JPH327682 for Web.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

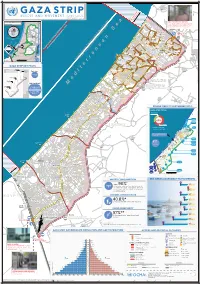

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

Introduction

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87598-1 - The War for Palestine: Rewriting the History of 1948, Second Edition Edited by Eugene L. Rogan and Avi Shlaim Excerpt More information Introduction The Palestine War lasted less than twenty months, from the United Nations resolution recommending the partition of Palestine in November 1947 to the final armistice agreement signed between Israel and Syria in July 1949. Those twenty months transformed the political landscape of the Middle East forever. Indeed, 1948 may be taken as a defining moment for the region as a whole. Arab Palestine was destroyed and the new state of Israel established. Egypt, Syria and Lebanon suffered outright defeat, Iraq held its lines, and Transjordan won at best a pyrrhic victory. Arab public opinion, unprepared for defeat, let alone a defeat of this magnitude, lost faith in its politicians. Within three years of the end of the Palestine War, the prime ministers of Egypt and Lebanon and the king of Jordan had been assassinated, and the president of Syria and the king of Egypt over- thrown by military coups. No event has marked Arab politics in the second half of the twentieth century more profoundly. The Arab–Israeli wars, the Cold War in the Middle East, the rise of the Palestinian armed struggle, and the politics of peace-making in all of their complexity are a direct con- sequence of the Palestine War. The significance of the Palestine War also lies in the fact that it was the first challenge to face the newly independent states of the Middle East. -

National Report, State of Palestine United Nations

National Report, State of Palestine United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat III) 2014 Ministry of Public Works and Housing National Report, State of Palestine, UN-Habitat 1 Photo: Jersualem, Old City Photo for Jerusalem, old city Table of Contents FORWARD 5 I. INTRODUCTION 7 II. URBAN AGENDA SECTORS 12 1. Urban Demographic 12 1.1 Current Status 12 1.2 Achievements 18 1.3 Challenges 20 1.4 Future Priorities 21 2. Land and Urban Planning 22 2. 1 Current Status 22 2.2 Achievements 22 2.3 Challenges 26 2.4 Future Priorities 28 3. Environment and Urbanization 28 3. 1 Current Status 28 3.2 Achievements 30 3.3 Challenges 31 3.4 Future Priorities 32 4. Urban Governance and Legislation 33 4. 1 Current Status 33 4.2 Achievements 34 4.3 Challenges 35 4.4 Future Priorities 36 5. Urban Economy 36 5. 1 Current Status 36 5.2 Achievements 38 5.3 Challenges 38 5.4 Future Priorities 39 6. Housing and Basic Services 40 6. 1 Current Status 40 6.2 Achievements 43 6.3 Challenges 46 6.4 Future Priorities 49 III. MAIN INDICATORS 51 Refrences 52 Committee Members 54 2 Lists of Figures Figure 1: Percent of Palestinian Population by Locality Type in Palestine 12 Figure 2: Palestinian Population by Governorate in the Gaza Strip (1997, 2007, 2014) 13 Figure 3: Palestinian Population by Governorate in the West Bank (1997, 2007, 2014) 13 Figure 4: Palestinian Population Density of Built-up Area (Person Per km²), 2007 15 Figure 5: Percent of Change in Palestinian Population by Locality Type West Bank (1997, 2014) 15 Figure 6: Population Distribution -

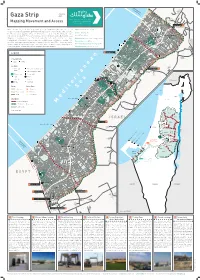

Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary

Zikim Karmiya No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles Yad Mordekhai January Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary Ar-Rasheed Wastewater Treatment Lagoons Sources: OCHA, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics of Statistics Bureau Central OCHA, Palestinian Sources: Erez Crossing 1 Al-Qarya Beit Hanoun Al-Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) Erez What is known today as the Gaza Strip, originally a region in Mandatory Palestine, was created Width 5.7-12.5 km / 3.5 – 7.7 mi through the armistice agreements between Israel and Egypt in 1949. From that time until 1967, North Gaza Length ~40 km / 24.8 mi Al- Karama As-Sekka the Strip was under Egyptian control, cut off from Israel as well as the West Bank, which was Izbat Beit Hanoun al-Jaker Road Area 365 km2 / 141 m2 Beit Hanoun under Jordanian rule. In 1967, the connection was renewed when both the West Bank and the Gaza Madinat Beit Lahia Al-'Awda Strip were occupied by Israel. The 1993 Oslo Accords define Gaza and the West Bank as a single Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Population 1,943,398 • 48% Under age 17 July 2019 Industrial Zone Ash-Shati Housing Project Jabalia Sderot territorial unit within which freedom of movement would be permitted. However, starting in the camp al-Wazeer Unemployment rate 47% 2019 Q2 Jabalia Camp Khalil early 90s, Israel began a gradual process of closing off the Strip; since 2007, it has enforced a full Ash-Sheikh closure, forbidding exit and entry except in rare cases. Israel continues to control many aspects of Percentage of population receiving aid 80% An-Naser Radwan Salah Ad-Deen 2 life in Gaza, most of its land crossings, its territorial waters and airspace. -

