Villacorta Nov 2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Room Assignment for Foxpro Dbase Version 1.0 (C) Lloyd A

PROFESSIONAL REGULATION COMMISSION Davao Regional Office Licensure Examination for TEACHERS (CONTENT COURSE) SEPTEMBER 30, 2012 School: TEODORO L. PALMA GIL ELEM. SCH. Address: QUIRINO AVE., DAVAO CITY Bldg.: PALMA GIL Floor: GF Room/Grp No.: 1 Seat Last Name First Name Middle Name School Attended No. 1 AA BANSAG JENIFFER DAGSAN RIZAL MEMORIAL COLLEGE 2 AA BIANTAN MICHELLE FAGTANAN MINDANAO STATE UNIVERSITY-GEN. SANTOS CITY 3 AA CERVANTES NOVA SOLANTE DAVAO ORIENTAL STATE COLLEGE OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY 4 AA DEL PERO LEOVANYL OROCIO NORTH DAVAO COLLEGES-PANABO 5 AA ENERO CLAIRE SUA-AN MINDANAO STATE UNIVERSITY-GEN. SANTOS CITY 6 AA ENTAL IZAFAITH ALONZO DAVAO CENTRAL COLLEGE 7 AA LARITA ANGELYN PONTILLO SAINT VINCENT DE PAUL COLLEGE-BISLIG 8 AA LORETE MARITES SUMBILING CENTRAL MINDANAO COLLEGES 9 AA LUARDO JORAMAE LABANDIA DAVAO ORIENTAL STATE COLLEGE OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY 10 AA MANAGZA MAIMONA KAMSARI SPA COLLEGE, INC. 11 AA MIPANTAO MELANIE KUSAIN NOTRE DAME UNIVERSITY 12 AA ORCULLO ANALOU CAÑETE HOLY CROSS OF DAVAO COLLEGE 13 AA RUBIO ARLENE LAVADOR UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHEASTERN PHILIPPINES-TAGUM 14 AA SARONA JESHIREL TUBURAN MINDANAO STATE UNIVERSITY-GEN. SANTOS CITY 15 ABABAT KARL LEAH AMPALID UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN MINDANAO-KABACAN 16 ABABON CRISTY MELLORES DAVAO DOCTORS COLLEGE, INC. 17 ABAD GRITTLE JOY ZABALA UNKNOWN 18 ABAD ROMELIN LINDO BUKIDNON STATE COLLEGE-MALAYBALAY 19 ABADIEZ JENNIFER SALVANI UNKNOWN 20 ABAG BAILING PINGUIAMAN MINDANAO CAPITOL COLLEGE 21 ABAG FARIDA GUIAMEL QUEZON COLLEGES OF SOUTHERN PHILLIPINES REMINDER: USE SAME NAME IN ALL EXAMINATION FORMS. IF THERE IS AN ERROR IN SPELLING AND OTHER DATA KINDLY REQUEST YOUR ROOM WATCHERS TO CORRECT IT ON THE FIRST DAY OF EXAMINATION. -

AUGUST 2019 ISSN 2094-6570 Vol

Inside Marketers urge tech gens to tell their stories ...................................................... p2 DOST, PayMaya partnership a win-win for OneSTore.ph clients, merchants ..................... p3 DOST-PAGASA weather station to rise p4 12 years of bringing in Siquijor ......................................................... S&T good news InFocus ............................................................ p4 AUGUST 2019 ISSN 2094-6570 Vol. 12 No. 8 Innovation spurs PH’s forward jump in global index, science chief says Text & photo by Rodolfo P. De Guzman, DOST-STII where SETUP beneficiaries can market their products online. He also mentioned OneLab in which the DOST provides laboratory testing and analysis of MSMEs’ products through a network of laboratories nationwide. “With the OneLab project we are able to provide testing and analysis services to our MSMEs in the regions without them going to Manila because DOST will take care of forwarding the material to laboratories that are capable of testing the desired parameters,” explained Sec. de la Peña. “After the testing, the results are forwarded to the clients. They no longer have to make follow ups.” The science chief cited that the laboratories of the Department of Health plus some 10 private laboratories are already part of the network, including two laboratories in Thailand and one in Vietnam. To strengthen the research and development epartment of Science and Technology PH jumps to 54th in (R&D) efforts of the Department, Sec. de la Secretary Fortunato T. de la Peña Peña said that the Science for Change Program Dbannered the Philippines’ innovation 2019 from 73rd in 2018 was created in close collaboration with state strengths as contributing factor to the universities and colleges based in the regions. -

