-authored with Suard Alizoti) 18 A Practitioner’s Solution for Europe’s Four Marshall Center alumni detail how migration has impacted their countries. Migration Challenge By Kostas Karagatsos The European Union should appeal to its legal system to handle migration flows. 2 per Concordiam in every issue 4 DIRECTOR’S LETTER 5 CONTRIBUTORS 8 VIEWPOINT 64 BOOK REVIEW 66 CALENDAR 48 54 38 Countering Migrant Smuggling 54 A Legal Look at Migration By Rear Adm. -

Report 2021, No. 6

News Agency on Conservative Europe Report 2021, No. 6. Report on conservative and right wing Europe 20th March, 2021 GERMANY 1. jungefreiheit.de (translated, original by jungefreiheit.de, 18.03.2021) "New German media makers" Migrant organization calls for more “diversity” among journalists media BERLIN. The migrant organization “New German Media Makers” (NdM) has reiterated its demand that editorial offices should become “more diverse”. To this end, the association presented a “Diversity Guide” on Wednesday under the title “How German Media Create More Diversity”. According to excerpts on the NdM website, it says, among other things: “German society has changed, it has become more colorful. That should be reflected in the reporting. ”The manual explains which terms journalists should and should not use in which context. 2 When reporting on criminal offenses, “the prejudice still prevails that refugees or people with an international history are more likely to commit criminal offenses than biographically Germans and that their origin is causally related to it”. Collect "diversity data" and introduce "soft quotas" Especially now, when the media are losing sales, there is a crisis of confidence and more competition, “diversity” is important. "More diversity brings new target groups, new customers and, above all, better, more successful journalism." The more “diverse” editorial offices are, the more it is possible “to take up issues of society without prejudice”, the published excerpts continue to say. “And just as we can no longer imagine a purely male editorial office today, we should also no longer be able to imagine white editorial offices. Precisely because of the special constitutional mandate of the media, the question of fair access and the representation of all population groups in journalism is also a question of democracy.