1948 Arab‒Israeli

1948 Arab–Israeli War 1 1948 Arab–Israeli War מלחמת or מלחמת העצמאות :The 1948 Arab–Israeli War, known to Israelis as the War of Independence (Hebrew ,מלחמת השחרור :, Milkhemet Ha'atzma'ut or Milkhemet HA'sikhror) or War of Liberation (Hebrewהשחרור Milkhemet Hashikhrur) – was the first in a series of wars fought between the State of Israel and its Arab neighbours in the continuing Arab-Israeli conflict. The war commenced upon the termination of the British Mandate of Palestine and the Israeli declaration of independence on 15 May 1948, following a period of civil war in 1947–1948. The fighting took place mostly on the former territory of the British Mandate and for a short time also in the Sinai Peninsula and southern Lebanon.[1] ., al-Nakba) occurred amidst this warﺍﻟﻨﻜﺒﺔ :Much of what Arabs refer to as The Catastrophe (Arabic The war concluded with the 1949 Armistice Agreements. Background Following World War II, on May 14, 1948, the British Mandate of Palestine came to an end. The surrounding Arab nations were also emerging from colonial rule. Transjordan, under the Hashemite ruler Abdullah I, gained independence from Britain in 1946 and was called Jordan, but it remained under heavy British influence. Egypt, while nominally independent, signed the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 that included provisions by which Britain would maintain a garrison of troops on the Suez Canal. From 1945 on, Egypt attempted to renegotiate the terms of this treaty, which was viewed as a humiliating vestige of colonialism. Lebanon became an independent state in 1943, but French troops would not withdraw until 1946, the same year that Syria won its independence from France. -

Chapter 5. Development Frameworks

Chapter 5 JERICHO Regional Development Study Development Frameworks CHAPTER 5. DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORKS 5.1 Socioeconomic Framework Socioeconomic frameworks for the Jericho regional development plan are first discussed in terms of population, employment, and then gross domestic product (GDP) in the region. 5.1.1 Population and Employment The population of the West Bank and Gaza totals 3.76 million in 2005, according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) estimation.1 Of this total, the West Bank has 2.37 million residents (see the table below). Population growth of the West Bank and Gaza between 1997 and 2005 was 3.3%, while that of the West Bank was slightly lower. In the Jordan Rift Valley area, including refugee camps, there are 88,912 residents; 42,268 in the Jericho governorate and 46,644 in the Tubas district2. Population growth in the Jordan Rift Valley area is 3.7%, which is higher than that of the West Bank and Gaza. Table 5.1.1 Population Trends (1997-2005) (Unit: number) Locality 1997 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 CAGR West Bank and Gaza 2,895,683 3,275,389 3,394,046 3,514,868 3,637,529 3,762,005 3.3% West Bank 1,873,476 2,087,259 2,157,674 2,228,759 2,300,293 2,372,216 3.0% Jericho governorate 31,412 37,066 38,968 40,894 40,909 42,268 3.8% Tubas District 35,176 41,067 43,110 45,187 45,168 46,644 3.6% Study Area 66,588 78,133 82,078 86,081 86,077 88,912 3.7% Study Area (Excl. -

Summary of Consultation on Effects of the COVID-19 on Women in Palestine

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics A Summary of Statistical Indicators on Women in Palestine during the Covid19 Crises Most Vulnerable Women Segments Around 10,745 women Health care health system workers and a total of 31,873 workers men and women 900 women working in workers in Palestine Women working in Israel Israel and settlements and settelements mostly in agriculture 175891 total females with chronic Women with Chronic disease 69,112 women suffer from at least one Chronic Disease (60+) Disease The percentage of poverty Female Childen with disease 9,596 female among households headed children with chronic by women in 2017 was 19% in the WB and 54% in Poor women Gaza Strip Elderly women In 2020 there are 140 287 60+ women 92,584 women heading households (61241 WB, Women Heading households 31343 Gaza Strip – 41,017 of highest in Jericho women have Women with disabilities at least one type of disability 1 Social Characteristics 1. The elderly (the most vulnerable group) • The number of elderly people (60+ years) in the middle of 2020 is around 269,346, (5.3% women, 140,287, and 129,059 men) • The percentage of elderly in Palestine was 5.0% of the total population in 2017 (5.4% for the elderly females, 4.6% for the elderly males), and in the West Bank it is higher than in the Gaza Strip (5.4 % In the West Bank and 4.3% in the Gaza Strip). • At the governorate level, the highest percentage of elderly people was in the governorates of Tulkarm, Ramallah, Al-Bireh, Bethlehem, and Jerusalem (6.5%, 6.0%, 6.0%, and 5.9%, respectively). -