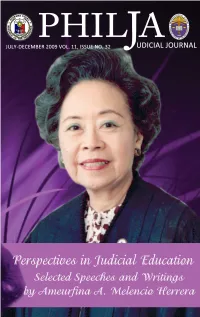

The PHILJA Judicial Journal

The PHILPHILPHIL AAA JULY-DECEMBER 2010 VOL. 12, ISSUE NO. 34 JJUDICIAL OURNAL LAW AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT The PHILJA Judicial Journal The PHILJA Judicial Journal is published twice a year by the Research, Publications and Linkages Office of the Philippine Judicial Academy (PHILJA). The Journal features articles, lectures, research outputs and other materials of interest to members of the Judiciary, particularly judges, as well as law students and practitioners. The views expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the views of either the Academy or its editorial board. Editorial and general offices are located at PHILJA, 3rd Floor, Centennial Building, Supreme Court, Padre Faura St., Manila. Tel. No.: 552-9524 Telefax No.: 552-9628 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] CONTRIBUTIONS. The PHILJA Judicial Journal invites contributions. Please include author’s name and biographical information. The editorial board reserves the right to edit the materials submitted for publication. Copyright © 2010 by The PHILJA Judicial Journal. All rights reserved. For more information, please visit the PHILJA website at http://philja.judiciary.gov.ph. ISSN 2244-5854 SUPREME COURT OF THE PHILIPPINES CHIEF JUSTICE Hon. RENATO C. CORONA ASSOCIATE JUSTICES Hon. ANTONIO T. CARPIO Hon. CONCHITA CARPIO MORALES Hon. PRESBITERO J. VELASCO, Jr. Hon. ANTONIO EDUARDO B. NACHURA Hon. TERESITA J. LEONARDO-DE CASTRO Hon. ARTURO D. BRION Hon. DIOSDADO M. PERALTA Hon. LUCAS P. BERSAMIN Hon. MARIANO C. DEL CASTILLO Hon. ROBERTO A. ABAD Hon. MARTIN S. VILLARAMA, Jr. Hon. JOSE P. PEREZ Hon. JOSE C. MENDOZA Hon. MARIA LOURDES P. A. SERENO COURT ADMINISTRATOR Hon. JOSE MIDAS P. -

Commencing the Pre-Judicature Program

The PHILJA Judicial Journal The PHILJA Judicial Journal is published twice a year by the Research, Publications and Linkages Office of the Philippine Judicial Academy (PHILJA). The Journal features articles, lectures, research outputs and other materials of interest to members of the Judiciary, particularly judges, as well as law students and practitioners. The views expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the views of either the Academy or its editorial board. Editorial and general offices are located at PHILJA, 3rd Floor, Centennial Building, Supreme Court, Padre Faura St., Manila. Tel. No.: 552-9524 Telefax No.: 552-9628 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] CONTRIBUTIONS. The PHILJA Judicial Journal invites contributions. Please include the author’s name and biographical information. The editorial board reserves the right to edit the materials submitted for publication. Copyright © 2010 by The PHILJA Judicial Journal. All rights reserved. For more information, please visit the PHILJA website at http://philja.judiciary.gov.ph. SUPREME COURT OF THE PHILIPPINES CHIEF JUSTICE Hon. REYNATO S. PUNO ASSOCIATE JUSTICES Hon. ANTONIO T. CARPIO Hon. RENATO C. CORONA Hon. CONCHITA CARPIO MORALES Hon. MINITA V. CHICO-NAZARIO Hon. PRESBITERO J. VELASCO, Jr. Hon. ANTONIO EDUARDO B. NACHURA Hon. TERESITA J. LEONARDO-DE CASTRO Hon. ARTURO D. BRION Hon. DIOSDADO M. PERALTA Hon. LUCAS P. BERSAMIN Hon. MARIANO C. DEL CASTILLO Hon. ROBERTO A. ABAD Hon. MARTIN S. VILLARAMA, Jr. COURT ADMINISTRATOR Hon. JOSE P. PEREZ DEPUTY COURT ADMINISTRATORS Hon. NIMFA C. VILCHES Hon. JOSE MIDAS P. MARQUEZ Hon. JESUS EDWIN A. VILLASOR CLERK OF COURT Atty. -