Healing the Holy Land: Interreligious Peacebuilding in Israel/Palestine

Healing the Holy Land Interreligious Peacebuilding in Israel/Palestine Yehezkel Landau United States Institute of Peace Contents Summary 5 Foreword by David Smock 7 1. Introduction 9 2. Religion: A Blessing or a Curse? 11 3. After the Collapse of Oslo 13 4. The Alexandria Summit and Its Aftermath 16 5. Grassroots Interreligious Dialogues 26 6. Educating the Educators 29 7. Other Muslim Voices for Interreligious Peacebuilding 31 8. Symbolic Ritual as a Mode of Peacemaking 35 9. Active Solidarity: Rabbis for Human Rights 38 10. From Personal Grief to Collective Compassion 41 11. Journeys of Personal Transformation 44 12. Practical Recommendations 47 Appendices 49 About the Author 53 About the Institute 54 Summary ven though the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is primarily a political dispute between two nations over a common homeland, it has religious aspects that Eneed to be addressed in any effective peacemaking strategy. The peace agenda cannot be the monopoly of secular nationalist leaders, for such an approach guarantees that fervent religious believers on all sides will feel excluded and threatened by the diplo- matic process. Religious militants need to be addressed in their own symbolic language; otherwise, they will continue to sabotage any peacebuilding efforts. Holy sites, including the city of Jerusalem, are claimed by both peoples, and deeper issues that fuel the conflict, including the elements of national identity and purpose, are matters of transcendent value that cannot be ignored by politicians or diplomats. This report argues for the inclusion of religious leaders and educators in the long-term peacebuilding that is required to heal the bitter conflict between Israelis and Palestinians. -

Land Ownership in Palestine

LAND OWNERSHIP IN PALESTINE ... ·'·"" ·'· * Sami Hadawi THE PALESTINE ARAB R ~ FUGEE OFFICE 801 2od Avenue, 1o... 801 New York 17, N. Y. LAND OWNERSHIP IN PALESTINE -·- SAMI HADAWI THE PALESTINE ARAB REFUGEE OFFICE 801 2nd Avenue, Room 801 New York 17, N. Y. January 1957 This material is filed with the Department of Justice, where the required statement of "The Palestine Arab Refugee Office," registration No. 897, is available for inspection. Registration does not imply approval O'r disapproval of this material by the United States Government. FOREWORD Most of the material which has been written about Palestine since the tragedy of 1948, has dealt with the political side of the issue. The Israeli propaganda machine tries to give the impression to the outside world that the Palestine problem is nothing more than a case of~ dispute over a country which legally and legitimately belongs to the Jews and which the Arab States covet to annex to their own vast territories. As such, all other problems affecting the rights and interests of the Arab inhabitants of Palestine are of a secondary nature. The fact that is generally over-shadowed by this Israeli and Zionist propaganda, and w,hich, as a result, has been overlooked by world opinion so far as Palestine is concerned, is that the status of a country as belonging to a particular people is judged by the natural rights of the individuals who have been born and have tilled its soil for generations, rather than governed by political or other considerations. For the last four decades, Zionist propaganda has given a distorted picture of the situation in the Holy Land. -

West Bank Snapshot Draft6

Occupied Palestinian territory: West Bank, June-August 2014 Concern over excessive use of force The period between June and August 2014 was marked by heightened tensions and clashes across the West Bank, alongside concerns over excessive use of force by Israeli forces in crowd control situations. The resulting rise in casualties started amid Israeli military operations triggered by the abduction and killing of three Israeli youths near Bethlehem, on 12 June, and continued in the context of protests against the abduction and killing of a Palestinian boy in East Jerusalem, on 2 July, and against the Israeli offensive in the Gaza Strip between 7 July and 26 August. These events exacerbated pre-existing tensions, including as a result of the continuous settlement expansion and the collapse of the peace negotiations. 2014 timeline of events & casualties Casualties by governorate June - August Day Palestinian injuries End of Gaza offensive 26 1949 Armistice Jenin 619 (Green Line) P August 52 8 Fatalities Tubas Re-arrest of Palestinian P prisoners released during the July Tulkarm 18 2,213 P 5 “Shalit deal” 57 Start of Gaza offensive 7 14 Fatalities R Palestinian boy 2 Nablus kidnapped and killed P VE Bodies of 3 Israeli 30 Qalqiliya I youths found P 203 R 3 Israeli youths 12 June 63by live kidnapped and killed 270 96 N ammunition A D Pal. National Consensus 2 6 Fatalities Government formed P R Salfit O 39 J May 236 48 Members of Israeli West Bank forces injured “Nakba day” demonstrations 5 2 Fatalities June - August Ramallah End of Israeli-Palestinian P negotiations 24 Jericho Fatah and Hamas 23 P conclude a unity pact. -

Viewing the Tanzimat from Tulkarm According to Al-Salim: “The 1858 Land Code Changed the Social Pyramid and the Economic Structure of Palestine” (77)

Viewing the Tanzimat The Ottoman Empire began its rule in Palestine in 1517 and prevailed almost from Tulkarm continuously until the end of the First World War in 1918. The literature on Palestine and the Decline of the Ottoman Palestine under Ottoman rule is vast and Empire: Modernization and the Path to ranges from comprehensive accounts Palestinian Statehood, by Farid al-Salim. to specific case studies. Recent works London: I. B. Tauris, 2015. ix + 206 pages, have focused on the impact of nineteenth notes, bibliography, and index to 260. century Ottoman reforms efforts – or $110.00 cloth. Tanzimat, as they are known in Ottoman history – which represented an overall Reviewed by Ahmed H. Ibrahim reorganization in every institution of state and society. The reforms targeted tax collection, military conscription, education, and the legal system. The reforms aimed at reasserting central control within the empire and forestalling further European encroachment. Farid al-Salim’s Palestine and the Decline of the Ottoman Empire highlights the role of the Ottoman administrative system and the new social structure in Palestine in the final decades of Ottoman rule. The book is mainly concerned with the impact of the late Ottoman reforms effort on the new administrative centers and countryside of Palestine. The author examines the history of the district of Tulkarm between 1876 and 1918 as a case study of a small village in central Palestine that was transformed into a center of administrative reforms. The key argument in this book is that, as the Ottoman Empire approached its final years, the reforms that the empire initiated during the 1839–1876 period contributed significantly to forming the administrative foundation of the modern Palestinian entity. -

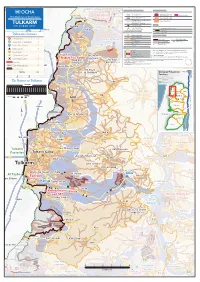

Tulkarm TULKARM

¹º» !P !P At Tarem ?B65 P!!P Khirbet al Muntar Tura !P !P !P Khirbet al MuntarClosed and Restricted Areas Arab alIsraeli Settlements al Gharbiya !P ash Sharqiya Nazlat ash !P Israeli military base Hamdun Settlement built-up , outer Access is prohibited Settlement Outpost B?6 Reikhan Umm Dar !P limit andSheikh municipal area Zeid West Bank Access Restrictions IsraeliAl closed Khuljan military area Land cultivated by settlers Dhaher al 'Abed Access is prohibited Barta'a Existing and projected 'closed areas' % GF Israeli Nature Reserve !P !P Zabda behind the Barrier Adebal GF %¹º» !P !P !P Qeiqis Access is limited to permit holders Ya'bad TULKARMSha'ar Menashe Tunnel/Underpass* Roads Kufeirit OCTOBER 2017 Akkaba !T # P! Observation Tower* !P Al Manshiya !P Prohibited Palestinian vehicle use !P ") * Not counted in the total closure figures. Meiser Khirbet Mas'ud Main road % Palestinian Communities Ya'bad # Other road Tulkarem Closures Governorate Capital Mevo Dotan % ## # West Bank Barrier ImreihaGovernorate Boundry Checkpoints 5 Qaffin !P % ¹º» !P Khirbet Fraseen Built-up %Constructed Planned Re-routing !P Green Line Checkpoints 2 < 1000 Residents Under Construction Barrier Gate GF Khirbet1000 al - 10,000 Mkahhal EG % !P Planned Route Partial Checkpoints 2 Fraseen % > 10,000 Jabal al Aqra'a !P Occupied Palestinian!P Oslo Interim Agreements (1995-1999)Maoz Zvi Earthmounds 9 585 B? 1 Area ATerritory 1. Extensive delegation of powers to the PalestinianL E AuthorityB A N O N Roadblocks - !P Area B2 2. Partial delegation of powers to the Palestinian Authority; joint Khirbet al-Hamaam Israeli-Palestinian security coordination GF Special Case (H2)3 Nazlat 'Isa 3.