Total 12,635

TOTAL 12,635 Extension City/ First Name Middle Name Last Name Province Barangay Name Municipality MARCELINA P ACLIN Apayao Calanasan Eleazar REO P ACLIN Apayao Calanasan Eleazar JERICK C LANOG Apayao Calanasan Eleazar DIONICIO T DAGON Apayao Calanasan Eleazar FREDERICK - DALIWAG Apayao Calanasan Eleazar MARCEL SILAO DAGON Apayao Calanasan Eleazar NATIVIDAD A ABIAWAN Apayao Calanasan Eleazar NARSALIN ABIAWAN BAYANI Apayao Calanasan Eleazar ANDY - CORPUZ Apayao Calanasan Eleazar REY-ANN A BARTOLOME Apayao Calanasan Eleazar MEDY P LANOG Apayao Calanasan Eleazar JONEL T ABIAWAN Apayao Calanasan Eleazar WILFREDO - ULANGAN Apayao Calanasan Eleazar NOEL AGUBO ULANGAN Apayao Calanasan Eleazar MARIANO B ABIAWAN JR Apayao Calanasan Eleazar MORNEL S DAGON Apayao Calanasan Eleazar GLENN BRYLE GREGORIO RAUSA Apayao Calanasan Sabangan LARRY DACUSEN BONIFACIO Apayao Calanasan Don Roque Ablan Sr. LEGASPI SAGGUED AQUINO Apayao Calanasan Don Roque Ablan Sr. ROSITA LANGANAY SINOLENG Apayao Calanasan Don Roque Ablan Sr. JUNEZA GUDAYAN PAGMAAT Apayao Calanasan Don Roque Ablan Sr. WILMA L ABANGON Apayao Calanasan Don Roque Ablan Sr. RODERICK GANAB TAGACLAT Apayao Calanasan Don Roque Ablan Sr. JOSE DAGNAY GABENG Apayao Calanasan Don Roque Ablan Sr. ROGER R ULABO Apayao Calanasan Don Roque Ablan Sr. ELDEN B VICENTE Apayao Calanasan Don Roque Ablan Sr. HINER M DARISAN Apayao Calanasan Don Roque Ablan Sr. MARINO ABANGON LAGUESAD Apayao Calanasan Don Roque Ablan Sr. JENIE L JOAQUIN Apayao Calanasan Don Roque Ablan Sr. SANY BANGLAY ACANDA Apayao Calanasan Don Roque Ablan Sr. SYRINE A JOAQUIN Apayao Calanasan Don Roque Ablan Sr. PRISCO LANGANAY JOAQUIN Apayao Calanasan Don Roque Ablan Sr. EFREN SALNO LANGANAY Apayao Calanasan Don Roque Ablan Sr. -

Clov) (Seafarer

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES COMMISSIONS ON ELECTIONS OFFICE FOR OVERSEAS VOTING CERTIFIED LIST OF OVERSEAS VOTERS (CLOV) (SEAFARER) Source: Server Seq No. Voter's Name REGISTRATION DATE 1 ABA, REGINALD PATRON September 28, 2014 2 ABAA, ADRIAN SIMBORIO February 26, 2015 3 ABABA, JOVITO SUMAYAO October 03, 2012 4 ABABON, MELECIO VARGA October 10, 2014 5 ABACIAL, JEAM URIEL BOHOS March 26, 2018 6 ABAD, ALDIN BIANZON August 07, 2014 7 ABAD, ALDRICH BRAVO November 10, 2014 8 ABAD, ALFONSO JR. LOPEZ September 18, 2015 9 ABAD, ANABELLE NAMBAYAN September 16, 2015 10 ABAD, ANTONIO JR. VASQUES August 28, 2015 11 ABAD, AUGUSTO DIZON February 11, 2015 12 ABAD, BRIAN LAWAY October 26, 2015 13 ABAD, CARLA MICHELLE PUNIO May 07, 2015 14 ABAD, CESAR JR. ORALLO July 07, 2015 15 ABAD, DIGO BETUA January 28, 2015 16 ABAD, EDGARDO BUSA September 13, 2012 17 ABAD, EDUWARDO DE LUMEN September 24, 2018 18 ABAD, ERNESTO ESMAO August 11, 2015 19 ABAD, ERWIN TRINOS May 06, 2006 20 ABAD, FERDINAND BENTULAN August 07, 2014 21 ABAD, GERALD QUIL MAPANAO August 25, 2015 22 ABAD, HECTOR PASION August 05, 2015 23 ABAD, HERMIE MANALO August 28, 2015 24 ABAD, JEFFREY BRAVO May 25, 2018 25 ABAD, JOEL FRANCIA September 29, 2015 26 ABAD, JOEL RODRIGUEZ October 05, 2006 27 ABAD, JOHN CHESTER ABELLA August 05, 2015 28 ABAD, MARLON EVANGELISTA November 16, 2017 29 ABAD, NERIE GERSALIA January 17, 2018 30 ABAD, NOLI SOMIDO October 13, 2015 31 ABAD, PATRICK GACULA January 24, 2018 32 ABAD, RICKY MOJECA September 21, 2018 33 ABAD, ROMULO CERVANTES April 20, 2012 34 ABAD, RONALD TAN May 08, 2017 35 ABADAM, ALAN BASILIA August 19, 2012 NOTICE: All authorized recipients of any personal data, personal information, privileged and sensitive personal information contained in this document including other pertinent documents attached thereto that are shared by the Commission on Elections in compliance with the existing laws and rules, and in conformity with the Data Privacy Act of 2012 ( R.A. -

Chief Justice Reynato S. Puno Distinguished Lectures Series of 2010

The PHILJA Judicial Journal The PHILJA Judicial Journal is published twice a year by the Research, Publications and Linkages Office of the Philippine Judicial Academy (PHILJA). The Journal features articles, lectures, research outputs and other materials of interest to members of the Judiciary, particularly judges, as well as law students and practitioners. The views expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the views of either the Academy or its editorial board. Editorial and general offices are located at PHILJA, 3rd Floor, Centennial Building, Supreme Court, Padre Faura St., Manila. Tel. No.: 552-9524 Telefax No.: 552-9628 Email: [email protected]; [email protected] CONTRIBUTIONS. The PHILJA Judicial Journal invites contributions. Please include author’s name and biographical information. The editorial board reserves the right to edit the materials submitted for publication. Copyright © 2010 by The PHILJA Judicial Journal. All rights reserved. For more information, please visit the PHILJA website at http://philja.judiciary.gov.ph. ISSN 2244-5854 SUPREME COURT OF THE PHILIPPINES CHIEF JUSTICE Hon. RENATO C. CORONA ASSOCIATE JUSTICES Hon. ANTONIO T. CARPIO Hon. CONCHITA CARPIO MORALES Hon. PRESBITERO J. VELASCO, Jr. Hon. ANTONIO EDUARDO B. NACHURA Hon. TERESITA J. LEONARDO-DE CASTRO Hon. ARTURO D. BRION Hon. DIOSDADO M. PERALTA Hon. LUCAS P. BERSAMIN Hon. MARIANO C. DEL CASTILLO Hon. ROBERTO A. ABAD Hon. MARTIN S. VILLARAMA, Jr. Hon. JOSE P. PEREZ Hon. JOSE C. MENDOZA COURT ADMINISTRATOR Hon. JOSE MIDAS P. MARQUEZ DEPUTY COURT ADMINISTRATORS Hon. NIMFA C. VILCHES Hon. EDWIN A. VILLASOR Hon. RAUL B. VILLANUEVA CLERK OF COURT Atty. MA. -

MILF to Government

Vol. 3 No. 6 June 2008 Peace Monitor Pact among MNLF factions further confuses Central Mindanao sectors COTABATO CITY – The “Tripoli Declaration” forged by factions in the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) last May 18 further confused different sectors in Central Mindanao on who really is at the helm of the front’s central leadership. In the declaration, 10 MNLF leaders, including Nur [PACT /p.11] HOMEWARD BOUND --- A Malaysian military transport plane that brought members of the International Monitoring to Mindanao in 2003 will be frequenting Central Mindanao again to gradually transport IMT members home as part of the programmed pull out in batches of ceasefire monitors in the South.[] MILF to government: Pursue talks COTABATO CITY (Tuesday, June 3, 2008) – The Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) has urged the MILF warns 5-year-old truce may government to settle the issue of ancestral domain to get the 11-year-old peace talks back to the negotiating collapse unless talks resume table. MANILA, Philippines — Muslim rebels warned Friday In a message on the MILF website, chief rebel that their five-year-old truce with the Philippine negotiator Muhaquer Iqbal and other MILF leaders government may collapse unless the two sides resume insinuated that the most pressing concern to get the peace stalled peace talks. talks “back on track” is how both sides would implement The talks broke off last year after the Moro Islamic all consensus points on ancestral domain. Liberation Front, which has been fighting for self-rule for Peace talks between the government and the MILF minority Muslims for decades, protested the government’s started Jan. -

Moalboal & Badian

Coastal Conservation and Education Foundation Sustainable Coasts, Involved Communities. 2019 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF 3 Executive Summary 4 Presidential Note 4 Message from the Executive Director EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 The Our Ocean Program 6 About CCEF 2019 has been a major milestone for the Coastal Conservaiton and Education Foundation in creating sustainable coasts and involving the communities in managing them. Among the highlights of this year’s activites 7 The Our Ocean Program are the Saving Philippine Reefs Expediion (SPR), Our Ocean Program, activities from Project ADABOSS and Project 8 Project SMILE ISDA and other collaborations with partners. This year’s Saving Philippine Reefs Epedition is composed of eight 12 Project SEAled International volunteers and 4 CCEF staff, who helped monitor the reefs in Moalboal and Badian. CONTENTS 16 Project SEAcured The main highlight of 2019 is the implementation of CCEF’s project called the “Our Ocean” Program, with its 20 Project ISDA three major projects, Project SMILE, in Barangay, Biasong Talisay, Project SEAledi in Siquijor and Project SEAcured 21 Project ADABOSS in Southeast Cebu muncipalities. 24 CCEF Highlights Project SMILE: Sustainable Mangrove program through Information, Linkages and Ecopreneurship 28 Saving Philippine Reefs Expedition The aim of Project SMILE is the development of a Sustainable Mangrove Program in Barangay Biasong, Talisay, Cebu, 2019: Moalboal & Badian Philippines by establishing Public-Private Partnership (PPP) with the local go]vernment of Talisay, the academe (i.e., 30 Collaboration with partners University of Visayas, local schools), the business sector and corporate partners to support mangrove protection 31 Securing the Coasts with CSR and management, environmental conservation, and ecopreneurship. -

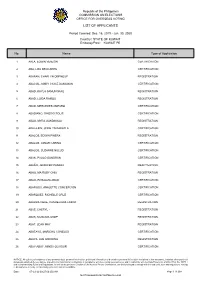

List of Applicants VRM 1

Republic of the Philippines COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS OFFICE FOR OVERSEAS VOTING LIST OF APPLICANTS Period Covered: Dec. 16, 2019 - Jun. 30, 2020 Country : STATE OF KUWAIT Embassy/Post : KUWAIT PE No. Name Type of Application 1 AALA, EDWIN VENZON CERTIFICATION 2 ABA, LIZA DEOCARES CERTIFICATION 3 ABABAN, CHARLYN OBENQUE REGISTRATION 4 ABACIAL, MARY CICILE BANAWAN CERTIFICATION 5 ABAD, KAYLA SAMUNGKAIL REGISTRATION 6 ABAD, LOIDA RAMOS REGISTRATION 7 ABAD, MERCEDES AMPARO CERTIFICATION 8 ABADIANO, SIRESIO SOLIS CERTIFICATION 9 ABAG, MYRA GANDAWALI REGISTRATION 10 ABALAJEN, JERALYN BABATLA CERTIFICATION 11 ABALOS, EDWIN PINERA REGISTRATION 12 ABALOS, JONAR CARINO CERTIFICATION 13 ABALOS, SUZANNE NULUD CERTIFICATION 14 ABAN, PAULO GUNDRAN CERTIFICATION 15 ABAÑO, JENNIFER PANDAY REACTIVATION 16 ABAO, MA RUBY CHIU REGISTRATION 17 ABAO, ROSALIZA ABAD CERTIFICATION 18 ABARGOS, ANALETTE CONCEPCION CERTIFICATION 19 ABARQUEZ, RICHELLE CRUZ CERTIFICATION 20 ABARRATIGUE, CANDELARIA LASCO REGISTRATION 21 ABAS, CHERYL - REGISTRATION 22 ABAS, MUSLIMA USOP REGISTRATION 23 ABAT, LEAH MAY REGISTRATION 24 ABATAYO, MARICHU CONEJOS CERTIFICATION 25 ABAYA, JOE ANN DINO REGISTRATION 26 ABAY-ABAY, MINDA OLAGUIR CERTIFICATION NOTICE: All authorized recipients of any personal data, personal information, privileged information and sensitive personal information contained in this document, including other pertinent documents attached thereto that are shared by the Commission on Elections in compliance with the existing laws and rules, and in conformity with the Data Privacy Act of 2012 ( R.A. No. 10173 ) and its implementing Rules and Regulations, as well as the pertinent Circulars of the National Privacy Commission, are similarly bound to comply with the said laws, rules and regulations, relating to data privacy, security, confidentiality, protection and accountability. -

Commission on Elections Certified List of Overseas Voters (Clov) (Landbased)

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS OFFICE FOR OVERSEAS VOTING CERTIFIED LIST OF OVERSEAS VOTERS (CLOV) (LANDBASED) Country : UNITED ARAB EMIRATES Post/Jurisdiction : ABU DHABI Source: Server Seq. No Voter's Name Registration Date 96571 SINAON, RIZA FERRER July 14, 2015 96572 SINAPAL, NORMINA ALI May 04, 2015 96573 SINAPILO, SUSAN BAUYON October 20, 2014 96574 SINAS, VERONICA TAN March 28, 2018 96575 SINAWILAN, SANDRO TYAGO August 12, 2015 96576 SINCER, VIVIAN DEFACTO October 29, 2015 96577 SINCERO, ANALYN METRAN January 15, 2015 96578 SINCIOCO, ARCHIE ABALUS July 01, 2014 96579 SINCIOCO, RODOLFO SR. RAMOS June 08, 2015 96580 SINCO, CHRISMA BRACEROS March 22, 2017 96581 SINCO, JENNELYN MARGES July 26, 2018 96582 SINCO, MA.TRECE BARROMETRO December 23, 2014 96583 SINCO, MARY JOY SOMBLINGO January 28, 2015 96584 SINCO, NENITA _ August 30, 2009 96585 SINCO, ROMANO BARAZON October 12, 2014 96586 SINCONIEGUE, EMMA PASA May 20, 2012 96587 SINCOSA, ALBERT NAZARENO February 08, 2015 96588 SINDAC, GILBERTO LEDESMA September 08, 2015 96589 SINDAC, JAY SALAZAR May 27, 2015 96590 SINDAC, RUEL FABRO July 07, 2009 96591 SINDAL, BIEN KARLO ENOY September 11, 2017 96592 SINDANUM, JUNBERT GERVACIO September 07, 2015 96593 SINDANUM, SHERYLL OCOMEN February 25, 2015 96594 SINDATOK, MARIAM GUIMALON March 05, 2015 96595 SINDATOK, NORHATA ARTILLAGA May 13, 2015 96596 SINDAY, LORNA CUTILLAR December 28, 2017 96597 SINDAY, MARJYRIE MIBOLOS December 17, 2014 96598 SINDAYEN, ELGEN DIZON June 13, 2017 96599 SINDAYEN, ROBERT DE LEON January 14, 2018 NOTICE: All authorized recipients of any personal data, personal information, privileged information and sensitive personal information contained in this document. -

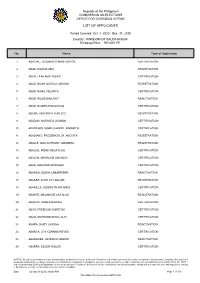

List of Applicants

Republic of the Philippines COMMISSION ON ELECTIONS OFFICE FOR OVERSEAS VOTING LIST OF APPLICANTS Period Covered: Oct. 1, 2020 - Dec. 31, 2020 Country : KINGDOM OF SAUDI ARABIA Embassy/Post : RIYADH PE No. Name Type of Application 1 ABACIAL, TEODERICO MAGTORTOR CERTIFICATION 2 ABAD, HALIMA ABO REGISTRATION 3 ABAD, LEAH MAE PONCE CERTIFICATION 4 ABAD, NOAH ANGELO VARGAS REGISTRATION 5 ABAD, RAMIL FELARCA CERTIFICATION 6 ABAD, ROSIE BALUYUT REACTIVATION 7 ABAD, SAMIRA PINAGAYAO CERTIFICATION 8 ABADA, VERONICA SUPLICO REGISTRATION 9 ABADAN, NORHATA GUIMAN CERTIFICATION 10 ABADEJOS, MORK GABRIEL ABOBOTO CERTIFICATION 11 ABADIANO, PRODENCIO JR. ANCHITA REGISTRATION 12 ABALLE, MAX ANTHONY OMAMBAC REGISTRATION 13 ABALOS, IRENE REGATCHO CERTIFICATION 14 ABALOS, MHARLON AMANCIO CERTIFICATION 15 ABAN, EDELDEN MORALES CERTIFICATION 16 ABANDO, ELENA CABARRIBAN REACTIVATION 17 ABANES, LOVE JOY DALIDA REGISTRATION 18 ABANILLA, JUDERLYN ARCENIO CERTIFICATION 19 ABANTE, MELANI DE LAS ALAS REGISTRATION 20 ABANTO, ARMER BARING CERTIFICATION 21 ABAO, FREEDOM GUIRITAN CERTIFICATION 22 ABAO, MOHAMMAD NUL ALIH CERTIFICATION 23 ABARA, DAISY LAGUNA REACTIVATION 24 ABARCA, JOY CZARINE REYES CERTIFICATION 25 ABARQUEZ, JOVENCIO ABDON REACTIVATION 26 ABARRA, EDLEN VIGUAS CERTIFICATION NOTICE: All authorized recipients of any personal data, personal information, privileged information and sensitive personal information contained in this document, including other pertinent documents attached thereto that are shared by the Commission on Elections in compliance with the existing laws and rules, and in conformity with the Data Privacy Act of 2012 ( R.A. No. 10173 ) and its implementing Rules and Regulations, as well as the pertinent Circulars of the National Privacy Commission, are similarly bound to comply with the said laws, rules and regulations, relating to data privacy, security, confidentiality, protection and accountability.